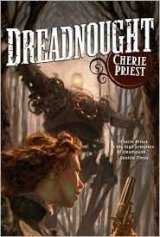

Текст книги "Dreadnought"

Автор книги: Cherie Priest

Соавторы: Cherie Priest

Жанр:

Стимпанк

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

She missed the last three ladder rungs and landed on the platform with a thud. Her knees ached, but her feet couldn’t feel the impact, as they were already deadened from the icy air and the freeze-and-refreeze of dampness.

“You!” she said, as if there were anyone else she might be talking to.

He gasped something in response, but it was unintelligible.

“Stay with me!” she commanded, and began the process of unbuckling the gunbelt from around her waist. It might work. Then again, it might not. The man alongside the train was a large fellow, brunet and heavyset but not so much fat as beefy. Regardless, he looked heavy.

Sending up a heartfelt prayer for the strength of the leather, she used the belt to lash herself to the platform rail-and she gave off a prayer for the railing, too. Then she ducked around the pole, held on tight with one still-ungloved hand, and held out the other one.

“Take my hand!”

He replied, “Mmmph!” as he tried to follow her instructions, flinging himself forward and grabbing, but she remained barely out of reach.

So she lowered herself, sliding down along the pole. She leaned like she’d never leaned before, stretching herself out as if she could gain a few inches in height by pure willpower. Her hand trailed farther from the gap, nearer to the man.

It wasn’t enough.

But all she had to do was let go with the hand that braced her. Let go of the rail. Gain that extra half a foot.

Yes.

“On the count of three!” she told him, since that was what worked for everyone else.

He nodded, and beads of sweat on his face went scattering as he jogged forward, still forward, almost spent-she could see it in his eyes.

“One . . . two . . . three!”

She released the pole and trusted the gunbelt to hold her, and the pole to hold the gunbelt, and the platform to hold the pole. She threw both arms out this time, leaning at her hips and straining. He gave one last surge-probably the last surge that was left in him-and closed the space between them.

Their hands met.

She seized his. He tried to seize back, but there wasn’t much strength for him to lend, so she did most of the work.

He stumbled.

She said, “God help me!” as she pulled him briefly off his feet. Then his knees were coming down against the tracks, and he was hanging in midair-supported just by her and the gunbelt. He was trying to help her help him, but it was hard, and he was almost gone, really. She’d asked too much of him, she could see that now; but she still had something of herself left, so she wrenched him up a joint at a time.

She had him by the wrists, and then the forearms.

Then the elbows.

Then the pole was beginning to bend and her arms were threatening to unhinge from their sockets, and the belt was straining as if the buckles might go at any minute.

The Rebel’s eyes went wide.

She knew what he was thinking, as plain as if it were written on his forehead. She growled, “No. Don’t. Don’t let go. Hang on.”

And then a pair of strong hands was on her shoulder, on both shoulders. Someone was pulling her up, and back, and drawing the Confederate with her.

She didn’t fight it, but pushed back into the utilitarian embrace. Soon the arms were around her waist, and then one was loose and reaching over her arms, to the Rebel, who took the hand that was offered him.

In a matter of moments, the three of them were on the platform. The Rebel, lying splayed there, threw up. Mercy, trussed to the bent pole, unbuckled herself with hands that shuddered with exhaustion. Inspector Galeano leaned against the wall of the car, holding his stomach and gasping.

“Thank you,” she told him.

The Rebel tried to say thank you as well, but instead threw up again.

Mercy asked, “You got the rest of them?”

He didn’t nod, but made a tired shrug and said between gulps of air, “Two of them. Another did not reach the train.”

The Rebel drew himself up to his quaking, bruised, scraped knees, and using the rail, pulled himself to his feet. He mustered a salute, and the inspector saluted back, parroting the unfamiliar gesture.

Mercy put a hand out and behind the Rebel, who might yet require a bit of steadying, in her professional opinion. But he held himself straight and wiped off his mouth with one sleeve, using the other to wipe his brow and cheeks as he followed the Mexican inspector into the passenger car.

They were greeted by Horatio Korman and Captain MacGruder, who were assisting the other two men who’d made it on board.

Lieutenant Hobbes was bent over one of the wounded Union men, offering comfort or bandaging. Mrs. Butterfield had stopped crying, and Miss Clay was still on point at the window nearby. Cole Byron stood by the forward doors, his dark skin shining with perspiration, and another porter crouched just beyond him, repairing a loosened connector. Morris Comstock was on his feet, and, like several of the other soldiers, was still picking off the undead here and there, though they could see fewer and fewer as the train gathered speed.

As the pace improved, the snow blew higher and harder around them, and this, too, helped wash the teeming undead away from the battered train and the passengers within it.

Everything was ice and soot, and gunpowder and snow, and a few dozen heartbeats spread along the train’s length. Most of the windows were gone, and the wind blew mercilessly inside, whipping hair into faces and clothing against bones.

For a while, no one spoke. Everyone was afraid to talk until the train was moving determinedly enough and the snowplow was kicking the debris high enough that not even the speediest of the monsters could catch them.

And then, after a few cleared throats, there were words of greeting.

Shortly thereafter, it was learned that Sergeant Elmer Pope, Private Steiner Monroe, and Corporal Warwick Cunningham were now in their midst, and all three men were exceedingly grateful for the assistance. They made no pretense of bluster. When things might have become awkward, given the circumstances, there instead came a moment of great camaraderie when the three Confederate men stood alongside the Union men and everyone looked out the windows at the retreating, ferocious, thinning hordes of the living dead.

The sergeant said, “I want you to know, we’d have done the same. Shoe being on the other foot, and all. Whether command liked it or not. We would’ve dealt with that later, but we wouldn’t have left you.”

And Captain MacGruder said, “I’d hope so.” He didn’t take his eyes away from the window until Inspector Galeano spoke.

As softly as the atmosphere would allow, the inspector said, “We’re all together in this.” Galeano was a ragged figure, his own uniform singed and seared with gunpowder, and bloodied here and there. His hat was missing and his wild, dark hair was more wild and dark than it should have been, but so was everyone else’s. They were northern and southern, Texan and Mexican, colored and white, officers and enlisted fellows . . . and, come to that, men and women. But the snow and the coal-smoke were finished with them now, and the wind had gotten its way. Their eyes were bloodshot and their faces were blanched tight with cold; and they were all bleak inside with the knowledge of something awful.

It was a train full of strangers, and they were all the same.

Inspector Galeano spoke again, and he was hoarse from the blizzard and the shouting. The Spanish consonants were filed sharp in his mouth. He said, “There will be questions. From everyone, everywhere. All our nations will want to know what happened here. And we are the only ones who can tell them.”

Captain MacGruder nodded. “There’ll be inquiries, that’s for damn sure.”

Sergeant Pope said, “We were after your gold, and you were after the Chinamen out West. We had a fight between us, fair as can be.”

“But we won’t get our Chinamen now,” said the lieutenant. “The deeds all went sucking out into the pass someplace when that crazy woman busted out the gold car’s window with a prybar.” He pointed at Theodora Clay, who stood utterly unapologetic. “And the gold . . . I don’t know. I expect there are better uses for it.”

Corporal Cunningham said, “And Lord knows we’re in no position to take it from you now.” He gave a rueful little smile.

“We both had our reasons,” said the captain. “Civilized reasons. Disagreements between men. But thosethings . . .”

“Those things” was repeated in muttering utterances around the car.

The Southern sergeant said, “I want all of y’all to know, we didn’t do that. Whatever was done to them . . . we didn’t do it. I’ve never seen anything like it in my life, and I don’t mind telling you, I near shit myself when they started eating my soldiers.”

“Us either,” said Lieutenant Hobbes.

And Captain MacGruder clarified, “They aren’t our work either. I’ll swear to it on my father’s grave.”

General murmurs of agreement and reinforcement made the rounds.

“As a representative of the government that once . . .” Inspector Galeano sought a word, and didn’t find it. So he tried again. “Those people-those things that aren’t people anymore-they were my countrymen. I can assure you that whatever became of them was no work of ours.”

The ranger said, “Nor Texas, and that’s a goddamned fact.”

Anyone could’ve argued, but nobody did.

But everyone’s innocence having been established, a great round of speculation got under way. If not the North, and if not the South, and if not Texas or Mexico . . . then who? Or, God help them all, what if it were a disease-and there was no one at fault, and no one they could demand an explanation from?

All the way to Salt Lake City, the passengers and crew of the Dreadnoughthuddled and whispered, periodically checking themselves in the lavatories for any signs of drying eyes, graying skin, or yellowing membranes.

And no one found any.

So Mercy told them everything she knew about the yellow sap, and Inspector Galeano told them about a northwestern dirigible that had crashed in West Tejas,carrying a load of poisonous gas.

Twenty-one

The next morning, the Dreadnoughtpulled what was left of its cargo and passengers into the station at Salt Lake City. Everyone on board looked and smelled like a war refugee.

All the occupants, including the conductor, his crew, and all the porters, stumbled down from the metal steps and onto terra firma in the Utah territory with a sense of relief that prompted several of the remaining civilians to burst into tears. Chilled beyond the bone, with many of them sporting injuries large and small that Mercy had done her best to patch, everyone was dazed. The train’s boilers cooled and clacked, but its hydrogen valves were all tightened into silence. Its interior was littered with broken glass, bullet casings, and blood. There it sat on the line, abandoned and silent, a husk that-for all its mighty power-looked forlorn.

Mercy sat on a bench inside the station’s great hall with Ranger Korman, Inspector Galeano, and the three Rebel soldiers. All in a row they watched the people bustle by, coming and going, taking notes and asking the inevitable questions.

Though they received a few strange glances, no one stopped them to ask why three Confederates had been aboard or why they were being permitted to simply leave;and no one demanded to know what a Mexican inspector was doing there; and no one wondered aloud why a Texas Ranger was this far north and west of his home turf.

This was not America, after all. Nor the Confederacy, or Texas, or Mexico either. So if anybody cared, nobody said anything. There was no war here, Utah’s or anybody else’s.

Paperwork was sorted.

New trains were offered.

All the rattled civilians were sent to their original destinations.

Theodora Clay and her aunt Norene vanished without a good-bye. Mercy wondered if Horatio Korman ever got his gun back, but she didn’t ask. She was pretty sure that if he’d wanted it, he would’ve seen about retrieving it. Captain MacGruder and Lieutenant Hobbes were assigned to another train and other duties before Mercy ever got a chance to tell them how much she’d appreciated their presence. But she liked to think they knew, and understood.

In time, someone approached the three southern men and gave them envelopes with tickets, back east and south, Mercy assumed. The soldiers offered quiet parting salutations and tips of their hats and were gone. Inspector Galeano left next, taking his tickets and claiming his seat on a train that would eventually take him to his homeland, where he would have a most amazing story to tell.

Then it was the ranger’s turn. Horatio Korman stood, touched the rim of his hat, and said, “Ma’am.” And that was all.

He, too, left her seated on the wide wooden bench, all alone and not quite certain if she was glad for the sudden privacy after so many weeks of being cooped up and crowded . . . or if she was very, very lonely.

But finally it was her turn, and the conductor of her own train was crying, “All aboard!” on the tracks outside. She squeezed her tickets, climbed to her feet, and met her train.

It was called the Rose Marie,and it looked nothing like the Dreadnought,which was somehow both reassuring and disappointing. By comparison, the Rose Marielooked like a fragile thing, something that could not possibly make the remainder of the journey-over mountains or around them, across plains and along rivers, for another thousand miles.

But the little engine with its pristine sleeper cars and shiny steel trim carried her swiftly-at times even more swiftly than the Dreadnoughtever did, which was no surprise, since its load was lighter and it was not dragged down with a militia’s fortune in arms and ammunition.

The rest of the mountain chain passed with a panorama of epic scenery sometimes covered in snow, and sometimes glittering with sky blue lakes of melted ice.

Mercy did not talk to her fellow passengers much. What would she say?

Beyond the most necessary pleasantries, she ignored and avoided them, and she was likewise ignored and avoided. Even though she’d cleaned her cloak and dress to the best of her abilities, they still showed bloodstains and tears, and-as she discovered in the washroom one morning-two bullet holes. Her hands were bandaged, a task she’d undertaken by herself and upon which she’d performed a decent job, if not a great one; but her fingers ached all the time as they healed, and the new skin stretched tight and itchy across the places where she’d lost the old.

The last thousand miles, between Salt Lake City and Tacoma, were exactly as uneventful as the first two thousand had been action filled.

Sometimes, when she thought she’d go stark raving mad with boredom, she’d remember lying atop the roof of the Dreadnought’s passenger car, the skin of her throat sticking to the freezing metal and her hands all but glued together by ice. She’d recall watching the southern soldiers as they ran, dodging, ducking, between the ranks of the hungry dead, running for their lives. And she imagined the smoke and snow in her hair, and then she considered picking up a penny dreadful or two at the next stop.

She picked up a total of three, using almost the very last of her cash.

She even read them. Well, she had the time. And nothing else to do.

And people tended not to bother a woman with a book.

After a few days, she checked the newspapers at every stop, looking for some sign that someone-anyone-had made it back and begun to explain what had happened at Provo . . . and the Dreadnought,and the people who’d ridden upon it. But she never spied any mention of any of these things, so she told herself that it must be too soon. Inspector Galeano could’ve never made it back to Mexico yet; Ranger Korman wouldn’t have even hit Amarillo yet; and Captain MacGruder wouldn’t be back at the Mississippi River yet. So she’d be patient, and wait. Eventually, the world would know. Eventually, a newspaper somewhere would have to announce the story and tell it whole, and true.

Eventually.

But not while Mercy Swakhammer Lynch made her way to the West Coast.

In a dull fog of fatigue and apathy she rode through Twin Falls, Boise, and Pendleton. She spent the night in Walla Walla, and in the morning boarded another train, one called the City of Santa Fe. Then, on to Yakima, from whence she sent her final telegram to her final destination, in hopes that the sheriff would be there to collect her, because if he wasn’t, Mercy had no earthly idea what she’d do next.

Cedar Falls. Kanaskat.

Auburn. Federal Way.

Tacoma.

Mercy exited the train with an upset stomach and a nervous headache.

She stepped into an afternoon covered with low gray clouds, but the world felt bright compared to the relative shade of the train’s interiors. It was cold, but not exceptionally so. The air was humid and tasted strange-a little tangy, and a little sour with a scent she couldn’t quite place.

The station was a big compound, but the tracks were not very crowded, and the City of Santa Fewas the only train debarking. Only a few people milled around the station’s edges-the station managers, the engineers, the railmen who worked the water pumps and inspected the valve connections, and the ubiquitous porters . . . though she noticed that they weren’t all black. Some were Oriental, in the same sharp porter uniforms but with hair that was long and braided, and sometimes shaved back from their faces.

Mercy tried not to stare, but the sight of so many at once amazed and distracted her.

Her curiosity about the men did not distract her from the unsettling truth of her situation. She was three thousand miles from home, absolutely broke, and possessing virtually nothing but the clothes on her back and the contents of her medical satchel, which had become much depleted over the weeks.

She stood beside the station agent’s door and tried not to fret about the circumstances. She scanned the face and vest of every passing man, hoping to spot a badge or some other mark that would identify a sheriff.

So she was rather unprepared to hear, “Vinita Swakhammer?” Because in order to reply, she was compelled to address a smallish woman in her mid-to late thirties. This smallish woman wore pants that were tucked into the tops of her boots and a fitted waistcoat with a badge clipped to the watch pocket. Her jacket was frankly too large, and her brown slouch hat was held aloft by a curly tangle of dark brown hair that was streaked with orange the shade of cheap gold.

“Sh . . . ,” Mercy began. She gave it another shot. “Sheriff-?”

“Briar Wilkes,” the other woman said. She stuck out her hand.

“And you’re . . . you’re the sheriff?”

She shrugged. “If there’s law in Seattle, I guess it’s me as much as anybody.”

“I never heard of a woman sheriff before.”

“Well, now you have,” Briar said, but she didn’t seem to take any offense.

Mercy imagined it was the sort of thing she answered questions about all the time. She said, “I suppose so. I didn’t mean to be rude.”

“Don’t worry about it. Anyway, do you have any . . . bags or anything?”

“No. This is it,” Mercy said. Then she asked quickly, “How did you know it was me?”

Briar Wilkes cocked her head toward the station’s exit and led the way out. “For starters, you were the most lost-looking person on the landing. You must’ve had a real long trip, coming all the way from Virginia. You ever been out this far west?”

“No ma’am,” she said. “First time.”

“That’s what I figured. And anyway, you’re about the right age, and traveling alone. I didn’t know you were a nurse, though. That’s what the cross on your bag means, right?”

“Right. I worked in a hospital in Richmond.”

The sheriff’s interest was piqued. “Smack in the middle of the war, huh?”

“Yes ma’am. Smack in the middle.”

“That must have been . . . hard.” Sheriff Wilkes led the way back outside, which put them in front of the enormous building. “We’re going over there, just so you know.” She pointed down the street, where a set of docks were playing host to a small multitude of airships. “I hope you don’t have any trouble flying. I know some folks are afraid of it.”

“That’ll be fine. How far away is Seattle from here?”

“Oh, not far. It’s maybe thirty miles to where we’re going. And I can’t believe I didn’t think to tell you right away, but your pa’s doing all right. For a while there, we really thought he wasn’t going to make it, but he pulled through.”

“Really?” said Mercy, who likewise couldn’t believe she hadn’t thought to ask. It was the whole point of her trip, wasn’t it, finding her father, and seeing him?

Sheriff Wilkes nodded. “Really. He’s just about the toughest son of a gun I ever did know. Or he’s in the running for that title, that’s for damn sure. I say that, because you’re about to meet one of the other toughest sons of a gun I know. You see that dirigible right there?”

She indicated a patchwork metal monster that bobbed lazily above a pipe dock.

Mercy could see the top of it, but not much of the bottom. That bit was blocked out by the dockyard gate, and another, smaller ship. “I see it.”

“That’s the Naamah Darling. Her captain, Andan Cly, is a friend of mine and your daddy’s.”

“I didn’t know my daddy had any friends,” she said, then caught herself. “I mean . . . Oh hell, I don’t know what I mean. I haven’t seen him, you know? Not in years. Not since I was a little girl.”

Briar Wilkes said, “That’s what he told me, and he feels real bad about it. Worse probably than he’s willing to say. But when he thought he was dying, and we didn’t know how much longer we could keep him alive, the one thing he kept asking for, over and over, was to see his little girl.” She gave an ironic laugh. “Course, he was delirious as could be, and I finally figured out that his little girl had to be a grown woman now. And it took us a while to get enough details out of him to track you down. I won’t lie to you, it was a pain in the ass.”

“I bet.”

“We sent out word with air captains in every direction, especially those who went pirating along the cracker lines, or who had connections back East. He said last he knew of you, you’d been in some town called Waterford.”

“That’s right,” she said.

“But we couldn’t find it, and could hardly find anyone who’d heard of it. But one of Crog’s old buddies-Crog, he’s . . . he’s another one of the air captains out here, one of Captain Cly’s good friends-anyway, Crog’s buddy said it wasn’t too awful far from Richmond.” She caught herself, or caught Mercy looking overwhelmed and uncertain. So she changed direction and said, “But I won’t bore you with the details. Suffice it to say, it took some doing, tracking you down.”

“Well, it took some doing, getting myself out here,” she said softly.

It was Sheriff Wilkes’s turn to say, “I bet.”

They walked in silence for the rest of the block, until they reached the gates. Then the sheriff paused and turned to her charge. “Listen, there are some things I ought to tell you, before we get to Seattle.”

Mercy got the distinct impression that Briar Wilkes was going to continue right then and there, on the very spot, telling her whatever things she had to say, but someone hailed her from over by the pipe docks.

“Wilkes!”

“I’m coming, I’m coming. Keep your shirt on, Captain.”

Rather than declare further impatience, the speaker emerged from underneath the Naamah Darling,stepping slowly into the wide gravel aisle next to his ship. The captain-for this surely must be him-looked up and down at Mercy and said, “So this is Jeremiah’s girl?”

“Sure is,” said the sheriff.

“Damn sight prettier than her old man, I’ll give her that,” he said with a crooked grin that was surely meant to be disarming.

Mercy didn’t realize for a moment that she’d stopped in her tracks upon catching sight of Captain Cly. And then she understood his attempt to disarm, and why he seemed to move carefully, as if he thought he might frighten her.

She was staring at the single largest man she’d seen in all her life.

And Mercy Lynch had seen plenty of men in her time-soldiers, big fighting lads, strapping old boxers and wrestlers, blacksmiths and rail-yard workers with shoulders like sides of beef. But she’d never seen anyone who was quite the sheer sizeof Andan Cly, captain of the Naamah Darling. Seven feet and change, surely, the captain hulked in the center of the lane, holding still and keeping that crooked smile firmly in place, though now he was aiming it at the sheriff. He was an awesomely constructed fellow, with rippling arms and a long torso that boasted muscles like railroad ties under snow, showing through his thin undershirt. The captain was not particularly good-looking-he was bald as an apple with jutting ears-but his face wore lines of sharp intelligence and his eyes hinted at a warmth that might be friendly.

She thought he must be chilly, running around like that, but he didn’t look cold. Maybe he was so big that the cold couldn’t touch him.

Mercy Lynch gave his cautious smile a tentative return, and followed Briar Wilkes up to greet him. She shook his hand when he offered it to her, and she said, “It’s nice to meet you.”

“Likewise, I’m sure. I hope you had a pleasant trip.”

She opened her mouth to reply, but didn’t know what to say. So she closed it again, then responded, “It was an adventure. I’ll tell you about it on the way, if you want.”

“Can’t wait to hear it,” he said, and he scratched at the back of his neck-a nervous gesture, one that was holding something back. “But while we’re flying, I think we probably ought to tell you a few things about Seattle-before you see it for yourself, I mean. I expect Briar here told you about your father-that he’s doing okay after all?”

“She told me,” Mercy said.

He nodded, and quit scratching at his neck. “Right, right. But I don’t guess she got around to telling you about . . . wherehe lives?”

“It hadn’t come up yet,” the nurse responded.

“I was working my way to it,” Briar Wilkes said.

Mercy was forced to wonder, “Is it . . . is he . . . is it bad? Is there something wrong, like he’s in a jail, or a poorhouse, or something?”

The sheriff shook her head. “Oh no. Nothing like that. For what it’s worth, we live in the same place. Me and my son, we live in the same building as your dad. It’s just . . . well, see . . . it’s just . . .”

The captain took over. “Why don’t you come on up inside, and we’ll give you the whole story, all right?” He put a hand on her shoulder and guided her toward the ship. “It’s a longstory, but we’ll try to keep it short. And there’s no shame on your dad in any of it. We just have a peculiar situation, is all.”

Beneath the Naamah Darlingwas a set of retractable stairs not altogether different from the ones that led up into a train’s passenger car, but longer by two or three measures. She followed the sheriff up inside the belly of the airship. The captain brought up the rear, drawing the steps behind himself and shutting them all inside.

The ship’s cockpit was all rounded edges and levers, all buttons and steering columns and switches in a curved display with three seats bolted into place. The center seat was oversized and vacant, marking it as the captain’s chair. The other two were occupied, and both swiveled so their occupants could see the newcomer.

In the left seat was a slender Oriental man about twenty-five or thirty years old. He wore a loose-fitting shirt over ordinary pants and boots, and a pair of aviator’s goggles was pushed up onto his bare forehead.

The captain pointed one long finger at him and said, “That’s Fang. He understands you just fine, but he doesn’t talk. Right now he’s pulling double duty as first mate and engineer.”

To which the occupant of the other chair said, “Hey!” in a tone of half-joking objection. The objector was a teenager still, and skinny as a rail with brown hair that hosted a nest of cowlicks.

Andan Cly pointed at him next, saying, “That’s Zeke, and . . . and where’s Houjin?”

An equally young head popped out of the storage bay at the rear of the craft. “Over here.” The head vanished.

“Over there, yeah. Of course he is. Anyway, that’s Zeke, like I said, and the other one’s Houjin-sometimes called Huey, sometimes not.”

Briar Wilkes pointed at the boy in the third seat and said, “Zeke’s my son. Huey”-she cocked her head toward the place where Huey had briefly appeared-“is his buddy. I guess they think they’re going to see the world together or something, if they can talk the captain into teaching them how to fly.”

The captain made a grumbling noise, but he didn’t put much weight behind it. “They’re both sharp enough, when they pay attention,” he said. It wasn’t high praise, but it made Zeke beam, and it brought Huey up out of the cargo bay.

The Oriental boy was Zeke’s age and approximate size. He had a keen, smart face and a long top braid like Fang’s, but he was dressed almost identically to Zeke, as if the two of them had coordinated this semblance of a uniform, and were determined to play at being crew.

The captain said, “All right, everyone. You’ve had your chance to stare. This here is Jeremiah’s girl, Miss Vinita Swakhammer.”

Mercy said, “Hello, um, everyone. And just so you know, I’m . . . well, I wasmarried, so it’s Vinita Lynch. But y’all can call me Mercy if you like. It’s just a nickname, but it’s stuck.” Before anyone could ask, she added quickly, “My husband died. That’s why I’m out here alone.”

Andan Cly said, “I’m real sorry to hear that, ma’am,” and the sheriff mumbled something similar.

Standing in the center of the bridge, she felt large and awkward in their midst; and now they felt sorry for her, which made her feel even more conspicuous. She was taller and heavier than everyone present except for the gigantic captain, and her summer coloring stood out against the dark hair and eyes of everyone else. Unaccustomed to feeling quite so out of place, and a little uncomfortable at being the object of everyone’s attention, she nonetheless continued, “Well. Thanks a whole bunch for picking me up and giving me a ride out to my daddy. I appreciate it.”

Briar Wilkes assured her, “We’re happy to do it. And now that the captain’s finally welded in some extra seating, we’ve even got the space to transport you without making you sit on the floor.”