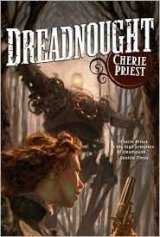

Текст книги "Dreadnought"

Автор книги: Cherie Priest

Соавторы: Cherie Priest

Жанр:

Стимпанк

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Nine

Though Mercy had been warned of the possibility of motion sickness, she did not become ill and was thankful for it. The food was fairly good, the weather remained quite fair-sunny and cool, with the ever-present breeze off the river-and the voyage promised to be pleasant and problem free.

However, by the second day, Mercy was bored beyond belief. It wasn’t quite like being bored on a train. Despite the fact that she could get up, and wander through several decks, and lie down or stretch her legs at her leisure, something about being in the middle of that immense, muddy strip of water made her feel trapped in a way that a simple railcar did not. Certainly, it would be easier to dive overboard and swim to safety should trouble present itself than to fling herself from a moving train; and to be sure, the grub down in the galley was better than anything she’d ever packed for herself; and it was a demonstrable fact that this boat was making swifter progress than virtually any of the others it passed going upriver. But even when the paddles were churning and the diesel was pumping so fast and hard that the whole craft shuddered, she couldn’t shake the sensation that they were moving more slowly than they ought to be.

The captain told her it was a trick of the water, and how swiftly it worked against them. She forced herself to be patient.

If the sun was out, she’d sit on the benches on the deck and watch the water, the distant shore, and the other vessels that moved along beside them, coming and going in each direction, up and down the river. Bigger, heavier cargo fleets swam along at a snail’s crawl, paddling and sometimes towing barges packed with cotton bales, shipping crates, and timber. Lighter, prettier steamers from the Anchor Line piped up and down, playing their organs alongside the whistles to announce themselves and entertain their passengers. Every now and again, a warship would skulk past, the only kind of craft that could outpace the Providenceas she surged forward into the current. On their decks Mercy saw grim-faced sailors-and sometimes happy ones-waving cloths or flags at the Texian vessel, waiting for the captain to pull the chain and sound his whistle back at them, as he invariably did.

The warships made her think of Tennessee, and of Fort Chattanooga, and that terrible night near Cleveland. They also reminded her of the newspaper she’d stashed in her satchel, so she retrieved it and sat outside reading it while the weather and the light held.

As she read, scanning the articles for interesting highlights, then reading the whole things anyway, she was joined on the bench by Farragut Cunningham, a Texian cargo manager with a shipment of sugar from the Caribbean. He was a great friend of the captain’s, and had swiftly become a reasonable and engaging conversation-mate. Mercy was terribly interested in the extensive traveling he’d done for his business dealings, and on their first night aboard she’d interrogated him about the islands. She’d never been on an island, and the thought of it fascinated and charmed her.

On the second day of the journey, he sat beside her on the deck bench and struck a match. He stuck it down into the bowl of his pipe and sucked the tobacco alight with a series of quick puffs that made his cheeks snap.

“Is any of the news fit to read?” he asked, biting the end of the pipe between his teeth so that it cocked out of his mouth at an angle, underneath the fringe of his dark brown mustache and just to the right of his chin, where a red streak bisected his beard.

“Some of it, I guess,” she replied. “It’s a couple days old now, but I don’t have anything else to read.”

“No paperbacks? No novels, or assortments of poetry?”

She said, “Nope. I don’t read much. Just newspapers, sometimes, when I can get my hands on ’em. I’d rather know what’s happening than listen to someone tell me a story they made up.”

“That’s a reasonable attitude to take, though it’s a shame. Many wonderful stories have been made up and written down.”

“I guess.” She pointed at the article about the Dreadnought’s movement out of southern Tennessee, and she said, “I almost saw that thing, the other night.”

“The Dreadnought?”

“That’s right. I was taking an airship from Richmond to Chattanooga, and we crashed down right in the middle of the lines, just about. That engine was there, and everyone acted like they was scared to death of it.”

He took another puff, filling the air with a dim, sweet cloud of grayish blue smoke. “It’s a frightful machine, and I mean that in more ways than one.” He lifted the brim of his hat and scratched a spot on his hairline while staring out into the distance, over the water.

“How so?”

“On the one hand, it’s a machine built to be as mighty and dangerous as possible. It’s armored to the teeth, or from the cowcatcher to the hitch, however you’d like to look at it. It’s a dual-fuel creature like this ship-part diesel and part coal for steam-and it can generate more power than any other engine I ever heard of. It’s plenty fast for something as heavy as it is, too.” He added softly, “Faster than any other engine the Union’s got, that’s for damn sure, armored or not.”

“But not faster than ours?” She didn’t bother to differentiate between the Confederacy and the Republic. She’d learned already that aboard this ship the distinction was merely semantic.

“No, not faster than ours. Course, none of ours are half so deadly. We could catch the Dreadnought,no problem at all. But God knows what we’d do with it, once we caught it.”

Mercy looked back down at the sheet, spread across her lap. “What about the other hand?”

“Beg your pardon?”

“You said ‘on the one hand.’ What’s on the other one?”

“Oh. That’s right. On the one hand, the engine is frightful because it’s an instrument of war. On the other hand, it was designed quite deliberately to make people afraid. You said you were there, in Tennessee,” he cocked his head at the paper. “Did you get a good look at it?”

“No sir, I didn’t. I only heard the whistle, back on the battlefield. I heard it brought a Union mechanized walker to the fight.”

He said, “I reckon it did. Those walkers weigh so much, there’s no other way to move ’em around the map. All powered up, even our petroleum-powered walkers can’t run more than an hour or two. The Yanks have those shitty steam-powered jobs. They can hit like the dickens-don’t misunderstand me-but no one can stand to drive ’em for more than thirty minutes. But now, you said you didn’t see the Dreadnought.”

“No sir. You ever see it?”

He nodded. “I saw it once, up in Chicago when I was passing through on my way to Canada to nab a load of pelts. I saw it in the train yard, and I don’t mind telling you, it made me look twice. It’s a devil of a thing. It’s got so much plating that it looks like it’s wearing a mask, and they’ve welded so many guns and light cannon on top of it, it’s a wonder the damn thing’ll roll at all; but it does. If you came that close to it and never saw it, much less encountered it up close and personal, that’s a lucky thing for you,” he said. Then he amended the assessment to include, “Airship crash or none.”

He sucked at the pipe for a few seconds. Mercy didn’t say anything until he pulled the pipe out of his mouth and used it to point at the bottom right of the page. “Now, what’s that say? Down there? Can you tell me?”

“Something about Mexico, and the emperor there being up to no good.”

Farragut Cunningham snorted. “Well, that just makes it a day ending with a y. Can you read me a line or two? I left my magnifiers in my cabin, and I can’t hardly see a thing without them.”

“ ‘Emperor Maximilian the Third accuses Texian vigilantes, rangers, and residents in the mysterious disappearance of Mexican humanitarian legion.’ ”

The Texian sniffed. “I just bethe does.”

She went on. “ ‘The emperor insists that the troops were merely a peacekeeping force sent north in order to assist the emigration of Mexican nationals back into undisputed Mexican territory-’ ”

“Let ’em go. Let ’em all go, we don’t want ’em.”

“ ‘Texians have disputed that claim, and insisted that the military presence amounted to an act of invasion.’ ”

“More or less, damn straight that’s what it is. Should’ve never sent those uniforms over the Rio Grande like that-they sure as hell know that’s their boundary, agreed upon by their own people, and years ago now.”

Mercy looked up from the paper. “All right, I’m confused. Does this mean there are Mexicans in north Texas?”

Her bench-mate fidgeted as if this was an irritating subject, and stuffed the pipe back in his mouth. “Oh, you know how it is. They done lost their war, and now the nation’s ours. But they like to dicker with us about where the northwest lines are.”

“That seems . . . imprecise.”

“Maybe it is, a little. Problem is, even when we can agree with ol’ Max on where the northwest boundaries are, the people who live there sometimes don’t. I ain’t going to lie to you-it’s the middle of godforsaken nowhere, and the homesteaders and settlers and the like, some of them are pretty sure they’re citizens of Mexico. But when the lines got redrawn-” He hesitated and clarified. “-when the lines got redrawn this most recenttime, a bunch of citizens got right peeved about paying taxes to the Republic, when they thought they were Mexicans.”

“So now Mexico is helping them . . . move back to Mexico? Even though they already lived in Mexico, as far as they knew?” she asked.

“More or less. But things change, and the map lines change, and people can either go with that flow or go jump, for all I care.”

Mercy glanced down and skimmed the rest as quickly as she could. “Then why’d Texas get upset, if the troops were only there to move their own folks back to the right side of their line?”

Cunningham sat forward and used the pipe to gesture like a schoolteacher, or like someone’s father explaining the family’s political opinion to a child with too many questions. “See, if that’s allthey were doing, that’d be fine. But if all they wanted was to move their own folks back, they didn’t have to send five hundred men with guns and uniforms, bullying their way up past Oneida. They could’ve just sent some of their religious folk from the missions or something-since they got papists coming out the ears-or maybe they could’ve talked to that Red Cross. Get some people out to help the relocaters relocate, that’s fine; but don’t send the contents of a presidio and expect everybody to believe they’re minding nobody’s business but their own.”

Mercy nodded, even though there was a lot she didn’t really understand. She followed enough to ask, “What happened to the troops, then? Five hundred men don’t just disappear into thin air.”

He leaned back again, still drawing shapes with his pipe, which was nearly burned down cool. “I don’t know if it was five hundred or not. Something like that, though. And I don’t know what happened to ’em-could’ve been anything. That far north and west, shoot . . . could’ve been rattlesnakes or Indians, or cholera, or a twister . . . or maybe they ran across a town big enough to object to a full-on military garrison sneaking across their property. I’m not saying they ran afoul of the locals, but I’m saying it could’ve happened, and it wouldn’t surprise me none.” He put the end of the pipe back in his mouth and bit at it, but didn’t suck at it. And he said, “Wouldn’t be nobody’s fault but their own, neither.”

“I’m sure you’re right,” Mercy said, despite the fact that she wasn’t. But she didn’t want to be rude, and there were lots of things she didn’t know about Texas-and even more she didn’t know about Mexico-so she wouldn’t open her mouth just to put her foot in it.

“You see anything else interesting in that paper?” Cunningham asked, giving up on the pipe and drawing one leg up over his knee so he could tamp out the bowl’s contents against the heel of his boot.

“Most of the rest of it’s just stuff about the war.”

“No big surprise there, I guess. Does it say anything about what the Yankees were doing, pushing that line down all the way past Nashville? They must’ve had somegood reason for a spearhead like that. God knows they went to plenty of trouble to make it happen, bringing that engine and that mech. Then again,” he mused, “maybe there’s no good reason. Maybe we’re just whittling the war down to the end, and this latest back-and-forth is only its death throes. It feels like the end. It feels like something thrashing about before it’s done for.”

Mercy said, “Naw, it don’t talk about why; it just talks about them doing it.” She folded the paper over again, halfway rolling it up. She offered it to the Texian, asking, “Would you like it? I’ve read it now, top to bottom and front to back, and I’m done with it.”

“Thank you, ma’am, but no thank you. Looks like more bad and pointless news to me. I’d just as soon skip it.”

“All right. I’ll just put it in the game room, on one of the poker tables.” She rose, and Cunningham rose with her, touching the front of his hat.

He then sat back down and refilled his pipe. Once it was alight again, he leaned back into the bench to watch the river, the boats, and the occasional fish, turtles, and driftwood sweep on past.

Ten

Supper came and went, what felt like many times over, and the days ran together as the Providencedragged itself upstream. It sometimes docked at little spots and big spots between the big cities, loading and unloading cargo, and every now and again losing one or two passengers and taking on one or two new ones. At the Festus stop, the Providencepicked up another Texian, as if to maintain some balance of them. The nurse was beginning to think they must be as common as brown, to encounter them just about everywhere.

The new Texian was Horatio Korman, and he was polite without being effusive, preferring to keep to himself for the short remainder of the trip. He was of a somewhat indeterminate age (Mercy guessed he might be thirty-five or forty, but with some faces it was difficult to judge, and his was one of them), with an average height and build, uncommonly green eyes, and hair that was quite dark, except where a faint streak of white went tearing along the part. His mustache was a marvel of fluff, each wing as big as a sparrow, and clean but not excessively groomed. Mercy thought he looked rather pleasantly like a Texian on an advertisement she’d once seen for a brand of chewing tobacco, as if he fit some mold that she’d heard about, but never actually encountered.

He came aboard with two handheld luggage cases that appeared to be heavy, even for a man with long, apelike arms such as his; and she noted the enormous pair of guns he wore openly on his belt. They were bigger than her inherited six-shooters by another third, and they hung off his hips like anchors. A long, slim spyglass stuck out of one vest pocket and gleamed a little when he walked.

Captain Greeley saw Mercy watching the new Texian board and find his way to a room. He told her, “That Horatio. He’s a real piece of work, as they say.”

“How’s that?”

The captain shrugged, and lowered his voice just enough to ensure that everyone on deck would listen closely. “You may as well know: He’s a Ranger of the Republic.”

“That’s some kind of lawman, right?”

“That’s right.” He nodded. “I’ve known Ratio going on ten years now, and I’m glad to have him aboard. Not that the going’s been rough, because it surely hasn’t been. It’s been a smooth ride, wouldn’t you say, Mrs. Lynch?”

She said, “Yes sir.”

“But sometimes the trips aren’t so easygoing; and sometimes, the passengers aren’t so easygoing either. I don’t mind telling you, I think that having a woman on board might’ve had a . . . a civilizingeffect on some of the lads.”

“Now don’t you go blaming a boring river run on me,” she said.

“Wouldn’t dream of it! But it’s a given: without you there’d have been more drinking, more fussing, and more cardplaying . . . which means more fighting, almost definitely. I know you’re leaving next stop, and I won’t hold that against you, but I hope Horatio stays aboard awhile. He’ll keep me out of trouble. I’d hate to go to jail for throwing a fellow overboard-whether he deserved it or not. I’d rather leave that to the ranger.”

The last night’s supper was a good one, and the next day’s trip was as uneventful as the previous week. When the Providencepulled into St. Louis, Missouri, Mercy was itching to debark and pin down the next leg of her journey. The docking and the settling took half the morning, so by the time the boat was ready to let her go, she stayed one last meal to take advantage of the readily available lunch.

Finally she said her good-byes to the captain, and to Farragut Cunningham, and to Ranger Korman, who was cool but polite in return. She stepped out onto the pier and idly took the offered hand of a porter, who helped her to leave before he occupied the gangplank with the loading and unloading of whatever was coming and going from the boat.

Mercy dodged the dockhands, the porters, the sailors, the merchants, and the milling passengers at each stall as she left the commerce piers and went back onto the wood-plank walks of a proper street, where she then was compelled to dodge horses, carriages, and buggies.

She found a nook at a corner, a small eddy of traffic that let the comers and goers swirl past her. From this position of relative quiet, she pulled a piece of paper out of a pocket and examined it, trying to orient herself to Captain Greeley’s directions. A fishmonger saw her struggle to pick the right road, and he offered his services, which got her three streets closer to Market Street, but two streets yet away from it. She intercepted a passing soldier in his regimental grays, and he indicated another direction and a promise that she’d run right into the street she sought.

He was right. She ran right into it, then noted the street numbers on the businesses, which got her to the edge of a corner from whence she could actually spot the lovely new train station whose red-roofed peaks, towers, and turrets poked up over this corner of the city’s skyline. The closer Mercy drew, the more impressed she was with the pale castle of a building. Although the Memphis station had struck her as prettier, something about the St. Louis structure felt grander, or maybe more grandiosely whimsical. It lacked elaborate artwork and excessive gleam, but made up for it with classic lines that sketched out a medieval compound.

At one end of the platform, there was a crowd and a general commotion, which she skipped in favor of finding the station agent’s office. She followed the signs to an office and rapped lightly upon the open door. The man seated within looked up at her from under a green-tinted visor.

“Could I help you?” he asked.

She told him, “I certainly hope so, Mr.-” She glanced at the sign on his desk. “-Foote.”

“Please, come inside. Have a seat.” He gestured at one of the swiveling wooden chairs that faced his desk. “Just give me one moment, if you don’t mind.”

Mercy seated herself to the tune of her skirt’s rustling fabric and peered around the office, which was heavily stocked with the latest technological devices, including a type-writer, a shiny set of telegraph taps, and the buttons and levers that moved and changed the signs on the tracks that told the trains where to go and how they ought to proceed. Along the ceiling hung a variety of other signs, which were apparently stored there. STAY CLEAR OF PLATFORM EDGE read one, and another advertised that BOARDING PASSENGERS SHOULD KEEP TO THE RIGHT. Another one, mounted beside the door in such a way as to hint that it was not merely stored, but ought to be read, declared with a pointing arrow that a Western Union office was located in the next room over.

When Armistad Foote had finished his transcription, he turned to the telegraph key-a newfangled sideways number that tapped horizontally, instead of up and down-and sent a series of dots and dashes with such astonishing speed that Mercy wondered how anyone, anywhere, could’ve possibly understood it. When the transmission was concluded, the station agent finally pushed the device to the side and leaned forward on his elbows.

“And what can I do for you today?”

“My name is Mrs. Lynch. I don’t mean to interrupt your afternoon, but I’m about to take a real long trip. I figured you could tell me what the best way might be to head west.”

“And how far west do you mean to go, Mrs. Lynch?” He was a bright-eyed little man, wiry and precisely tailored in a striped shirt with a black cinch on his right sleeve. He smiled when he talked, a smile that was not completely cold, but was the professional smile of a man who spends his days answering easy questions for people whom he’d rather usher out of his office via catapult. Mercy recognized that smile. It was the same one she’d used on her patients at the Robertson Hospital.

She sat up as straight as she could manage and nodded for emphasis when she said, “All the way, Mr. Foote. I need to go all the way, to Tacoma.”

“Mercy sakes!” he exclaimed. “I do hope you’ll forgive me asking, Mrs. Lynch, but you don’t plan to undertake this trip alone, do you? May I inquire about your husband?”

“My husband is dead, Mr. Foote, and I absolutely dointend to undertake this trip alone-seeing as how I don’t have too many options in the matter. But I have money,” she said. She squeezed at the satchel as she added, “In gray and blue, what with this being a border state and all; and I brought a little gold, too-since I don’t know what’s accepted out past Missouri. It’s not a lot, but I think it’ll get me to Tacoma, and that’s where I need to go.”

He fidgeted, using his heels to kick his own swiveling seat to the left, and then to the right, pivoting at his waist without moving his torso or arms. He asked slowly, as if the question might be delicate, “And Mrs. Lynch, am I correct to assume-by the cadence of your voice, and your demeanor-that you’re a southern woman?”

“I don’t know what that’sgot to do with anything. Heading west ain’t like heading north or south, is it? But I’m from Virginia, if you really must know,” she said, trying to keep the crossness out of her voice.

“Virginia.” He turned the name over in his mouth, weighing what he knew of the place against the woman sitting before him. “A fine gray state, to be sure. Hmm . . . we have a train leaving very shortly-within the afternoon-for the western territories, with a final destination of Tacoma.”

She brightened. “That’s wonderful! Yes sir. That’s exactly what I’m looking for.”

“But there will be many stops along the way,” he cautioned as if this were some great surprise. “And the atmosphere might . . . prove . . .” He hunted for a word. “Unsympathetic.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“This is a place of contradictions. The train heading west is a Union train by origin, and most of its passengers and crew are likewise allied in sentiment-though you can be absolutely confident, this is a civilianoperation and in no way tied to the war effort at all. Not exactly.”

“Well, which is it? Not at all, or not exactly?”

He flipped his hands up as if to say some of each,and explained. “One of the last cars is transporting dead soldiers back to their homes of origin in Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, and the like. As far as I know, and as far as I can tell, that’s its sole official business, and they’re taking passengers along the route as a matter of convenience, and to offset the cost, of course.” He shrugged. “Money is money, and theirs is as good as ours. Suffice it to say, they have a refrigerated car full of valued cargo-the human cargo of slain veterans. I’m given to suspect that perhaps it holds a war hero or two, or maybe even General McDowell, whose widow and family have moved out to California. Though the caskets were sealed and unmarked, except by serial numbers, so I’m afraid I can neither confirm nor deny those suspicions.” But he smiled broadly, pleased to have guessed at a secret.

“Pretty much what you’re telling me is that the fastest, easiest-and you haven’t added cheapest, but I’ll trust you wouldn’t bring it up if it were unaffordable-way I can get myself West is to keep my head down and ride a Union wagon?”

“That’s the sum of it-yes. It’ll get you there, sure enough. Probably faster and safer than just about anything else we’ve got headed that way for the next month, truth be told.”

“And why’s that?” she asked.

He hemmed and hawed again, only momentarily. “There’s a bit of a military presence on board. The engine itself is of military vintage, and only the passenger cars are a civilian contribution.” His tone lifted into something more optimistic. “Which means that you can expect virtually no trouble at all from the Indians along the way, much less the pirates and highwaymen who trouble trains these days. It’ll be quite secure.” He stopped, and started again. “And anyway, what of it, if anyone somehow learns that you’re from Virginia? This is a civilian task, and a civilian train.”

Mercy wasn’t sure whom he was trying to convince. “You don’t have to sell me on it, Mr. Foote. My trip is likewise unrelated to the war effort. So I believe I’d like to buy a ticket,” she said firmly. “As long as the ride is safe and quiet, I’ll count my lucky stars that my timing worked out so good.”

“As you like, Mrs. Lynch,” he said, and he rose from his seat.

She let him make the arrangements, and finally, after she’d handed over almost the very last of her money, he gave her an envelope stuffed with papers, including her boarding pass and itinerary.

“The train’ll be boarding down at the end, at gate thirteen.” He pointed.

“Down where all those folks are stomping around, making a crowd?”

“That’s it. Now have a good day, Mrs. Lynch-and a safe trip as well.”

“Thank you, Mr. Foote.”

She stared out the window, down at the thirteenth platform. There wasn’t much to see there except for a dense and curious crowd, for the columns between her and the engine blocked the bulk of the view. Even through the obstacles, she could see that the engine was large and dark, as engines went, and an old warning thrummed in her head. Suddenly she knew . . . illogically, and against all sane rejection of undue coincidence . . . that once she got up closer, she’d recognize the machine, by reputation if not by sight.

She drifted dreamlike toward the crowd and then back to the edge of the platform, where the people moved more quickly and with less density. Following the thinner stream, she shifted her satchel to hug it more closely against her belly.

Blue uniformed men with guns pocked the scene, mostly staying close to the engine, to the spot that felt safest to them in this uncertain state of divided loyalties.

The engine’s stack rose into view first, between the platform beams that held the shelter aloft. It could’ve been any freight engine’s stack, dark and matte as wool made for mourning. The lamp-which also came into view as she drew nearer-could have been any lamp, rounded and elongated slightly, with a stiff wire mesh to protect the glass.

But then the pilot piece, the cowcatcher, eased into view as two men stepped apart. No longer could it be any engine, from any rail yard or nation. Devilishly long and sharp, the fluted crimson cage drew down to a knife’s bleeding, triangular edge, made to stab along a track and perform other vicious duties-that much was apparent from the rows of narrow cannon mounted up and down the slope against the engine’s face. In front of the pilot grille, even the rail guards that covered and protected the front wheels were spiked with low scoops and sharp points, just in case something small and deadly should be flung upon the tracks that the pilot might otherwise miss. All the way up the chassis more guns were nestled, as well as elaborate loading systems to feed ammunition to the devices in a Gatling style. And as she approached yet closer, squeezing her way through the crowd to get a look for herself, Mercy noted that the boiler was double-, or maybe even triple-plated, riddled with rows of bolts and rivets.

A water crane swung down low to hang over the engine. Soldiers ordered and shoved the onlookers back, demanding room for the crew and station workers to do their jobs; and soon the valves had been turned and the flow was under way. As the engine took on water for the trip ahead, spilling down the pipes into the still-warm tanks, the metal creaked and settled with a moan.

The gargantuan machine was nearly twice as large as the ordinary engine huddling two tracks over-not twice as wide, but longer, and somewhat taller, and appeared thicker and meaner in every way.

A man beside Mercy-some random gawker in the pressing crowd-turned to her as if he knew her and said, “My God, it’s enormous! It’ll barely fit under the station awnings!”

And behind her came a different voice, slightly familiar and heavily accented. “But it didfit,” said the speaker with great conciseness. The nurse turned around and saw the most recent Texian to come aboard the Providence-the Ranger Horatio Korman. He added, “You can bet they were careful about that,” and he tipped his Stetson to Mercy. “Mrs. Lynch.” He nodded.

“Hello,” she said, and moved aside, allowing him to scoot one booted foot closer to the tracks, almost to stand at her side. Together they stared ahead, unable to take their gazes away from it.

Along the engine’s side, Mercy could see a few of the letters in its name, though she could barely parse the sharp silver lettering with cruel edges and prickling corners that closely matched the gleaming silver trim on the machine’s towering capstack.

The ranger said it first. “ Dreadnought. God Almighty, I hoped I’d never see it for myself. But here I am,” he said with a sniff. He looked down at Mercy, and at her hand, which held the envelope with all her important papers and tickets. Then his gaze returned to the train. “And I’m going to ride whatever she’s pulling. You, too, ma’am?”