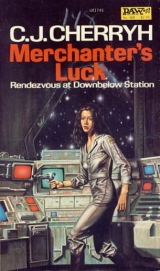

Текст книги "Merchanter's Luck "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Chapter VI

The customs seal was still in effect, Lucy’s access presenting deep shadow, a closed hatch where other ships had a cheerful yellow lighted access tube open. No lights here, only the customs barrier still in place, and grim dark metal of an idle gantry beyond —no cargo for Lucy, to be sure, but the abundant canisters of the ship in the next berth, which had been offloading, a busy whine of conveyers, a belt empty now, while they sorted out some snarl inside, perhaps. Native workers hovered about, idle… alien life, persistent reminder of possibilities. Man had found nothing else, but the quiet, avowedly gentle Downers of Pell,

It was perhaps out there, a star or two away. It might happen in his lifetime, some merchanter, disgruntled with things as they were, diverting his ship off to probe the deep… but the finding of nullpoints took probes, and probes took finance, and Lucy could never do it. Every route, everything that was settled in the Beyond rode that kind of maybe, that maybe this year… maybe someone… Sandor took some perverse comfort in that, that no one’s prerogatives were that secure.

This running gnawed at him. And it was rout, this time. He was a contamination, a hazard. He thought about Allison Reilly and knew it for the truth, the things she had said.

Maybe he should have taken the money. Or anything else he could get.

He walked along the line of canisters, saw nothing out of the way—Downers peered down at him from a perch atop the cans, suddenly scampered out of sight. He looked about him, walked the shadows closer and closer to the access. Lucy was not a large problem for customs, nothing that deserved as much fuss as his anxiety painted. Likely—he earnestly hoped—they had gotten some junior agent to suit up and walk through the holds to check out his claim that they were empty. The plates under which the gold was hidden were inconspicuous in hundreds of other like places, in the empty cavern of the badly lighted hold. They had looked, that was all, gone offshift—it was alterday.

He walked around the bending of the huge can-stacks, came face to face with blue uniformed militia, two grim-faced men. Blinked, caught off balance for the moment, then shrugged and strolled the other way, suddenly out of the notion to prowl about the customs barrier.

So. Too many troops, everywhere. Viking, and here. He shifted his shoulders, persuaded his frayed nerves to calm. Better to go to the offices, get it settled up there and not go try security out here. He walked lightly still, the more so when he had gotten the shock out of his system, tucked his hands into his pockets and looked about him as he walked, anonymous again, among the passing mobile sleds, the passersby that were mostly spacers or dock-workers—flinched once when a knot of stationers pointed at him and talked among themselves. But the mainday crowds were gone: the stationers who had seen his face on vid and gathered on the dock were decently in their beds, with the alterday shift awake. No one troubled him. He sealed off the experience back there, sealed off the nightmare of the docking, sealed off too the sleepover with Allison Reilly, getting himself focused again, sorting his wits into order. He might be on any station, at any year of his adult life. He had done the like over and over. His knees still felt like rubber, but that was hunger: he fished up the crushed sandwich out of his pocket—a prudent idea, that, after all; and that was his breakfast, dry, pocket-squelched mouthfuls while he walked the edge of the loading zones and headed for blue dock and the offices.

The combine had me carry the gold in case, sir—personal funds, no, sir, not transporting for general trade. He started composing his arguments in advance, against every eventuality they might haul up. The unsettled state of affairs, sir, the military—

No. Maybe not such a good idea to invoke that particular reason unless he had to. Unsettled state of affairs was close enough.

And with luck, they had not found the cache in the hold at all; with luck, he could pay his dock charges and get out of here with some show of trying to arrange cargo. Best not to contact the black market here: they were likely to check him closer going out than coming in. But he could change Lucy’s name again, out at Tripoint—could risk a blown ship or a cut throat and do some nullpoint trading, sans customs, sans police, lying off at some place like Wesson’s and waiting for some ship that might be willing to trade with a freelancer, and better yet, some other marginer who might deal in forged paper. Risky business. Riskier still… with the military stirring about. An operation to tighten loopholes in which piracy was possible—also tightened loopholes in which marginers survived.

Union and Alliance in cooperation. He had never foreseen that. He swallowed the last of the dry sandwich, wadded the wrapper and thrust it back into his pocket, spacer’s reflex. The section seal was ahead, the office section, the military dock where militia were even more in evidence. He watched the overhead signs to find his way, finally located the customs office adjunct to the Dock Authority, halfway down the dock, and walked through the door. It was getting close to mainday. A line of applicants stood inside, spacers and ships’ officers with their own difficulties. A sign advised a separate window, a different procedure for ship clearance. He fished his papers out of his pocket and presented them at the appropriate window, and the young woman looked him in the eyes and glanced down again at the ID and Lucy’s faked papers. “Captain Stevens. There’s a call in for you.”

It started his heart to pounding; any anomaly would, in places such as this. “What ship?”

“Just a moment, sir.” She left the counter, took the papers with her. Terror verged on panic. He would have bolted, perhaps, with the papers-No. He would not. With the security seal on Lucy there was no way. A long counter, a bored clutch of clerks and business as usual, separated him from his title to Lucy, and making a row about it would draw attention. He leaned there, locked his hands on the counter to brace himself in his studied weariness and exasperation, hoping, still dimly hoping, that it was Allison Reilly with a parting message—(but she would not, never would, wanting no connection with him)—and they would give him his papers back and unlock his hatch for him. He cursed himself for ever agreeing to that seal; but he had been tired, his mind had been on Allison Reilly and his wits were not what they had been.

The official came back. His heart leapt up again. He leaned there trying to look put upon. “I’m really pretty tired,” he said. “I’d like to get that message later if I could.” That was what he should have said in the first place. That he finally thought of it encouraged him. But she looked beyond his shoulder at someone who had come up behind him, and that little shift of the eyes warned him. He turned about, facing station police.

It was not the scenario he had planned—his back to a customs counter, an office full of people who had no involvement in the situation; no gun in his pocket, Lucy’s papers in someone else’s possession, his ship locked against him. “Captain Stevens,” the policeman said. “Dockmaster wants to see you.”

Perhaps his face was white. He felt himself sweating. “It’s alterday.”

“Yes, sir. Will you come?”

“Is something out of order?”

“I don’t know, sir. I’m just asked to bring you to the offices.”

“Well, look, I’ll get up there in a minute. I need to settle something here with customs.”

“My orders are to bring you now. If you would, sir.”

“Look, they’ve got my papers tangled up here.—Ma’am, if I could have my papers back—” He turned belly to the counter again, expecting a heavy hand and cuffs on the instant. He tried, all the same, and the woman handed him the papers, which he started to put into his inside breast pocket. The officer stopped that reach with a grip on his wrist, patted his coat with a small deft movement even those standing closest might have missed, patted the other two pockets as well. “That’s all right, sir,” the officer said. “If you’ll come along now.”

He put the papers in his pocket, left the counter and went. The policeman laid no hand on him, simply walked beside him. But there was no escaping on Pell.

“This way.” The officer showed him not to the main elevators in the niner corridor, but to a service elevator on the dock. Other police waited there, holding the door open.

“I think I have a right to know what this is about,” Sandor protested, not sure that Union rights applied here at all, this side of the Line.

“We don’t know,” the officer in charge said, and put him into the lift with the other police, closed the door behind. “Sir.”

The lift whisked them up with a knee-buckling force, two, four, six, eight levels. Sandor put his hands toward his pockets, nervous habit, remembered and did it anyway, carefully. The door opened and let them out into a carpeted corridor, and one of the police took a scanner from his belt and took him by the arm, holding him still while he ran the detector over him. Another finished the job, waist to feet.

“That’s fine,” the officer said then, letting him go. “Pardon, sir.”

Maybe he had rights this violated. He was not sure. He let them take his arm and guide him down the corridor, a corporation kind of hall, carpeted in natural fiber, with bizarre carvings on the walls. The place daunted him, being full of wealth, and somewhere so far from Lucy he had no idea how to get back. Perhaps it was the shock of the strung-together jumps he had made getting here; maybe it was something else. His mind was not working as it ought; or it lacked possibilities to work on. His hands and feet chilled as if he were operating in a kind of shock. He was threadbare and shabby and as out of place here as he would be in Dublin’s fine corridors. Lost. There was money here that normally ignored nuisances his size, and somehow the thought of arguing a three thousand credit account in a place like this that dealt in millions-One of the police strode ahead and opened a door with a key card, let them into an office where a militia guard stood with a large, ugly gun at his side; and two more station security officers, and a man at a desk who might be a secretary or a clerk.

“Go on in,” that one said, and pushed a button at the desk con-sole. The militiaman opened the farther door and Sandor hesitated when the police did not bid to move. “Go on,” the officer said, and he went, far from confident, down an entry corridor into a large room with a U-shaped table.

All its places were filled, mostly by stationers silver-haired with rejuv; but there were exceptions. The woman centermost was one, a handsome woman in an expensive green suit; and next to her was another, a militia officer in blue, a pale blond man with bleak pale eyes.

“Papers,” the woman in the center said. He reached into his pocket and handed them to a security agent on duty in the room, who walked to the head of the U and handed them to her. She unfolded them in front of her and gave them a cursory scrutiny.

“Why am I here?” Sandor ventured, not loud, not aggressive. But it had never seemed good to back up much either. They just asked me to come up here. They didn’t say why.”

She passed the papers to the militia officer beside her. She looked up again, hands folded in front of her. “Elene Quen-Konstantin,” she identified herself, “dockmaster of Pell.” And he recalled then what was told about this woman, who had defied a Union fleet. He swallowed his bluffs unspoken, taking her measure. ‘There’s been some question about your operation, Captain Stevens. We’re understandably a little anxious here. We have statements by some merchanters that you’re under ban at Mariner, under a different name. On unspecified charges. This is hearsay. You don’t have to answer the questions. But we’re going to have to run a check. We’re quite careful here. We have to be, under circumstances I’m sure I don’t have to lay out for you. Your combine will be reimbursed for any unwarranted delays and likewise your housing and your dock charges will be at Pell’s expense during the inquiry. Unless, of course, something should turn up to substantiate the charges.”

It took a great deal to keep his knees steady. “There ought to be something a little more than hearsay for an impoundment. And the damage to my reputation—what repairs that?”

This is Alliance space, Captain. You’re not in Union territory any longer. Alliance sovereignty. You came here of your own decision, without a visa, which we allow. But you have to have one to operate here. I’m personally sorry for the inconvenience, and I assure you Pell’s inquiry will be brief, three days at maximum. There are several merchanters in from Mariner. We’ll be talking to them. You have a right to know that the investigation is proceeding and to confront complainants and witnesses whose testimony is filed to your detriment. You have a right to counsel; this will be billed to your combine, but should the charges prove false, as I said, Pell will stand good for the—”

“I don’t have that kind of operation.” Panic crept into his voice. It was in no wise acting. “I’m an independent under Wyatt’s umbrella. I pay all my own costs and I’m barely making it as it is. This is going to ruin me. I can’t afford the time, not even a few days. That comes out of the little profit I do make, and you’re going to push me right over into the loss column. They’ll attach my ship—”

“Captain Stevens, if you’d allow me to finish.”

‘This is something trumped up by some other marginer who doesn’t want my competition.”

“Captain, this is not the hearing. You have a right to counsel before making statements and countercharges and I would advise you to be careful. There are penalties for libel and malicious accusation, and the ship making charges against you will likewise be detained, likewise be liable for damages if the accusation is proved malicious.”

“And where do I get counsel? I haven’t got the funds. Just company funds. What am I supposed to do?”

Quen looked down the table to her left. Someone nodded. “Legal Affairs will help you select a lawyer.”

“And prosecute me too?”

“Captain, Pell is the only world in Alliance territory… unless you want a change of venue to Earth itself. Or extradition to Mariner. At your hearing you can make either request. But your appointed defender should make it only after you’ve had a chance to consider all the points of the matter. I repeat, this is not the hearing. This is only your formal advisement that allegations have been made, of general character and as yet undefined, but of sufficient concern to this station to warrant further investigation. Particularly since you are Union registry, since you’re not familiar with Alliance law, I do suggest you refrain from comment until you have a lawyer.”

“I’m not one of your citizens.”

“Presumably you’re seeking Alliance registry, which is the only way you can trade here. Now on the one hand, you’ll be seeking to prove the charges false; and on the other, if they are proved false, if your record is established, then your registry would be a matter of form. So if there’s really no problem, it should after all save you time you might spend waiting for forms and technicalities, and I might add, at station expense. If you hoped to clear all your papers and get cargo in a three-day stopover under normal circumstances, Captain, I’m afraid you were misled.”

“If it’s processed in that time and not after it—” He played for conciliation, took an easier stance, felt a line of sweat running down his face all the same.

“Quite so. I assure you it will be simultaneous.”

“I appreciate it” He folded his hands behind him and tried to look comforted. He felt sick. “Where am I supposed to stay, then? I’d like to have access to my ship.”

“Not yet”

“Accommodations dockside, then?”

“At any B class lodging.”

“Captain.” That from the militia officer. The voice drew his eyes in that direction. The blue uniform—was wrong somehow. Foreign. He was not used to foreignness. He had never imagined any current military force outside Union, which was all of civilization. The emblem was a sunburst on the sleeve, and several black bands about the cuff. “Commander Josh Talley, Alliance Forces. Officially—why are you here?”

“Trade.”

“For what?”

“Is that,” Sandor asked, looking back at Quen, “one of the things I should wait for a lawyer to answer? I don’t see I have to make my business public.”

“You’re not obliged to answer. Use your own discretion.”

He thought about it—looked back at Talley: a precise, military bearing, cold and clean, with a hardness unlike any merchanter he had ever seen. The eyes rested on him, unvarying, virtually unblinking, making him uneasy. “For the record,” he said, “I get some latitude from my combine. I was on the Viking-Fargone run. It never paid; and I thought maybe I could widen my operation a little, set up an account here and do better on a cross-Line run… my discretion. I have a margin to operate in. I moved it. Am moving it.”

“How much margin, Captain? Three thousand, as you claimed? And you look to compete with larger, faster ships? We’re interested in the economics of your operation. What do you haul, when you can get cargo? Small items—of high value and low mass?”

Suddenly the room was all too close and the air unbearably warm. “I couldn’t do much worse than where I was, that was all. Yes, I haul things like that. Station surplus. Package mail. Licensed Pharmaceuticals. All clean stuff. Dried foods. Sometimes I carry passengers who aren’t in a hurry and can’t afford better. I’m slow, yes.”

“And WSC has interest in a Pell base of operations?”

He weighed his answer, trying to remember what he might have said over the com when he was accounting for himself coming in. “Sir, I told you—my own risk. I figured I could get some station cargo. I heard it was good here.”

“Captain, I know something about Union law. The legal liabilities and the risks of your operation don’t leave much room for profit; and it seems to me very doubtful that your combine would leave a step like yours to an independent.”

“It’s not a company move. It’s a simple shift of a margin account.” He grew desperate, tried to make it sound like indignation. “I never violated the law and I came here in good faith. There’s no regulation against it on Unionside.”

“Financial arrangements on both sides of the Line have been– loose, true. And you fall into a peculiar category. I perceive you’re an excellent dockside lawyer. Most marginers are. And I’d reckon if your log and ledgers are put under subpoena… we’ll find they don’t exist, in spite of regulations to the contrary. In fact you’ll keep no more records than the Mazianni do. In fact it’s very difficult to tell a marginer from that category of ship—by the quality of the records they keep. What do you say, Captain? Could that account for your economics in a cross-Line run?”

If ever in his life he would have collapsed in fright it would have been then, under that quiet, precise voice, that very steady stare. His heart slammed against his ribs so hard it affected his breathing. “I’d say, sir, that I’m no pirate, and having lost my family to the Mazianni, I don’t take the comparison kindly.”

The eyes never flinched, never showed apology. “Still, there is no apparent difference.”

“Lucy doesn’t carry arms enough to defend herself.” His voice rose. He choked it down to a conversational tone as quickly, refusing to lose control. “You admit she can’t make speed. How is she supposed to be a pirate?”

“A Mazianni carrier could hardly pull up to a station for trade and conversation. But there is a means by which the Mazianni are trading with stations, in which they do scout out an area and the ships trading in it, mark the fat ones, and pick them off in the Between. Marginers undoubtedly figure in that picture, trading in the nullpoints, picking up cargo, faking customs stamps. Would you know any ships like that?”

“No, sir.”

“She moves fast when she’s empty, your Lucy”

“You can inspect her rig—”

“We have an unusual degree of concern here. The allegations made against you include a possible charge of piracy.”

“That’s not true.”

“We advise you that the Alliance Fleet is making its own investigation, apart from Pell Dock Authority. That investigation will take longer than three days. In fact, it will be ongoing, and it involves a general warrant, along with a profile of your ship and its internal identification numbers, a retinal print and voice print, which we’ll take before you return to dockside, and all this will be passed to Wyatt’s Star Combine and Mariner through diplomatic and military channels. Should it later prove necessary, that description will be passed to all ports, both Union and Alliance, present and future. But you won’t be detained on our account, once that printing has been done.”

“And what if I’m innocent? What kind of trouble am I left with? That kind of thing could get me killed somewhere, for nothing, some stupid clerk punching the wrong key and bringing that up, some ship meeting me at a nullpoint and pulling that out of library—you’re setting me up for a target.” He cast a desperate look at Quen. “Can I appeal it? Have I got a choice?”

“Military operations,” Talley said, “are not under civil court You can protest, through application to Alliance Council, or through a military court. Both are available here at Pell, although the Council has finished its quarterly business and it’s in the process of dispersing as ships leave. You’d have to appeal for a hearing at the next sitting, about three months from now. Military court could be available inside a month. You’d be detained pending either procedure, but counsel will be provided, along with lodging and dock charges, if you want to exercise that right. And you can apply for extensions of time if you need to call witnesses. Counsel would do that for you.”

“I’ll see what counsel says.”

“That would be wise,” Quen said. An aide had come in, padded round the outside of the U and slipped a paper under her hands. She read it and spoke quietly to the messenger, folded her hands over the paper on the table as the messenger slipped out again. “There is an intervenor in the case, Captain Stevens, if you’re willing to accept.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Reilly of Dublin Again has offered his onboard legal counsel. This would be acceptable to Pell.”

The blood drained toward his feet “Am I free to make up my own mind in the matter?”

“Absolutely.”

“I’d like to talk to them.”

“I think our business with you is done, pending your appointment with the military identification process.”

“But maybe I don’t want to go through that. Maybe—” He stared into a row of adamant faces. Stopped.

“Captain,” Talley said, “you have your rights to resist it. The military has its rights to detain you. Your counsel can interview you in detention and advise you. If you wish.”

He thought of jails, of a Dubliner arriving to fetch him out, one of Allison’s hard-eyed cousins. “No,” he said. ‘I’ll go along with the ID.”

That ought to do it, then,” Quen said, and looked aside at Talley. Talley nodded, once and economically. “Sufficient, then,” Quen said. “Our hopes, Captain Stevens, that there’s nothing but a mistake involved here. You’re free to address the board in general. We’ll listen. But I’d advise selecting your attorney before you do that. And prepare your statements with counsel’s advice.”

“I’ll reserve that, then.”

“Captain,” Talley said, “if you’d go with the officer.”

“Sir,” he said, quietly, precisely. “Ma’am.” He turned and walked out with the security officer, through the outer office and into the hall, trying in his confusion to remember where he was and which way the lift was and to reckon where he was being taken now. He was lost; he was panicked, inside corridors which were not Lucy’s, a geometry which was not the simple circle of dockside.

There was a small office down the corridor, two desks, a counter full of equipment. He stood, waited: a technician in militia blue showed up. “General ID,” the officer said, and the tech took him in charge, walked him through it, one procedure and the next, even to a cell sample.

It was done then, irrevocable. The information was launched, and they would send it on. The tech gave him a cup of cold water, urged him to sit down. “No,” he said. Maybe it was the look of him that won the sympathy. He failed at unconcern-looked back at the officer who had acquired a companion.

“Your party’s waiting for you,” the second officer said, “out by the lift.”

Allison, he thought, at a new ebb of his affairs. He should have accepted jail; should have refused the typing. He had fouled things up. But confinement—being shut up in a cell for Dubliners to stare at—being shut inside narrow station walls, in places he knew nothing about—

The officer indicated the door, opened it for him, pointed down the hall to the left “Around the corner and down.”

He went, turned the corner—stopped at the sight of the silver-coveralled figure standing by the lift, a man he had never met

But Dubliner. He walked on, and the dark-haired young man gave him no welcome but a cold stare, C. REILLY, the pocket said, on a broad and powerful chest. “Curran Reilly,” the Dubliner said.

“Where’s Allison?”

“None of your business. You’re through getting into trouble, man. Hear me?”

“I’m headed down to the exchange. I’m not looking for any.”

“You hold it.” An arm shot out, blocking his arm from the lift call button. “You got any enemies in port, Stevens?”

“No,” he said, resisting the impulse to swing. “None that I know about. What’s your percentage in it?”

Curran Reilly reached in his coveralls pocket and pulled out several credit chits, thrust them on him and he took them on reflex. “You take this, go get breakfast, book into the same sleep-over as last night. You don’t go to the exchange. You don’t go near station offices. You don’t sign anything you haven’t signed already.”

“I’ve been printed.”

“A great help. Really great.”

He thrust the credits back. “Keep your handout I’ve got my own funds.”

“The blazes you have. Shut your mouth. You go to that sleep-over and stay there and that bar next door. We want to know right where to find you. We don’t want any complications and we don’t want anything else stupid on your part. Keep that money and don’t try to touch what you arrived with. You’ve got enough troubles.”

He stared into black and angry eyes, smothered his own temper, afraid to walk away. “So how do I find the place? I’m lost.”

The Dubliner reached and pushed buttons on the lift call. “I’ll get you there.”

“Where’s Allison?”

“Don’t press your luck, mister.”

“That’s Captain, and I’m asking where Allison is. Is she in trouble?”

“Captain.” The Dubliner hissed, half a laugh, and the scowl darkened. “Her business is her business and none of yours, I’m telling you. She’s working to save your hide, and I’m not here because I like the company.”

“She’s not spending any money—”

“You’ve got one track in your mind, haven’t you, man? Money. You’re a precious dockside whore.”

“Go-”

“Shut your mouth. You take our charity and you’ll do as you’re told.” The car arrived and the door whipped open. The Dubliner held it for him and he got in, with rage half blinding him to anything but the glare of lights and the realization that they were not alone in the car. Curran Reilly stepped in: the door shut and the car shot away with them. A pair of young girls stood against the rail on the far side of the car; an old man in the front corner. Sandor put his hands in his pockets and felt the Reilly money in his left with the sandwich wrapper, with the adrenalin pulsing in him and Curran Reilly standing there like a statue at his right. The girls whispered behind their hands. Laughed in adolescent insecurity. “It’s him” he heard, and he kept staring straight ahead, an edge of raw terror getting through the anger, because his face was known—everywhere. And he had to swallow whatever the Dubliner said and did because there was no other hope but that.

If the Reillys were not themselves plotting revenge, for the stain on their Name.

A long, slow trip on Dublin, Allison had warned him, if he crossed her cousins. Revenge might recover Dublin’s sullied Name, when the word passed on docksides after that.

But he went where he was told. He knew well enough what station justice offered.