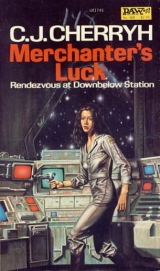

Текст книги "Merchanter's Luck "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

“I don’t need your help.” She snatched at the straps he held and failed to get them back. “Just drop them in the corridor. I’ll come back and get them.”

“You can’t take any help, can you?”

She walked off. “From the man who took a half million credits with never a thanks—” She stopped and looked back when he started after her with the bag, almost collided. “You choke on the words, do you, Stevens?”

“Thanks,” he said. “That do it?”

“Just bring the bags.” She turned about again, stalked one door farther and opened the compartment, tossed her belongings through the door and stood aside outside it, a wave of her hand indicating the way inside.

He tossed them after the first. “What about thanks?” he said.

“Thanks.” She shut the door, still outside it.

“Look, you think you have to go through this to tell me no? I can take no. I understand you.”

“What’s the real name?” Quietly asked. Decently asked.

“Think it’d change your mind?”

“No. Not necessarily. But I think it says something about no trust.”

“First name’s Sandor.”

A lift of both dark brows. “Not Ed, then.”

“No.”

“Just—no. Nothing further, eh?”

He shrugged. “You’re right. It’s not dockside, is it?” He looked into dark eyes the same that he had seen one night in a Viking bar, and he was as lost, as dammed up inside. “Can’t break things up when they get tangled.”

“Can’t,” she said. “So you understand it: I might sleepover with you when we get to Venture. I might sleepover with someone else instead. You follow that? I came. But if you reckon I came with the loan, figure again.”

“I never,” he said, “never figured that.”

She nodded. “So we take this a little slower, a lot slower.”

“So suppose I say I’d like to take it up again at Venture.”

She stared at him a moment, and some of the tenseness went out of her shoulders. “All right,” she said. “All right. I like that idea.”

“Like?”

“I’m just not comfortable with it the other way.”

“Might change your mind someday?”

“Ah. Don’t push.”

“I’m not pushing. I’m asking whether you might see it differently.”

“The way you look at me, Stevens—”

“Sandor.”

“—makes me wonder.”

“I understand how you feel. About being on the ship. Maybe my talking like that, in front of the others back there—is a good example of what you’re worried about. I didn’t think how it went out. I know you know what you’re doing. I just had my mind full… I’ve just got some things with the ship I haven’t got straight yet. Things—never mind. I just have to get over the way I’m used to doing things. And dealing with the kind of crew I’m used to getting.”

She tightened her mouth in a grimace that looked preparatory to saying something, exhaled then. It seemed to have slipped her. “All right. I understand that too. You mind fixing comp in my quarters while we’re at it?”

His heart did a thump, attack from an unexpected direction. “I’ll get it straightened out. Promise you. After jump.”

“Security locks?”

They seemed like a good thing when I had unlicensed crew aboard.”

“Well, it’s a matter of the comp keys, isn’t it?”

It was not a conversation he wanted. Not at all. “Look, we haven’t got time for me to get them all down or for you to memorize them. We’re heading up on our exit.”

“Is there something I ought to know?”

“Maybe I worry a bit when I’ve got strangers aboard. Maybe that’s a thing I’ve got like you’ve got attitudes—”

Her back went stiff. “Maybe you’d better make that clear.”

“I don’t mean like that. I’m dead serious. That’s all I’ve got, those keys, between me and people I really don’t know that well. And maybe that makes me nervous.”

The offense at least faded. The wariness stayed. “Meaning you think we’d cut your throat.”

“Meaning maybe I want to think about it.”

“Oh, that’s a little late. A little late. We’re on this ship. And we’re talking about safety. Our safety. If something goes wrong on my watch, I want those keys. None of this nonsense.”

“Look, let’s get through jump first. I’ll get you a list then.”

“Through jump, where we’re committed. I don’t consider the comp a negotiable item.” She jabbed a thumb toward her cabin door. “I want my comp in there operative. I want any safety locks in this ship off. I want the whole system written down for all of us to memorize.”

“We haven’t got time for that. Listen to me. I’m taking Lucy through this jump; I don’t want any question about that. I’ll see how you handle her; and then maybe I’ll feel safe about it. You look good. But I’m reckoning you never handled anything but sims in your life. And I’m sleeping on the bridge if I have to, to see no one makes a mistake. I’m sorry if that ruffles your pride. But even I haven’t a good notion of what Lucy feels like loaded.”

“Don’t you?” Suspicion. A sudden, flat seizure of attention.

“I’ll take the locks off when I know who I’m working with.” He thrust his hands into his pockets, started away, to break it off. Instinct turned him about again, a peace offering. “So I’m a bastard. But Lucy’s not what you’re used to, in a lot of senses. I haven’t nursed her this far or got you out here to die with, no thanks. I’m asking you—I want you all on the bridge when we go into jump.”

“All right,” she said. A quiet all right. But there was still that reserve in her eyes. “You watch us. You see how it is. Sims, yes.”

“And backup bridge. But you catch me in a mistake, you do that.”

“I don’t think I will,” he said softly. “I don’t expect it.”

“Only you’re careful, are you?”

“I’m careful.”

They approached jump, a sleep later, a slow ticking of figures on the screen—a calm approach, an easy approach. Sandor checked everything twice, asked for data from supporting stations, because jumping loaded was a different kind of proposition. Full holds, an unfamiliar jump point—there were abundant reasons to be glad of additional hands on this one, “Got it set,” he said to Allison, who sat number two. “Check those figures, will you?”

“Already doing that,” Allison said. “Just a minute.”

The figures flashed back to him.

“You’re good,” he said.

“Of course.” That was the Dubliner. No sense of humility. “We all are. We going for it?”

“Going for it.—Count coming up. Any problems?—Five minutes, mark. Got our referent.” He reached for the trank and inserted the needle. There was no provision on this one but a water bottle in the brace, for comfort’s sake. No need. They would exit at a point named James’s, and laze across it in honest merchanter fashion; and then on to Simon’s Point, and to Venture.

The numbers ticked on.

“Message from Pell buoy,” Neill said, “acknowledging our departure.”

No reply necessary. It was automated. Lucy went on singing her unceasing identification, communicating with Pell’s machinery.

“Mark,” Sandor said, and hit the button…

Chapter XII

… Down again, into a welter of input from the screens, trank-blurred. Sandor reached in slow motion and started to deal with it. Beside him, the others—and for a moment his mind refused to sort that fact in. There was the mass which had dragged Lucy in out of the Dark… they were at James’s Point, Voyager-bound; and Ross’s voice was silent.

“Got it,” Allison was saying beside him, icy-cold and competent. “Just the way the charts gave it…”

He was still not used to that, a stranger-voice that for a moment was desolation… but it was her voice, and there was backup on his right, all about him. “Going for dump,” he said.

And then Curran’s voice: “We’re not alone here.”

It threw him, set his heart pounding: his hand faltered on the way to vital controls. Velocity needed shedding, loaded as they were, tracking toward the mass that had snatched them. Things happened fast in pre-dump, too fast—

“Standing by dump,” Allison said.

“That’s Norway,” Neill said then.

He hit the dump, kicked in the vanes, shedding what they carried in a flutter of sickening pulses. “She still with us?” he asked, meaning Norway. Sensor ghosts could linger, light-bound information on a ship which had left hours ago. No way to discern, maybe—but he wanted his crew’s minds on it Wanted them searching. Hard.

“Better set up the next jump in case,” Allison said. “I don’t trust this.”

“Outrun that?” Sandor focused on the question through the trank haze. “You’re dreaming, Reilly.” They kicked off velocity again, a numbing pulse that scrambled wits a moment He blinked and reached an unsteady hand toward comp, started lining the tracking up again.

“We’re in,” Allison said. “That’s got us on velocity.”

“Getting nothing more than ID transmission,” Neill said.

“Got a solid image,” Curran said. “They’re close. That’s confirmed, out there, range two minutes.”

The image hit his screen, transferred unasked. “Should I contact them?” Neill asked. “I’m getting no com output”

“No.” He blinked, the sweat running on his face, concentrated on the business in front of him—and that ship out there, right on them as a warship reckoned speed, silent, sullen—was Mazianni in all but name. He got a lock on the reference star, saw the figures come up congruent, fed them in and sent the information over to Allison’s console.

“Got it clear,” Allison said. “Still want me to take it, or do you want to hold it?”

He caught his breath, sent a desperate look over all the board in front of him. Vid showed them nothing but stars; other sensors showed the G well itself, the mass, the heat of an almost-star that was the nullpoint. And the pockmark that was Norway. A situation. A raw Dubliner recruit asking for the board, maybe not particularly anxious to have control at the moment. He shunted things over to the number two board. “She’s yours.” His voice was hoarse. He pretended nonchalance, let go the restraints, reached for the water bottle and drank. “Here.”

Allison looked aside, a distracted flick of her eyes, took the bottle and drank a gulp, passed it back. He slipped it back into the brace and hauled his way out of the cushion.

Looked back again, toward the screens, with a tightness about his throat.

Norway. And Mallory was saying nothing. The presence did not surprise him. Somehow the foreboding silence did not either.

“Mainday shift,” he said, “let alterday have it.”

“Sir,” Neill muttered, the first courtesy of that kind he had gotten out of them. Natural as breathing from a Dubliner on a bridge. Spit and polish, and he finally got it out of them. Neill stirred out of his place.

“Got another one,” Deirdre said suddenly. “Got another ship out there.”

Sandor crossed the deck to his chair in a stride and a half, flung himself into it.

“ID as Alliance ridership Thor” Deirdre said. “Coming out of occultation with the mass.”

“One of Mallory’s riders,” Allison muttered.

“If they’ve got the riders deployed—” Neill said, back at his own post.

No one made any further surmises.

“Second signal,” Deirdre said. ‘The ID is ridership Odin.”

“Deployed before we dropped in here,” Sandor said.

“What do you know about it?” Curran asked.

“Sir,” Sandor said.

Curran turned his head. “From back at Pell, sir—did you expect this? What was it Mallory said?”

“That she’s watching the nullpoint. I’m not at all surprised she’s here. Or that she’s not talking. What would you expect? A good morning?”

“Lord help us,” Allison muttered. “And what kind of cargo have they handed us, that we get Mallory for a nursemaid?”

“I don’t ask questions.”

“Maybe we should have,” Curran said. “Maybe we should get ourselves a couple of those canisters open.”

“I’m reckoning you’d find chemicals and station goods,” Sandor said. “I’d even bet it’s Konstantin Company cargo, the same as we would have gotten. I don’t think that’s what Mallory’s interested in at all. I think we’re being prodded at.”

“Because they’re still breathing down your neck: that’s what we’ve inherited—your own record with them. It’s some kind of trap, something we’ve walked into—”

“You applied for Venture routing, Mr. Reilly. Dublin handed a marginer a half a million, stifled an inquiry, and headed us for Pell’s most sensitive underside. A Unionsider. Put it together. Union and Alliance may be at peace, but Mallory’s got old habits. Maybe you’d better think like a marginer, after all. Maybe you’d better start figuring angles, because they have them in offices, the same as dockside. And the powers that be on Unionside had them, when they got cooperative and wanted Dublin this side of the Line. But maybe you’d know that. Or maybe you should have sat down and figured it”

“If you’ve got it figured, then say it. Let the rest of us in on it”

“Not me. I don’t know. But we’re not making any noise we don’t have to. We tiptoe through this point and get that cargo to-”

“Moving,” Deirdre said. “Thor’s moving on intercept”

Sandor dived for the board, a sweat broken out on his sides, sickly cold on his face. He stopped his hand short of the controls, clenched it there in the reckoning that there was nothing they could do… No arms the equal of that; no ability to run, loaded as they were.

(Ross?… Ross… What’s to do?)

“Contact them?” Allison asked.

“No.”

“Stevens… Sandor… what precious else can we do?”

“We keep going on our own business. We let them escort us through the point if that’s what they have in mind. But we don’t open up to them. Let the contact be theirs.”

She said nothing. Helm was still under her control. The ship kept her course as she was, no variances.

“Message incoming,” Neill said: “They say: Escort to outgoing range. They say: request exact time and range our departure from Pell.”

“They’re tracking us,” Curran muttered.

“They repeat. They want acknowledgment.”

“Acknowledge it,” Sandor said. “Tell them we’re figuring.” He sat down at comp, keyed through and downed the sound, started calling up the information.

“Sir,” Neill said. “Sir, I think you’d better talk to them. They’re insisting.”

He snatched up the audio plug and thrust that into his ear, adjusted the mike wand from the plug one-handed. “Feed it through.”

“… accurate,” he caught. “Lives ride… on absolute accuracy, Lucy. Do you copy that?”

“Say again.—Neill, what’s he talking about, lives?”

“To whom am I speaking?” the voice from the ridership asked. “To Stevens?”

“This is Stevens, trying to do your calculations if you’ll blasted well give me time.”

“Your ship will proceed to Voyager as scheduled. You’ll dock and discharge Voyager cargo. You have three days for station call, to the hour. And you’ll return to this jump point on that precise schedule.”

“Request information.”

“No information. We’re waiting for that departure data.”

“Precise time local: 2/02:0600 mainday; locator 8868:0057: 0076.35, tracking on recommended referents, Pell chart 05700.”

“2/02:0600 precise?”

“You want our mass reckoning?” He was scared. It was a track they were running, no question about it He flung out the question to let them know he knew.

“You carrying anything except our cargo, Lucy?”

“Nothing.” The air from the vent touched sweat on his face. “Look, I’ll run that reckoning on my own comp and give you our RET.”

“Is 0600 accurate?”

“0600:34.”

“We copy 0600:34. Your reckoning is not needed, Lucy.”

“Look, if you want data—”

“No further questions, Lucy. We find that agreeing with our estimate. Congratulations. Endit.”

“We’re in trouble,” Allison said.

“They’re accounting for our moves,” he said. “Just figuring. I’d reckon Pell buoy scheduled us pretty well the way they set it up.” He shut down comp, back under lock. “So they know now what our ETA is with the mass we’re hauling: every move we make from now on—”

“I don’t like this.”

“Every point shut down. Everything monitored. We make a false move—and we’re in trouble, all right” He thrust back from controls. “Nothing’s going to move on us here while that’s out there. Shut down to alterday. Mainday, go on rest.”

“Look,” Curran said, twisting in his cushion. “We’re not going through Pell System lanes anymore. We’re not sitting here to do autopilot, not with them breathing down our necks and wanting answers.”

“I’m here,” he said, looking back. “I’m not leaving the bridge: going to wash, that’s all; and eat and get some sleep right back there in the downside lounge. You call me if you need anything.”

“Instructions,” Allison said sharply, stopping him a second time. “Contingencies.”

“There isn’t any contingency. There isn’t any blasted thing to do, hear me? We’ve got three days minimum crossing this point, and you let– He saw her face, which had gone from appeal to opaque, unclenched a sweating hand and made a cancelling gesture. They’re one jump from Mazianni themselves, you know that? Let’s just don’t give them excuses. We’re a little ship, Reilly, and we don’t mass much in any sense. Accidents happen in the nullpoints. Now true a line crosspoint and don’t get fancy with it.”

She gave him a long, thinking stare. “Right,” she said, and turned back to business.

He walked, light-headed, back to the maintenance area shower, not to the cabins; had no cabin. The others had. He was conscious of that. And he had to sleep, and they chafed at the situation. He stripped, showered, alone there with the hiss of the water and the warmth and a cold knot in his gut that did not go away. Mazianni ships out there… and they had died out there, in the corridor, on the bridge, bodies fallen everywhere. Reillys sat and joked and moved about, but the silence was worse than before, deep as that in which Lucy moved now, with Mallory.

(Armored intruders, a Name—a Name on them, on the armor; but he could never focus on it, never get it clear in his mind; he had never talked about that with Ross; never wanted to know– until it was too late, and Ross never came back to the ship…)

He had thought for a day on Pell that he was free, clear. But it was with them. It ran beside them, the nightmare that had been following Lucy for seventeen years.

They took it three and three, she and Curran, on a twelve-hour watch: three hours on and three off by turns, their own choice, Allison sat the number two chair on her offtime or padded quietly about the bridge examining this and that, while their military escort kept its position and maintained its silence.

From Sandor/Stevens, who had made his bed aft of the bridge in the indock lounge—not a sound, although she suspected that he wakened from time to time, a silent, furtive waking, as if he only grazed sleep and came out of it again. And from Neill and Deirdre, asleep in cabins four and five respectively, no stirring forth. Exhausted: none of them was used to this, and what kept Stevens going—

What kept Stevens going bothered her, at depth and at every glance back in his direction. Something wrenched at her gut—the memory of an attraction; the indefinable something that had made her crazy on Viking, that had gotten her linked with a no-Name nothing in the first place. Owner of his ship, he had said, in that bar; and maybe that had been enough, with enough to drink and a mood to take chances.

Not quite dead, that gut-feeling. And she had watched the man drawn thinner and thinner, from haggard to haunted—not sleeping now, she was sure of it. Not able to sleep. That ship out there, that was one good cause. Or the cumulative effect of things.

And he was not about to trank out, no, not with the comp locked up and a warship on their necks; with two Reillys at the controls.

She and Curran talked, when they sat side by side at the main board, spoke in low tones the fans and the rotation could bury. They talked operations and equipment and how a man could have run a ship solo, what failsafes would have to be bypassed and how a man could talk his way past station law.

She reckoned all the while that they might be overheard. Quiet, she signed when Curran got too easy with the remarks. Curran rolled his eyes to the reflective screens and back again, reckoning what she reckoned. *No sleep, he signed back, the kind of language that had grown up over the years on Dublin, practiced by crew at work in noise, embellished by the inventive young and only half readable by outsiders. *Watching us.

*Yes.

*Crazy.

She shrugged. That was a maybe.

*Care? A touch at the heart, a swift touch at the head, sarcastically.

She made a tightening of her jaw, an implied gesture of her chin to the ship that paced them. *That. That concerns me.

*He keeps the comp keys.

*He’s afraid.

*He’s crazy.

She frowned. *Probable, she agreed.

*Do something.

There was no silence in sign. It translated as I won’t. She turned a degree and looked Curran in the eyes.

This was her rival, this cousin of hers, the one that pushed, all the way, all the years. It was yang and yin, the both of them, that made alterday Third what it was, and carried Deirdre and Neill.

Curran never stopped, never let up. She valued him for that, knew how to reckon him, how he wanted the number one seat, forever wanted it. It was one thing when there were twenty ahead of them—and another when they sat sharing a command. Watch it, she made her look say; and he understood. She read it in his eyes as easy as from a page.

Number two, she thought of him. And she caught herself thinking it with a stab of cold, that that was how it was. There was a man who had this ship, and there was a working unit of Reillys who knew each other’s signals and had no need of explaining how it worked, who looked down familiar perspectives and knew what they were to each other and where all the lines were. Number two to her: it fell that way in seniority by two days, two days between her and Curran, between her and a man who would have been as good, at least in his own reckoning. Who could not have gotten them what she had gotten—

–not the same way, she could reckon him saying, raw with sarcasm.

But Curran never saw any way but straight ahead. Would never have blasted them out of their inertia. Would never have taken any chance but the one he was born with: dead stubborn, that was Curran. And it was his flaw. Possibly he knew it. It was why he was loyal: the same inability to swerve. It was a different loyalty from Deirdre’s, which was a deep-seated dislike of a number one’s kind of decisions; or than Neill’s, which was a tongue-tied silence: Neill’s mind went wider than some, so it took him longer to put his ideas together—a good bridge officer, Neill, but nothing higher. She knew them. Knew what they were good for and how the whole worked, stronger than its parts. She looked down from where she sat and their reflexes all went toward each other and toward her in a sequencing so smooth no one thought about it.

She was number one to them. To Curran she had to be. To justify his taking orders and not giving them, she had to be. And the others—it all broke apart without herself and Curran at their perpetual one-two give and take. Curran was jealous of Stevens, she realized that all in a stroke, a jealousy that had nothing to do with sex; with a pairing, yes; with a function like right hand and left. For her to form another kind of linkup, taking another man in a different way, in which an almost-brother could not intervene, in which he had no place—What was Curran then? she thought—too proud to settle to Deirdre and Neill’s partnership, and cast out of hers in favor of a stranger met in a sleepover. He had to go on respecting her judgment: that was part of his rationale. But that left him. That flatly left him.

She cast a second and sidelong look at her cousin, settling deeper into the cushion, folding her arms. “I’ll think of something,” she said.

“Going to eat?” he asked after a moment.

She looked at the elapsed time. 1101. She nodded, got out of the seat and walked off toward the galley.

A cold sandwich, a cold drink from storage… mealtime, as they reckoned time aboard, from the time of their arrival at the nullpoint. There was no need to force a realtime schedule on tired bodies, no need to reckon realtime at all except in communications, and they were getting no more of that. They had become introverted in their passage, disconnected from other time-scales. And there was, when all the movement and human noise was absent—a silence that made her eat her sandwich pacing the small floor space of the galley; that sent her eye to the vacant white plastic tables and benches of the galley mess, and her mind to spacing out the number that could have sat at the tables-Thirty. About thirty. Double that for mainday and alterday shifts, a ship’s crew of about sixty above infancy. And the vacant cabins and the silences…

She had expected a lot of 1 G storage on the ship, a lot of the ring given over to cargo. Customs would expect that. It was a question how far customs would break with courtesies and search the cabins: more likely, they contented themselves with the holds and did a tight check of the flow of goods on and off. A perfect setup for a smuggler, nested in a ship like this, with a good story about pirates and lost family.

But a woman had lived in her cabin before her. Another of Stevens’ women, might be… but there were the other cabins, all lived in like the first several—they assumed. She had clambered in and out of the barren, dark-metal core storage, entered all the holds they used in dock… but the ring beyond the downside area and the cabins and the galley she had not seen. None of them had. They were still visitors on the ship they crewed.

She finished the sandwich, tossed the drink container into the waste storage, and the sound of the chute closing was loud.

1136. There was time enough, in her free hour, to walk round the rim. To come up on Outran from the other corridor that let out onto the bridge.

She left the galley area, rejoined the central corridor that passed through that, walked past other doors, all cabins, by the numbers of them. She tried a door, found it unlocked. The interior was dark and bitter cold. Power-save. A cabin, with the corner of an unmade bed showing in the light from the door. Rumpled sheets. She logged that oddity in her mind, closed the door and walked on, to an intersecting corridor. She entered it, found another bank of cabins behind the first, a dark corridor of doors and intervals. The desolation afflicted her nerves. She walked back to the main corridor, kept going, the deck ahead of her horizoning down as she traveled.

A section seal was in function: she came on it as a blank wall coming down off the ceiling and finally making an obstacle of itself. Maybe four seals—around the ring. Four places at which the remaining sections could be kept pressurized, if something went wrong. It sealed off the docking-topside zone, the loft.

She stopped, facing that barrier, her heart beating faster and faster—looked at the pressure gauge beside the seal manual control, and it was up.

The loft… was the safety-hole of the young on every ship she knew of. Farthest from the airlock lifts; farthest from the bridge, farthest from accesses and exits. And sealed off. It might open. It might; but a section seal was for respecting: gauges could be fatally wrong, for everyone on the ship.

And no one was ass enough to keep hard vacuum in the ring, behind a closed door.

She hesitated one way and the other. Caution won. She reckoned the time must be getting toward 1200—no time and no place to be late. She turned about again—faced Stevens.

“Hang you, coming up on a body—”

“It’s cold in there,” he said. He was barefoot, in his robe, his hair in disarray.

“What’s there?” she asked. Her heart had sped, refused to settle. “Cargo space?”

“Used to be the loft. Sealed now. I’ll turn the heating on in my watch. I didn’t think of it. Never needed to go there.”

“You give me the comp and I’ll fix it.”

He blinked. She wished suddenly she had not said that, here, her back to the section seal, halfway round the ring from Curran. “I’ll fix it,” he said. “I’ll do it now if you like.”

“You’re supposed to be off. You have to follow me around?”

Another slow blink. “Got up to get a snack. Thought you were in the galley.”

“I’m supposed to be on watch.” She walked toward him, past him, and he fell in with her, walked beside her down the corridor into the galley. She stopped there and he stopped and stood. “Thought you were going to get something.”

He nodded, went over to dry storage and rummaged out a packet, tore it with his teeth and got a glass. His hands shook in pouring it in, in filling it from the instant heat tap.

“Lord,” Allison muttered, “your stomach. You shouldn’t drink that stuff when you’ve got a choice.”

“I like it.” He grimaced and drank at it, swallowed as if he were fighting nausea.

“You’re wiped out, Stevens.”

“I’m all right.” His eyes had a bruised look, his color sallow. He took another drink and forced that down. “Just need to get something on my stomach.”

“You watching us, Stevens? You don’t want us loose unwatched? I don’t think you’ve been sleeping at all. How long are you going to keep that up?”

He drank another swallow. “I told you how it’s going to be.” He turned, threw the rest of the brown stuff in the glass into the disposal and put the glass in the washer. “ ‘Night, Reilly. Your noon, my midnight.”

“Why don’t you go get in a real bed, Stevens, a nice cabin, turn out the lights, settle down and get some sleep?”

He shrugged. Walked off.

1158, She was due. She walked behind him, watched his barefoot, unsteady progress down the corridor, walked into the bridge behind him and stood there watching him find his couch in the lounge again. He lay down there on his side, pulled the blankets about him, up to his chin, stiff and miserable looking.

The gut-feeling was back, seeing the disintegration, a man coming apart, biological months compressed into days—hell on a solo voyage while Reillys sipped Cyteen brandy.

She looked at Curran, whose eyes sent something across the bridge—impatience, she thought. She was late. Curran would have seen Stevens leave; she imagined his fretting.

“Your turn,” she said, coming to dislodge him from the number one seat “Any action?”

“Nothing. Everything as was.”

She settled into the cushion. Curran lingered, tapped her arm and, shielded by the cushion back, made the handsign for question.

* Negative problem, she signed back. And then a quick touch at Curran’s hand before he could draw away. *We two talk, she signed further. *Our night.