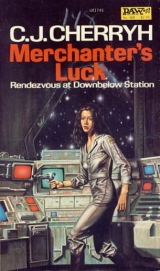

Текст книги "Merchanter's Luck "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

They gained no numbers in a generation: the matrilineal descent of merchanters generated new Dubliners of sleepover encounters with more concern for too few children than too many: another was always welcome, and if one wanted half a dozen, and another wanted none, that was well enough: it all balanced out from one generation to the next: Ma’am and Mina and Allison Senior came down, among others, to Megan and Geoff. Geoff had no line on Dublin, being male; but Megan had her and Connie, which balanced out; and Connie was already taking the line down another generation. Only rejuv kept five and sometimes six generations living at once: like Ma’am, who was pushing a hundred fifty and had faded only in the last decade, Ma’am, who had been Com 1 so long her voice was Dublin’s in the minds of everyone. It still made Shockwaves, thin as it had gotten, when Ma’am made it snap and handed out an order; and there was still the retired Old Man, who had been the Old Man for most of Allison’s life, and seldom got about now, snugged in his cabin that was downmost during dock, attended by someone always during jump, listening to tapes for his entertainment and sleeping more and more.

Allison herself… was Helm 21, which was status among the unposteds, Third Helm’s number one of the alterday shift. What do you want to be? Megan had asked her as early as she could remember the question. When a Dubliner was taking his first study tapes he got the Question, and started learning principles before awkward fingers could hold a pen or scrawl his letters, tapestudy from Dublin’s ample library. So what do you want to be? Megan had asked, and she had wanted to be bridge crew, where lights flashed and people sat in chairs and did important things, and where the screens showed the stars and the stations. What do you want to be? The question came quarterly after that, and it went through a range of choices, until at ten: I want to be the Old Man, she had said, before she had hardly gone out on a station dock or seen anything in the universe but the inside of Dublin’s compartments and corridors. The king of the universe was the Old Man who sat in the chair and captained Dublin, the Number One mainday captain, who ruled it all.

Be reasonable, Megan had told her then, taking her in the circle of her arm, setting her on the edge of the bed in her quarters and trying to talk sense into her. Only one gets to be the Old Man; and you know how many try the course and fail? Maybe one in four survives the grade to get into the line; and one in fifty gets to Helm 24, up where you’re even going to sit a chair on watch; and after that, age is against you, because the sitting captains are too young. You go ask in library, Allie, how long the sitting captains are going to live, and then you do the math and figure out how long the number two chairs are going to live after taking their posts behind them, and how long it takes for Helm 24 to work up to posted crew.

Can’t I try? she had asked. And: yes, you can try, Megan had said. I’m only telling you how it is.

Maybe there’ll be an accident, she had thought to herself, with a ten-year-old’s ruthless ambition: an accident to wipe out everyone in Second Helm.

You study everything, Megan had said, when she had complained about learning galley maintenance; the Helm course fits you for everything. So if you fail, you drop into whatever other track you’re passing. You think Helm’s just sitting in that chair: it’s trade and routings; law; navigation and scan and com and armaments; it’s jack and jill of all trades, Allie, ma’am, and doing all the scut before you hand it out, and you can always quit, Allie, ma’am.

No, ma’am, she had said, and swallowed all they gave her, reckoning to be stubbornest the longest, and to make it all the way, because there was a craziness in her, that once launched, she had a kind of inertia that refused to be hauled down. She was Helm 21, and when Val retired as she was likely to, Helm 6 and on the fading edge of rejuv, she would be Helm 20, and one more Dubliner got a post as Helm 24. She walked wide among the unposteds, being Helm. It had its perks. But Lallie, over there, Maintenance 196, was Second Maintenance second shift alterday at barely twenty-one, posted main crew before her hair grayed, while Helm 21 had little chance indeed, with a possible forty years until another seated Helm decided to give it up and retire. She would be on rejuv before the list got her past Helm 20, would still be lording it over the unposteds, silver-haired and still not able to cross the line into the posteds lounge, still waiting, still working the number two bridge to stay current.

She shut her eyes, leaned back, seeing blue dock again, and soldiers in their black uniforms. They talked about opening up Sol trade, shut down since the war; about opening the mothballed stations of the Hinder Stars. They talked new routes and profits to be made—putting their hand into Alliance territory, creating a loop that would link the Union stars to the Pell-based Alliance. Trade and politics.

So much she knew, sitting in on Dublin executive councils, which was all of Helm and only sitting crew of other tracks. She knew all the debate, whether Dublin should take the chance, whether they should just sit out the building and wait for the accomplished fact; but Dublin had always stood with one foot on either side of a crisis, always poised herself ready to move to best advantage, and the Merchanter’s Alliance, once an association of merchanter captains who disputed Union, now held the station at Pell’s Star for a capital, declared itself a sovereign government, passed laws, in short… looked like a power worth having a foot inside. A clean record with Union; a clean record with the Alliance thus far, since Dublin had operated far out of the troubled zones during the war—she could get herself a Pell account opened and if that new trade really was opening up there, then Dublin could get herself dual papers. Union Council was in favor of it, wanted moderates like themselves in the Alliance, good safe Unionside haulers who would vote against Pell-side interests as the thing got bigger. Union talked about building merchant ships and turning them over to good safe Unionsiders like Dublin to increase their numbers—which talk quickened Allison’s pulse. A new ship to outfit would strip away all the Second Helm of Dublin, and get her posted on the spot. She had lived that thought for a year.

But more and more it looked like a lot of talk and a maintenance of the status quo. Rapprochement was still the operative word in Union: Alliance and Union snuggling closer together after their past differences. Recontacting Sol, after the long silence, in an organized way. Clearing the pirates out. All merchanters having equal chance at the new ships that might be built

Hopes rose and fell. At the moment they were fallen, and she took wild chances on dockside. Geoff was right. Stupidity. But it had helped, with the soldiers crawling all over station that close to crossing the Line into foreign space. So she scattered a bit of her saved credit on a fellow who could use a good drink and a good sleepover. In a wild impulse of charity it might have been good to have scattered a bit more on him: he looked as if he could have used it… but touchy-proud. He would not have taken it. Or would have, being hungry, and hated her for it. There had been no delicate way. He fell behind her in her mind, as Viking did, as all stations did after they sealed the hatch. If she thought persistently of anyone, it was Charlie Bodart of Silverbell, green-eyed, easygoing Charlie, Com 12 of his ship, who crossed her path maybe several times a loop, Silverbell and Dublin running one behind the other.

But not now. Not to Pell, across the Line. Good-bye to Silver-bell and all that was familiar—at least for the subjective year. And it might be a long time before they got back on Charlie’s schedule —if ever.

A body hit the cushion beside her, heavy and male. She opened her eyes and turned her head in the din of voices. Curran.

“What,” Curran said, “hung over? You’ve got a face on you.”

“Not much sleep.”

“I’ll tell you about not much sleep.”

“I’ll bet you will.” She looked from him to the clock, and the bell was late. “I got along. I got those fiches too. And a couple of bottles.”

“Well have those killed before we get to Pell.”

“We’ll have to kill them at dock if they don’t get the soldierlads organized and get us out of here.”

“I think they’ve got it straightened away,” Curran said. Helm 22, Curran, right behind her in the sequence. Dark-haired, like enough for a brother; and close to that “I heard that from Ma’am.”

“I hope.” She folded her arms, gathered up her cheerfulness. “I had an offer, I want you to know. My friend last night was looking for crew. Number one and only on his own ship, he said. Offered me a Helm 2 chair, he did. At least that’s what I think he was offering.”

Curran chuckled. It was worth a laugh, a marginer making offers to Dublin. And not so deep a laugh, because it touched hopes too sensitive, that they both shared.

“Cousin Allie.” That shrill piping was aged four, and barrelled into her unbraced lap, to be picked up and bounced. Allison caught her breath, hauled Tish up on her leg, bounced her once dutifully and passed her with a toss over to Curran, who hugged the imp and rolled her off his lap onto the empty cushion beside him. “Going to go,” Tish said, having, at four, gotten the routine down pat. “Going to walk all round Dublin.”

“Pretty soon,” Curran said.

“Live up there” Tish said, jabbing a fat finger ceilingward. “My baby up there.”

“Next time you remember to bring your baby down,” Allison said. “You bring her with you the next time we dock.”

There had been no end of the wail over the forgotten doll at the start of their liberty. Middle zones of the ship went inaccessible during dock; and young Will III had offered to eel through the emergency accesses after it, but no, it was a lark for Will, but a good way to take a fall, and Tish learned to keep track of things. Everyone learned. Early.

“Go,” Tish crowed, anxious. Prolonged dock was no fun for the littlest, in cramped spaces and adult noise.

“Bye,” Allison said, and Tish slid down and worked her way through adult legs to bedevil some of her other several hundred cousins, while Allison shut her eyes and wished the noise would stop. Her wishes were narrow at the moment, centered on her own comfortable, clean-smelling bed.

Then the bell rang, the Cinderella stroke that ended liberty and liberties, and the children were shushed and taken in arms. Conversations died. People remembered hangovers and feet and knees that ached from walking unaccustomed distances on the docks, recalled debts run up that would have to be worked off oddjobbing. “I lied,” someone said louder than other voices, the old joke, admitting that after-the-bell accounts were always less colorful. There was laughter, not at the old joke, but because it was old and comfortable and everyone knew it. They drifted for the cushions, and there was a general snapping and clicking of belts, a gentle murmur, a last fretting of children. Allison bestirred herself to pull her belt out of the housings and to clip it as Eilis settled into the seat next to hers and did the same.

Bacchanale was done. The Old Man was back in the chair again, and the posted crew, having put down their authority for the stay on station, took it up again.

Dublin prepared to get underway.

Chapter III

Lucy was never silent in her operation. She had her fan noises and her pings and her pops and crashes as some compressor cycled in or a pump went on or off. Her seating creaked and her rotation rumbled and grumbled around the core… a rotating ring with a long null G center and belly that was her holds, a stubby set of generation vanes stretched out on top and ventral sides: that was the shape of her. She moved along under insystem propulsion, doing her no-cargo best, toward the Viking jump range, outbound, on the assigned lane a small ship had to use.

Sandor reached and put the interior lights on, and Lucy’s surroundings acquired some cheer and new dimensions. Rightward, the corridor to the cabins glared with what had once been white tiles—bare conduits painted white like the walls; and to the left another corridor horizoned up the curve, lined with cabinets and parts storage. Aft of the bridge and beyond the shallowest of arches, another space showed, reflected in the idle screens of vacant stations, bunks in brown, worn plastic, twelve of them, that could be set manually for the pitch at dock. Their commonroom, that had been. Their indock sleeping area, living quarters, wardroom—whatever the need of the moment. He set Lucy’s autopilot, unbelted and eased himself out of the cushion: that was enough to get himself a stiff fine if station caught him at it, moving through the vicinity of a station with no one at controls.

He found the pulser unit in under the counter storage, taped it to his wrist and handed himself across the bridge, fighting the spiral drift along to the right-hand corridor, a controlled stagger with right foot on the tiled footing curve and left on the deck. He got the Pharmaceuticals he wanted and brought them back to his place on the bridge, another stagger down the footings and swing along the hand grips. Then he knelt down in the pit and used tape and braces to rig her as she had been rigged before, taped the drugs he would need for jump to the side of the armrest where he could get at them; taped down some of the safety controls—also illegal; he set up the rig for the sanitation kit, because he would need that too, much as he dreaded it.

A second trip, rightward, this time, past sealed cabins, into the narrow confines of the galley and galley storage. He filled water bottles, and took an armful of them back to the bridge, jammed them into the brace he had long ago rigged near the command console… scared, if he let himself think about it. He swallowed such feelings, bobbed his head up now and again to check scan, down again to open up the underdeck storage where he had shoved some of the dried goods, not to have to suit up for the chill of the holds to hunt for them. He knelt there counting the packets out, taped them where he could get at them from the chair. His braced limbs shook from the strain of G. He dropped a packet and lunged after it, taped it where it belonged.

The lane still showed clear. He crawled up and held onto the back of the cushion, staring at the instruments, finally edged his way back to one of the brown plastic bunks at the aft bulkhead, to give his back a little relief from the strain. His eyes stung with fatigue. He rested his hands beside him, arms pulled askew by the spiral stress of acceleration, leaned his head against the bulkhead, not really comfortable, but it was a change from the long-held position in the cushion, and he could get the com or the controls from here if he had to.

There were compartments all about the ring, private quarters. Diametrically opposite the bridge was the loft, where the children had been… he never went around the ring that far. This was home, this small space, these bunks aft of the bridge, plastic mattresses patched with tape and deteriorating with age. One had been his when he was ten, that over there, nearest lie partition spinward; and there had been Papa Lou’s, which he never sat on; and one his mother’s; he had had brothers and sisters and cousins once, and there had been three children under six, cousins too. But Papa Lou had vented them and old Ma’am too, when their boarders turned ugly and it was clear what they were going to do.

They had had Lucy’s armament, but that had been helpless against a carrier and its riderships; they had had only two handguns on the ship… and the boarders who had ambushed them in the nullpoint had said they were not touching crew, only cargo. It had been Lucy’s clear choice then, open the hatch or be blown entirely. But they lied, the Mazianni, pirates even then, in the years when they had called themselves the Company Fleet and fought for Pell and Earth. They respected nothing and counted life nothing, and into such hands Papa Lou had surrendered them… not understanding.

He himself had not understood. He had not imagined. He had looked at the armored, faceless invaders with a kind of awe, a child’s respect of such power. He had—for that first few moments they had been aboard—wanted to be one of them, wanted to carry weapons and to wear such sleek, frightening armor—one brief, ugly temptation, until he had seen Papa Lou afraid, and begun to suspect that something evil had come, something far less beautiful inside the armor, that had gotten into the ship’s heart. He always felt guilt when he recalled that… that he had admired, that he had wanted to frighten others and not be frightened—he reasoned with himself that it was only the glitter that had drawn him, and that any child would have reacted the same, in the confusion, in the shaking of reliable references, in ignorance, if not in innocence. But he always felt unclean.

Most of it had happened here, on the bridge, in the commonroom and the corridor, in this widest part of the ship where they had gathered everyone but the children, and where the boarders started showing what they meant to do. But Papa Lou had gotten to the command chair and voided the part of the ship where the children and the oldest had taken refuge, before they shot him; and most of them had died, shot down in the commonroom and on the bridge; and some of them had been taken away for slower treatment.

But three of them, himself and old Mitri and Cousin Ross, had lain there in the blood and the confusion because they were half dead—himself aged ten and standing with crew because he had slipped around the curve and gotten to his mother’s side. They had not died, they three, which was Ross’s doing, because Ross was mad-stubborn to live, and because after they had been left adrift, Ross had dragged himself from beside the bunk where he had fallen on him and Mitri, and gotten the med kit that was spilled all over where the pirates had rifled it for drugs. That was where his mother had been lying shot through the head: he recalled that all too vividly. She had gotten one of the boarders at the last, because they had given the women the two guns—they needed them most, Papa Lou had said—and when Papa Lou vented the children his mother had shot one of the boarders before they shot her, got an armored man right in the faceplate and killed him, and they dragged him off with them when they left the ship, probably because they wanted the armor back. But Aunt Jame had died before she could get a clear shot at any of them.

Here they had fallen, here, here, here, twelve bodies, and more in the corridor rightward, and himself and Mitri and Ross.

Those were his memories at times like this, fatigued and mind-numbed, or cooking a solitary meal in the galley, or walking past vacant cabins, sights that washed out all the happier past, everything that had been good, behind one red-running image. Everywhere he walked and sat and slept, someone had died. They had scrubbed away all the blood and made the plastic benches and the tiles and the plating clean again; and they had vented their dead at that lonely nullpoint, undisturbed once the pirate had gone its way—sent them out in space where they probably still drifted, frozen solid and lost in infinity, about the cinder of an almost-star. It was a clean, decent disposal, after the ugliness that had gone before. In his mind they still existed in that limbo, never decayed, never changed… they went on traveling, no suit between them and space, all the starry sights they had loved passing continually in front of their open, frozen eyes—a company of travelers that would stay more or less together, wherever they were going. All of them. Only Ma’am and the babies had gone ahead, and the others would never overtake them.

Mitri had died out on the hull one of the times they had had to change Lucy’s name, when they had run the scam on Pan-paris, and it had gone sour—a stupid accident that had happened because the Mazianni had stripped them of equipment they needed. Ross had spent four hours and risked his life getting Mitri back because they had thought there was hope; but Mitri had been dead from the first few moments, the pressure in the suit having gone and blood having gotten into the filters, so Ross just called to say so and stripped the suit and let Mitri go, another of Lucy’s drifters, but all alone this time. And he, twelve, had sat alone in the ship shivering, sick with fear that something would happen to

Ross, that he would not get back, that he would die, getting Mitri in.

Leave him, he had yelled at Ross, his own cowardice, before he had even known that Mitri was dead; he remembered that; and remembered the lonely sound of Ross crying into the mike when he knew. He had thrown up from fright after Ross had come in safe. Another lonely nullpoint, those points of mass between the burning stars that jumpships used to steer by; and he could not have gotten Lucy out of there, could not have handled the jump on his own, if he had lost Ross then. He had cried, after that, and Mitri had haunted him, a shape that tumbled through his dreams, the only one of Lucy’s ghosts that reproached him.

Ross had died on Wyatt’s, dealing with people who tried to cheat him. The stationers, beyond doubt, had cremated him, so one of them was forever missing from the tally of drifters in the deep. In a way, that troubled him most of all, that he had had to leave Ross in the hands of strangers, to be destroyed down to his elements… but he had had only the quick chance to break Lucy away, to get her out before they attached her, and he kept her. He had been seventeen then, and knew the contacts and the ports and how to talk to customs agents.

He slept in Ross’s old bunk, in this one, because it was as close as he could come to what he had left of family, and this one bed seemed warmer than the rest, not so unhappily haunted as the rest. Ross had always been closer than his own mind to him, and because he had not cast out Ross’s body with his own hands, it was less sometimes like Ross was dead than that he had gone invisible after the mishap at Wyatt’s, and still existed aboard, in the programs comp held—so, so meticulously Ross had recorded all that he knew, programed every operation, left instructions for every eventuality… in case, Ross had said, simply in case. The recorded alarms spoke in Ross’s tones; the time signals did; and the instruction. It was company, of sorts. It filled the silences.

He tried not to talk to the voice more than need be, seldom spoke at all while he was on the ship, because he reckoned that the day he started talking back and forth with comp, he was in deep trouble.

Only this time he sat with his eyes fixed on the screens on the bridge, with his shoulder braced against the acceleration, and a vast lethargy settled over him in the company of his ghosts. Ross, he thought, Ross… I might love her; because Ross was the closest thing he had ever had to a father, a personal father, and he had to try out the thought on someone, just to see if it sounded reasonable.

It did not. There were story-tapes, a few aged tapes Ross had conned on Pan-paris when they were young and full of chances. He listened to them over and over and conjured women in his mind, but he knew truth from fancy and refused to let fancy take a grip on him. It had to do with living… and solitude; and there were slippages he could not afford. He had been drunk, that was all; was sober now, and simply tired.

He had been crazy into the bargain, to have paid what he had paid to get clear of station. And he was outbound, accelerating, committed… He was headed for a real place out there, was about to violate lane instructions, headed out to new territory with forged papers. It was a real place, and a real meeting, where a dream could get badly bent.

Where it could end. Forever.

(Ross… I’m scared.)

No noise but the fans and the turning of the core, that everpresent white sound in which the rest of the silence was overwhelming. Little human sounds like breathing, like the dropping of a stylus, the pushing of a button, were whited out, swallowed, made null.

(Ross… this may be the last trip. I’m sorry. I’m tired…)

That was the crux of it. The certainty settled into his bones. The last trip, the last time—because he had run out of civilized stations Unionside. Even Pell, across the Line—they had called at once, when it was himself and Ross and Mitri together; and Lucy had been Rose. They owed money there too, as everywhere. Lucy was out of havens; and he was out of answers, tired of fear, tired of starving and sleeping the way he had slept on the way into Viking, marginally afraid that the old man he had hired might rob him or get past the comp lock or—it was always possible—kill him in his sleep. And once, just once to see what others had, what life was like outside that terror, with the fancy bars and the fancy sleepovers and a woman with something other than larceny in mind—

He had never had a place to go before, never had a destination. He had lived in this narrow compartment most of his life and only planned what he would do to avoid the traps behind him. Pell, Allison Reilly said; and deals; and it agreed with the rumors, that there were routes opening, hope—hope for marginers like him.

It was a joke of course, the best joke of a humorous career. A surprise for Allison Reilly—she would turn and stare open-mouthed when he tapped her on the shoulder in some crowded Pell Station bar. He knew what Lucy could do, and what he could do that great, modern ship of hers would never try—

Stupid, she would say. That was so. But she would always think about it, that a little ship had run jump for jump against Dublin Again. And that was something of a mark to make in his life, if nothing else. There was, in a sense, more of Lucy left than there was of him… because there was no end to the traveling and no end to the demands she made on him. He had given all he had to keep her going; and now he wanted something out of her, for his pride. He had no Name left; Lucy had none. So he did this crazy thing—in its place.

He shut his eyes, yielded to that G that pressed him uncomfortably against the bulkhead, drowsing while he could. The pulser was taped to his wrist so that the first beep from the outrange buoy would bring him out of it. Station would have his head on a plate if they knew; but it was all the chance he had to go into jump with a little rest.

The pulser stung his wrist, brought him out of it when it only felt as if he had fallen asleep for a second. He lurched in blind fright for the controls and sat down and realized it was only the initial contact of the jump range buoy, and engine shutdown, on schedule.

Number one for jump, it told him; and advised him that there was another ship behind. A chill went up his back when he reckoned its bulk and its speed and the time. That was Dublin, outbound, overtaking him much more slowly, he suspected, than it could, because of their order of departure—because Lucy, ordinarily low priority, was close enough to the mark now that Dublin was compelled to hang back off her tail. The automated buoy was going to give them clearance one on the tail of the other because the buoy’s information, transmitted from station central, indicated they were not going out in the same direction.

And that was wrong.

He checked his calculations, rechecked and triple-checked, lining everything up for an operation far more ticklish than calculating around the aberrations of Lucy’s docking jets. Nullpoints moved, being more than planet-sized mass, in the complicated motions of stars. Comp had to allow for that. No one sane would head into jump alone, with a comp that had no backup, with trank and food and water taped to the board: he told himself so, making his prep, darting glances back to comp and scan, listening to the buoy beeping steadily, watching them track right down the line. He put the trank into his arm. It was time for that… to dull the senses which were about to be abused. Not one jump to face… but three; and if he missed on one of them, he reckoned, he would never know it.

There was speculation as to what it was to be strung out in the between, and speculation about what the human mind might start doing once the drugs wore off and there was no way back. There were tales of ships which wafted in and out of jump like ghosts with eerie wails on the receiving com, damned souls that never came down and never made port and never died, in time that never ended… but those were drunken fancies, the kind of legends which wandered station docksides when crews were topping one another with pints and horror tales, deliberately frightening stationers and insystem spacers, who believed every word of such things.

He did not, above all, want to think of them now. He had little enough time to do anything hereafter but keep Lucy tracking and keep his wits about him if things went wrong. If he made the smallest error in calculation he could spend a great deal of time at the first nullpoint getting himself sorted out, and he could lose Dublin. The transit, empty as he was, would use up a month or more subjective time; and Dublin would shave that… would laze her way across the space of each nullpoint, maybe several days, maybe a week resting up, and head out again. Lucy did not have such leisure. He had no plans to dump all velocity where he was going, could not do that and hope to outpace Dublin’s deeper stitches into the between.

The trank was taking hold. He thought of Dublin behind him, and the hazard of it. He reached for the com, punched it in, narrow-focused the transmission, a matter between himself and that sleek huge merchanter that came on his tail. “Dublin Again, this is US 48-335 Y Lucy, number one for jump. Advise you the buoy is in error. I’m bound for Pell. Repeat, buoy information is in error; I’m bound for Pell: don’t crowd my departure.”