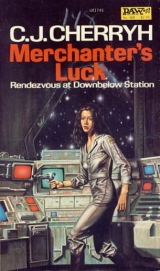

Текст книги "Merchanter's Luck "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Chapter V

He woke, aware of bare smooth skin next to his own, of a warm arm about him, and turned, blinked in confusion. She was still here, in the room’s artificial twilight. “Allison,” he said hoarsely, hoarse because his voice like the rest of him was not in the best of form. He stroked her hair and woke her without really meaning to ruin her sleep.

“Huh,” she said, looking up at him. “About time.” But when he tried with her, there was nothing he could do. He lay there in wretched embarrassment and thinking that at this point she would probably get up and get dressed and walk out of his life forever, about the time he had just spent most of it.

“What could you expect?” she said, and patted his face and took his hand and carried it against her mouth, all of which so bewildered him that he simply lay there staring into her eyes and expecting her to follow that statement with something direly cutting.

She did not. “I’m sorry,” he said finally. I’m really sorry.”

“There’s tomorrow. A few more days. What are you going to do, Stevens? Is it worth the handful of days you bought with this stunt?”

He thought about it. For a moment he found it even hard to breathe. It really deserved laughing about, the whole situation, because there was something funny in it. He managed at least to shrug. “So, well, maybe. But I think I’m done after this, Reilly. I don’t think I can do it again.”

“You’re absolutely out of your mind.”

He found a grin possible, which at least kept up his image. “I don’t make a habit of it.”

“Why’d you do it?”

“Why not?”

She frowned. Scowled. She shook her head after a moment, got up on her elbow, looking down at him, traced the old scar on his side, a gentle touch. “What are you going to tell your company?”

He lay there, stared at the ceiling with his head on his arms, considered the question and truth and lies, grinned finally and shrugged with what he hoped was monumental unconcern. “I don’t know. I’ll think of something good.”

A fist landed on his ribs. ‘I’ll bet you will. No cargo. No clearance. You jumped out of Viking on the wrong heading. What are they going to do to you, Stevens?”

“Actually,” he said, “it’s a minor problem.” He shut his eyes, still with a smile painted on his face and a weariness sitting on his chest that seemed the accumulation of years. “I’ll talk my way out of it, never fear.” And after a moment: “Why don’t we try it again, Reilly? I think it might work.”

It did, oddly enough—and that, he thought, lying there with Allison Reilly tangled with him and content, was because he had started thinking again how to con his way through, and about saving his skin and Lucy’s, which got his blood moving again, however tired and sore he was. He was remarkably placid in contemplating his ruin, which he figured he could at least postpone until Allison Reilly had put out of Pell Station aboard Dublin some few days hence. And there was the gold: he had that. If by some miracle no one had known his face, he might get himself papers, get himself cargo—go back to Voyager without routing through Viking, a chancy set of jumps, then come in with appropriate stamps on his papers to satisfy Viking—if Dublin had not reported that message about his change of destination…

He could find out. Allison might know. Would tell him. And maybe, the irrepressible thought occurred to him, he could claim some tie to Dublin for the benefit of Pell authorities, use that supposed connection for a reference, at least enough for dock charges. She might do it for him. He thought of that, lying there with her arms about him, in a bed she had paid for, that he might work one remarkable scam and get himself a stake charged to Dublin’s account, which would solve all his problems but Viking and, with the gold, get him a real set of papers.

He turned his head and looked at her, into eyes which suddenly opened, dark and deep and warm at the moment; and his gut knotted up at what he was thinking to do, which was to beg; or to cheat her; and neither was palatable. She hugged him close and he fell to kissing her, which was another pleasure he had discovered different with Allison Reilly.

It was hardly fair, he thought, that he himself had fallen into such hands as Allison’s, who could con him in ways he had never visited on his most deserving victims. She was having herself a good time, not even maliciously, while he was paying all he had for it.

And it was finished if she knew, in all senses. She might not, even then, turn him in; but she would know… and hate him; and that was, at the moment, as bad as station police.

“Actually,” he said during a lull, “actually I’ll tell you the truth. I’m not in trouble. It’s all covered, my shifting to Pell.”

“Oh?” She stiffened, leaned back and looked at him. “How?”

“Because I’ve got an account to shift here. I’m a small enough operator the combine gives me quite a bit of leeway. All they ask is that I make a profit for them. They let me come and go where I can do that. Wyatt’s can’t be figuring down to the last degree where to have me break off an operation: that’s my decision to make. You made Pell sound good. I heard the rumors. And you just tipped the balance.”

“Huh.” There was a sober look on her face. “Not me at all, was it?”

“I could have taken my time getting here. I wanted to see you. That part’s so.”

The sober look became a thinking look, a different, colder one. “Well, then, I guess you will get out of it all, won’t you?”

“I will. No question.”

“Huh,” she said again. She rolled for the edge of the bed and he caught her wrist, stopping her.

“Where are you going?”

“Can’t stay any longer. I have duty.”

“What did I say?”

“You didn’t say anything. I just have my watch coming up.”

“It was something. What was it?”

Her face grew distressed. She jerked at his hand without success. “Let go.”

“Not until you tell me what I said.”

“If you put a mark on me, Stevens, you’ll regret it You want to think that through?”

“I’m trying to talk to you. I told you the truth.”

“I don’t think you know the truth from your backside. You didn’t tell me the truth and I’ll bet you didn’t tell it to customs out there.”

His heart slammed against his ribs, harder and harder. “So does Dublin tell the whole truth to customs? Don’t ask me to believe that”

“Sure. I figure there are all kinds of reasons someone would give me one story and customs another; but maybe only one reason a ship would dog us the way you have, and I don’t like the smell of it. You never have answered me straight, not once, and I gave you your chance. Now maybe you can break my arm and maybe you even figure you can kill me to shut me up, but, mister, I’ve got several hundred cousins who know who I’m with and where and you’ll find yourself taking a slow voyage on Dublin if you don’t let me out of here right quick.”

“Is that why you stayed? To ask questions?”

“What do you expect?”

He stared at her with more pain than he had felt since Ross died, let go her arm so suddenly she almost rolled off her edge of the bed; and she sat there rubbing her wrist and glaring at him. He had no wish to be looked at. “Go on,” he said. “I’m not stopping you.”

“Don’t tell me I’ve hurt your feelings.”

“Impossible. Go on, get out of here and let me sleep.”

“It’s my room. I paid the bill.”

That hurt I’ll take care of it I’ll put the fifty in Dublin’s account. And the fifty before that. Just take yourself off. No worry about the cash.”

“It really looks like it. What are you doing, following us to get me to pay your bar bills? You going to hit me up for finance?”

“I don’t charge,” he said bitterly. His face burned. “Go on. Out.”

She stood up, stalked over, collected her clothes from the chair and started pulling them on—paused, sealing up the silver coveralls, and looked back at him.

“Probably I’d better pay your rent for the week,” she said. “I think you’ve got troubles, Stevens. I think your combine’s going to have your head on a platter. You’re not going to turn a profit on this.”

“Don’t bother yourself. I don’t want your money and I don’t want your help. I’ll handle my combine.”

“Oh, sure, you’re going to explain how it all seemed a good idea at the time. This story’s going to be told over and over again, bigger every time it hits another station. How you did it to see me again, how you did it for a bet, how you took out of Viking the wrong direction and triplejumped solo through Tripoint, that you’re a Mazianni spotter or a Union spy with a hyped-up ship or an outright thief, and you know how much Dublin wants herself mixed into the story? The tale’ll get back to Viking without our help. They’ll hear it on Wyatt’s real early; they’ll hear it everywhere ships go… because they’re all here, every ship, every family, every Name in the Merchanter’s Alliance and then some. And Union military’s coming in to call. It’s going to spread. You understand that?”

He thought about that, with a chill feeling in his stomach. “So, well, then, it looks like I’ve got a bigger problem than you do, don’t I? I’m sure Dublin’s going to survive it”

“Bastard.”

“You came out on the dock, Reilly. That was your doing. I didn’t arrange it.”

“I’ve no doubt you’d have come to Dublin asking for me. You used our name over com. What more did it lack?”

“Out.”

“You’re flat broke, Stevens. Unless you’re carrying something under the plates. And they’ll look. You’re going to get your ship attached. At the least”

“I’ve got funds.”

“What have you got?”

“Maybe it’s none of your business.”

“You don’t. Not worth this trip.”

“None of your business.”

“Huh.”

He stared at her, unwilling to fight it out. Watched her walk to the door—and stop. She stood there. Looked back finally, dropping her hand from the door switch. “You tell me,” she said, “really why you pulled this.”

“Like you said.”

“Which?”

“Take your pick. I’m not going to argue the point.”

“No. You tell me, Stevens, how you’re going to rig this. I really want to know.”

He shrugged, sitting up, hooked his arm in the pillows and propped himself against the headboard. “I told you already what I’m going to do. It’s no problem.”

“I think you’re in bad trouble.”

“Nothing I can’t solve.”

“So I’m flattered I made such an impression on you. But I’m not why you came. What made you?”

He tried a wry smile, reckoning he could hold it. “Well, it seemed reasonable at the time.”

“I keep wanting to believe you. And I’m not getting any encouragement.”

“I’m used to running solo,” he said in a lingering silence. “It’s no big deal. I’ve jumped her alone and I’ve twojumped. She’s good, Lucy is. She kept up with your fancy Dublin, for sure. I’ll tidy it up with WSC when I get back to Viking. I wouldn’t mind seeing you, when.”

She came back and sat down on the edge of the bed, leaned with her hand on his and looked into his face at too close an interval for comfortable pretenses. “Possibly,” she said, “you can claim fatigue and they’ll let you out of this. Maybe it was just being out there too long.”

“Thanks. I hadn’t thought of that one. I’ll try it.”

“I’d guess you’d better try something. You are in trouble. Aren’t you?”

He said nothing.

“Stevens. If it is Stevens… How much truth have you told me? At any time?”

“Some.”

“About what you are—how about that, for a start?”

He tried to shrug, which was not easy at close quarters. “I’m what I told you.”

“You’re broke, aren’t you? And in a lot of trouble. I think maybe you thought I could finance you. I think maybe that’s what this is all about, that you really did come chasing after me– because you’ve overrun your margin at Viking, haven’t you; and maybe your company’s going to be asking questions—and now you’ve got a combine ship where she doesn’t belong.”

“No.”

“No?”

“I said no.”

“You know, Stevens, I shouldn’t ask this, but it does occur to me that you just may not be combine.”

He stared at her, at a frown which was not anger, his hold on his silence loosened for no good reason, but that she knew—he knew that she knew. She was headed back to her ship, to talk there, for certain.

“Not, are you?”

“No. I’m not. I’m—” His arm went out to stop her from bolting, but that shift had not been to get up, and he was left embarrassed. “Look, WSC never noticed me. I made them money. I never cost them a credit…”

“Before now.”

“I’ll put it back.”

“You are a pirate.”

“No.”

“All right. So I wouldn’t sit here if I thought that. So you skim. I’m not sure I want to know the details.” She heaved a sigh and turned to sit sideways on the bed, slammed her fist into her knee. “Blast.”

“What’s that?”

“That’s wishing I minded my own business. So I know. So I can’t do anything about it. I’m not going to. You understand that? It’s worth no money to you, whatever you planned to get.”

Heat rose to his face. “No. I’ll tell you the truth: it was getting tight there. Really tight. So you made me think of Pell, that’s all. I figure maybe I’ve got a chance here.”

“Just like that.”

“Just like that. That’s when I know to move. I feel the currents move and I go. It keeps me alive.”

She stood up, thinking about the law: there was that kind of look on her face. Thinking about conscience, one way and the other. About police.

“I’ll tell you,” he said, and rolled over on his side, searching for his clothes. He located them on the floor and sat up, swung his feet out of bed to dress. “Reilly—I don’t like it to go sour like this. I swear to you—any way you like—I know you’re worried about it. I don’t blame you. But that ship’s mine. And that’s the truth.”

“I don’t want to listen to this. I’m Helm, you hear me, and I keep my hands clean. We’ve got our Name, and I swear to you, mister, you crowd me and I’ll protect it. I’m sorry for you. And I’ll believe what you’ve told me in the hope that once a day you do tell the truth, and that I don’t need to pass the word about you on the docks, but I don’t think I want to hear any more about it than I have. And I don’t think I’ll be meeting you elsewhere. I don’t think you’d better plan on that.”

“You wait a minute. Just wait a minute.” He pulled his clothes on, caught at disadvantage, zipped the plain coveralls and caught his breath and his dignity. “Listen—I’m sorry about that mess on the docks. It was crazy. I never—never intended that I didn’t expect them to be crazy here.”

Pell Operations is always on vid.—You didn’t know that. You know how you sounded, coming in? Like a crazy man. Like someone crazy aiming a ship at the station; and then like somebody in trouble… it was on the news channel, and thousands of people were punching in on it. Misery, Stevens, it’s Pell. Alliance captains are coming in here, big Names, flash ships… Finity’s End and Little Bear, one after the other. Winifred. Pell folk know the Names. And some of these free souls don’t take to regulations and some of them have privilege with a capital P. When something comes in like you came—they appreciate style, these Pell stationers. And being stationers they’re just a little ignorant about what a stupid move you pulled and what dice you really shot out there at Tripoint You’ve got a death wish, Stevens. Deep down somewhere, you’re self-destructive; and you scare me. You’re trouble. To me. To yourself. To a system full of ships and a station full of innocent people who had the good-heartedness to worry about you after they realized you weren’t going to hit them. They think you did it on skill. On dockside they think something else. They think you’re an ass, Stevens, and I’m embarrassed for you, but I got you in here because I was stuck with you after that scene on the docks; because you at least had the conscience to warn Dublin when you risked our lives at Viking, and my Old Man called me in on the carpet and looked me right in the eye and asked me what you were. When this liberty’s over or before, I’m going to have to go on the carpet again and answer why I got Dublin involved with you. And I still don’t know.”

He stood and took it. It was the truth. It was all the things that had shivered down his backbone when he came in. “I’ve done the like before,” he said in a quiet voice. “I told you that Sometimes I’ve had to do it I’ve had no choice. I came in high in the range. But I miscalculated myself, not the ship; too long on the dock at Viking, too little sleep, too little food—I wasn’t fit for it; that, I admit to. But the solo runs—Lucy’s not Dublin. I bend the regulations. That’s how someone like me has to operate. You’ve got to sleep; you do it on auto, wherever you are. You’re redlighting and you’ve got to see to it; and you run on auto. And you have to know that, even on Dublin, you have to know that all those marginers like me, we’re running like that. It’s not neat and failsafed. I thought I could do it. And I did it on luck at the end, and I should have let you pass me at Viking. I wanted out of there. If I’d delayed my run when I had a clearance—there were questions possible. And I went, that’s all.”

“And the interest in Dublin?’’

He shrugged, arms folded.

“You make me nervous,” she said.

“You. I wanted to see you.”

She shook her head uneasily. “Most can wait for that privilege.”

“Some don’t have that much time.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

A second shrug, less and less comfortable. “I don’t stay in one place very long. And I’ll be gone again. I’ll stay low till you go. I think that’s about the best thing I can do under the circumstances. When you pull out, I’ll set about getting myself out of this. But no mention of Dublin. I promise that.”

She stared at him sidelong, a good moment. “I’m not posted. You understand—my getting involved here—can keep me from being posted. Ever. It’s not a lark, Stevens. It was.” She walked to the door, looked back. “I’ve got maybe ten thousand I can lay my hands on. I can maybe keep you clean here, if you take that and pay your dock charge and clear out of Pell. Understand me, it’s all I can get. I’ll be another year working off the last thousand of it But I want you off Dublin’s record. I don’t want you in trouble again until somewhere a long, long way off our trail.”

He shook his head, his mouth gone dry. He hurt inside.

“Blast you, there’s nothing more you can get.”

“I don’t want your money. I don’t want your help. I’ll take out of here. I can pay the dock charges, and I’ll take out.”

“With what?”

“That three thousand. Maybe I can get a little cargo on the side. I’ve got, well, maybe a little more than that.”

“How much worth of cargo?”

That’s my business. You answer questions to strangers about Dublin’s holds? I’d think not.”

She set her jaw. “I want you out of here.”

“Tell your Old Man I’m going.”

“I’ll tell you you’re taking the ten thousand. You’re going out of Pell with some kind of a load, mine and yours together, that at least looks honest And you forget the debt. Don’t try to pay it. Don’t talk about it. Or me. Or I go to station authorities.”

“I understand you,” he said very quietly. “I’d take your ten. And I’d promise to get it back to you, but I don’t think you’d believe it. And it wouldn’t be the truth. You’re throwing it away, Reilly. I very much doubt I’m going to clear this dock at all.”

“Someone here you know?”

“More than likely someone here that knows me. It’s the publicity, Reilly. I’m usually a lot quieter.”

“What,” she asked in a lowered voice, “can they get you for? What’s the worst?”

“Bad debts.”

“Less than likely any merchanter would go to the police on that score. But something else—”

“I’m not one of the Names. They don’t know what I might be. A pirate. They could think that. But I’ll tell you the whole truth this time. I’ve got two thousand cash I’m not declaring. For dock-side deals.—And fourteen thousand worth of WSC money in gold under the plates. That’s why I ran out of Viking like my tail was afire.—Look, this stationer there, this clerk—I had to deal; he could have blown it all. It wasn’t my idea. So I have the money. I can pay dock charges and I can deal for cargo.”

“With sixteen lousy contraband thousand?”

“You think ten more is going to help? No. And if they catch me, you can believe they’re going to inventory everything I’ve got; and they’d find me with more scrip than I’m supposed to have; and ten thousand in Pell currency, right? One question to comp and they’d have those serial numbers and a ten thousand transaction in your name. Take it from me. I know the routines.”

“I’ll bet you do.”

“So you keep it. Against my problems, it’s nothing, that ten. I’ll get out of it my way.” He picked up his jacket and put it on, checked his papers in his pocket. “I’ll go take care of the finance, go to station offices. You just call it quits and go hang out with your cousins and say it’s all nothing. Find somebody else to sleep-over with and publicize it, fast. That’ll kill it I know how to cover a trail. That, too.”

“I wish you luck,” she said, sounding earnest. “You’ll need it”

He opened the door for her. Grinned, recovering himself. Thanks,” he said, and walked out, ahead of her in the hall, hands in pockets, a deliberate spring in his step.

Time to visit Lucy. Time to go under the eyes of the powers that be on Pell and try to pull it out of the fire. Or at least get some of the heat off. Station offices would unseal her for him if he could eel his way past a customs agent who might want to do a thorough check in his presence.

Then to get out of Pell with as much cash as he could save. Maybe check the black market—there was always that. Change the name and number out at Tripoint, trade black market at the nullpoints and hope no one cut his throat. Buy another set of forged papers. If he could get out with money; and if… a thousand things. His mind began to work again more clearly, with Allison Reilly set behind him. With bleak realities plain on the table.

He looked back. She was there, at the door of the sleepover, just watching. A craziness had come on him for a time. Self-destructive: she was right. On the one hand he wanted to survive; and on the other he was tired of trying, and it was harder and harder to think his way through the maze… even to recall what lies he had told and how they meshed.

There were troops here too. He saw them… a jolt. Not the green or the black of Union forces, but blue. Alliance militia. He recalled the buildup at Viking and the rumors of pirate-hunting and had a presentiment of times changing, of loopholes within which it had been possible for marginers to survive—being tightened, suddenly, and with finality.

He had a record at every station in Union now; and soon a record with the Alliance; and he was almost out of places.

“What happened?” Curran asked, joining her in the shadow of the sleepover doorway, and Allison frowned at the intrusion. “Been there,” Curran said with a nod toward the bar next door. “Some of us had a little concern for it… hung around. In case. What’s he up to? You know the Old Man’s going to ask.”

“He’s going back to his ship. I’m afraid it’s a case of misplaced assumptions. We’re quits.”

“Allie, they’ve got a guard out there.”

She straightened, dropped her arms from their fold. “What guard?”

“On his ship. That’s what’s had us upset. We weren’t about to break in on you, but we’ve sure been thinking. That’s military, that.”

She hissed between her teeth, “More than customs seal?”

“More than customs. They say one of Mallory’s officers is on station.”

“I heard that.”

“Allie, if they haul him in, is there anything he can say he shouldn’t?”

“No.” She turned a scowl on her cousin, sharp and quick. “Are you making assumptions, Currie me lad? Don’t Allie me.”

“When our watch senior sleeps over with a man the militia’s got their name on… we come asking questions. Third Helm has a stake here.”

“You don’t oversee me.”

“That’s thanks.—We’ve backed you. Get back to the ship. We’re asking. Now.”

She said nothing. Followed the distant figure with her eyes. There was not so much traffic now as mainday. A new set of residents had come out to work and trade in the second half of Pell’s nevernight—more industrial traffic than in mainday; passersby wore coveralls more than suits, and traffic on the docks was heavy moving, big mobile sleds hauling canisters, whining their way along through a straggle of partying merchanters.

And troops.

And others. Pell orbited a living world. Natives worked on the station, small and furtive, wearing breather-masks that hissed when they breathed. They were brown-furred and primate… moved softly on callused bare feet. And watched, two of them perched on the canisters stacked nearest Lucy’s dock. She made out another of them near the security rail. They moved suddenly, took themselves elsewhere, a vanishing of shadows.

She shook her head slowly, took Curran by the arm and saw the rest of her watch standing by, Deirdre and Neill. “Back,” she said.

“He got a gun?”

“No,” she said. “That, I know for sure. But we’ve no need to be bystanders, do we?”