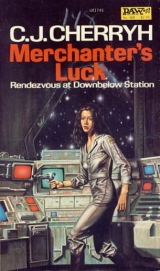

Текст книги "Merchanter's Luck "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

*Understood. A moment more he lingered, knowing then that something was on her mind. She gave a jerk of her head toward the galleyward corridor. *Out, she meant; and he went.

Watch to watch: it was the tail of her second, 1442, when Neill came wandering out of the cabins corridor, shaved and combed and fresh-looking. Deirdre followed, pale and sober, looked silently at Stevens sleeping there. *All right? The uplifted thumb. It was a question.

Allison nodded, and they padded back again, to the little personal time they had in their schedules. She had the ship on auto, their escort running placidly beside them. She watched Curran at his meddling with the comp console, quiet figuring and notetaking. There was not a chance he could crack it. Not a chance.

A bell went off, loud and sudden, down the corridors the way Neill and Deirdre had gone. She looked up, a sudden clenching of her heart, at the blink of a red light on the lifesupport board. The bell and the light stopped. The section seal had opened, closed again. “Deirdre,” Curran was saying into com. “Neill. Report.”

A weight hit Allison’s cushion, Stevens leaning there. “Section seal’s opened,” she said. “Are they all right, Stevens?”

“No danger, none.”

She believed it when Neill’s voice came through. “Sorry. We seem to have tripped something.”

Exploring the ship. Trying to do the logical thing, going around the rim. “You all right?” Curran asked.

“Just frosted. Nothing more. Section three’s frozen down, you copy that”

“You got it shut?”

“Shut tight.”

“Here,” Stevens said hoarsely, tapped her arm. ‘Vacate. I’ll get the section up to normal. Sorry about that.”

“Sure,” she said. She slid clear of the cushion and he slid in.

“Just go on,” he said. “I’ll take care of it, do a little housekeeping. Take a break, you and Curran. We don’t need to keep rigid schedules. God knows she’s run without it”

Curran might have gone on sitting, obstinate; she gathered him up with a quiet, meaningful glance, a slide of the eyes in the direction Neill and Deirdre had gone. “All right,” he said, and came with her, walked out of the bridge and down the corridor.

And stopped when she did, taking his arm, around the curve by the galley.

*He might hear, Curran signed to her. Pointed to the com system.

She knew that. She cast a look about, looking for pickups, found none closer than ten feet. “Listen,” she said, “I want you to keep it quiet with him. Friendly. I don’t know what the score is here.”

“What’s he running around there, with a sector frozen down? Contraband, you reckon?”

“I don’t know.—Curran, have you tried the doors on the cabins —the other cabins? Something terrible happened on this ship. I don’t know when and I don’t know what. Hit by the Mazianni, he says; but this—The loft is frozen; the cabins left—you know how they were left… there’s a slept-in bed around there, frozen down.”

“I tell you this,” Curran said in the faintest of whispers, “I don’t sleep well—in that cabin. Maybe he’s worried for himself– about us doing to him what occurs to him to do to us. I don’t like it, Allie. Most of all I don’t like that comp being locked up. That’s dangerous. And you know why he got us out of there… not to look over his shoulder while he works, that’s what. I wouldn’t put it past him, spying on us. Or murder, if it came to it”

“No,” she said, a shake of her head. “I don’t think that I never have.”

“You ever been wrong, Allie?”

“Not in this.”

He frowned, a look up from under his brows. “Maybe the record’s still good. And maybe we go on like this and we have a run-in with the military—what’s he going to do, Allie? Which way is he going to jump? I don’t like it.”

“He’s strung out I know it. I know it’s not right.”

“Allie—” He reached out, touched her shoulder, cousin for the moment and not number two. “Man and woman—he thinks one way with you and maybe he thinks he can get around you; but you let me talk it out with him and I’ll straighten it out. And I’ll get those comp keys. No question of it.”

“I don’t want that”

“You don’t want it, I don’t want it. But we’re in trouble, if you haven’t noticed. That man’s off the brink and he’s going farther. I propose we have it out with him… we. Me. No chaff with me. He knows that. You just stay low, stay out of it, go to your cabin and we’ll put the fear in him.”

“No.”

“You think of something that makes as good sense? You going to ask him and he’ll come over? I’ll figure you tried that.”

She bit at her lip, looked up the corridor, where Neill and Deirdre came down the horizon. “Sorry,” Neill said again; and Deirdre: “Who’s minding the ship?”

“He is.—What was it, around there?”

“Loft,” Deirdre said. She clenched her arms about her. “A mess —things ripped loose—panels askew—didn’t see all of it, just from the section door. Dark in there.—Allie…”

“I know,” she said. “I figured what was in there,” She thrust her hands into her pockets, started back.

“Where are you going?” Curran asked.

“To my cabin.” She looked back, straight at Curran, straight in the eyes. “I’m off. It’s your shift. Maybe you’d better get back to the bridge. I’ll be there—a while.”

Chapter XIII

Lucy had gotten along, running stable under auto: Sandor shut down comp and stared a moment at scan, numb, the dread of the warship diminished now. It was not going to jump with them: had no capacity to do that. Mallory herself was sitting still, watching– he could not imagine that much patience among the things they told of Mallory. He did not believe it: she was waiting for something, but it had nothing to do with him. He began to hope that she just wanted them out of her way.

And if it was other Mazianni she was hunting—if she expected other traffic. He got up, looked once and bleakly at the couch he had quit. There was a little time left in mainnight. But the effort to sleep was a struggle hardly worth it, lying there awake for most of the time, to sleep a few minutes and wake again. He had done that all the night. Nervousness. And no chance of banking out. Not as things were.

He headed for the shower, trusting the autopilot—a scandal to the Dubliners: he imagined that. They wore themselves out sitting watch and he walked off and left it. There were things that wanted doing—scrubbing and swabbing all over the ship, work less interesting to them, he was sure: but he began to think in the long term, a fleeting mode of thought that flickered through his reasonings and went out again. There was the loft—

They had never done anything about the loft, he and Ross and Mitri: no need of the space—Lucy was full of empty space; and walking there—they just avoided it. Put it on extreme powersave.

The cold kept curious crew out. When he was alone on the ship he had never gone past the galley. It was dead up there… until the Reillys started opening doors and violating seals. Opening up areas of himself in the process, like a surgery. He gathered his courage about it, the hour being morning: a man was in trouble who went to bed with panic and got up with it untransformed. He tried to look at it from other sides, think around the situation if not through it.

A little time, that was what he needed, to break the Reillys in and get himself used to them.

But the comp—

(Ross… they wouldn’t have given out that money for no reason. No one’s that rich, that they can spill half a million because a few of their people take a fancy to sign off—half a million for a parting-present…)

(People don’t throw money away like that. People aren’t like that.)

(Ross… I know what they want. I loved her, Ross, and I didn’t see; I was afraid—Pell would have taken the ship—and what could I do? But they think I’ve sold her; and maybe I have. What do I do, Ross?)

The warm water of the shower hit his body, relaxed the muscles: he turned up the cold on purpose, shocked himself awake. But when he had gotten out he had a case of the shivers, uncommonly violent… too little food, he reasoned; schedule upset. He reckoned on getting some of the concentrates: that was a way of eating without tasting it, getting some carbohydrates into his body and getting the shakes out.

They had to make jump tomorrow maindawn. He had to get himself strung back together. Mallory was not going to take excuses out there. Mallory wanted schedules and schedules she got

He dressed, shaved, dried his hair and went out into the corridor, back to the bridge.

Curran was sitting against a counter—Neill and Deirdre with him. “I’m for breakfast,” Sandor said. “I think we could leave her all right, just—”

“Want to talk to you,” Curran said. “Captain.”

He drew a deep breath, standing next to the scan console-leaned against it, too tired for this, but he nodded. “What?”

“We want to ask you for the keys. There’s a question of safety.

“We’ve all talked about it. We really have quite a bit of concern about it.”

“I’ve discussed that problem. With Allison. I think we agree on it”

“No. You don’t agree. And we’re asking you.”

“I’ll take up the matter with her.”

“Are you sure there’s no chance of our reasoning with you?”

“I told you.”

“I think you’d better think again.”

“There are laws, Mr. Reilly. And they’re on my side in this.” He started away from the counter, to break it off. The others moved, cutting off his retreat—his eye picked Deirdre, the one he could go over—but there was no running. He turned about and looked at Curran. “You want to settle this the hard way? Let’s clear the fragile area and talk about it.”

“Why don’t we?” Curran got off his counteredge and waved them all back, a retreat into the lounge area among the couches, but Sandor went for the corridor, toward the cabins, a slow retreat that drew all of them in that direction.

Allison was in her cabin. He was sure of that, the way he measured his own frame and Curran’s and knew who was going to win this one, especially if Curran got help. He reached for the door switch, and Curran caught him up and knocked his hand aside.

He landed one, a knee to the groin and a solid smash to the neck that knocked Curran double—a knee to the face, and Curran hit the wall as he spun about to see to Neill.

A blow at his legs staggered him and Neill and Deirdre moved all at once as Curran tackled him from behind and weighed him down.

He twisted, struck where he had a moment’s leverage, over and over again—almost flung himself up, but a wrench at his hair jerked him hard onto his back and they had him pinned. “Out of it,” Neill ordered someone. “Out.” He kept up the struggle, blind and wild, hunting any leverage, anything. “Look out.”

A blow smashed across his jaw, for a moment absorbing all his wit, a deep black moment without organization: he knew they had his arms pinned, and his coordination was gone.

“Look at me,” a male voice was saying. A shake at his hair, a hand slapping his face and steadying it “You want to use sense, Stevens? What about the keys?”

There was blood in his mouth. He figured they would hit him again. He heaved to get a hand loose.

A second blow.

“Stop it,” Neill’s voice. “Curran, stop it.”

Again the hand shook at his face. He was blind for the moment, everything lost in dark. “You want to think it over, Stevens?”

He tried to move. The blood was shut off from his right hand; the left had life in it. He heaved on that side, but the lighter weight on that arm was still enough. “Curran.” That was Deirdre. “Curran, he’s out—stop it.”

A silence. His eyes began to clear. He stared into Curran’s bloody face, Neill and Deirdre’s bodies in the corner of his eyes, holding onto his arms. “You shouldn’t have hit him like that,” Neill said. “Curran, stop, you hear me, or I’ll let him loose.”

Curran let go of his face. Stared down at him.

“He’s not going to give us anything,” Deirdre said. “We’ve got trouble, Curran. Neill’s right”

“He’ll give it to us.”

“Curran, no.”

“What do you want, let him up, let him back at controls where he can do what we can’t undo? No. No way. You’re right, we’ve got trouble.”

Sandor gave a heave, sensing a loosening of Deirdre’s arms. It failed; the hold enveloped his arm, yielding, but holding. “Get Allison,” he said, having difficulty talking. And then he recalled it was her door they were outside. She might have heard it; and stayed out of it. The realization muddled through him in the same tangled way as other impressions, painful and distant. “What do we do?” Neill asked. “For God’s sake what do we do?”

“I think maybe we’d better get Allison,” Deirdre said.

“No,” Curran said. “No.” He took hold again of Sander’s bruised jaw. “You hear me. You hear me. You’re thinking how to get rid of us, maybe; not the law—that’s not your way, is it? Thinking of having an accident—like maybe others have had on this ship. We’ll find you a comfortable spot; and we’ve got all the time we like. But we’re coming to an agreement one way or the other. We’re having a look at the records. At comp. At every nook and cranny of this ship. And maybe if we don’t like what we find, we just call Mallory out there and turn you over to the military. You can yell foul all you like: you think that’ll make a difference if we swear to the contrary? Your word against ours—and what’s yours worth without ours to back it? They’d chew you up and swallow you down—you think not?

He started shivering, not from fear, from shock: he was numb, otherwise, except for a small quick area of shame. They picked him up off the floor and had to hold him up for the moment; he got his feet under him, did nothing when Curran grabbed his arm and pushed him into the wall. Then he hit, once and proper.

Curran hit the wall and came back off it. “No,” Neill yelled, and got in the way of it. And suddenly Allison was there, the door open, and everything stopped where it was.

No shock. Nothing of the kind. Sandor stared at her, a reproach.

“Sorry,” Curran said in a low voice. “Things seem to have gotten out of hand.”

“I see that,” she said.

“I don’t think he’s willing to talk about it”

“Are you?” she asked.

“No,” Sandor said. His throat hurt. He said nothing else, watched Allison shake her head and glance elsewhere, at nothing in particular.

“How do we settle this?”

She was talking to him. “Forget it,” he said past the obstruction in his throat. “It was an idea that won’t work. We go on and forget it. I’ve got no percentage in carrying a grudge.”

“I don’t think it works that way,” Curran said.

“No,” she said, “I don’t either.”

“There’s cabins,” Curran said.

“Lord-”

“It’s done. I figure a little time to think about it—Allie, we don’t sleep with him loose.”

“You can’t lock them,” she said. “Without the keys.”

“I’d laugh,” Sandor said, “but what comes next? Cutting my throat? Think that one through: you kill me and you’ve got no keys at all. We’ll go right on out of system.”

“No one’s talking about that.”

“I’ll lay bets you’ve thought about it.—No, I’ll go upsection. Close a seal. An alarm will ring if I leave it. You have to have everything laid out for you? You’re inept, you Dubliners. Ought to take you several days to work yourselves up to the next step.”

He walked off from them, toward the section two cabins, reckoning all the while that they would stop him and devise something less comfortable. There was silence behind him.

He passed the section seal, pressed the button.

The seal shot home.

Allison sat down on the armrest of the number two cushion and looked at her cousins—at Curran, who sat on the arm of number one, blotting at a cut lip. Neill and Deirdre rested against the central console slumped down and very quiet. “How?” she asked.

Curran shrugged—looked her in the eyes. “It just got out of hand.”

“When?”

Curran ducked his head. He was bloodstained, sweating, his right eye moused at the cheekbone. “He swung,” he said, looking up again. “Caught me. He won’t bluff.” It was possibly the worst moment of Curran’s life, being wrong in something he had argued. Her own gut was tied in a knot.

And after that, silence, all of the faces turned toward her, where the decisions should have come from in the first place. She leaned her arms on her knees, adding it up, all the wrong moves, and the first was abdicating. It made her sick thinking of it All the good reasons, all the rationale collapsed. It was not only an ugly way to have gone, for good reasons—the game had not worked, and now it was real: Stevens understood it for real—or knew that they knew it had to be. “It’s stupid,” she objected, slammed her fist into her hand. She looked up at faces that had no better answer. “No ideas?”

Silence.

“We could get him off this ship,” Curran said in a subdued voice. “We could ask the military to intervene. Say there was an argument.”

“You reckon to do that?”

“We’re talking about our lives. Allie, don’t mistake him like I did: he backed up on the docks, but he’s been running hired crew and he’s survived; there’s those cabins. And the loft.”

“It was depressurized,” Deirdre said. “Maybe he got holed in some tangle; but little ships don’t survive that kind of thing. The other answer is some access panel going out; and you can blow it from main board, can’t you?”

“So what do we do? We’ve got twenty-four hours to get those comp keys out of him or to get him back at controls, or we go sliding right past our jump point and out of the system. And he knows it.”

Silence.

“Allie,” Curran said, “he’s a marginer. At best he’s a liar and a thief. He’s lied his way from one end of civilization to the other. He’s conned customs and police who know better. At the worst– at the worst—”

“You think he’s conned me?”

“I think he was desperate and we gave him a line. But he’s keeping the keys in his hands and maybe he’s had other crew aboard who never made it off. We don’t know that. We can’t let him loose.”

“You got another idea? Calling the military—that still doesn’t give us the keys. They’d have to haul us down; or we lose the ship. Might as well apply to leave the ship ourselves. Hand it back to him. Go back to Pell, beached. In a year, maybe we can explain it all to the Old Man. And go back to Dublin and go on explaining it. You think of that?”

“What do we do, then?”

“He’s got no food in that section,” Deirdre said. ‘There’s that. There’re things he needs.”

Allison drew a long breath, short of air. So they were around to that, the logical direction of things. “So maybe we come up with something more to the point than that. That’s what he was saying, you know that? He knows what kind of a mess we’re in. We can’t rely on him at controls—how much do you think you can rely on comp keys he might give us if we put the pressure on? He’s out-thought us. He’s not going to bluff.”

Silence.

She rested her hands on her knees and stood up. “All right. It’s in my watch. So I’ll talk to him. I’m going up there.”

“Allie-”

“Al-li-son.” She frowned at Curran. “You stay by com and monitor the situation. Only one way he’s going to trust us halfway —a way to patch up things, at least; make a gesture, make him think we think we’ve straightened it out. God help us.” She headed for the corridor, looked back at a trio of solemn faces. “If you have to come after me, come quick.”

“If he lays a hand on you,” Curran said, “I’ll break it a finger at a time.”

“Don’t take chances. If it gets to that, settle it, and call the military.” She walked on, raw terror gathered in her stomach. Her knees had a distressing tendency to shake.

There was no more chance of trusting him. Only a chance to make him think they did. He was, she reckoned, too smart to kill her even if it crossed his mind: he would take any chance they gave him, come back to them, bide his time.

She hoped to get them to Venture Station alive: that was what it came to now. And if they were lucky, there might be a strong military authority there.

He sat in the corridor—no other place in section two that was heated: he had the heat started up in number 15, and if the sensors worked, the valve that shut the water down in 15 would open and restore the plumbing. He never depended on Lucy’s plumbing. At the moment he was beyond caring; he was pragmatic enough to reckon priorities would change when thirst set in.

And in an attempt at pragmatism he made himself as comfortable as he could on the floor, nursed bruised ribs and wrenched joints and a stiff neck, trying to find a position on the hard tiles that hurt as little as possible. The teeth ached; the inside of his mouth was cut and swollen: there was a great deal to take his mind off more general troubles, but generally he was numb, the way the area of a heavy blow went numb. And he reckoned that would start hurting too, when the shock of betrayal had passed. In the meantime he could sleep: if he could find a spot that did not ache, he could sleep.

The alarm went off—the door down the curve opened from their side, jolting his heart. He scrambled up—staggered into the wall and straightened.

Allison by herself. The door closed again; the alarm stopped. He stared at her and the numb spot gained feeling and focus, an ache that settled everywhere. “So, well,” he said, “got around to figuring how it is?”

“Look, I’m here. You want to talk or do you want me to let be?”

“I won’t give it to you.”

She walked closer, the length of the corridor between them. Stopped near arm’s length. “I won’t pass it to Curran. I’m sorry.– Listen to me. I reckoned maybe we were too close for reason. I just figured maybe Curran could get the sleepover out of it; maybe– Hang it, Stevens, you’re strung out on no sleep and you’re risking our lives on it. Not just mine. Theirs; and I got them into it You don’t trust them. Maybe not me. But I figured if you and Curran could sort it out—maybe it would all work. That maybe if you got it straight with them, if all the heat blew out of it—”

“Misfigured, did you?”

“Don’t be light with me. Say what you think.”

“All I want—” His throat spasmed. He thrust his hands into his pockets and disguised a second breath with that. “I don’t give you the time of day, Reilly. Let alone the comp keys. Now we can go on like this. And maybe you’ll think of other clever ways to get at it. But you loaned me money; you didn’t buy me out You figure —what? To trump up something to get me between you and the police at Venture? And then to offer me another deal? Sorry. I’ve got that figured out. Because if they get me, Reilly, you’re stuck on a ship you can’t even get out of dock. Embarrassing. Might raise questions about your title to her. Might cost you a long time to get that straightened out, long-distance to Pell and wherever Dublin might be. Not to mention—if they send me in for restruct —I’ll spill what happened here, all in the little pieces of my mind. And there goes the Reilly Name. So refigure, Reilly. Nothing you do that way’s going to work.”

“You’re crazy, you know that?”

“You know, I really took precautions. I signed on drunks and docksiders and insystemers, and I got through with all of them. I figured a big ship like Dublin might try to doubledeal me, but you’re pirates, Reilly—I never figured that. Mallory’s out there hunting Mazianni and here’s a ship full of them.”

Her face flushed. He had that satisfaction. “You don’t take that seriously, do you?”

“I don’t see a difference.”

“Stevens-”

“Sandor. The name’s Sandor.”

“I’m sorry for what happened. I told you why; I told you– Look, Curran thought you’d bluff. That was his thinking. Now he knows better. So do all of us. You want to come back to the bridge and sort this out?”

He ran that through his mind several ways, and none of it eased the ache. Stood there, obstinate, only to make it harder.

“Stevens—what’s it take?”

“Worried, are you? We’re not even near the Jump point. And what when we’re across it? A replay? I only go for this once,

Reilly. The next time you lay a hand on me if it’s war. You’ll get me. Sure you will. I’ve got to sleep, after all. But let’s just lay it on the table. You may not be able to haul it out of me. And then what? Then what, Reilly?”

“It’s crazy to talk like that.”

“How much do you want this ship?”

“A lot. But not that way. I want us working with each other. I want our hands clean and all of us in one piece, not killed because you’re still running a loaded ship like a margin cargo—you’re blind crazy, Stevens. Sandor. You’ve got too many enemies in your own head.”

“It doesn’t work. You take it on my terms. That’s all you’ve got. Up the ante, and that’s still all you’ve got.”

“All right,” she said after a moment, stood there with a look in her eyes that seemed halfway earnest She nodded toward the section seal. “Let’s go.”

He nodded, walked along with her. “They’re listening,” he said in a low voice. “Aren’t they?”

She looked at him, a sudden, disturbed glance. They reached the section seal and she stopped and reached for the button. He was quicker, his hand covering it. He looked her in the eyes, that close, and the closeness murdered reason for the instant. The scent of her and the warmth and the remembrance of Viking and Pell.

“You could have had it all,” he said. “You know that.”

“You never trusted us. Not from the start”

“I was right, wasn’t I?”

She was silent a moment. “Maybe not.”

The quiet denial shot around the flank of his defenses. He turned his head, pressed the button.

The siren went. The door shot open. He was facing Curran and Neill. He was somehow not surprised.

“He’s coming back,” Allison said. She closed the door again. The siren stopped. “We’ve got it settled.”

The faces in front of him did not believe it. He reacquired his own doubts, nerved himself with the insolence of a thousand encounters with docksiders. Offered his hand.

Curran took it, a small shudder of hesitation in the move, a grip that spared bruised knuckles—but Curran’s hand was in no better condition; Neill’s next—Neill’s earnest expression had a peculiar distress.

“Sorry,” Neill said.

He meant it, Sandor reckoned. One of them meant it And knew it was all a sham. He felt a pang of sympathy for Neill, which was insane: Neill would be with the rest of them, and he never doubted it.

“Deirdre’s on watch, is she?”

“Yes.”

“I’m going to have my breakfast and wash up. And I’ll rest after that… find myself a cabin and rest a few hours. You’ll wake me if something comes up.”

He walked on—away from them. Stopped in the galley and opened the freezer, pulled out a decent breakfast, pointedly keeping his back to the rest of them as they passed.

It was a quiet supper, hers with Curran. Curran was eating carefully, around a sore mouth, and not in a mood for idle conversation. Neither was she. “You think he’ll go along with it all the way to Venture?” Curran asked once. “Maybe,” she said. “I think he’s had the angles figured for years. We just walked into it.”

And a time later: “You know,” Curran said, “the whole agreement’s a lie. Look at me, Allie. Don’t take on a face like that He’s a liar, an actor—he knows right where to take hold and twist I knew that from the start If you hadn’t stepped in when you did—”

“What would you have done? I’d like to have known what you would have done.”

“I’d have beaten a straight answer out of him. He says not But that’s part of the act. He’s harder than I thought, but I’d have peeled the nonsense away and gotten right where he lives, Allie, don’t think not Wouldn’t have killed him; not near. And it might have settled this. You had to come out the door—”

“It didn’t go your way the first time. How much would it take? How many hours?” Her stomach turned. She pushed the food around on her plate, made herself spear a bite and swallow. “You heard what he said. We’ve got him working now. Another set-to—”

“You go on believing what he says—”

“What if it is the truth? What if it’s the truth all along?”

“And what if it’s not? What then, Allie?”

“Don’t call me that. I don’t like it.”

“Don’t redirect You know what the stakes are. We’re talking about trouble here. You sit the number one; you’ve got to have the say in it But you’re thinking below the belt.”

That’s your assumption.”

“Don’t tell me a male number one wouldn’t have gotten us in this tangle.”

“Ah. There we are. What if it were a woman and it were you calling the shots? Dare I guess? You’d take it all, wouldn’t you? You think you would. But would you sleep sound in that company? No. You think it through. I’m not sleeping with him. And he even asked.”

“Maybe you should have.”

She was reaching for the cup. She slammed it down, spilling it. “You need your attitudes reworked, Mr. Reilly. You really do. Maybe we really need to figure the logic that carries all that. Let’s discuss your sleepovers, Mr. Reilly—or don’t they have any bearing on your fitness to command?”

His face went red. For a moment he said nothing at all. Then his eyes hooded and he leaned back. “Hoosh, what a tongue on ye, Allie. Do you really want the details? I’ll give you all you like.”

She smiled, a move of the lips, not the rest of her face. “Doubtless you would. No doubt at all. You had your try; and he knocked you flat, didn’t he? So while we’re discussing my personal involvement here, suppose we add that to the count: is it just possible you have something personal at stake?”

“All of that’s aside. The question’s not what we see; it’s what Stevens is… and where we are. And what we do about it.”

“And I’m telling you it didn’t work.”

“You stopped it. It’s ugly; it’s an ugly thing; I don’t like it; but it would have settled it and your way hasn’t got us anywhere but back behind start. Way behind.”

She thought that over, and it was true, “Where did we ever get off doing something like this? Where did we ever learn to think about things like this?”

“It’s not us. It’s the company you came up with.”

“Suppose he told the truth. Suppose that for a minute.”

“I don’t suppose it. You’re back where you were, falling for a good act. And you think every customs agent and banker who ever believed him didn’t think he looked sincere? Sincere’s his stock in trade, him with that fair, blue-eyed innocence.”

She took a napkin, blotted the spilled coffee, wiped the bottom of the cup and took a drink, and a second.

“So we go on,” Curran said. “Next jump—and him running it.”