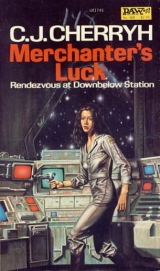

Текст книги "Merchanter's Luck "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Lucy’s cold eye located the appropriate reference star, bracketed it, and he saw that The terror he ought to feel eased into a bland, tranked consciousness in which death itself might be a sensation mildly entertaining. He started the jump sequence, pushed the button which activated the generation vanes while the buoy squalled protest about his track—felt it start, the sudden, irreversible surety that bizarre things were happening to matter and to him, that things were racing faster and faster…

… conscious again and still tranked, hyper and sedated at once, a peculiar coincidence of mental states, in which he was aware of alarms ringing and Lucy doing her mechanical best to tell him she was carrying dangerous residual velocity. The power it took to dump had to be measured against the power it took to acquire—No dice throws. Calculate. Move the arm, punch the buttons. Dump the speed down to margin or lose the ship on the next-Wesson’s Point: present location, Wesson’s Point, in the appropriate jump range. Entry, proceeding toward dark mass: plot bypass curve down to margin; remember the acquire/dump balance—

“Sandy” That was Ross’s comp’s voice. “Sandy, wake up. Get the comp.”

There were other voices, that sang to him through the hum of dissolution.

Dead, Sandor. All dead. Sandy, -wake up. Time to wake up. Vent!

… acceptable stress. Set to auto and trank out for time of passage; set cushion and pulser; two hours two minutes crossing the nullpoint, set, mark. Dead, Sandor. All dead.

He came out of sleep with the pulser stinging his wrist and with an ache all the way to his heels, unbelted and leaned over the left side of the cushion to dryheave for a moment, collapsed over that armrest weighing far more than he thought he should and caring far less about survival than he should, because he had gone into this too tired, with his defenses too depressed, and the trank was not wearing off. He ought to be attending to controls. He had to get something to eat and drink, because he was going again in half an hour, and that was too little time.

He reached down and got one of the foil packets, managed with palsied fingers to get it open, and got the ripped corner to his lips —chewed food which had no taste but salt and copper—felt after the water and sucked mouthfuls of that, dropped the empty foil and the empty bottle, felt the food lying inert in his stomach, unwanted. He got the other shot home, beginning to trank out again… forced his eyes to focus on the boards, while Lucy shot her way along at a hairbreadth margin from disaster. Sometimes there was other junk ringing a nullpoint, a dark platelet of rocks and ice and maybe, maybe lost spacers who used the deep dark of this place for a tomb…

He held his eyes open, alternately trying to throw up and trying to cope with the flow of data which comp itself had to sort and dump in a special mode because it came so fast… still blind, ripping along at a velocity that would fling even a smallish planet into his path before the computer could deal with it Lucy headed for the other side of the nullpoint’s gravity well with manic haste, but in that close pass they had gotten bent as light was bent, and the calculations had to take that into account. He sat there ignoring the scan-blindness into which they were rushing, trying to tell by the fluttering passage of data whether the numbers converged, reality with his calculations, trying to learn if there was error in position, and how that was going to translate in jump.

And screaming in the back of his mind was the fact that he was playing tag with a very large ship which could play games with distances which Lucy barely made, in a time differential he could not calculate, and that on some quirk of malign fate he could still run into them, if they just happened to coincide out here. Dublin was either here now or out ahead of him, because his lead was going to erode and change to lag somewhere in the transit. Ships missed each other because space was wide and coincidences were statistically more than rare; but not when two ships were playing leapfrog in the same nullpoints…

Second jump… statistically better this time… a vast point, three large masses in juxtaposition, a kink in the between that hauled ships in and slung them along in a complicated warping… Dump it now, dump the speed down…

‘Wake up, Sandy.”

And his own voice, prerecorded: “The referent now is Pell’s Star. Push the track reset, Sandy. The track reset…”

He located the appropriate button, stared entranced at the screen… no rest possible here. The velocity was still extreme. His tongue was swollen in his mouth. He took another of the water bottles and drank, hurting. Food occurred to him; the thought revolted him; he reached nonetheless and located the packet, ate, because it was necessary to do.

He was crazy, that was what—he swallowed in mechanical, untasting gulps, unable to remember what buttons he had pushed, trusting his own recorded voice giving him the sequences as comp needed them, trusting to that star he saw bracketed ahead of him, if that was not itself a trick of a mind which had come loose in time. He recalled Dublin; if Allison Reilly knew remotely what he was doing this moment she would curse him for the risk to her ship. He ought to dump more of the velocity he had, right now, because he was scared. Tripoint was deadly dangerous, with no margin for high-speed errors…

But Lucy was moving with the sureness of a woman with her mind made up, and he was caught in that horrible impetus and the solid power of her, because a long time ago she had hollowed him out and taken all there was of him. He moved in a continual blur of slow motion, while the universe passed at much faster rates. There was debris in this place. He was passing to zenith of the complicated accretion disc… so he hoped. If he had miscalculated, he died, in an impact that would make a minor, unnoticed light.

He dumped down: the recorded voice told him to. He obeyed. The data coming in sorted itself into more manic strings of numbers. He punched in when the voice told him, froze a segment, matched up—found a correspondence with his plotted course. He grinned to himself, still scared witless, human component in a near C projectile, and stared at the screens with trank-dulled eyes.

He kicked into Pell jump range with velocity that had the incoming-range buoy screaming its automated indignation at him, advising whatever lunatic had just come within its scan that he was traveling too fast and headed dead-on for trafficked zones.

Dump! it warned him, dopplered and restructured by his com. Its systems were hurling machine-to-machine warnings at Lucy’s autoalert, which Lucy was primed to obey. She was kicking in the vanes in hard spurts, which shifted him in and out of realspace in bursts of flaring nausea. There were red lights everywhere until he hit the appropriate button and confirmed the dump order Lucy was obeying.

Chapter IV

The velocity fell away: some time yet before the scan image had time to be relayed by the buoy to Pell central, advising them that a ship was incoming, and double that time before central’s message could come back to Lucy. Sandor extricated himself from his nest with small, numb movements, offended by the reek of his own body. His mouth tasted of copper and bile. His hands were stiff and refused coordinated movement. He rolled out of the cushion in the pit and hit the deck on his knees in a skittering of empty water bottles and foil papers sliding under his hand. “Wake up, Sandy,” comp was telling him. He reached the keyboard still kneeling, hooked an arm over it and managed to code in the one zero one that stopped it, about the most that his numbed brain was capable of doing in straight sequence.

Wake up. Not that much time left before they would want answers out of him, before his absence from controls would be noticed. He had the pulser still on his wrist. He levered himself up by his arms on the counter, looked at the blurring lights and the keys, trying to recall the sequence that would put it on watch. Autopilot was still engaged: Lucy was following lane instructions from the buoy. That was all right.

He located the other control, while his stomach spasmed and his vision grayed, got the code in—no acceleration now. He could not have stood with any stress hauling at him. He groped for the edge of the counter at his right and worked his way up out of the pit, walked blind along the counter until he blinked clear on the lighted white of the corridor that led to maintenance storage, and the cubbyhole of a shower in the maintenance section. He peeled everything off that he was wearing, shoved it in the chute and hoped never to see it again, felt his way into the cabinet and leaned there while the jets blasted off filth and dead skin and shed hair. Soap. He lathered; found his razor in its accustomed place and shaved by feel, with his eyes shut and the water coursing over him. He felt alive again, at least marginally. He never wanted to leave the warmth and the cleanliness… could have collapsed to the floor of the cabinet and curled up and slept in the warm water.

No. Out again. There was not that much time. He shut the water off, staggered out into the chill air and gathered clothes from the locker there. He half-dried, pulled the coveralls on and wiped his wet hair back from his eyes. The pulser, waterproof, had not alerted him: Lucy was still all right. He went out into the corridor with an armload of towels and disinfectant and went back to clean up the pit, smothering the queasiness in his stomach.

He disposed of all the untidiness, another trip back to storage and disposal, then came back and fell into the cushion that stank now of disinfectant… shut his eyes, wilted into the contours, fighting sleep with a careful periodic fluttering of his eyelids.

They already had his ID, lying though that was. It was automatic in Lucy’s computer squeal, never ceasing. He had the station scan image from the buoy, estimates of the positions of all the ships in Pell System, large and small—and when he brought his mind to focus on that, on the uncommon number of them, a disturbance wended its way through his consciousness, a tiny ticking alarm at the scope of what he was seeing. Ships in numbers more than expectation. Traffic patterns, lanes in great complexity, shuttle routes for approach to the world of Downbelow, to moons and mining interests. A collection of merchanters, who got together to set rates and to threaten Union with strikes; who served Union ports and disdained the combines… That was all it had been. But it had grown, expanded beyond his recollections. Sol trade—sounded half fanciful, until now.

Harder to run a scam here, if they were short and overcrowded. Or it might even be easier, if station offices were too busy to run checks, if they were getting such an influx on the strength of these rumors that a ship with questionable papers could lose itself in the dataflow… no, it was just a matter of rethinking the approach and the tactics…

“This is Pell central,” a sudden voice reached him, and the pulser stung him mercilessly, confusing him for the instant which to reach for first. He shut the pulser down, keyed in the mike, leaning forward. “You have come in at velocity above limit. Consult regulations regarding Pell operational restrictions, section 2, number 22. This is live transmission. Further instruction assumes you have brought your speed within tolerance and keep to lane. If otherwise, patrol will be moving on intercept and your time is limited to make appropriate response. Query why this approach? Identify immediately… We are now picking up your initial dump, Lucy. Please confirm ID and make all appropriate response.”

It was all ancient chatter, from the moment of station’s reception of his entry, the running monologue of lightbound com that assumed he could have begun talkback much, much earlier.

“We don’t pick up voice, Lucy. Query why silence.”

He reached lethargically for the com and punched in, frightened in this pricklishness on station’s part. “This is Stevens’ Lucy inbound on 4579 your zenith on buoy assigned lane. I confirm your contact, Pell central. Had a little com trouble.” This was a transparent lie, standard for any ship illicitly out of contact. “Please acknowledge reception.” In his ear, Pell was still talking, constant flow now, telling him what it perceived so that he would know where he was on the timeline. “Appreciate your distress, Pell central. This is Stevens talking, of Stevens’ Lucy, merchanter of Wyatt’s Star Combine, US 48-335 Y. Had a scare on entry, minor malfunction, put me out of contact a moment. I’m all right now. Had a backup engaged, no further difficulty. Please give approach and docking instructions. I’m solo on this run and wanting a sleepover, Pell central. I appreciate your assistance. Over.”

Communication from Pell ran on, an overlapping jabber now, as the com board gave up trying to compress it and created two flows that would drive a sane man mad. He slumped in the seat which embraced him and held his aching bones, unforgiving even in its softest places. He blinked from time to time, kept his eyes open, to make sure the lines on the approach graph matched. He listened for key words out of the com flow, but Pell seemed convinced now that he was honest—still possible, another, dimmer voice insisted in his head, that some patrol ship could pop up out of nowhere, meaning business.

Station op, in the long hours, began to send him questions and instructions. He was on the verge of hallucinating. Once station queried him sharply, and he woke in a sweat, eyes scanning the instruments wildly, trying to find out where he was, how close—and too close, entering the zone of traffic.

“You all right, Lucy?” the voice was asking him. “Lucy, what’s going on out there?”

“All right,” he murmured. “I’m here. Receiving you clear. Say again, Pell central?”

Getting in was nightmare. It was like trying to line up a jump blind drunk. He stared slackjawed at the screens and did the hairbreadth lineup maneuvers on visual alone, which no larger ship could have dared try, but he was far too fuzzed to use comp and read it out, only to take its automated warnings, which never came. He was proud of himself with a manic satisfaction as he made the final touch, like the same drunk successfully walking a straight line: only one beep out of comp in the whole process, and Lucy nestled into the lockto dead center.

He was so satisfied he just sat there. Dockside com came on and told him to open his docking ports, and his hands were shaking so violently he had trouble getting the caps off the switches.

“This is Pell customs and dock security,” another voice came through. “Have your papers ready for inspection.”

He reached for com. “Pell customs, this is Stevens of Lucy. We’ve come in without cargo due to a scheduling foulup at Viking. You’re welcome to check my holds. I’m Wyatt’s Star Combine. I’m carrying just ship-consumption goods. Papers are ready.” He tried to gather his nerves to face official questions, suddenly recalled the gold stored in a drop panel in the aftmost hold, and his stomach turned over. He reached and opened the docking access in answer to a blinking light and a repeated request from dock crews on the shielded-line channel, and his ears popped from the slight pressure change as the hatch opened. “Sorry, Pell dock control. Didn’t mean to miss that adjustment. I’m a little tired.”

A pause. “Lucy, this is Pell Dock Authority. Are you all right aboard? Do you need medical assistance?”

“Negative, Pell Dock Authority.”

“Query why solo?”

He was too muddled to think. “Just limped in, Pell Dock.” The fear was back, a knot clenched in the vicinity of his stomach. “This is a hired-crew ship. My last crew met relatives on Viking and ran out on me. I had no choice but to take her out myself; and I couldn’t get cargo. I limped in all right, but I’m pretty tired.”

There was a long silence. It frightened him as all thoughtful reactions did, and sent a charge of adrenalin through him. “Congratulations, then, Lucy. Lucky you got here at all. Any special assistance needed?”

“No, ma’am. Just want a sleepover. Except—is Reilly’s Dublin at dock? Got a friend I want to find.”

“That’s affirmative on Dublin, Lucy. Been in dock two days. Any message?”

“No, I’ll find her.”

A silence. “Right, Lucy. We’ll want to talk to you about dock charges, but we can do the paperwork tomorrow if you’re willing to leave your ship under Pell Security seal.”

“Yes, ma’am. But I need to come by your exchange and arrange credit”

A pause. “That was WSC, Lucy?”

“Wyatt’s Star, yes, ma’am. A twenty, that’s all. Just a drink, a sandwich, and a place to sleep. Want to open an account for WSC at Pell. Transfer of three thousand Union scrip. I can cover it.”

Another pause. “No difficulty, Lucy. You just leave her open all the way and we’ll put our own security on it while customs checks her. What’s your Alliance ID?”

Apprehension flooded through him, rapid sort in a tired brain. “Don’t have that, Pell Dock. I’m fresh from Unionside.”

“Unionside number, then.”

“686-543-5608.”

“686-543-5608. Got you clear, then, Lucy, on temporary. Personal name?”

“Stevens. Edward Stevens, owner and captain.”

“Luck to you, Stevens, and a pleasant stay.”

“Thank you, ma’am.” He reached a trembling hand for the board, broke contact and shut down everything, put a lock on comp and on the log; and already in the back of his mind he was calculating, about the gold, about turning that with a little dock-side trade, a little deal off the manifest, very quiet, putting the profit into account, making it look right. There were ways. Dealers who would fake a bill. It might be good here. Might be the place he had hoped to find. And Dublin…

She was here.

He hauled himself out of the cushion and walked back to the access lift at the side of the lounge, opened the hatch below and got a waft of mortally cold air. He got a jacket from the locker, shrugged it on and patted his coveralls pocket to be sure he had the papers, then committed himself and took the lift down into the accessway, got out facing the short dingy corridor to the lock, and the yellow lighted gullet of the station access tube at the end. He shivered convulsively, zipped his jacket, and walked down and through the tube into the noise of the dock and the thumping of the machinery that was busy blowing out Lucy’s small systems.

Customs was there. Police were. A noisy horde of stationers beyond the customs barrier, a crowd, a riot. He stopped in the middle of the access ramp with the customs agents walking toward him—neat men in brown suits with foreign insignia. His expression betrayed shock an instant before he realized it and tried to ignore it all as he fumbled his papers out of his pocket. “I talked with the dockmaster’s office,” he said, offering them. His heart beat double time as it did at such moments, while the crowd kept up the noise and commotion beyond the barricade. The senior officer looked over the forged papers and stamped them with a seal. “Your office is supposed to put my ship under seal,” Sandor went on, trying not to look at the police who waited beyond, trying not to harass the agents at their duty. “Got no cargo this trip. They fouled me up at Viking. I’m bone tired and needing sleep. No crew, no passengers, no arms, no drugs except ship’s use pharmaceuticals. I’m headed for the exchange office right now to get some cash.”

“Carrying money?”

“Three thousand Union scrip aboard. Not on me. They promised me I could do the exchange papers later. After sleep.”

“Items of value on your person?”

“None. Going to a sleepover. Going to get a station card.”

“We’ll locate you on the card when we want you.” The man looked up at him. It was the same face customs folk gave him everywhere, hardly welcoming. Sandor gave it back his best, earnest stare. The man handed the false papers back and Sandor stuffed them into his inside breast pocket, started down the ramp.

The police moved in. “Captain Stevens,” one said.

He stopped, his heart jumping against his ribs.

“You’ll want to pick up a regulations sheet at the office,” the officer said. “Our procedures are a little different here than Union-side.—Did they give you trouble clearing Viking, then?”

He stared, simply blank.

“Lt. Perez,” the officer identified himself. “Alliance Security operations. Was it an understandable scheduling error? Or otherwise?”

He shook his head, confused in the crowd noise that echoed in the distant overhead. The question made no sense from a dock-side policeman. From Customs. From whatever they were. “I don’t know,” he said. “I don’t know. I’m a marginer. It happens sometimes. Somebody didn’t have their papers straight. Or some bigger ship snatched it. I don’t know.”

The policeman nodded, once and slowly. It looked like dismissal. Sandor turned, hastened on through the barrier and toward the milling crowd, afraid, trying not to walk like a liberty-long drunk and trying to figure out why they chose his section of the dock to gather and what it all was.

‘Hey, Captain,” someone yelled as he met the crowd, “why did you do it?”

He looked that way, saw no one in particular, cast about again as he pushed his way through. Panic surged in him, wanting out, away from this place. Hands touched him; a camera bobbed over the shoulders of the crowd and he stared into the lens in one dim-witted moment of fright before ducking away from it

“What route?” someone asked him. “You find some new null-point, Captain?”

He shook his head. “Nothing like that. I just came through Wesson’s and Tripoint.” He kept walking, terrified at the stationers who had come to stare at him. Someone thrust a mike in his face.

“You know the whole station’s been following your com for five hours, Captain? Did you know that?”

“No.” He stared helplessly, realizing—his face… his face recorded, made public, with Lucy’s name and number. “I’m tired,” he said, but the microphone persisted, thrust toward him.

“You’re Captain Edward Stevens, right? From Wyatt’s Star? What’s the tie with Dublin? She, you said. Personal?”

“Right.” A small voice, a tremulous voice. His knees were shaking. “Excuse me.”

“How long have you been out?” The mike followed him, persistent “You have any special trouble running solo, Captain?”

“A month or so. I don’t know. I haven’t comped it yet. No. I don’t know.”

“You’re meeting someone of Reilly’s Dublin, you said.”

“I didn’t say. It’s personal.” He hesitated, searched desperately for a way of escape that would get him to the offices. Blue dock. That was where he had to go. Stations were universal in that arrangement, if not in their interiors. He was on green. It could not be far. He tried to recall the docks from years ago—he had been eleven—with Ross and Mitri by him—

“What’s her name, Captain? Is there more to it?”

“Excuse me, please. I’m tired. I just want to get to the bank. I didn’t do anything.”

“You cleared Viking to Pell in a month in a ship that size, solo? What kind of rig is she?”

“Excuse me. Please.”

“You don’t call what you did remarkable?”

“I call it stupid. Please.”

He shoved his way through, with people surging all about him, his heart hammering in panic. People—people as far as he could see. And of a sudden…

She was there. Allison Reilly was straight in front of him, wide-eyed as the rest of the crowd.

He shoved his way past the startled curious and at the last moment kept his hands off her—stood swaying on his feet and seeing the anger on her face.

“You’re crazy,” she said. “You’re outright crazy.”

“I told you I’d see you here. I’m tired. Can we talk… when I get back from the bank?”

She took his elbow and guided him through the crowd. The microphone caught up with him again; the newswoman shouted questions he half heard and Allison Reilly ignored them, pulled him across the dock to the line of bars—toward a mass of quieter folk, a line of spacers. Fewer and fewer of the stationer crowd pursued them; and then none: the spacer line closed about them with sullen and forbidding stares turned toward the intruding stationers. He paid no attention then where she aimed him—headed through the dark doorway of a bar and fell into a chair at the nearest available table. He slumped down over his folded arms on the surface in blessed quiet and tried to come out of it when someone shook him by the shoulder.

Allison Reilly put a drink into his hand. He sipped at it and gagged, because he had expected a stiff drink and got fruit juice and sugar froth. But it was food. It helped, and he looked up fuzzily into Allison’s face while he drank. A ring of other faces had gathered, male and female, spacers ringing the table, silver-clad, white, green and gold and motley insystemers, just staring—all manner of patches, all the same silent observation.

“Sandwich,” someone said, and he looked left as a male hand set a plate in front of him. He disposed of as much of it as he could in several graceless bites, then stuffed the rest, napkin-wrapped, into his jacket pocket, a survival habit and one which suddenly embarrassed him in the face of all these people who knew what the odds were and what kind of poverty would drive a man to push a ship like that. Dublin knew what he had done. Someone on Dublin had talked, and they knew he had done it straight through, stringing the jumps, the only way the likes of Lucy could possibly have tailed Dublin. They would arrest him soon; someone would talk it over with some official in station central, and they would start running checks and talking to merchanters all over this station, some one of whom might have a memory jogged: his now-notorious ship, his face, his voice carried all over station on open vid. He could not deal quietly, take that fourteen thousand gold off the ship, deal as he was accustomed to deal, quietly, on the docks. Not now. He was dead scared. Allison Reilly was there, and the look on her face was what he had wanted, but he was up against the real cost of it now, and he found it too much.

“Allison,” he said, when she sat down in the other chair and leaned on her arms looking at him, “I want to talk to you. Somewhere else.”

“Come on,” she said. “You come with me.”

He pushed the chair back and tried to get up… needed her arm when he tried to walk, to keep his balance in station’s too-heavy gravity. Some spacer muttered a ribald and ancient joke, about a man just off a solo run, and it was true, at least as far as the mind went, but the rest of him was dead.

He walked, a miserable blur of lights and moving bodies—the dock’s wide echoing chill and light and then a doorway, a confusion of bizarre wallpaper and a desk and a clerk—a sleepover, a carpeted hall in either direction from here… He leaned on the counter with his head propped on his hand while Allison straightened out the details and the finances. Then she took his arm again and led him down a corridor.

“Keep them out of here,” she yelled back at someone, who said all right and left; she carded a door open and put him through, into a sleepover room with a wide white bed.

He turned around then and tried to put his arms around her. She shoved him in the middle of his chest and he nearly fell down. “Idiot,” she said to him, which was not the welcome he had hoped for, but what he reckoned now he deserved. He stood there paralyzed in his misery and his mental state until she pulled him over to the bed and pushed him down onto it. She started working at his clothes with rough, abrupt movements as if she were still furious. “Roll over,” she hissed at him, and pulled at his shoulder and threw the covers over him.

And he fell asleep.