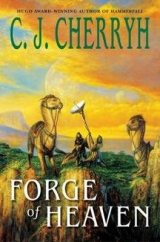

Текст книги "Forge of Heaven "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 30 страниц)

3

A DECENT TIP TO THE WAITRESS, including the price of the gratis dessert, and so help him, if Ardath ever projected her pricey presence onto La Lune and ruined this place in some misguided sense of charity toward her brother’s favorite restaurant, Procyon swore he’d go into mourning.

Not that the staff would be sorry for a rise in tips. Maybe crashing dishes and no music in restaurants would be the new fashion statement. Maybe there’d be a new chic, for the slightly distressed environment.

But Procyon doubted it. Any new ownership would fire the staff for breaking the crockery, and they’d install that damned Rhythmique apparatus, grim thought, to pound rhythm into the floor. Then they’d triple the prices of the food, advertise up and down the street, and it just wouldn’t be La Lune anymore.

Damn, damn, and damn. He should call Ardath and absolutely threaten her life if…

“Staff alert.

“We have an Earth ship inbound for docking. You may have noticed.”

That was loud. Impossible to ignore, blasting through the tap. He’d stopped dead on the walk, as if he’d been hit with a stun, and recovered, trying not to be conspicuous.

Brazis himself. The voice always sounded different coming over a tap, the way people didn’t naturally know what their own voices sounded like outside their heads; but it was Brazis, from the inside, Brazis, talking to the whole staff, no matter where they were, and Procyon looked stupidly toward the ceiling of the corridor and its bright lights. He hadn’t known there were secure tap relays all the way to the bag end of Grozny.

But of course there would be, now that he thought of it. Brazis had his agents working in all sorts of places where trouble might hang out. They had to have some way to report in, off the common tap. There might even be secure relays on other levels of the station, for all he knew, wherever Brazis might have interests.

“Be discreet. Stay out of questionable places.”

Did La Lune fit that description? Intrigue wasn’t his forte.

“Best if you could all stay in your residences the next few days. Take this very seriously.”

The old man seemed actually worried. An Earth ship was coming into dock, and they were supposed to go home, pull the lid on, and stay there.

All right. That was a clear and sobering order. He started walking. Home it was. No show. Eating in and living in for a few days, he could do that. He could stop by the store and pick up a few items, and he’d be fine. He certainly didn’t want any trouble with admin or the old man, and reality had just jolted into his path, with an advisement that had to include police and everybody associated with the Project, a regular take-cover, as if there were something going on that threatened all of them.

But insatiable curiosity was his profession. He wondered what unprecedented thing was going on, involving this ship from Earth, that produced this kind of order.

He dipped into the common tap for the moment, wondering if there was any sort of news bulletin he hadn’t picked up. But all he heard was talk about a garden show, and a new music shop opening on second tier. He shut it down and cast an eye to the running newsboards as he walked Grozny toward home.

The Earth ship was coming into dock in the slow way ships did. Whatever it was, it would be here by morning.

The rich dessert wasn’t resting quite as easily on his stomach. His world was running so very well. Change wasn’t good. Any change at all in things as they were wasn’t good. He didn’t want any Earth ship bringing emergencies and take-covers without any rumor what was going on.

Cheese. He was out of cheese and pasta makings, his standard recipe for domestic survival, in a fancy kitchen synthesizer woefully basic in patterns, since he’d never really used it for more than caff and breakfast.

Maybe he’d stop by the store and get one of those frozen cakes the store sold, from its own kitchen. That would fortify his spirits in his hours locked away. And it wasn’t as if he wouldn’t hear things: he’d gotten news the rest of the station hadn’t. The Project would keep him informed. He’d hear something more, surely, when he went back on duty tomorrow morning.

But he was in confinement, otherwise. If there was a parental potluck, he was assuredly going to miss it. That was a plus.

He shouldn’t answer any calls. And his mother would, of course, call, and then worry that she couldn’t get to him.

He should send her a note—his religious mother not, of course, having a tap—he should send something casual, like a card, to forestall her questions. He could send a courier note from the grocery.

Short and sweet: Dear Mum and Dad, extra work at the office. I’m on mandatory overtime, a computer blowup.

So they wouldn’t possibly connect it with the inbound ship.

Wish I could be there. Congrats. Love, Jeremy.

Damned good thing he’d sent the crystal egg.

HOME. THANK GOD, Reaux thought, home past the cameras and the media hounds with a well-rehearsed statement– we have an ambassadorial visitor, and expect a brief visit and consultation—then safely, solitarily, home. The smell of Judy’s grilled fish permeated the rooms as he hung his day coat in the closet. He hoped for scalloped potatoes. He hadn’t had potatoes in forever.

And a glass of white wine. Maybe two glasses. It had been a day. It had been, he remembered, twodays. And he was home. Safe.

The ship was on approach now, for docking at about 440h. It had become tomorrow’s problem. Tonight his wife had decided to cook, and thanks to that decision and a small crisis with a beautician, he had the privacy and comfort of his own well-secured walls around him, instead of a restaurant where the media might insert a lens in the table bouquet. It damned sure beat takeout and a nap in the office for a second night. Whatever Judy’s personal reasons, whatever fuss she was having with their teenaged daughter, it was a very good night for her to have resurrected her culinary skills.

He found her in the kitchen, in an apron, pushing buttons on the grill and looking domestic and frustrated, her meticulous coiffure a little frayed. He came up behind her, having gotten half a surly glance, put his arms around her—still no yielding—and kissed her cheek.

“You can pour the wine,” Judy said.

He saw the wineglasses—two—on the white tile counter. He pressed keys on the fridge: it delivered the chilled wine, and he slipped the bottle under the opener. Hiss and pop, as the wine began to breathe.

Wonderful sound.

“Pour it,” Judy said. “Pour me one.”

Not good. Not celebratory, that was sure. He poured two full glasses and handed her one.

“Our daughter,” she began.

“Dye didn’t solve it?”

Mistake. Judy took a deep, angry breath. And took a large gulp of the expensive wine before she set the glass down on the counter. Thump, face averted, both hands flat on the counter. “Setha. Setha, yourdaughter—her friends—her friends, Denny Ord and Mark Andrews…”

“I know them.”

“Clearly you don’t know them well enough! They’ve been arrested. Swept up in a Freethinkers’ dive down on Blunt!”

A moment of panic. “Kathy wasn’t involved.”

“Kathy was with me.”

“Good.” Deep breath. “Good sense of her.”

“Do you understand me? Our daughter has friends in jail.”

“They’re both from good families. I’m sure they were doing what all young people do at one time or another, slipping down to the Trend. She wasn’t involved in it, and their parents will get them out of their mess. It’ll all pass.”

“I want some support, Setha! I want some backing here!”

“I’m sure I’ll back whatever you think needs backing, but I’m operating on short information, at the moment, Judy. She wasn’t with them, and I’m sure the boys haven’t done anything but be in the wrong place. It will all work out.”

“You don’t understand!”

“I know I don’t understand, Judy. I’m asking for information.”

“Her friends,this Denny and Mark…I’m forbidding her to associate with these people. Forbidding her even to speak to them, ever again! I want your backing in this. I want her school sessions changed! I want her to transfer to St. Agnes!”

“That’s a little extreme, isn’t it? If you haven’t seen the news, Judy, a lot of people are getting swept up on Blunt at the moment. Nine-tenths of the people hauled in may be innocent, maybe even just passing on the street, and nobody’s even going to notice if two teenagers got into the sweep. There’s a security watch on. They’re pulling in everyone who’s anomalous down there, no proof these boys are actually guilty of anything at all but bad timing. I certainly don’t think there’s any need to pull Kathy out of a school where she’s happy.”

“She’s running with the wrong people, Setha! She bleaches her hair, her friends get arrested—three guesses, Setha, where she was supposed to be today, when she didn’tget arrested! With them! I’ll bet, with them!”

“Judy, proportion. Proportion.”

“She’s cut sessions before now to go down there! Did you know that? She’s cut three sessions this month, and the school didn’t report it, because theydidn’t think it was significant, and I just happened to see her attendance record when I excused her out today to get her hair done! That’s what’s going on, Setha! I can’t quit my job! I refuseto quit my job because I can’t trust my own daughter to be at sessions without checking up on her every minute! If I can’t trust her to go to sessions or to be home when she’s supposed to be home, what can I do?”

He took a deep swallow of wine himself. “We can certainly have a talk with the school administrators about their reporting policies.”

“I stayed home from work today. I had Renee come here, and I made it abundantly clear I didn’t want this bleach job talked about in the shop.”

“Did it work? The dye?”

“It’s at least better. And then when Renee left—Have you seen Kathy’s closet?”

“I—no.”

“Things that don’t fit decently, low cut blouses—she’s asked me for clothes money three times in the last month, and what she buys is a disgrace, an absolute disgrace, Setha! Sweaters down to here.” A measurement low on Judy’s own elegantly bloused bosom. Which generated a grease stain on the mauve silk to which Judy at the moment seemed oblivious. “Pants that show everything! Shoes you can’t walk in! Tees with crude language and shorts that wouldn’t make decent underwear! I took her shopping after Renee finished.”

“That sounds like a good thing.”

“I took her to lunch. We had a perfectly nice lunch. Then I took her down on Lebeau, to Marie Trent’s.”

Judy’s favorite shopping venue, where the establishment brought outfits out one at a time, modeled on live mannequins, and served tea while the systems constructed your purchase to fit your own physique and your own coloring.

“What did we spend on this venture?”

“Plenty! Her hair styled, a manicure, and Jeanne Lorenz jewelry. And then she didn’t want the clothes once they made them. Marie Trent herself tried to explain to her that she does have too much bust and she could stand a little sculpting, and meanwhile she should deemphasize that feature with a perfectly beautiful look for her. Kathy said to Ms. Trent’s face that shecould do with bigger breasts and her shirts all looked like sacks. At that point, Ms. Trent said I could take her out of the shop, and I tried to, but Kathy threw a fit, a screaming fit,Setha! I was so embarrassed. I’ve never been so embarrassed in my life. And Kathy wouldn’t leave the shop. Kathy kept saying, quote, no bitch could throw her out, and nobody could talk to her that way, and that she was your daughter…”

“God.”

“Oh, yes, yourname got into this. Now, are you worried? Kathy said she knew grotesques on Blunt with more taste, this, when another customer had come into the shop! Ms. Trent threatened to call the police.” Judy was shaking. She picked up the glass and almost slopped the wine over the rim getting another sip. “I can never go back there, Setha. I can never go back there. I don’t think I ever want to leave the apartment again in my life!”

“Judy.” He did feel sorry for her. Glass and all, he put his arms around her. “You have to go back there. Tomorrow. I’d advise an apology to Ms. Trent and a very large purchase. Break the budget.”

“I don’t know why Kathy’s acting like this, Setha, I don’t understand it!”

“I’ll talk to her.” At the moment he had Judy in his arms and a wineglass precariously crushed against her bosom. He disengaged carefully. “Are you all right?”

“I need you to be home and deal with this!”

He was suddenly aware of a burnt smell. “I think the fish is done.”

“Damn!” Judy burst into tears and grabbed the oven door.

“I’ll talk to Kathy.” It was an escape. Judy was about at the screaming stage herself, and it didn’t do to push her to communicate. As Judy should learn about Kathy someday, except they were too much alike. Two queens couldn’t possibly sit on the same throne.

Cutting school sessions and sneaking out into the real nether-side of Blunt, however, was a serious matter. A screaming fit in Marie Trent’s was serious on another level, an exposure to gossip that did his wife and daughter no good, and him no political good at all under present circumstances, with the media on the hunt and frustrated. He’d better call Marie Trent’s himself, apologize profusely, and buy something extremely expensive for Judy, trusting Marie Trent had Judy’s sizes in the computer.

He could do all these things afterhe’d dealt with Mr. Andreas Gide, tomorrow morning, assuming the ambassador’s ship arrived on schedule.

God, Judy and Kathy could time things amazingly. One night he spent at the office, and they were immediately at each other’s throats.

He took the lift up to Kathy’s hallway, walked to Kathy’s door. Hesitated. Knocked.

“Kathy. It’s your father.”

“Go away!”

“Kathy, I’ve got a ship from Earth on my doorstep and your mother’s burning supper downstairs. We need to talk.”

“No!”

“I heard about Marie Trent. I sympathize with your position and I’m not sure her clothes are your style, but can we possibly avoid stationwide media coverage?”

A heavy thump. Something hit the wall. Little thumps then as bare footsteps marched to the door.

It opened. Kathy stood there flatfooted, a beautiful teenaged girl in a gray, too-old-for-her skirt, a chic white silk blouse half-unbuttoned and hanging its tail out to the left, and her hair an unKathy-like and shocking red-brown, with her olive complexion. Behind her, the closet was a disaster area, clothes, mostly black and gray and white, flung over the bed and onto the floor, along with a confetti of fabric bits on the floor. His daughter’s chest was heaving. She had a scissors in her hand.

“She threw out all my clothes and put her damned castoffs in my closet!”

He heaved a sigh. “We’ll find your old clothes. Put down the scissors.”

“She says she put them in the disposer! Those were my favorites! She hates me! Everybody hates me!”

“Damn. Look, Kathy.” He put a hand on her shoulder. Kathy flung it off, a hazard with the scissors. He took the implement out of her hand, reached in his pocket and extracted his wallet, and now that he had her slight attention, drew from that mesmerizing object a credit card, holding it up between them. “Kathy, I’ll give you five hundred on my card. Just go buy something on your own tomorrow, without your mother. I’ll excuse you out of sessions.”

Five hundred had secured his daughter’s solid interest. She wiped her eyes and took the card.

“I just don’t know why she can’t leave me alone.”

“I’m on your side, right down to the point you cut your sessions, which is in the school records. On that score, I have an objection. Cutting up your clothes…I can almost sympathize with that. They don’t suit you.”

“I hate them!”

“The clothes? That’s evident.”

“The school. The damned school! I hate them, too!”

“Don’t use that language, please. What’s the trouble?”

“They’re a bore, and they’re always finding fault, no matter what I do.”

“Ippoleta Nazrani?”

“Is a skinny-ass whore.”

“Language. Language, Kathy.”

“Mignette.”

“Pardon?”

“I want to change my name. I want to change schools.”

“Why?”

“I’m bored. I’m bored, bored, bored, boredwith those fools.”

“Boredom rather well damns your own imagination, doesn’t it?”

“I don’t care. I don’t like always having to watch what I do, watch what I say, all because Ippoletais so good and so sweet. She’s a lump. She’s just a lump. She’d wear these things! I won’t!”

“Kathy.”

“Mignette. I want to be Mignette. It’s what my friends call me.”

“Mignette.” It was always something new with the female of the species. She wanted to change her school and change her name. As if that would solve it all. “I hope I’m still your father.”

“Mother’s not my mother.” A furious kick at the detritus of fabric snips on the floor. “Not anymore! And I haven’t got anything to wear and she says I’m not to talk to Denny and Mark, who are the onlyintelligent people in my whole class. And she embarrassed hell out of me with this stupidhaircut and this stupiddye job and I have to go out in public and have that stupidwoman tell me I’m fat because I have a chest and she doesn’t!”

“You know, Kathy—Mignette—I completely sympathize about the remarks. But you can’t pitch a fit in your mother’s favorite shop. She took you there because she cares about you and she wanted to give you what she thinks is pretty.”

“She took me there because she thinks I’m fat, too, and she doesn’t like my clothes and she hates my friends and she’s thrown out all my stuff, and she just drives me crazy,papa, she just drives me crazy!”

Now it was tears. Hormone wars, he’d about bet, fiftyish wife and teenaged daughter, who physically took after his side of the family. He gathered his outraged daughter in his arms and hugged her hard. “There, there, Mignette or Kathy, you’ll have five cee to go fix this tomorrow. You’re a good kid. You manage pretty well, all taken together—you don’t do drugs, you don’t do illicits, you usually don’t do things that I have to explain on the news and I appreciate that, I respect it, I really do. You can just come by the office tomorrow when you get through and show me what you’ve bought. And I’ll talk to your mother.”

“She’s not my mother, I tell you!”

“I’m afraid you’re stuck with biological fact, darling girl, you’re hers as well as mine, which is why you’re always fighting with each other. I want you to wash your face, tuck your shirttail in, and come downstairs.”

“No!”

“You can’t starve. I’m sure it’s a lovely fish, even a little singed. Just be my sweet daughter and learn to be a diplomat.”

“I don’t want to be a diplomat.”

“What doyou want to be someday?”

“I want to be rich, and buy anything I want and not have to be polite to anybody.”

“I’m Governor of Concord, and I absolutely have to be polite to everybody. Money and power won’t do that for you, Kathy-sweet. Mignette. Nothing ever excuses rudeness. Not yours and not your mother’s, and I hate it when you do this to each other. Temper always makes a mess of your surroundings, and if you’re smart, you mop it up as soon as you know about it. Now go wash your face. Put on your robe, if you don’t want to wear what you have on—I trust your bathrobe survived the scissors—and come down to dinner and be nice to your mother.”

“I can’t!”

“Katherine Callendish-Reaux, you will. You can and you will. Listen to me.” He set her back sternly, hands on her shoulders. “I have a headache. I have a backache. I had a cold supper last night, damned little sleep in my office chair, and interviews all day with every power broker on Concord, from Station Security to the Outsider Chairman. I’ve had an absolutely hellacious two days, I’ve got an ambassador from Earth arriving tomorrow, and he could conceivably decide I’m not to be governor anymore, and you’re not to have a nice apartment or any nice clothes, or any father for that matter, do you understand that? That’s how serious it is. So if you’ll do me the moderate favor of giving me five days of tranquillity in this household, no matter what you have to say or do with your mother, I’ll be so deep in your debt I’ll buy you a shop full of whatever your heart desires and let you dye your hair blue if you like. Just hold the lid on for five days. Please, baby.”

“Mignette!”

“Mignette.” In calm, perfect earnest. Hormones were raging, no question. Not a word he said got through. Or would, until the adrenaline ebbed. “Come on. Tuck it in and come down to dinner. Your mother will be vastly relieved.”

“I don’t want her relieved about anything.”

“Come on.” He knew his timing. He set a hand on his daughter’s back, steered her out the door. “Shirttail.”

She made a one-handed, halfhearted shove at it, and slouched ahead of him down the stairs barefoot.

Judy had the table set. Table, yet. It was a once-a-year occasion, table-setting, never mind the fancy inherited import china. Judy looked sidelong at her daughter and forbore a comment.

Good, he thought. He pulled back a chair for his daughter at the side of the table, pulled back Judy’s, at the end, and they sat down to a still-passable grilled fish.

They were a family tonight.

Maybe it was auspicious for tomorrow that, within the household, his diplomacy had prevailed.

GROCERIES. The essentials. A frozen cake, imported chocolate. Heavy synth packets that he had to have for pasta and cheese…well, and some fancy bread, which looked good. He could have called it in and had it all delivered, but deliveries had a way of showing up when he was locked away downstairs in an office Brazis didn’t want advertised to local merchants; and if he didn’t get the delivery when it came, he’d have a message requesting a time for redelivery, which wouldn’t work out any better. There were a lot of conveniences on Grozny that just weren’t convenient, if you lived only a block from the store and didn’t rule your own communications on the common tap.

A little déclassé to be lugging one’s own groceries, his sister would say. But she wasn’t here to be embarrassed.

And in-person shopping always turned out to be more complicated than phoning in. He wasn’t good at resisting nicely displayed treats. Last-moment packet of custard cups. Patent really grown berries from Momus at 29.95 the box. He was feeling sorry for himself.

His bills were paid up, his messages were all answered, every day. It was going to be just him, the kitchen synthesizer, and the echannels for the next several days of enforced solitude, no questions asked. Grim.

He ran his items down the track, stuck his card and his hand under the reader to pay out, then hefted the heavy green bags, careful not to crush the delicate berries, and headed out.

Straight into public view—public suddenly meaning a handful of faces he’d ever so rather not see.

Algol was an old Stylist, verging on a grotesque. The left side of his face was black, the right side red. The designs that ran between were very nicely done. That effect was what saved him and made it art…but there were whispers of an illicit gone way wrong twenty years back that had had to be covered up very expensively, and that had left certain sexual side effects.

Not so Algol couldn’t muster a coterie of hangers-on—tough sorts, the sort you’d shy away from during the odd hours on Blunt, which was where they usually hung out.

He didn’t want this encounter. But he clearly had it.

“Little dog.” That was Procyon’s namesake star in vulgar terms, lesser Dog Star after the Hunter, as Earth saw the ancient sky. Algol was very educated, a walking encyclopedia of bits and tags. But the split defined his personality, too, bi in every department. “Hunting what, little dog?”

“Box of milk.”

One of the hangers-on stepped into his path. A second and third blocked him in, little punks trying to prove their usefulness to the center of their universe.

“Procyon. Procyon who works for the big dog. What does Brazissay about this ship?”

“Somehow I don’t get that information.” If the punks started a fight, he supposed he just had to take it and hope the store called the cops to save him. Brazis didn’t like government employees, especially taps, throwing punches or getting arrested, and he’d now been way too many hours awake and had his nerves too jangled to put up with this. “There’s a ship. That’s all I know, demon prince, and I got it off the reader-boards. What have you heard?”

“Not a thing. Not a thing, little dog.” Cheap theatrics, Algol moved a hand and the flunkies opened out.

He didn’t bolt. His life was secrecy. He was appalled to hear Brazis linked to him—but maybe Algol meant it only in the general sense, in that he worked for the government, hence the Chairman. He tried for information. “Come on. You’ve heard something. Think it’s the governor’s problem? That arena business?”

“Not a sure word on the street,” Algol said. “Brazis’s snoops raided Michaelangelo’s this evening, just walked in and threw everybody out. Does that possibly say something to those in the know? Those who work in government offices?”

Michaelangelo’s was the chief Freethinker digs. Hisold digs. And Algol’s. God, did Algol think his job was with the slinks? That he was an informer?

“Somebody in Michaelangelo’s wasn’t what they wanted, after all, that’s what it says to me, and they went elsewhere. I wouldn’t know. Go home, why don’t you?”

“Word is Reaux’s dogs and Brazis’s slinks are out together in plain clothes, and they’ve ordered the untidy questioners of authority out of sight, out of mind. Callisto’sdisappeared.”

“Oh, well. They’re just picking up fools, then. I wouldn’t worry. I wouldn’t stand on the docks with a placard saying Freethinkertonight. I wouldn’t and you wouldn’t, and I’m sure they’ll let Callisto out someday.”

“Michaelangelo’s is closed to nonresidents for a week.”

That was unprecedented. “Interesting.”

“There’s a sign in the window. Somebody’s already flung paint on it.”

“Then it’s probably a good place to stay away from. Paint clings.”

“No sympathy at all from you for your old friends, little dog?”

“None for fools. I don’t intend to go down to the docks to protest Earth rule. If some do, they can look to spend a few nights behind locked doors, and I’m not going to protest that, either, when it happens. I like my own bed.”

“Your own lonelybed, little dog.”

“My nice safe bed, demon prince.” The sacks were heavy. He shifted them in his arms, a defense, a weapon, if it came to it. “My loss, I’m sure, but I’m happy enough. I wish I knew what was going on down on Blunt, too, but I don’t.”

“What’s going to go on, little dog, is a protest. The Chairman thinks he can shut down Michaelangelo’s, and shut down businesses he doesn’t like. The people are going to rise.”

“The people are going to get their cards ticked, if they get caught. Here’s a piece of my advice, for free. Stay out of trouble.”

“Never.”

“Well, at least I wish you luck. I hope the cops miss you—unlikely as that seems.”

“Coward. Slink.”

“Not a slink. Prudent, demon prince. Innocent, and planning to stay that way.”

“Little dog’s scared.”

“Little dog’s just going home. Good night, good luck, and don’t get caught.”

“So kind.” Algol waved an arm, letting him pass. “Run home. Run home. No need for the police ever to arrest little dog. He arrests himself. Is thatthese huge sacks of groceries?”

“Hunger pangs,” he said, and escaped, with predatory eyes on his back.

Well, if you wanted the official line, read the newsboards. If you wanted to know the craziest rumor on the street, ask Callisto; but if you wanted the best and most accurate, you went to Michaelangelo’s and just sat and kept your ears open.

Which now the slinks had shut. A week’s shutdown, arrests, and the problem ship hadn’t even docked yet.

He arrests himself.Not quite, though it stung. And he didn’t like it that Algol came to himasking about Brazis. He’d put it out that he was what he’d applied to be, a computer tech, not admin; and damned sure not a slink for the government. The street apparently questioned his cover. And what the street questioned—God knew, it could be serious trouble for him and his residency here if the light stayed on him too long.

He wanted to get home and become less conspicuous. Out of sight, out of mind, and he planned to stay far out of that one’s mind.

Maybe, too, he should report in to the PO and say he’d been approached by a questionable source, but he didn’t want to target Algol to get arrested—Algol and others might make that connection with him, if that should happen. Algol might well be one of the prime police targets already, and he didn’t want word running the street that he’d ratted Algol—God, no. He liked living.

He headed into Grozny Close, where his own neighborhood security cameras checked him out, where the likes of Algol and his muscle didn’t dare come, if they were half-smart.

He began to realize he was holding his breath. It came short as he let it go. His grip on the packages was iron, threatening to crush the fragiles.

He reached his own door. Entered. Sam lit the hall and silently lifted him to the heart of his own safe, secure apartment.

He dumped the sacks on the kitchen counter, threw the few frozens into the chute and let Sam read all the labels and organize things in the freezer and the Synthomate. The off-program boxes needed more attention: he had to be coordinated enough to scan the labels through the hand reader and coordinate them with their data, a fussy job, but there shouldn’t be frozens in that lot. He decided he was too tired and too frazzled to tackle the other sack tonight, except to send the fragile berries—they had survived—into the vegetable storage unit. He left the rest of the sack sitting on the counter and flung himself down on the couch, to sit and stare blankly at the entertainment unit—not to turn it on, just to stare at the wall-sized screen, letting the past hour play in his memory.

He didn’t want music, he didn’t want images. He just wanted to let all input channels rest a moment before he even thought about hauling himself up to bed.

Damn, why did Algol come to him to ask about Brazis’s intentions? That chance word had thoroughly upset his stomach.