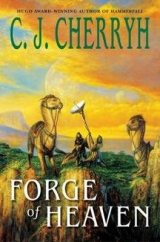

Текст книги "Forge of Heaven "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 30 страниц)

They had not overtaken their fugitives, who had remained elusive and skittish with the weather. Cloud covered most of the sky now, flashing with lightnings, rumbling with thunder. The prospect of the oncoming gust front was what had persuaded them they should drive down the deep-stakes in the last of the light and take what rest they dared. The strange smell on the wind increased with surface air sweeping out of the west, a smell like old weed, wet sand, heated rock. It would be a blow. It would be a very strong blow.

“He is injured, whether by the goings-on with this man from Earth, or by the Ila’s recklessness.” He was angry at the entire situation. He clenched one hand over the other wrist, arms about his knees, gazing out into the murky distances of the basin below them, the spire-covered descent of sandstone terraces. “I will try again before we move.”

The beshti, double-tethered with deep-irons right beside their sleeping mat, grazed on sweetweed that grew in a drift of sandy soil, as content as beshti could be, in this isolate, dangerous place, with the skies muttering warnings and the wind rising.

Their legs ached from their long, generally downward ride, constant jolting against one bracing leg or the other. It should have been a profound relief, too, finally to reach Procyon and prove that he was alive.

“Perhaps we should tell Ian,” Hati said. “If not Brazis.”

“Neither,” he decided. “Neither, until I have some indication where his safety may lie. He claimed he was going home, which by no means sounded safe, if enemies were looking for him. An hour, he said. Now the contact fails. Perhaps the weather. But we have nothing from him. We have nothing from Ian.”

“Husband, we have to look to ourselves. Time to go up.”

Events pressed hard on them. They had come within hearing of the herd, and lost them. They camped now right at the crest of the rocky slant that was the herd’s last and most frustrating escape. Contact with the Refuge had gone. Their terrace was broad and well away from overhangs, which protected them from quake. But that was not saying what layers of soft sediment underlay it, and what the rain might do.

Worse, they were about to lose the tracks, once rain came coursing down the myriad channels that laced across the slopes. They might pick them up after, in wet sand, but that was hoping the rain would stop before the flood overtook them.

“Shut your eyes,” Hati said, hugging him in a little shiver of the earth, so slight even the weary, feeding beshti were indifferent to it. “Rest for what time we can, and hope the fog holds off. If we have to climb in a hurry, we climb, and hope the fool beshti out there do the same. The boys will meet us up on the ridge. For now, rest. We have done all we could. We cannot fight the rain. Shut your eyes. Half an hour. Then we climb out of this.”

He put his arms around her and they lay down together, he lapping his robes across her, and hers across him.

In the dearth of information from the heavens, who alone had a comprehensive view of the situation, it became the only sane choice: get as much rest as they could before the weather turned, then pack up and climb back to relative safety. They would have to find the boys and walk down off the ridge, at the best speed they could manage, with their two beshti to carry canvas and supplies.

They might see their new sea. They only hoped not to see it yet.

11

THE HALCYON SAID it didn’t take credit cards, which was just crazy. Every place in the universe took credit cards. But the Halcyon said it didn’t, wouldn’t, or maybe the manager just meant this card, which could be risky to raise a louder fuss about, Mignette thought, if her father had finally put a limit, or worse, a trace, on it. So she shut up, near to tears.

She was tired, she’d had a drink, she felt a little sick, and scared, and she and Noble were going to do it together if she could get a room at all, which at this point didn’t look as likely as before. Michaelangelo’s had turned out to be shut to anybody but current tenants. She was sure her father had done that, likely looking for her and making an untidy amount of noise about it.

That meant all the people that might have been partying late at Michaelangelo’s, where they were supposed to meet Tink and Random as a last resort, were all scattered out all up and down Blunt, maybe competing for other rooms, which could mean there weren’t that many to be had up and down the street. Someone said all the other places with rooms had raised the single night rate, because of Michaelangelo’s shutdown. And they’d only found this one room, here, in a place they ought to be able to afford, a place that wasn’t too dirty, and now the stupid asses who ran it decided they didn’t want to take her card. She just wanted to scream, and didn’t dare. It was only her self-restraint that brought her close to tears. It was pure temper, and the effort not to curse them up one side and down the other.

They had no actual cash, she and Noble. She’d never handled cash in her life, beyond a few chits for street fairs, and here she and Noble were trying to have their romantic night, which was supposed to be so special, and now she was so upset from arguing with a fool with disgusting cologne about a not-very-good room that she felt like throwing up. Now Noble was mad about the room situation—he was scowling and looking off at the bar, with his hands in his pockets. He was about to sulk and get rude to everybody around him, she saw it coming, and he had no sense when he got mad. He scared her.

Desperate, she left Noble and went back to the front desk to try again. “We’ve just got to have a room,” she said, and burst all the way into tears. Tears sometimes worked. They did with her father.

“Well, I could do something for you,” the man at the desk said, “if you do something for me.”

“What’s that?” she asked, and the man got off his stool and moved over to the office door.

“Come in here,” he said.

She was stunned. “No!” she said, not half believing she’d just been propositioned by an old man in a cheap sweatshirt. She was outraged. Her face burned.

“Then get out of here,” the man said. “Out!”

She was embarrassed to death to be crying in front of this man. “Come on,” she said to Noble, and he still stood there like a lump with his hands in his pockets. She grabbed his elbow hard and tried to pull him out onto the street. He stood like a piece of the scenery and resisted going anywhere, being an ass.

“So what are we going to do, walk the streets all night?” he asked her.

She was furious. “I don’t know what we’re going to do, but I’m not going to sleep with that pig to get us a room!”

Noble took his hands out of his pockets and looked back at the front desk, as if he’d just waked up to the world.

He didn’t, however, offer to go back to the desk and beat hell out of the pig.

“So where are we going to go?” he asked her.

“Well, you don’t blame me, do you?” Her face had gone embarrassingly red, she knew it had, and people were staring at them, watchers all around the shadowy lobby with its imitation plants and its imitation wood. They’d become the show of the evening. People were sniggering. “They don’t take cards, they won’t talk, and when my father hears about this, oh, I promise you, that bastard is going to be looking for a ticket to Orb!” She said the last so the bastard would hear, but when she turned around, dragging Noble toward a dramatic exit, she ran straight into a living shadow, one of the Stylists, it had to be, that she had nearly bumped into. One of the beautiful people. Her embarrassment was complete.

“Well,” this vision of beauty said.

Male voice. Silken voice. The face was red as blood on the left side, black as space on the right, with tendrils wandering actively between. The eyes glowed with red, inner fire.

And this person, this Stylist, took her hand and held it, a warm, a wonderful touch. “A genuine damsel in distress.”

“Just a little trouble,” she said shakily, letting go of Noble. She was unwilling to admit to this vision what an embarrassing financial trouble they were in—out of money and out of ideas.

“Do you need a place to stay tonight, lovely?”

“Myself—” She didn’t want to admit to this gorgeous creature that she was attached to the sullen, unstylish teenaged lump sulking behind her with his hands in his pockets, but she had come here with Noble and she found herself standing by that fact. Maybe it was a sense of honor, even if it drove this gorgeous being away. Maybe it was fear. Noble was her safety, her barrier against transactions she didn’t altogether understand. She said shakily: “ Andhim.”

“Oh, well. One, two, no difficulty.” An ink black, fire-shot hand lifted to brush an airy touch across her cheek. “He can come along, too. But who are you, pretty thing?”

“Mignette.” A Stylist thought she was pretty. Her heart raced, fluttered, raced. “I’m Mignette. He’s Noble.”

“Algol,” her vision said, and flourished a gesture toward the outer door.

She walked with him out onto the street. Noble slouched along at their heels.

“An inconvenience, this disturbance up and down the street,” Algol said, “but not to those of us with forethought and connections. You tried Michaelangelo’s.”

“It’s shut,” she protested.

“Oh, not to those of us who live there. You’re new to the street, aren’t you?”

She had to admit it. “I just arrived. Noble and I—”

“Oh, well, and the police have to show their authority now and again, darling girl. It’s this Earth visitor that has them buzzing about. But their orders don’t apply upstairs, to private apartments. Dear girl, we who have the keys to the place do as we please. We always have, always will. Such pretty eyes you have.”

The contacts were just commercial, off the rack. She didn’t feel constrained to blurt that out. She looked really good. She hadn’t known how good. Her heart skipped and danced as they walked, together, in beautiful company.

Algol led them not to the front of Michaelangelo’s, but around the side of the frontage to the service nook. She was uncertain that was safe, until she saw a delivery door.

He had a key.

“We’re supposed to find Random and Tink,” Noble objected from the background. She knew it wasn’t Random and Tink that concerned him. Clearly Noble didn’t at all like the way things were going. He would rather strand them back on the street with no place at all, than take help from a source that cast him in the background. But she didn’t pay any attention. They had a personal invitation from a Stylist, and a place to go that had real cachet, and she wanted to go where the beautiful people went. She hadn’t deserted Noble. She’d kept faith with him. So he could be mad for an hour. This was important. A prince of the Trend had swooped down for a rescue, because of her. This was a way into a rarefied society.

She stepped through the door that Algol opened for them, and Noble had no real choice but follow.

A LIZARD WATCHED a gnat, bubble-world confrontation above a rotting flower. Reaux, late-night in his office, watched the lizard, distracting himself as best he could from the quandary he had landed in, trying to have caff and a long-delayed sandwich in peace. Jewel was in one outer conference room, silent the last while, fed and supplied with reading material, concealed from any officials who might come and go.

Since Brazis’s warning, he no longer dared rely on Dortland—nor dared he rely on Brazis, entirely. He had his own heavily paid plainclothes guard sitting watch on Gide.

Gide’s associates on the Southern Crosswere asking hard questions about the attack, and he had had to admit that there was as yet no word on Jeremy Stafford. So he said—while hoping there wouldn’t be.

Dortland’s men were watching Stafford’s parents. He couldn’t pull Dortland’s whole force off the search for Stafford without rousing suspicions and getting thatfact reported to Earth—very directly so, if Dortland was talking to that ship on secret channels. But he had two others of his own bodyguard, men who owed nothing to Dortland, watching down on Grozny, too, with no success yet in finding Stafford. Tracking anyone in the Trend tended to meet with resistance and deliberate misdirection. There were sightings. There had been three. But they didn’t pan out.

Find my daughter,he’d asked Dortland personally, hours ago, when he’d gotten him on the phone. There’ve been new threats.Never mind the threats were from his wife. I want her back. Now.

Kathy was the best distraction he could offer, and he felt more than guilty doing it—as he felt guilty and frustrated in distrusting Dortland on Brazis’s say-so. He felt ashamed of his current situation, and scared, increasingly isolated in the exercise of the power he did have, wondering even what Ernst thought of the orders that had come out of his office.

And increasingly he wondered, now, whether he would find Kathy before something disastrous happened…before he got a call from some hospital…or before she became a pawn in this covert maneuvering of powers Kathy had no idea of.

To add to his troubles, that phone call from Judy. She threatened to go down to the streets and look for Kathy herself—the very last thing that would help the situation, and she had cried when he told her so. Judy was furious about the police outside the apartment. She was furious that he hadn’t dropped everything and come home to be with her at supper. She was doubly furious that he’d had all her calls routed to Ernst. “Not even to you,” she’d cried, when he had, in desperation and compassion, talked to her. And at a screaming pitch: “How dare you?”

Well, he dared do it, as other things, because he had no damned choice. What he prayed for was a peaceable end to this situation, one that involved Stafford somehow turning up safely where he belonged, so they didn’t have a blowup with Brazis.

And he prayed for a solution that didn’t involve Andreas Gide setting up what Gide would try to expand into a shadow government on his station. But in the darkness of the hour, it didn’t seem likely that he could prevent Gide trying it, and, despite his speech to Gide, he wasn’t utterly confident he could keep power out of Gide’s hands.

He wanted his former relationship with Brazis back, uncomplicated by Brazis’s confidences. He wanted things the way they had been. Until he had better information, he wasn’t sure he could trust anybody in the universe, even Ernst.

He rather thought of sending Dortland to Gide’s new office, tied up with a bow, with recommendations of employment, once this was all over and that ship left. But with Dortland wearing his right colors, he’d still have to ask himself constantly which ministers, which councillors were in Gide’s pocket—and those pockets, with every annual ship from Earth, could prove very deep indeed.

He could tell Gide privately that Dortland had engineered the attack. That might be interesting.

The lizard snapped his jaws in threat. The anoles never won. The gnats collectively never lost. System in perfect balance, as long as light came into the sphere and the temperature stayed moderate.

So had Concord been in perfect balance, for long, long ages. And did Earth or the Treaty Board itself think it was going to win something new if it came in here disrupting what worked just because some politician on the homeworld had a theory?

He saw the heart of the situation now: distrust had found a way onto his station, distrust of Brazis had moved Earth to send an agent here, Apex had sent an agent for the same reason, and to create their new trustable system—Earth now corrupted his agents, his office, his peaceful situation. No foreign assassins. None from Brazis’s office. He was absolutely convinced now that Gide’s arrival was a ploy, an elaborate, sacrificial ploy, unknown even to Gide, to land a Treaty Board office on his station and create yet one more power, one they hoped could override him and create trouble for Brazis.

And if Gide hadn’t had a clue what they meant to do to him, Dortland being behind the attack made an unwelcome sort of sense. The mobile unit was slagged, to tell them nothing. Gide was only slightly injured. There’d been a launcher in the garden, yes, and yes, there’d been a projectile from outside, but had it killed Gide? No. Could it have killed Gide? Unknown, without examining the machine before the damage its own security systems had done to it. But he doubted it would have. Everything added up to Dortland, who would have killed two of his own men. And that meant Brazis was telling him the truth, that Dortland was working to bring him down.

He didn’t want to believe it. He didn’t want to deal with it. He’d never wanted to play life-and-death politics. But all sorts of desperate thoughts had nudged their way from the nether side of his brain, where they now established a well-defined architecture and a set of connections.

If Gide had mistakenly died in the attack, Earth would bluster and moan and threaten, and ultimately do nothing about it, since, public face, Earth well knew the hazards of truly ham-handed interference in the Outside, and most specifically at Concord, of all places.

But if someone on the Treaty Board was reckless enough to insinuate an office onto Concord, it was clearly in hopes that their pretense of hysterics and self-protection would dissuade Apex and the ondatfrom objecting too much to a fracture of the very Treaty they allegedly watchdogged.

And if things had shifted this much in the Treaty Board, that body had a great deal to learn about Apex. It was very possible, if Apex decided to counter this move, that Gide would be dead within the year, Dortland with him, accidentally, of course, neatly folding the new office, an unnegotiated folding as it had been an unnegotiated establishment—and he’d have to explain it all to the next Earth ship that called. He could trust Brazis—enough, but not far enough that he was willing to be the first Apex-supported Earth governor in history.

If he let it all play out that way, he could be in for a rough ride. But the alternative was dire. He could well see Earth, under the aegis of what began to look like a newly partisan Treaty Board, begin to play a dangerous third side in ondat-human politics, or thinking to do so—possibly getting a presence onto more than one station, creating yet other offices to trouble governors all over Outsider space. If the Treaty Board had gotten actively into politics, no one on Earth stopping them, it meant Earth now didn’t trust the governors they themselves had put in office over unwilling populations in the Outside.

Apex had already spoken, via Brazis, a clear warning, hard, clear words.

Worse, they were undoubtedly going to hear from Kekellen once a report about this new office filtered through the translators.

God, maybe Kekellenwould nix the idea.

Now therewas a thought.

Apex would object to Gide setting up here—but Earth, who’d take anything Apex objected to as a very good idea, would think very differently if Kekellenrose up suddenly and objected. Earth had to count on Kekellen taking ages to understand something had changed. It notoriously took decades to negotiate any change of procedure with the ondat,in the delicacies and difficulties of translation, and while Kekellen usually ignored Earth’s small shifts in policy—this—

This might prove different, if Kekellen understood that what they did marked a change in Earth’s representation out here.

He was incredibly tempted to send his own message to Kekellen, now, before that ship left dock, both to pour oil on those dangerous waters personally and to urge Kekellen to protest before worse happened.

A dangerous, provocative move, to send a message to Kekellen without going through the experts. But his experts were, he had to recall, licensedby the Treaty Board.

Oh, that was nice. His translators were about to come under Gide’sjurisdiction, and operate at his say-so.

Notan acceptable situation.

What he contemplated, however—God, it was dangerous. The ondatcould take exception, take action, not even limited to Concord…

But it might be the most important act of his governorship—to protect Kekellen and the Treaty itself from what looked more and more like his overthrow and the establishment of a new Earth authority out here, at an outpost that meant the difference between peace and war.

What would he say to Kekellen, if he dared? What could he say to Kekellen, without overmuch abstraction, if he could gather the personal courage to risk his comfort, risk his life—risk his station’s existence, for that matter? He had a wife and daughter to think of. They had their home, their comforts. He would have the illusion of power lifelong, if he kept his mouth shut and minimized his interference with Mr. Gide, and Brazis, and all the likely agents in a prolonged power game. Or if he strung things along in a series of compromises…lose a little, gain a little, playing a tight and narrow game, surrounded by Earth-staffed agencies he could no longer trust…he might survive and keep everybody alive, if he used his head. It was a terrible risk, to take direct action. To talk to the ondat—

But he had the official translation lexicon, among the books behind his desk. His computer could arrange acceptable syntax, and it routinely did that, when he needed to skim an incoming message. If he just picked the words cautiously and kept to solid concepts…not going into the network to tip off the experts as to what he was doing…

The rest of the sandwich lay untouched. He stared at the bubble world, chasing thoughts through this and that maze of official protocols, and threat, and weighing not only the possibility of detection after the fact—but before it.

He could do it. He mightpull it off.

He could at least see if he could compose anything reasonable.

He surfaced his keyboard on the desk and made a cautious initial effort.

Reaux to Kekellen. Gide comes from Earth ship. Someone attacks Gide. Reaux thinks the attack is a trick. Gide wants power on Concord. Reaux asks Gide to leave, but Gide won’t go. Gide’s office on Concord will be rival Earth office. Concord needs your help to stop Gide.

The computer worked for a second or two with that input and came up with ondatscript, and a corresponding translation: Reaux to Kekellen. Gide comes from Earth ship. Attack on Gide unknown origins. Reaux says subterfuge. Reaux says Gide wants govern Concord. Reaux says Gide go. Gide says Gide not go. Gide makes hostile Earth office on Concord. Reaux says Concord wants Kekellen help, wants Kekellen stop Gide.

A little further editing. Get that word hostileout of there.

The computer digested it and spat up something he halfway dared put his name on.

Something that could absolutely ruin him if it got to the wrong hands.

God, could he even trust Ernst?

He ate an antacid. One of the twelve-hour kind. He didn’t rate himself reckless or stupid, and on one level, sending this message was beyond stupid, it was criminal. It put him and his family at terrible risk. It put the whole station, the whole situation with the ondat,at risk. Their weapons had taken out a planet. A space station, in their territory, was negligible. The end of everything.

But on another—what happened once Gide settled in? Could he even stay in office, once every enemy he had, Lyle Nazrani leading the pack, immediately threw their support to Gide and manufactured charges to bring him down and raise Gide to more and more prominence? He had organized enemies. He could see a challenge not just to him, but to the governorship, leading to the Treaty Board office de facto taking over, with Nazrani and crew power-grabbing all the way.

Which meant Apex would get involved, and then things would get dicey with Kekellen, just the same. With the same result, more slowly, more inexorably, with no way to claim it was a single mistake.

He had this one chance to nip the whole situation in the bud, a short, sharp action that didn’t let Gide’s organization, like contamination itself, spread through his whole establishment and create more Dortlands.

He had some confidence he knewKekellen’s reaction. If he could get the message through, and do it quietly. If it went bad—if it went bad, he could put himself on the line, say it was his mistake. His and only his.

What he sent certainly couldn’t go through the compromised phone system, wide open to that ship. They could stop his message cold.

For secure communication resources, he had Dortland. He had Ernst. He had a handful of hired guards who didn’t know the systems.

And he had Jewel. He had Jewel Sanduski, and he had Brazis. He couldget the message out, right under the Earth ship’s nose.

“Ernst?” He used the intercom. “Is Mr. Dortland available?”

“He left a written report, sir, and said he’d be back in an hour.”

One down. One out of the way.

“Bring his report in. And bring Jewel with you.”

“Yes, sir,” Ernst said, and broke off to do that.

Less than a minute and Ernst brought Jewel, and simultaneously laid Dortland’s report on his desk, for his eyes.

It said: Your daughter is reported to have changed her appearance radically. The bearer of her card was arrested within the last quarter hour but proved to be a female petty thief, who claims to have picked it up, dropped on the street.

The antacid wasn’t at all sufficient.

In the other matter, we have analyzed the shell fragments. The launcher is a simple tube, locally procured out of Concord Industries. The shell is more exotic, likely out of Orb, where several such attacks have been directed at law enforcement. It was imported. We are checking customs records.

Did he believe that? He believed Dortland already knew damned well where that shell came from.

We have recovered Stafford’s coat,the note said further. It shows residue of blood and explosion. We are checking the origin and integrity of the blood. We have six witnesses who put Stafford on Blunt Street traveling toward Grozny, and have agents in that area, but several locals have manufactured misleading sightings. This is common practice in that district when authorities seem to be tracing an individual. We discount these reports. The sightings we do trust are around 12th and Lebeau.

We have interviewed Stafford’s mother, who claims not to have heard from her son, and his father, who says as far as he knows young Stafford is in the Outsider office complex. We discount his report as ignorance of the situation, but have sent an official inquiry to Brazis. Other relatives claim no knowledge and assume Stafford is at work. The sister alone remains elusive. We have received massive disinformation as to her whereabouts and threats have been issued against our agents.

We have agents on guard in Ambassador Gide’s vicinity. He is reported asleep.

Also, one Gifford Ainsford Ames, aged 54, approached theSouthern Cross ramp claiming to have information about irregularities in the arena design selection as motive for the attack on Gide and asking for protection from pursuit, claiming your office has persecuted him. Medical records indicate he has evaded treatment for a mental condition for the last two weeks. Arresting officers have taken him to the hospital, and we have assigned an agent on that case for a concluding report.

Damn. He knew about Ames. An architect, and a cyclic depressive with a penchant for drink. His arena design hadn’t been accepted, and he’d thrown a screaming fit in the offices.

One part of his madly racing brain said damn, he didn’t want the word arenamentioned in Earth’s agents’ hearing; and another said fine, so let a lunatic pitch his fit on that topic on Earth’s threshold. Nazrani’s complaints, recorded with that ship, would lose credibility in consequence.

And Dortland stopped him. Which meant Dortland didn’t want that on record, either. So where was truth?

But at a certain remove—he didn’t care. He didn’t give a damn. He had had all the doubts his mind could hold. He had laid his course.

He looked up at Jewel, feeling himself inexplicably short of breath, about to do something he never could have envisioned doing. At a certain stage of his life he might have considered Judy and Kathy, but they had both distanced themselves from him—deserted him, if he consulted his gut. And fixing this mess was up to him.

To get his necessary moves past Dortland, whose agents could intercept and stifle a message from his communication system, just like that ship, he counted on one conduit, his opposite number in the Outsider government—the very man he should be most nervous about trusting…and the one whose physical lines were the most immune to that ship out there, and to Dortland. Everyone considered that Outsider communications flowed almost universally by tap, immune to anything but physical eavesdropping on the sender. But there were internal office nets, well shielded. And a few shielded outside lines, which Outsiders guarded jealously, absolutely licensed to protect themselves and their communications from that ship and from Dortland, by force of arms if need be.

On a station riddled with surveillance, Brazis had the physical lines he needed.

“Ms. Jewel.”

“Jewel.”

“Of course.” Outsider names. No Ms. He copied the computer file, Kekellen’s letter, and gave it to her. He wondered where the bugs in his office did reside. But the kind he had to fear now were the kind that could focus their pickup through several walls, the highly professional and elaborate kind that Dortland commanded. “It’s important the Chairman understands my official position. Extremely.”

“Yes, sir,” Jewel said, and took the item into her keeping, in a button-purse she wore at her waist, clearly understanding where that was supposed to go.

“I’m sending Ernst to walk you home. With thanks to Brazis for your help. I hope you’ll convey that, personally. Take care.”

“Yes, sir.” Jewel’s eyes flicked left and right, as if a threat might be evident in the walls, resident with the ages-sealed lizards—or she might be aware of electronics he couldn’t detect. She might be amped. The ability of some of these couriers was legend. “Thank you, sir. I will thank him for you.”