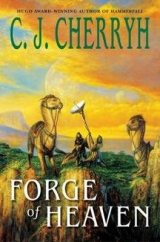

Текст книги "Forge of Heaven "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 25 (всего у книги 30 страниц)

12

WIND, WIND THAT HOWLED, tore at the canvas, wind that picked up wet sand and hurled it. Beshti hunkered down, moaning above the gusts. Marak hugged Hati to him, as canvas flattened against his back, poles bowing—it was well lapped under them, and driven down with deep-stakes into the rock, and it held, but his back turned cold, and the insistent headache throbbed with the howl of the gusts.

“Like one of the old storms,” Hati shouted against the racket.

“That it is,” he said, holding fast to his wife, trusting the beshti, sheltered, like them, behind a sandstone spire, would stay down until the gust-front passed. The wind stank of rot, chilled with antarctic cold—might wear through the canvas, it carried so much sand up from the pans. It rained up, at this edge of the cliffs. Water whipped up from the pans, upward on the gale. Thunder cracked and deafened them and the lightnings were a steady flickering light through the canvas.

It was not a time to try to see, or hear, or do anything but hold fast, breathe only through the weave of the aai’fad, venture no skin exposed, no more than they had to. Fabric would abrade, skin would gall, eyes would be blinded if they faced such a wind.

Like one of the old storms, it was, except this sand blast had an edge of melting sleet, except this presaged a lasting change in the world, no simple march of dunes, but upheaval of the climate itself.

He hugged Hati’s face against him, and they breathed in the hollow their shoulders made. His other hand clenched the rope that he had made fast about the spire itself, in the chance the wind should try to sweep them off the ledge, and well he had, he thought. Very well he had.

“ANTONIO.”

Brazis reached spasmodically for the desktop control and physically knocked the amp way down on the tap. It was Ian.

“Ian, what in hell’sgoing on down there?”

“An outlaw tap, the Ila confirms it. She denies all responsibility, and says look to those who want war in her name.”

“What’s she talking about?”

“Movement, apparently. Third Movement, on Concord.”

At least he was ahead of the game on one thing. “ ThirdMovement, is it? I already have a report to that effect on my desk, but I’d profoundly hoped not to hear that word from you.”

“The Ila expresses extreme indignation, insisting she has no relation to these persons, whoever they are.”

He’d believe thatwhen the sun burned blue. “I’m pursuing this illicit tap with all resources. Which are now very scant, Ian. Her blowing through here has put a significant number of taps on the sick list or in hospital. Some may not recover. Her own will not recover. This doesn’t fill me with great confidence about her intentions. Be careful.” He didn’t mention the ondat.

“We’ll take precautions.”

“What about Marak?”

“Marak is well out of this.”

“Is he safe?”

“Safe as a man can be with a sea rushing through the gap. Madder than hell about his tap being taken without his consent. That wasnot approved, Antonio.”

“I would have been pushing it, to explain the background of the situation without breaching security. I couldn’t gain his consent without explaining more than he wants to know.”

“Maybe you can convince him of that. I marginally suspect he knew the Ila was doing something illicit, and that’s why he took this crazy notion to ride out and watch the west coast slide into the sea. Maybe he wanted to get out of the Ila’s reach, but that’s nothing I can prove.”

Incredible theory. But one never said incredible, in Refuge history. “Can he have any concept of this Third Movement business?”

“He has his sources. At least for what touches us.”

Memnanan. The Ila’s longtime head of staff. Those two had passed warnings before. He’d bet on Memnanan having said something, if anyone.

“Are we going to have a feud between them, next?”

“He’s not angry at her. But annoyed. That’s how I’d describe it. Massively annoyed. When you live this long, Antonio, you have a strangely patient perspective on other immortals’ doomed enterprises. There’s very little you haven’t seen before. If he was in on it, he knew he could only make trouble for Memnanan by spoiling her venture out of hand.”

Not angry at her for provoking the governments aloft, yet mad about a personal inconvenience.

Or maybe about what he considered a security lapse and a threat to their safety. He had never thought of Marak as keeping secrets of that nature from his office.

Maybe he was just very good at keeping his secrets.

“A doomed enterprise, in the Ila’s case? Do you dismiss it with that?”

“I’m sure the Ila herself thought so from the beginning, but someone at your end decided to act in her name, and it was, yes, a diversion for her. I think so. I still think it’s minor and that she didn’t instigate it, only took advantage of it to see what would happen. If certain fools wanted to play out their game to your detriment, she certainly wouldn’t prevent them doing it.”

“I’ll accept we’re being spied on,” he said to Ian, “and I don’t know if you know more than you’re saying, or if you say what you’re saying now with her full knowledge…but I have an immediate need for facts up here, Ian. This is all going to hell on us. I do know of one unauthorized tap on station, sent here from Apex, who may be what she’s complaining of with this illicit-tap business, but I’m not betting that answers the whole question, not considering what we’re dealing with. Has anyone contacted youat all, that I don’t know about?”

“No.”

“Can you make it clear to the Ila in some reasonable way that trouble is proliferating up here, that people have died needlessly, and if she knows anything, or if she’s in contact with any illicit tap in our area, she should tell us and give us identities. This Third Movement group has taken her name as their cause, if what you suspect is true, Earth’s heard about it, and they’re trying to insinuate its own investigation onto the station. They’ve subverted the governor’s security, and the ondatmay be making some move, and if they haven’t yet, they’re likely to. Doesn’t anything in that set of facts catch her notice? It had damned well better, Ian, or I don’t know what comes next up here.”

“I’ll inform her of all that. And I’m trying to prevent another such outburst on the system. As you point out, Marak is likely going to throw the next hell-fit. He’s cold, it’s raining, he thought he had the beshti, but they took out to another terrace, just out of his reach, while he was incapacitated with that tap-spike, and his area is becoming more and more hazardous. He’s well out of patience.”

“I can’t help him. He’s put himself where we haven’t even got good overhead image and we can’t get through to him reliably. If we start trying to direct him up that maze and then lose contact, he could be worse off than he is. Best he uses his own instincts.”

“He wants the boy back, Antonio. If you could just do that, you could do a great deal toward getting communication calmed down all round.”

“I assure you I’m trying to get him back. Ask the Ila, while you’re at it. Is there something else she hasn’t told us? Has she been passing notes to this illicit tap source, or has she been fighting it? I’d estimate she hasn’t been fighting it, if the whole system hasn’t blown up. I need to know if that illicit tap is her doing.”

“I’ll try to get your answer. It all depends on the Ila’s goodwill, which may be extremely ruffled at the moment. In any case, I’ll be back as soon as I have any information.”

“Thanks, Ian.”

What else could he say? An honest answer depended on the Ila’s personal comfort and how far she thought she could annoy them. It depended on her idea of how much damage she could safely cause them and then back off untouched. He knew of incidents in the past, long before his lifetime, that had wreaked havoc on the powers of Concord, all thanks to her.

And what could they do with her if she’d violated quarantine? Isolate her? She was already isolated. They’d bet everything they held dear that she was isolated.

Now she’d found a way to evolve her tap and God knew what other nanotech into something they hadn’t detected until she did it with someone who wasn’t even on the planet. His technicians said the thing had hopped frequencies. They’d never seen the like.

And if she was passing notes to conspirators up here—

If there was a cell here, if she’d found her way into the common taps, or if a rogue tap in the Project had helped her—she could have communicated all sorts of technology elsewhere. Her frequency-hopping nanocele, this recent innovation, could be on Orb by now. It could be all the way to Earth.

WOBBLE AND WOBBLE. Procyon knew he didn’t hew a straight line down the street. He stopped and rubbed his eyes, trying to drive the lights out of them.

Buzz. Buzz.

And voices. “Brazisss,”one said, and he tried to answer it.

“Sir?”

“Procyon!” Not from the tap, from behind him. He turned awkwardly, caught his balance, seeing a haze of blue and gold, a presence that reached out and held his arms.

“Brother…”

It was Ardath, Ardath, in public, on the street. “I’ve got troubles,” he began to say. “No. Don’t be here.”

But Ardath had help, one dark, and one gold, who took him each by an arm and told him come along, now, no argument.

Direction, from someone who could see clearly, someone he knew was on his side.

“He’s fevered,” one said, the darkness. “You can feel the heat in him.”

“It’s a mod.” A female voice, the gold. “No question it’s a mod taking hold.”

Light flash. The terrible pain in his head made his eyes water as he tried to walk with them. He couldn’t coordinate an objection. He just breathed, and walked, and hoped they would get him home.

They went through a doorway, into shadow, a relief, at least for his eyes. He could smell alcohol, old beer, not his sister’s ordinary level of establishment. He heard synth-wood chairs moving on a synth-wood floor, voices that echoed around and around. It was Auntie Murphy’s, he thought. He knew the older, rougher bars up and down the street. It smelled like Auntie Murphy’s.

“Hush,” Ardath said, and a chair scraped. “Sit down. Sit down, brother, and catch your breath. Your mods are having a war with this thing. Help them settle. I’ll get you something to drink.”

He fell into the chair he hoped was under him, finding a welcome table under his elbows. He was so tired. Sickness and fever buzzed in his veins. Mods, they said. And he didn’t have mods this fierce. Not what the government had ever given him. Panic beat in his veins, riding his pulse.

Commotion around him diminished. He heard his sister’s voice somewhere, giving directions.

A scrape of a chair. “Stupid brother.” She was back. She shoved a cold baggette into his hand, and pulled out the straw, bringing it to his lips. “Drink it all down.” Her hand was on his back.

He drank it. The stuff didn’t taste that bad. Tasted of salt, which he wanted, needed terribly, chased by the complex tang of other minerals.

He grew dizzy. Put his head down on his folded arms. Didn’t know how long he sat there, trying to keep down what he’d swallowed.

A little improvement in the nausea. But the flashes in his skull multiplied, blinded him. The buzzing began to make words in his ears, flat-sounding words, like a synthesized voice.

“Marak,”it said, or he imagined it said. “Brazis.”Over and over again.

Then a different voice: “No question he’s alive, sir. Procyon Stafford is the most notorious face on Grozny right now.”

“Procyon! Can you hear? Answer me!”

Tap. Brazis.

“Yes, sir.” He sat up and tried. He tried desperately, and saw and heard nothing but static bursts.

“Procyon,” Ardath said, right at his ear, hand on his arm; and he blinked through the illusory lights and saw his sister’s face inches from his, the blue and the gold cleared back, now, to show the Arden-mask. “Procyon.” Cool, anxious fingers brushed across his forehead. “Who did this?” Anguish. “Who’d have dared do this to you?”

Did he know that answer? Did he know anything, at all? But he remembered what he’d seen in the mirror, that mark, that horrid mark. He’d looked to her for help, and saw by the look on her face he’d brought her more problems than she remotely knew what to do with. Or should deal with. “I fell down. I think I fell down the rabbit hole.” Child’s story. “But it’s not funny, Arden.”

“I know.” A brush of her cool fingers across his wounded forehead. “I know it’s not.”

“Somebody shot the ambassador. But I couldn’t. I didn’t do it. I didn’t do it.”

“Idiot,” she said. “I know that. But they’re looking for you all over.”

“Down the rabbit hole. Only not full of rabbits. Scary things. Like the old story. Jabberwocky.”

“What’s this mark?” She touched the wound on his forehead, which felt like a bad burn. “Who’s our enemy, Procyon? Who’s crazy enough to do this?”

“Bad mods.” It was all he could think of, the card that he’d been dealt in a quarrel he didn’t understand. And then did. “The Earther. Looking for illicits.” A sick feeling, his head aching with pressure and dizziness that seemed to center in that mark. “Found them, found them, haven’t I?”

“Algol,” Ardath said. “Damn him, damnhim.”

Algol was almost certainly in the middle of it. She was right in that. And if it was bad mods, if his body was trying to organize a defense, he was holding his own. Barely.

“There’re slinks out in force,” Spider said, a voice from the shadows of the room. “Station security’s grabbed a lot of Algol’s people. They got Capricorn.”

And Arden: “Whoever the slinks haven’t got, weget. Find Algol wherever he hides.”

“No.” It was a government quarrel. Not hers. It was an attack on the Project, nothing his sister could deal with. Procyon reached out and took hold of Arden’s hand. “No. It’s too dangerous.”

“That fool’s touched my brother,” Arden said. “He goes down.”

“No. Listen.” The stuff that she’d given him was the right thing, to supply the warring nanoceles trying to pull the chemicals they needed out of his bloodstream. Now the threat to his sister roused up his adrenaline, and he began to feel for two breaths as if he could think, as if, doing that, if he could just hold on to his focus, he might be able to function. “No, there’s more, Arden. There’s a lot more than that. Not street business. Not the Trend. You can’t settle Algol. He doesn’t care about us.”

“Trust me,” his sister said, his little sister, his naïve little sister, whose little wars were fought with cold looks and whispers and the turn of a shoulder.

“No, not with this!” He saw her turn away from him, and he seized her arm. “Listen to me. Listen,Arden: I work for the government.”

She laughed and patted his restraining hand. “Oh, brother, that’s old news.”

“Listen. There’s trouble you don’t want to know, I swear to you, you don’t want to know. The ambassador’s shot, there’s something going on with the government taps…”

“This ambassador person is alive, in hospital, sleeping off a not very major wound. He’s been exposed to Concord now, poor dear, so he has to stay, and he’s cursed all the doctors, but he’ll have to come around to our view of the universe, won’t he, or he’ll be very unhappy in his life.”

Her information was newer than his, clearly. It made her too confident. “Listen,” he pleaded with her. “Someone’s shot him. That’s the point, Ardath. Someone shot him. This is guns.”

“And we know who would bring guns, don’t we?”

“Algol’s holed up in the Michaelangelo,” Isis said, and others had gathered close, listening, a ring of shadows in the dim light of the bar.

“I’ve got to tell you.” He made up his mind to that, because she knew too much, and not enough. “I need to talk to you. You. I need to tell you things.”

“Back,”she said to those hovering about, moving them with a wave of her hand, until there was a clear space, and he had to go through with it. “So say, brother. What? What do I need to know?”

He took a breath, shaky, all over. “It’s notjust Earth. Marak’s in a fix out in the desert, the Ila’s breaking in on us, and these people, these people who shot the ambassador—we’re dealing with the Movement.”

Ardath’s flickering mask, gold and blue, actually retreated to her hairline and lost itself. “Honest truth?” Childish question.

“Hope to die,” he answered, childhood oath, making the old slight move across his heart. “I’m not lying. I’m a Project tap. I’ve got to get home, Ardath. I’ve got to call people to take care of this.”

“Well, if there’s Movement, we know who they are, don’t we?”

“Ardath, for God’s sake…”

“Your government slinks came looking for me, for me,brother. They wouldn’t say why. They didn’t say someone had done thatto you.”

“This.” He lifted a hand to the burn on his forehead. Flash of dark. Something moving. He didn’t want to see that. “This—no. Not them.” She started to turn away from him and he caught her hand, too hard. “Ardath, what I want you to do—what I want you to do is get word to Brazis. Tell Brazis. He’ll send someone. He’ll take care of Algol.”

“And I just drop my brother down another rabbit hole, where maybe he won’t come out the same, or come out, ever. No thanks.”

“I’m already not the same.”

“You listen to me,brother. I know where our problems are. I know who’d be crazy enough to have done that to you.”

“You don’t know! This.” He touched the welt on his forehead. “This—I was in a place. I was in a dark place. And it happened there. Ardath, I don’t give a damn about Algol. Help me get a message out. Let Brazis handle it.”

“No.” She wasn’t believing him. “Not to take you away where you may not come out. Not to come tramping through the Street, breaking up everything. You’ll see, brother. You’ll see what we can do about fools.”

“Ardath, no.”

“Movement? Entirely déclassé.”

“No,” he said, and got up onto his feet, or tried to. And the buzzes accelerated, like a tap trying to come into focus. Buzz. Buzz. Buzz. “Brazissss.”Click. Click. “Kekellen.”Hiss. Crackle.

Brazis.

Kekellen.

A dark gold mask, a purse-mouthed face in the dim light, with the smell of ammonia. Oblong lenses glinted silver, hiding the eyes. Cleaner-bots, all around him, the station’s fearsome secret.

And he was aware of something else of a sudden. Of a wild presence…a dangerous presence in his head.

Hiss. “Braziss.”

“What is this?”Angrily. The Ila’s voice. “Who is this?”

Spike. Procyon felt it coming, convulsed, tangled with the chair and fell back into it, his head near exploding.

“Procyon!” he heard his sister say. “Procyon! Hold on!”

“SIR. SIR!” Ernst broke protocols, broke through the door, pale-faced. “Eberly, at the hospital. The ambassador’s having a seizure.”

Reaux sat at his desk, stunned.

“They say, sir, they say he could die.”

“SIR.” Dianne sent Brazis a physical call. “Technical’s on.”

“Who am I talking to?”

“Hannah Trent,” the contact said. Head of Systems. “We’ve been hacked, sir, major hack. We’re on it. We’ll get it back. The hack is mutating on us, hopping left and right, not from the uplink. It’s coming from somewhere near 10th and Blunt. Shall we send out the emergency vehicles, show of force? We need to find the source.”

“Do it,” he said.

Their intruder had hit the system.

Stop the Ila from her provocations? Impossible.

Ian take preemptive action against another of their small fraternity? Never yet.

Marak. Never forget Marak, or Hati, or Memnanan—you rule the heavens, they’d say. We rule the earth. Don’t read us lessons. Don’tgive us orders. Don’tbring us your troubles.

Brazis raked his fingers through his hair, wondering if he dared leave the office and go out himself—wondering if he should rely on Magdallen or if he suspected Magdallen of a consummate double cross, maybe even beingthe problem he was hunting.

Magdallen had been ill in the office in the prior incident, as powerfully affected as the rest of them when the Ila came blasting through the system.

Dammit.

“Dianne.” He started to ask her questions by tap, as he did a thousand times a day. And stopped himself from what had become a life and death risk. He hurled himself to his feet and went to the door. “Dianne.”

Dianne was tight-lipped, alarmed. “Sir?”

“Relay to Langford. Shut the taps down. Shut it all down, common and private. Turn all the relays off. Now, before we have more dead!”

“Contact with the planet, sir—”

“Shut it all down! Now!”

The relays had neverbeen shut down from the station, not for two seconds, in all Concord’s several existences.

But it would protect the taps they had left.

It meant that Ian and Luz were on their own, except the local planetary net.

If they, in reaction, shut thatdown, then everybody was on his own.

“BROTHER,” PROCYON HEARD, felt the table under his face, felt the close physical press around him, a hand holding his against the surface. He tightened his fingers, gripped that hand, got a breath.

“I’m all right.” Deeper breath.

“Get those damned things out of here.” Ardath’s voice. With fear. That wasn’t accustomed.

“How?” someone asked.

Procyon lifted head and shoulders, freed his hand and propped himself on his elbows. Ardath was there, with Isis and Spider and a couple of others whose names he didn’t know. He wiped his face, hearing a nightmare click-click-click, and looked down, beside the table.

Two bots, two little lumps of metal and plastics, with winking lights, sat right at his feet.

“Braziss,”whispered the new voice in his head.

“Yeah,” he said to it, just him and it, alone, in an inner nightmare. “Yeah, I hear you.”

“Procyon?” Ardath leaned into his frame of vision, attracted his attention with a touch on his hand. She was sitting in the chair across the table. “You stay here.”

“You’re not leaving.”

“I’m not waiting for you to die. Or be swept up into some government hospital. I’m not having it.”

“You don’t remotely know what you’re getting into.” Brazisss,the inner voice said. And: Marak. Marak.

“And youknow?”

And what good was he? What good was he, with whatever had gone wrong with him?

Marak,the inner voice said, but he couldn’t reach Marak. He was branded with the ondatkeepaway. People were scared of the sight of him, that was what good he was.

That was something.

“I think this thing is real,” he said to her. “I think this mark is real. There’s a war going on. And I’m in the middle of it.”

“You stay here. We’ll fix Algol, we’ll settle with him, and then we’ll talk to Brazis, if he wants you back. We’ll negotiate.”

Brazis wouldn’t give a damn for his personal wants.

Marak might. Marakwould want his own information. Somewhere between Brazis, the Ila, and Marak, there would be hell to pay.

But if the mark was real, if that dark place was real, there was something else. Something with its hand on him. Its voice buzzing in his head.

Something with an interest in him. Keepaway. Keepaway. Set aside. Claimed.

Maybe he was still dizzy. Maybe he wasn’t thinking clearly. But there wassomething going on in the understructure of the Trend, the shadowy places that fed the Trend with illicits and legitimates alike. The Ila, Gide, Marak, and now him, him,become an intruder in his own circles—it was Ardath’s whole fragile world about to come under scrutiny because of him. And she wouldbe involved. She was in that elite class that rested, like a thin, fragile skin, on the questionable things that, all of a sudden, would be the object of conflict and furor around, of all people who had never intended it, her brother.

But if the Trend could purge itself, if he could keep her and him from being killed, there there was a chance Marak himself, given information, could find him. Could negotiate with the ondat,who regarded Marak, Brazis said, as the only honest human, the only one. He had his little robots, his link with that dark place. They blinked and buzzed beside him. They found him, where he went. He had that straight, now.

Where he was, very powerful entities had ears and eyes.

“If you’re going, I’m going,” he said, trying for steadiness in his voice. “If you’re going onto the street, little sister, so am I.”

WATERFALLS POURED OFF the heights, and the beshti, on their feet now, in the passing of the gust-front, bawled protests about the weather—justified protests, with the racket of thunder. Marak held on to the tarp from one side, Hati from the other, and they kept the worst of the storm off, warming each other, but the beshti remained on their own, outside, in the lightning-lit downpour. Whether the cliffs above them or under them were stable—that was beyond any precaution they could take, but to stay clear of overhangs.

The momentary confusion in the heavens of Brazis’s domain seemed to have settled. That moment when they all, all, from the least to the highest, could hear each other—that was unique in Marak’s experience, and not something he wanted to experience again.

But it had passed as quickly as the front itself, leaving the thunder, the storm, and solitude—a sense of quiet for the first time since he was very young indeed.

He hoped the boys up on the ridge had paid attention to the deep-stakes. The gust-front that had run ahead of this storm, particularly up on the exposed ridge, was a test of their skill. There was a knack to tuning the tent to the wind that gave it stability in weather. It had never been this sorely tested. He hoped the boys had learned what he had taught them.

Equally, he worried about his youngest watcher, who he feared was isolated now in a different kind of storm in the heavens, and who had to fend for himself in the mess up there. He had made his opinions known to Brazis. But in this silence even from Ian, now, his watchers had to watch out for each other. He could no longer reciprocate the favor.

He sat snug against his wife and listened to the beshti. Somewhere near them, loose rock gave way and crashed down the slopes.

“I almost had him,” he said to Hati, thinking still of Procyon, and that moment that everything had crashed open. “I almost had him. Then it seemed I heard another voice. It made no sense at all. If I tried, I might still reach Ian. That way seems open, still.”

“Leave Ian to sort it out,” Hati said, hugging his chilled limbs. “Clearly the boy is alive. Folly to move in this downpour. We might at least get some sleep, husband.”

Hati was never one to batter herself against the impossible. She snuggled close, and he shifted to increase the warmth.

He heard the other beshti complaining in the distance below their perch, a trick of the wind, an echo, it might be.

“Marak.”

Clear and cold. The very man he wanted to hear. “Ian. What happened? What is the sudden racket and silence up there?”

“We have no idea.”

“We have every idea,”the Ila’s voice interposed over Ian’s. “We have a perfectly adequate understanding of what happened up there. The fool director has completely cut us off.”

“Ila,”Luz interjected.

He had been worried because the tap had been silent. Now he had no patience for this bickering. The width of the desert was not enough to insulate him and his wife from the Refuge and its petty politics. “All of you,” he said sharply. His arm had gone to sleep under Hati’s shoulder, and tingled as she stirred. “Settle your differences. I have no interest in all of this, except the safety of my watchers, two of whom are dangerously affected, if not dead, and one of whom is pursued by Brazis’s enemies and now held from talking. Break the system open. Tell Brazis stop this nonsense, use his resources and pull Procyon back to safety. Now.”

“That is the very point, Marak-omi,”Luz said, “that the station wants no contact with us at the moment. Brazis apparently detected a Movement cell active on the station. We believe Brazis is the one who shut the link down, for defensive reasons.”

“We are far from certain,”Ian said.

“Folly,” Hati said disgustedly. She had sat on the periphery of this conversation. But she clearly heard what Ian and Luz said, all on her own. “My husband says it all. We are wet, we are cold, we are at this moment in very ill humor on a cliff that may pitch us down into the basin, and when we get off it, trust my husband will not rest until Brazis accounts for this boy. Ila, we appeal to you.Tell us the truth behind all of this.”

“About fools who call themselves Movement? Who engage in illicit trade and infiltrate new technology into the system? I know nothing at all substantive.”

“We have our deep suspicions,”Ian said.

“Enough!” Marak said, beyond angry at this sniping and bickering and insinuation. “Isit Brazis who shut us off, or is there some other agency?”

A crack of thunder. A gust of wind carried rain under their shelter, threatening to tear the canvas away from the three irons they had embedded.

“We have not the least idea,”the Ila said carelessly. Marak could see the gesture in his imagination, a lift and wave of the fingers, dismissing his strong hint of other interference—or some enemy diverting their attention elsewhere.

“Hati,”Luz said, “Marak-omi, we need you. We need you both. We ask you stay with us.”

Oh, doubtless Luz needed their support in the situation now, Marak thought. Doubtless Luz now repented her bickering with Ian and even more bitterly repented her period of friendship with the Ila. Doubtless Ian and Luz alike dreaded being deserted to the Ila’s society without his mediation. Half a year was already wearing on their close, three-sided society…without him in the Refuge. They were ready to call him back. And if his and Hati’s absence had driven Ian to the far end of the Paradise and actually precipitated this event, he regretted it, but he much doubted that was the case.

Dared he raise the thorny matter of Brazis’s personal faults with Ian now? They all had ears to hear. They all would have heard what he had heard in the system, if they had been listening at all. The three of them at the Refuge had all known, if he had not imagined it entirely, that there was something seriously wrong on the system. They had failed to raise the issue or warn him. Subtlety and subterfuge was at work, and he had no desire to fling sand in the soup before he knew what the new alliances were.

“We have no choice but tend to our own affairs, our way,” Marak said. “We expect others to do what they can.”