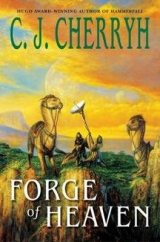

Текст книги "Forge of Heaven "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 30 страниц)

“This isn’t a situation you asked for by word or behavior. It’s political, and I’m relatively sure it’s Earth pressing for some advantage, and using any anomaly they can find to justify whatever they’re after. It’s far from certain you’re in any sense the real center of this inquiry. You’re going to have to use all your wits on this one.”

“Yes, sir.” God. How had he gotten involved in this? Why him? And he desperately wanted a briefing on the downworld situation. “Quick question, though, sir. I’m not going to relax this evening. Would it remotely be possible for me and Drusus to switch shifts? Or at least let me have the current transcript. I don’t want to raise questions with Marak that I can’t—”

“Use your wits, I say, or a missed session could be the least of your worries. Concentrate on the business at hand. I applaud your devotion to duty, but Ian knows exactly where Marak is. The new relay’s working. We’re in reliable touch with him and with his camp. Ian says the camp is geologically sound despite the shaking. Drusus has explained your absence to Marak. You’re covered down there. Concentrate absolutely on what you have to do in this interview. If you make a mistake of any kind with this man, let me make it clear to you, you’ll hear from the High Council, the Chairman General, and from me, personally. Do you understand that?”

“Yes, sir.” Soberly. Heart pounding harder. “I do. I’m frankly scared.”

“Understandable. Are you at all flattered this Mr. Gide came here asking for you?”

“No, sir. I’d rather he hadn’t. I’ve thought and thought. I can’t imagine a reason.”

“Don’t be overawed by his attention. The man is a diplomat. He may be exceedingly gracious. Don’t go off your guard. I’m sure he can threaten. Don’t be spooked.”

“Yes, sir.”

“I wouldn’t send you into this if I didn’t have confidence in you. You want to know why I agreed to this.”

“I do wonder that, sir.”

“Consider. He’s here at extravagant difficulty, making an extravagantly provocative request, which he knows I could say no to, absolutely. Probably I should refuse him, and I think Reaux expected me to. But he failed to get an issue on that. And we know one thing: we’re not talking about a fool arriving here on a personal whim. This will be a very clever man with an agenda we don’t know. He comes with Earth-based credentials, not just Inner Worlds, intruding into Project business, which means he and whatever he represents have stuck his neck way, way out. Earth has very many institutions. We don’t know which one this Gide actually represents, and we may never know. But if there’s a clue to be had as to which faction is sticking its nose into our affairs, I want to know it. It could be someone looking for an issue to raise back at Earth, to reinforce their politics. It could be a legitimate anxious inquiry into your background, which we both admit has a shadow on it.”

“Yes, sir.” He was beginning to have fears that ran under doors he couldn’t possibly open.

“Expect state-of-the-art truthers, which I can guarantee were running all the time you were talking to Reaux. Are you in fact up to this, or do you need to have an attack of something contagious?”

“I’ll do my best, sir.” I don’t knowdidn’t get you points in the Project. I can’tmight lose them.

“Observe, don’t interpret, just as you do on the job. You don’t want to know too much about this. Deeper knowledge could very easily bar you from places you want to go in your life. Let me play politics. That’s my job. Yours is to go on being innocent, and in that innocence, to protect the Project from an inquiry Earth isn’t allowed to make. A further piece of information. You’ll continue to be shut off Marak’s tap for the duration, for security reasons, not because we don’t trust your integrity, but because we don’t want them probing it.”

He was appalled. “Can they possibly dothat?”

“The signal’s within the electromagnetic spectrum, and they can certainly try it. If it happens, don’t cooperate and get out of there fast. You know the rules. I don’t want to frighten you further, but if they physically grab you, don’t cooperate, and leave if you can, with whatever force you need. If worse comes to worst, trust absolutely that we’ll get you out. I’ll contact Marak if I have to. It’s one reason I dare send you in there. I have no doubt we’ll get you back safely. Just don’t make me have to do that.”

“Yes, sir.”

Brazis tapped out. Gone.

My God, Procyon thought. He felt sick at his stomach. He didn’t know why this business had arrived in his lap, except his teenaged stupidity in getting into a questionable group, in listening to ideas different from what he’d heard before—it was his only real sin in his whole life, politically speaking, in any sense that would ever reach to Earth’s files. One mistake, and it came back to haunt him. He wished this business were all over with, and for the rest of his life after, he swore he wanted to live as far away from Earthers’ notice as he could get.

We’ll get you back safely, kept ringing in his ears. And, Mr. Jones,for God’s sake.

What did Brazis think he was going into?

MAGDALLEN HAD SHOWN UP—on time for his appointment, give or take five minutes, but Brazis was in a touchy mood at the moment, touchy enough to keep an Apex agent waiting in his outer office. Several reports had flashed across his desk in the last while, most notably Marak’s irritated reaction to Procyon’s continued absence.

Worse, Marak, having followed the trail of the runaways to the brink of the ridge, was now well down on eroded terraces and sand slides, stubbornly proceeding where, Drusus informed him, underlying sandstone could crumble without warning. Marak had a few notorious flash points: deception in his contacts, mechanical devices in general, and Ian second-guessing his firm decisions at the head of the list. Left to his own devices, Marak might have given up the pursuit and come up again to take other measures; but then Ian,who had his own flash points, had gotten hot about Marak’s decision to go down off the ridge, Drusus had seen fit to relay that to Marak, Marak had gotten hot in return, refused Ian’s help, saying he had the beshti in sight, and now it was clear that hell would freeze over before Marak gave up and retreated.

It was already a delicate business, keeping what happened on Concord away from Marak’s lively and very experienced interest, while pursuing an investigation about Earth’s poking about in matters it should never touch—that was one thing. But Drusus, damn him, had straightaway committed them to a particular line of explanation that involved Earth—admittedly within the allowable degree of latitude, but letting Marak know that Earth was an issue in Procyon’s case. And if Marak did find out what was going on up here, he’d find it out while he was already feuding with Ian, again thanks to Drusus’s decisions.

The juxtaposition of issues was like fire near explosives. The very last thing any of them wanted now was Marak, already in a temper, conveying to the Ila, whose relations with Earth were ancient, unpleasant, and always full of acrimony, that Earth was now interfering with their taps, potentially including hers.

Thatwould fry the interface. Absolute disaster. He wanted to strangle Drusus, who hadn’t been aware how dicey things were.

Ian and Luz, meanwhile, already quarreling with Marak over methodology, were monitoring the aftermath of a second very strong quake to the south. Everything Marak had come south to observe was now in full career, a spectacle that had the geologists glued to their posts in anticipation. Over a matter of hours two high salt waterfalls had sprung out on the inward face of the Southern Wall, white threads presaging a far greater flood. Icy polar water was tearing itself a wider access to the hot southern pans of the inhabited continent. Marak had lost his bet with fate—source of half Marak’s temper, Brazis had no doubt. Ian had proven right: they should have used the rocket in the first place, and now Ian rushed to get a backup relay soft-landed on the Wall itself, a tricky bit of targeting, while the landscape out there was changing by the hour.

The northern end of the basin itself might have dropped another half meter relative to the Southern Wall in the last strong aftershock, which had the geologists on station scrambling to revise their predictions both of the extent and speed of the event, and of the consequences to anybody in that region, notably Marak and his stranded party. A major inland sea was arriving in what had long been mountain-shadow desert, deepening over an unknown amount of time, depending on how much that sand soaked up, for starters. The mountains in the northern part of the basin were predicted to become islands. The frozen southern sea, a weathermaker for the southern hemisphere, was in the process of acquiring a shallow, sun-heated annex, which, the meteorologists said, was going to mean fog. Mist. Rotten visibility, that was already obscuring the site of the break in the Wall.

And as for Marak, the need to reassess his party’s situation and cope with the aftershocks mightdistract him from asking more closely about Procyon for the next couple of days; but it wasn’t going to improve Marak’s mood or the ease of dealing with him.

Meanwhile hehad the inquisitive ambassador andFrancisco Magdallen to deal with. An Apex Council agent poking about in the usual habitats of trouble was a common enough nuisance throughout the territories, just the Council keeping tabs on Concord Station to confirm what the Chairman of Concord and the director of the Project patiently and correctly told the CG was the truth.

And to top things off they had the arrival of this Andreas Gide, who wanted Marak’s tap for a face-to-face interview. So to speak. Did he now believe that Magdallen’s presence was coincidence?

Trouble didn’t just come in threes: it gathered passengers as it went, and crashed nastily into bystanders.

He deliberately calmed himself. Had a few sips of caff, which had cooled enough by now not to scald his mouth.

He tapped in, a simple contact with his aide, Dianne, outside. Dianne escorted Magdallen into the office.

The man had clearly responded in respectful haste. The gray coat mostly covered a shirt that belonged on Blunt, the shoulder-length curls were done up in a clip without benefit of a comb, and the eyes, brown at their first meeting, were outrageous green, a green purchasable in cheap shops. Brazis didn’t take it for granted those particular lenses were cheap, or without augmentations, or that they were locally-bought lenses, at all. He proved it by a fast tap at a button on his desk.

Clean, however. No transmissions.

“Mr. Chairman.”

“Agent Magdallen. Have a seat.” Brazis waited, and poised himself comfortably backward behind his desk, arms on his middle. “So what’s your news this cheery day? I would expect there’s news for me, with all this going on.”

“Gide is on the station in an unfamiliar containment vessel. I don’t know its capabilities, but the bizarre impression it creates where he travels is surely part of his intentions. To intrigue us. To intimidate. To make maximum stir here on the outer edges of human civilization.”

“And among the ondat,a demonstration of technological wonder.”

“Forever the ondat,yes, sir. But one doubts they’re awed.”

“Gide has asked to see one of Marak’s taps. The youngest. Procyon.”

“Procyon.” Magdallen frowned. By his look, he actually hadn’t known about Gide’s summons of the young man, which argued that his major sources tended to be in the environment where that shirt was ordinary.

And one could then hope that Reaux’s office didn’t, at least, leak information too quickly to the Outsider streets, no matter where else it might go, among Earthers.

“Did this Gide give a reason for this request?” Magdallen asked.

“A whim, he would have us think. A five-hundred-light-year whim brought him here to ask for an interview with a, for all practical purposes, junior tap.”

“Perhaps Earth doesn’t like such a young man in the office he holds,” Magdallen said. The man had an annoying habit of not quite looking up when he spoke. “Or perhaps Earth doesn’t like what they hear of thisyoung man. Who does have unusual contacts present and past, of which I’m sure you’re aware. He has crossed my area of inquiry.”

“ Whatarea of inquiry?”

“Into the Freethinkers. What did Governor Reaux have to say?”

Was he querying the agent, or the agent querying him? Magdallen was quick to provide an excuse for knowing about Procyon’s past.

“What contacts?” he asked Magdallen sharply. “What contacts does Procyon have that possibly concern your investigation?”

“His sister, whose contacts are numerous, some low, some high. I looked him up, sir, for the Freethinker connection into high places. He is an anomaly.”

“He can’t avoid being that.” Brazis considered the question Magdallen had posed to him, considered the source and the set of motives, none of which he quite trusted in this man who didn’t work for him. Tell him? Encourage confidences? Or slips? “As for Governor Reaux, who just had an interview with young Procyon, we talked. We shared nothing but the basic information. We’re left to assume Gide is putting his nose into Outsider affairs—and through Procyon, possibly into planetary affairs, more critical still. If not into this Freethinker interest of yours.”

“That is a question.”

“Can you answer it?”

“No, sir, not yet.”

“I don’t take such an intrusion into our affairs matter-of-factly. But yes. What about this Freethinker connection?”

“I have numerous inquiries going on. None that bear fruit. May I observe, sir,—you had to consent to this interview.”

Brazis rocked his chair slightly, irritated by the stone wall, increasingly not liking that diversion—or the implication of fault. “Yes. I did.”

“Clearly you have a reason.”

“Curiosity.” Deliberate cold answer to the authority this agent represented. And to any report he might be drafting. “Tell me, Agent Magdallen, what is Earth doing here? Who is Andreas Gide, and does he represent anything legitimate or changing, back on Earth? Unless you have some direct information on that score, which would surprise me and gratify my curiosity, and make me change my mind in a heartbeat, yes, the interview is granted. What in hell do Freethinkers have to do with it all?”

“I don’t know that they do. If I knew anything at this point, I assure you I’d say it, to prevent this. I’m very uneasy about your consent to this meeting.”

Magdallenwas uneasy, as if Magdallenhad an opinion of his own that overrode his authority. Forget the Council, if he’d ever suspected it. Magdallen wasn’t a Council spy. This was one of the CG’s personal agents, one trying to find something very specific. Hell, yes,it was political. “Procyon is a trained observer with a good memory. An extraordinary memory. I will expect your support in protecting him, Agent Magdallen.”

“I’ve said I wouldn’t have recommended your agreement. I can’t promise…”

I, I,and I.Deeper and deeper. And this wasn’t a fool: Magdallen surely saw what the other side of the desk could read into it, the implication of a real authority backing him, on Apex. He meantto convey that impression.

“Frankly, Agent Magdallen, I can’t see letting Gide leave this station without knowing what he represents and what he’s going to report, and I can’t see letting him draw more extravagant conclusions from what he wasn’t allowed to see, to fester at distance. I say again, if you have more information on the precise reason he’s here, if it has any connection to anything you know, my decision can be modified. The young man can break a leg. Develop acute heat rash. But talk fast, or stand back and keep quiet, and don’t tell the CG that Iwas the stubborn one, holding back information that could have bearing, because I’m recording this session, and I’m not hesitant to bring it and you and himbefore the Council.”

“I don’t have more information,” Magdallen said. “Clearly what Gide represents has force, transport, and finance at its disposal. That’s allI can say.”

Confront the man? Demand under threat of arrest to know what he was and what he was investigating?

He wasn’t ready for that. This day’s disaster had gathered passengers enough. “It’s all I can judge by, either, and I take decisions as I can, with what information I have. Earth is Earth. It organizes itself, and then it fragments and shoots its own citizens for centuries on end. One last appeal to reason. Does this request of Gide’s possibly, remotely agree with anything untoward that you know, Agent Magdallen? Any scrap of a scrap of a rumor down on Blunt or even far off in Council halls on Apex that you really ought to tell me at this point?”

“I’m not convinced this arrival does involve Blunt—at this moment. About the other I’m not in a position to say.”

Damn him. Damn him.

“So we have Gide. And the visible anomaly in Procyon is, as you say, his youth and his former affiliation…down on Blunt Street. Tell me, Agent Magdallen, might you yourselfbe an item of their interest?”

“I would very much doubt it, sir.”

“Is smuggling illicits actually your concern down there? Or the Council’s? Or do I draw conclusions that Council might somehow have foreseen this ambassador’s arrival and sent you here? Might I hazard the remotest guess that your business here was alwaysthe chance something like Mr. Gide might show up?”

A moment of hesitation. Magdallen looked at his own hands. “I will confess that Mr. Gide has suddenly become a concern to me, sir. What motivates his interest, and who sent him, I do intend to learn if I can, since I’m here. I report to the Chairman General personally. I’m sure you know that by now. I’m sure if there are issues surfacing on Earth that we haven’t picked up—I’d be very glad to pick them up, if I can, and I’m sure the CG would be grateful if I can. These I would report to you, if I knew them, but no, that isn’t my mission here.”

“Don’t stir the broth, Agent Magdallen. Get your information on Gide directly from me and tell me what you hear from other sources. This business is delicate enough without your personal intervention to complicate my life. Let’s minimize the number of vectors in this mess.”

Eclipse of the remarkably green gaze, a downward glance. And glance up. “I’m a model of discretion. No one in my line of work ever wants to create issues, I assure you, Mr. Chairman. My job is simply to report them where I’m scheduled to report.”

There. He’d thrown out a rational appeal for cooperation and Magdallen’s answer was a standoff. He restrained his temper. “I’ll share information with you as it becomes clear. Stay out of the collection business in Gide’s vicinity.” Conversation with Magdallen had to be bounded by prudence—defense of the Project’s prerogatives as independent from Apex governance, even while the general conduct of civil and international affairs he handled as Chairman wasanswerable to the Council at Apex.

He was increasingly uneasy in his dual role. Second-guessing said he might have made a mistake in his decision to allow Procyon to take the chance, that he ought to have hammered Magdallen for information before he ever agreed to send the boy into either interview, little as he’d gotten from the Council ferret before now or in this interview.

And still—still he hadn’t learned anything he hadn’t expected from Magdallen. He hadn’t yet had Magdallen’s complete cooperation, and he still very much wanted the benefit of knowing what Gide was after…which might well be what Magdallen himself was after.

Sitting back, letting Earth affairs develop without learning what was going on—Apex wouldn’t thank him or respect his authority for letting events slide on their own. Politically immune he might be, at least as director, but revolutions on Earth and in the territories involved untidier and more dangerous situations than orderly elections and quiet political cabals: assassinations had happened, covert removals had happened. Untidy political actions notoriously annoyed the ondat,who were always an issue. He didn’t intend to be removed—for the good of the Project and the health of humanity he didn’t intend to be removed.

Others, then, might have to be.

“I appreciate your full cooperation, Agent Magdallen.” He rose and held out his hand, ancient gesture, deliberate and provocative gesture in a world of potential contaminants and infection. “Your cooperation and your reports, as you’ll choose to give them to me. I know you’re not legally bound to report to me, but I shall very much appreciate your opinions and your advice. And your alert observance on the street. I expect to have it, under present circumstances.”

“I appreciate the warning, sir,” Magdallen said, shook his hand, and immediately left—taking himself and that extravagant shirt back, the report of his own agents would suggest, to a certain apartment on Blunt—to leave the coat in yet another apartment he maintained in a very seedy neighborhood on 2nd Street.

It wasn’t to say he didn’t wipe down his hand thoroughly after Magdallen left, and he was confident Magdallen would hasten to do the same, probably going straight to a washroom. It remained a visceral comfort, the lemon-scented wipe washing off the memory of a foreign, off-station contact, not that he truly dreaded foreign contamination from Apex. The new scent, primeval cure, canceled the lingering presence that could convey viral intrusion or—in this hotbed of politics that Concord always was—things far more elaborate and damaging.

Being remote cousins of Earth, even knowing there were remediations, Outsiders had never quite cured themselves of fear. They didn’t go so far as to use robot interface. Outsiders trafficked with other worlds, observing sheer bravado in their personal contacts—but still, for psychological reasons, scrubbed such contacts off, frequently kept packets of wipes or Sterilites in their pockets, quite, quite silly as the action was. If Magdallen had brought any engineered contagion aboard, the whole station was already at risk. Always was. Always had been. Always would be. Far more threat than a sensible, well-paid agent from the central authority, the station had its biocriminals and its active nethermonde, that element that had threatened, and acted, usually for petty profit, sometimes for political reasons, on numerous occasions that the Office of Biological Security had had to scramble into action.

As for their ambassador from Earth—forget any trivial threat of germs from them. Earth wasn’t a threat: they feared biotech too much. Hence the containment unit.

One always, always, worried about one’s internal security, however, when the likes of Magdallen showed up, as Magdallen had, two years ago, about the time Procyon had risen to his rank, about twice the time ago this ship from Earth would have launched. Or a complete cycle, if something had reached Earth and bounced back to them, in the form of Mr. Gide.

Right now he was more than worried: he and Magdallen had bumped spheres of authority, and the air still crackled with the static.

Handle this. Handle it well, they’d challenged each other.

Neither he nor Magdallen could afford a mistake in the next several days, and now they both knew it.

THE LAND GAVE ANOTHER SHIVER, sending little stones and slips of sand down the long face of the terraces, warning that massive slabs of Plateau Sandstone that had sat for millennia overhead might grow uneasy in their beds. Marak cast an anxious look up, as sand slid down to cross their intended path.

Wandering terraces a mile above the pans, the fugitives had stayed out of sight, now, behind the spires of rock. They might have delayed, eating the new growth that still grew atop old sand-slips, but a relentless series of tremors had spooked them onward, down and down toward the bitter water pans.

Water itself was not an attraction. A beshta carried water in its blood, and, well watered a few days ago, they were not that thirsty. But, free now of riders and burdens, they followed ancient instincts for reasons that no longer quite applied to their survival. And they would, being beshti, go down, and down, and likely easterly across the pans, heading toward their home range, the young bull increasingly anxious to keep his females well separate from Marak’s old one, and maybe smelling him on the fitful wind. He was taking skittishness to the extreme.

“They made it down that slope,” Marak said to Hati, seeing the evidence of unstable sand, where beshti had clearly fallen and wallowed getting up. “I distrust that slope. Let us go a little over.”

Warmer wind whipped at them, swept up from the depths of the pans. A gust caught the tail of Hati’s scarf and blew it straight up. It had been like that by turns, but this southerly wind brought, rather than sand, a clearing of the air, and the scent of growing things.

They turned about, which, with beshti in a narrow place, was best done slowly, letting the beshti fully voice their complaints and test the rein. A new shiver of the earth underfoot gave them no help in the matter.

“Marak,”Drusus said. “Are you hearing me?”

“I hear,” he muttered, fully occupied at the moment.

“We can confirm the Southern Wall has actually cracked, omi. The cold sea is pouring into the basin. Meteorology thinks your weather will change soon. The earliest flood will soak into the sand and much of it will evaporate and meet cold air aloft. Fog is certain. So is rain. A great deal of rain.”

“When?” Marak asked, overlooking the distance-hazed pans, and a drop off a sandstone ledge scarcely a handspan from his beshta’s broad feet.

“They think the wind will shift, coming at first from the southwest, and meeting a front coming down off the Plateau—a great deal of evaporation as the seawater warms on the pans. There will be limited visibility, wind, and torrential rain, omi. We are watching that situation carefully. We are in contact with your camp. We have advised them to take extreme precautions. We urge you consider the possibility of thick fog and very poor visibility in planning your emergency route back. Above all, you should not go down onto the pans.”

As the beshti completed their precarious turn.

“We are not on the pans,” he said irritably, and to Hati, “The Southern Wall has indeed broken. The sea is coming in.”

Hati frowned, vexed at their situation. “So let us find these silly beshti before they drown.”

“Drusus forecasts rain and fog,” he said. “As well as flood.”

“Then the beshti may come up on their own,” she said. Beshti from the Refuge had learned good sense about flood, if not about inconvenience to their riders. They had no particular liking for being cold, wet, and unfed, and he agreed: if cold rain came before the fog, the situation could work to their advantage.

“What does it look like?” Marak asked Drusus, aching with curiosity for the sight they had hoped to see themselves, from a safe distance, to be sure. “What can you see at Halfmoon?”

“The two thin waterfalls,”Drusus said. “Proceeding from the cliffs. Clearly seawater has won a passage of sorts through formerly solid rock. We can’t see the source, which seems about midway up the escarpment, but clearly a crack has opened between the sea and the southern basin. As a direct result of the waterfalls, cloud is forming that blocks our clearest view from the heavens. We’re having to go to other instruments, so our view is adequate, but not as good as we could wish. We believe the gap will rip much wider very quickly. The rock there may be the same basalt as that in the ridge. If it is, we fear it will not hold long against the rush of water. And if that happens faster than we think, weather calculations will change. I cannot say strongly enough, omi, all calculations may change without warning.”

Without warning. The chance of their being at the right place to see this wonder in person had, over all, been very small, unless they had been willing to camp at Halfmoon for a few centuries and wait for moving plates to move and geology to have its way. Ian had argued it would be later, rather than sooner.

Other decisions—his, among them, a feeling that the frequency of small quakes presaged something—had put them on this slope. And by Drusus’s report, they were all running short on luck. The pans below them now looked entirely ominous, and fog and torrential rain was not good news. The descent after the fugitives was a maze, difficult to navigate among the spires, and the slots in the terraces hanging above their heads and the spires around them had not gotten there by dryland erosion. Rain pouring onto the bare surfaces up there would quickly find the best channels down. Streams of water would come off those cliffs in their own miniature waterfalls. He was bitterly frustrated to be in this predicament.

But frustration meant that they were alive, and still had choices, no matter they had missed the breaking of the Wall, which did not look to be a long process after all.

In his long experience, survival was always preferable to a good view of events.

NO ACCESS TO THE TAP, no contact, no information, nothing to do but sit on his hands and avoid contact with everyone he reasonably wanted to have contact with. At very least, Procyon thought, they could have rushed him off immediately to this meeting with the all-important Mr. Gide and been done with it, but he supposed Mr. Gide wanted to rest.

So he had to avoid contact with his ordinary associates, stay out of his ordinary comfort places, all the while having indigestion from sheer fright…and sit and wait until tomorrow, until Mr. Gide was in the mood.

So he poured himself an uninspired fruit drink, settled down in front of his extravagantly expensive entertainment unit and scanned fourteen channels of Earther-managed news for information that very obviously wasn’t going to be there, not in any degree of detail he wanted.

It was hell, he decided, being at the epicenter of information that the news itself didn’t know—you couldn’t learn a thing beyond what you knew, and you couldn’t get any decent sleep on what you did know.