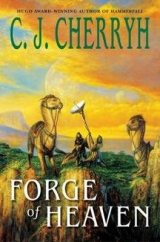

Текст книги "Forge of Heaven "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 29 (всего у книги 30 страниц)

“I shall have a talk with Luz when we get back,” Hati said.

“In moderation, wife.”

“Am I ever immoderate?”

A wise husband let that question pass unanswered. And in a moment more, Hati laughed.

The light grew as thunder migrated across the pans. And as they made the last climb to the ridge, a glance down and back showed a strange leaden sheen across the western part of the basin, a sheen that made the air above it thick with fog.

“Water,” Marak said. “Cold water.”

They had seen their new sea. It was coming, with a rapidity that made them glad they were getting off the ridge soon. If some weakness in the rock began to fountain water through the ridge they stood on, which by then would have become a dam holding the sea from the hollow Needle Gorge, it would be wise to make no long camps on the spine.

“Three days to reach safer ground,” he said. “And I think we should go there.”

15

TWO DAYS ANSWERING QUESTIONS, two days in which Procyon rested in a small hospital room with only the three robots for company; and then the two cleaner-bots strayed out when the meal cart arrived and failed to come back. They had disappeared into the ubiquitous cleaner slots, he hoped. He hoped he wasn’t involved in some Project notion of kidnapping the bots and taking them apart to see their circuitry. He still had flashes of dark, the illusion of smelling ammonia. He waked in sweats, with the sensation of a cool, spongy touch on his face.

He sat in front of the small room computer unit and played computer solitaire to keep from going crazy, while the remaining repair bot sat and watched him. He ate, he slept, he answered questions that popped onto the screen, and sometimes he heard one or the other of two competing taps fussing at him, trying to gain his attention. “Braziss,”one hissed, sending chills through his spine, and the other: “How are you doing, Procyon?”in a warm and maternal voice.

“I don’t know when I can see Brazis,” he answered the one. “I’m sorry.” And to the other voice, clearly a Project tap: “I’m doing all right, ma’am. No problems.”

He waited. He answered every detail he could remember, to occasional queries from the motherly voice. He didn’t ask about his sister, his family, or the other taps. He didn’t want to get any of them into more difficulty than they already had met on his account. Maybe that failure to ask was itself a problem, but if it was, it was his own problem, and he kept up that policy.

He slept again, and the repair bot was gone when he waked up. He worried about it. He never had named it: naming it had seemed to him to be a little crazy. But he had begun to think of it as a presence, and when it left him he felt strangely alone and depressed, at loose ends, even his endless solitaire games incapable of occupying his attention.

“Procyon,”a voice said. This time it wasn’t the woman he was used to. It was another one, younger, harsher. Authority.

“Yes, ma’am. I hear you.”

“The Chairman wants to see you.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

The Chairmanwanted him. It was a high-level disposition, then, not a quiet disappearance into the hospital and the security system. He experienced a little surge of hope that he hadn’t gone invisible, that he might still have some useful function. The wild surmise, which had begun to fade in recent days, that Marak himself might have insisted on his surfacing.

“Procyon.”Brazis, this time. Procyon stopped, in the act of dressing.

“Yes, sir. I’m sorry. I’m hurrying.”

“No great hurry. To relieve your anxiety, I’m satisfied with your answers. Everything’s fine. Now get in here.”

“Yes,sir.” He had a pair of pants, the ones he’d arrived in, cleaned. The shirt wasn’t in great shape, and he didn’t have a coat. He put on his shoes. Idiotically, pathetically, he missed the damned robot, which ordinarily would be sitting there blinking at him.

He got up, tried the door, walked out into the corridor and ran into uniformed Project police, to his distress. He said nothing, just went with the two women into the hospital lift system and, through a side hall, over to the restricted lifts, headed for the Project offices.

“HOW’S THE DAUGHTER?” Brazis asked Reaux, through Jewel, who had taken up her post in the governor’s suite of offices. “I hear she did phone.”

“You know too much,”Setha Reaux said to him peevishly, but not with great force, in Brazis’s judgment. A small pause. They had been discussing the departure of the Southern Crossfrom dock, an event greatly relieving a number of situations. “We’re meeting at a restaurant. Me, my wife. Kathy.Mignette, now. Tonight.”

“I’ve heard her mentor is counseling her to moderation. To go slowly. Plan carefully. She couldn’t be in better hands—where she is.”

“Where she is,”Reaux echoed him. “Which is better than where shecould be. I know that. We caught another of the group this morning.”

Brazis knew that, but let Reaux tell him, not to expose all his sources, or spoil Reaux’s triumph.

“In an apartment on Lebeau. Not a bad neighborhood,”Reaux added. “So I’m told.”

Across Brazis’s office, Magdallen sat, source of a great deal of information. Magdallen, with those green eyes and a dark good looks that probably got him more information than the police authority ever could, was still on the job.

“Listen,” Brazis said, “the reason for the contact: I’m setting Procyon loose. I don’twant him bothered.”

“I’ll make that clear where appropriate,”Reaux said. “Any resolution on the tap—hisor Gide’s?”

“Not much activity. It’s quieted down. The bots have disappeared, on their own. Gide’s become almost cooperative. Have you had any word at all from Kekellen?”

“Not a whisper.”

“So,” he said. “None here, either. I’ll keep you advised. Good luck with the dinner.”

“Good luck with your own business,”Reaux said, and Brazis tapped out.

“Vanish,” he said to Magdallen. “I’ll brief you later.”

“Yes, sir,” Magdallen said, stood up with a fluid motion, and left. It was sir,lately. It began to seem that, whatever Magdallen’s particular origins, related to the Council at Apex, his reports were going to reflect far better on Concord’s business than they had started out to do. The departure of the Earth ship—Mr. Gide irately refusing even to speak to the captain by phone—was a piece of information apt to be cherished there as it was here.

Magdallen left. Procyon Stafford arrived, coatless, a few rips on the shirt, not a physical mark on him but the tattoo, a mark all but invisible in the bright light of the office. Given the rapidity of the healing of other injuries, it seemed likely that that one visible trace was going to remain.

So the doctors said.

“Procyon.” Brazis stood up to meet the young man, courtesy to a person to whose resourceful escape they owed, collectively, a very great deal.

“Sir.” A reciprocal little bow. “Kekellen’s been very anxious I talk to you.”

“I know. The doctors have told me.” He found the young man’s worried intensity disturbing to his own agenda, and he walked over to his orchids, his source of calm and self-direction. It meant he didn’t have to look the man in the eye, or lie to him. “It’s likely, however, that that ship leaving—”

“It has left, sir?”

A damnable tendency to jump ahead. But the taps were bright. Too bright. Difficult to deal with, to keep under security restrictions.

“The ship is outbound, out of our lives. Mr. Gide remains hospitalized, not adjusting as rapidly as you. But then you’ve had practice.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Shall I be honest?” The young man’s candor urged him to it. “You’re stuck with that tap. There’s no way to remove it that wouldn’t damage you.”

“I rather well suspected so, sir.”

“It presents us a problem.”

“With Marak, sir.”

“Has he contacted you?”

“Is he all right?”

That immediate question, that question that wasn’t duty, concern that overrode all questions about his own future. There was a bond between those two. Kindred souls, if one subscribed to such notions. At least a bond that had formed and refused to be broken.

“I’ve asked Ian to inform him you were too sick to be consulted,” Brazis said. “The excuse is wearing thin.”

“He’s all right?” Right back to the essential question.

“He’s all right. So is Hati. They got the beshti back. They’ve rejoined their party, recovered their gear. They’re on their way back to safe ground, out of danger.”

A deep, satisfied breath. And no questions about his own future. It was hero worship, maybe. Or something stronger. One could envy the young man that kind of devotion. Or envy Marak, that he’d convinced a young man, who’d never see him face-to-face, that he was worth dying for.

And damn him, the young man had distracted him down his own path.

“Do you hear Kekellen now?”

“Not at the moment. But the bot left this morning.”

“You made that connection, did you, that that’s your relay?”

“I know there has to be a relay. I don’t think Kekellen would piggyback on yours.”

“Mine. As if I owned them. Don’t you feel they’re yourrelays, too?”

“I suppose they are, yes, sir.”

Brazis gave a humorless laugh, repositioned a bit of fake bark under a green, arching root. “I’ve damn near drowned these things in the last few days. Time they rested from our crisis.”

“Yes, sir.” Perplexity. Innocence.

But not naïveté.

“You know you’re a security risk,” Brazis said. “A tremendous risk to put you back on duty.”

“I know that, sir. And I wouldn’t risk him.”

Him. Marak. No question, still no protestation of his own ambitions.

“Your contact with Marak becomes an interesting question,” Brazis said, “since we’ll have some notion, via Kekellen’s tap, what interests Kekellen, what catches his attention. In a way, it may be a learning experience for both sides. Has he asked any specific questions?”

“He just said your name, sir, as if he had something to ask. Brazis, Brazis, Brazis. But there never was a question.”

“Maybe it wasn’t a question,” Brazis said, realizing that point, himself. “Maybe it was a direction he was giving, for your safety. You’re Marak’s tap. You were threatened. Kekellen didn’t want the program disrupted. Didn’t want Marak inconvenienced.”

“You think that was it, sir?” Hope, but a great deal of doubt, with it.

Brazis had his own hope. Kekellen was odd, but he had never demonstrated himself aggressive.

“It’s a new age in communication, isn’t it? If he’s talking through that tap, if it isKekellen, one can assume Kekellen has internalized a tap of his own. Does that thought occur to you?”

“I’ve heard him breathing,” Procyon said. “It sounds internal.”

As taps from inside did sound…internal. Like one’s own voice. A man who used the device routinely knew that very well.

“Interesting. But he doesn’t get onto our system.”

“I haven’t caught him trying it, sir. I don’t think he does.”

“You’re the junction point. Gide doesn’t own another tap, even the common one. But Kekellen may ask you questions sooner or later. And expect you to relay things to Marak. I wouldn’t be surprised.”

“I suppose he will, sir.”

“Likely that bot will show up when he wants to talk or listen. They get through interfaces in the walls. Places you have to get an architectural diagram to figure out. All sorts of passages that in ourdiagrams don’t connect. But repair bots, I suppose, can make little changes we don’t know about. Build new routes. Connect others. One wonders what archaeology of the stuff behind the walls could show us, on the former stations.”

“I don’t know, sir.”

The perfect subordinate answer. The opaque answer. But nobody had investigated. The structure of the stations had been on record for ages past. No one ever questioned it not being what was on the charts. Robots did all the internal service work.

“Well, well,” Brazis said. “It’s all outside your concerns. Except I want a report the minute you find a bot tagging you.” It was going to take a little monitor inserted in Procyon’s apartment, one that would find intrusions Procyon didn’t know about, behind his walls. It was going to be an interesting few decades, his administration.

“Yes, sir,” Procyon said.

“Drusus and Auguste have gone back to work. They’re still limiting their activities. The doctors don’t want them on longer than an hour on, an hour off. We’re monitoring via Hati’s taps. How do you feel?”

“No effects, sir.” A spark of fervent interest. But then a little hesitation. And, worriedly: “I won’t contact Marak if I think in any way I’m a conduit for Kekellen.”

“I think we can work that out. You’ll help us. Marak will. He understands your situation.”

“He does, sir?”

“He’s not entirely pleased about what happened to you. But he’s happier now that you’re on your feet. Are you fit to go on duty?”

“I’m fine, sir.”

“An hour on, an hour off, until you hear otherwise.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Dismissed, then. Go to it. It’s your shift.”

“Thank you, sir.” Procyon started to leave. Then stopped. “Where do I go, sir?”

“Home,” Brazis said. “Home to your apartment, I suppose. Where your office is.”

“I’m known on the street, sir.”

“I’d say you are. You’ll have to manage that notoriety. I leave that to your ingenuity.” A deliberate frown. “And wear a coat in the office.”

“Yes, sir.” Enthusiasm. Boundless enthusiasm. As if he wasn’t a walking communications device for Concord’s most dangerous resident. “Thank you, sir. Thank you.”

“Out,” Brazis said. Gratitude embarrassed him, when simple necessity had dictated the young man’s return to work. Keep Marak happy, repair the breach downworld. Keep Kekellen happy—maybe let the old sod ask a few direct questions of Marak, if Marak would deign to answer them.

The one honest man on earth. And Kekellen had found honesty in the heavens, it seemed.

Honesty didn’t figure in his own duty. He just did it as he saw it.

DINNER AT THE PLANE,not the place Procyon would have chosen, but Ardath had her standards and her obligations. Procyon wore his best, quiet, against Ardath’s blue and gold. The maître d’ whisked him to a conspicuous table, saw him seated, and the wine steward was quick to put in an appearance, suggesting his own mid-pricey celebration favorite. Ardath had arranged that, and he didn’t fight it. He sat pretending he didn’t know the whole room was watching and waiting. He hoped it might be a one-drink wait if he was lucky.

And Ardath swept in early, with Isis and Spider, with little Mignette in close, worshipful attendance. Isis, Spider, and Mignette weren’t sharing the table. They had another. But they were always nearby, Ardath’s bodyguards, if the need for defense ever presented itself, social or otherwise.

He got up, returned his sister’s warm handclasp, sat down again with the whole world watching.

“You’re looking good,” his sister said. A thousand hopefuls would die for that judgment. He only resisted the temptation to touch the brand he wore forever, in front of all these people.

“You’re always good,” he shot back, and made her laugh.

They dealt with the wine steward, and with the waiter, and with the owner, who would have fired either the steward or the waiter if they had either one so much as frowned.

It was too much steady smiling. They heaved a simultaneous sigh as they finally found something like a moment of privacy, the two of them alone.

“How areyou?” Ardath asked him, meaning a world of things, and he gave a little shrug.

“Well, I’m supposed to visit the parentals on the 12th.”

“Poor brother!”

“Oh, I’ll be completely respectable. Except this.” A little shift of the eyes upward. “Except they know, now. The street knows. And they do. It’s going to be interesting.”

“I can’t go.” It was an earnest, worried excuse. Halfway an offer to have gone in his place—if she could.

“Sis. You’re sweet. But I’ll survive. More to the point, I won’t scandalize them if I stay in bright light, and I’ll play games with the junior cousins. I’ll be just cousin Jerry.”

“Horrid. You aren’t. Everybody knows you’re not.”

“I am. More than you’d guess. I just live my little life and buy my own groceries. It’s my private fantasy.”

Ardath set her chin. “The fools on this station can’t touch you. Nobodydares touch you.”

“Security doubts they would, at least.” Salads showed up, deftly, quietly. “And you? How are you getting along?”

“Oh, fine,” Ardath said. “Really, very.”

“That’s good.”

“Procyon, do you haveto live at that stodgy nook address?”

“It’s comfortable.”

“Well, you lend it cachet. No question. They couldforgo the rent. You should speak to the management.”

“I’m kept by the government, but don’t spread that around.”

A laugh. “I always knew you’d do something sensible.”

Kekellen listened from time to time, but said very little. Unlike Marak, Kekellen observed no schedule, interrupting his sleep now and again, but mostly keeping his robots away and his relays quiet while he was working or in public, and he was glad of that.

Drusus was on duty at the moment. They were back in the usual rotation. So he had a private life, such as it could be, with such ties as he had. He actually enjoyed the supper, feeling safe, in a way he hadn’t expected. There were two kinds of security, one he’d kept by being nobody and quiet, and what he had now, a notoriety that made people shy of talking to him, let alone bothering him.

That meant he could do what he’d never done, and go where he’d never go, and he didn’t have any question he’d stay employed—not these days.

He’d begun to settle in, was what. He’d found a means of living the life he liked.

That wasn’t at all bad.

THE AIR HAD a different smell, now, wet sand, wet rock, salt water; and the evenings had gotten much colder.

Change, change, and change in the rules of the world. Marak took a steaming cup of tea, and Hati took one, and they listened to young Farai, who thought he’d seen a fish swimming at the surface of their new sea, and was excited.

Marak himself doubted any fish could survive the plunge the watchers in the heavens described at the gates of the Wall. But who knew? He listened politely, and drank his tea.

The long spine of the Needle Gorge was indeed likely to fail, so Ian said, and soon, taking their relay with it. Well that they were up on solid ground. And they might almost see it from here.

Luz was back with Ian. The Ila had taken to her quarters, with the doors shut. They might stay shut for a while.

Ian’s latest rocket was a success. Ian was getting spectacular images from the Wall, which now stood as an island, and they got others, from the edge of the plateau. They sent them to the Refuge, but the Ila refused to come out of her chambers and look.

Ian had tried to entice him to come back, meanwhile, but he was uncertain. Out here, he had no need of Ian’s cameras. To see all the history of the waterfall in its glory, it seemed they had a choice, to go back to the Refuge, or at least trek as far as the waystation at Edina, to see Ian’s images on a much larger screen.

Meanwhile the shallow rim of their new sea steamed with fog, while the heart of it deepened. The waterfall at the Wall had diminished, the seas equalizing.

As for Farai’s precious fish, first would come the chemical adjustment of the water, the algaes, and the weed would take hold, and the one-celled creatures, and the floaters and the burrowers.

Once the food chain established itself, then the fishes might come, long and sinuous, making their living on lesser creatures.

Already the weather reports spoke of torrential rains in the highlands, water which would cut the gorge faster and faster toward the new sea, until it vanished altogether into a chain of islands. When the Needle did merge with the sea, it would sweep down its own different chemistry to a new estuary.

Everything was a chain. And there were thousands of new things to learn.

“I think Farai is imagining this fish,” Hati said.

“I all but know he is,” Marak said quietly, but he never would deflate the boy’s enthusiasm. And, who knew? One might have ridden out the chute.

They were bound for the east, now, at a leisurely pace, while Meziq’s leg mended. The watchers in the heavens were back at their posts. The ondat,the Ila’s great enemies, had established their own tie to the watchers, but Procyon swore it was no great inconvenience to him; and meanwhile the ondat,like everyone else in the heavens, simply watched—absorbed, perhaps, in the news of a new sea, new weather, new wonders, in closer relationship with the world than before. There would be no war in the heavens, nor any more troubling by the Earth lord, who had settled into quiet, likewise touched by the ondat.

Hati understood the close call they had had. His youngest watcher went on adapting, having the good sense to deal softly with the ondat,having all the joy of life in him since his return, describing all the images he saw of the incoming sea.

He could hardly imagine where the boy was at the moment, in a building, in a structure, with this sister of his, at a celebration. Procyon was happy, and new as the morning: that was the bond they had between them. He had sons—he and Hati—sons and grandsons and great-grandsons in great number, besides their descendants; they were all familiar to him.

This one held surprises. Like the desert. Like the sea. This one broke the rules wisely. Like him. Like Hati.

Such a life was a treasure, when it appeared.