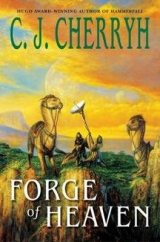

Текст книги "Forge of Heaven "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 30 страниц)

5

THE TRACKS HAD tended down along the terraces, over drifts of sand, then grown dim on sandstone. Marak and Hati looked for signs at several opportunities for their fugitives to have taken another downward path, but they found none. The wind-blurred traces led instead across a vast flat sheet of sandstone, staying on their level. This gave them hope that if the dust should settle a little, they might catch sight of the group. They quickened their pace.

They advised the Refuge to advise the camp. The relay had gone up. Auguste said so, and communication had now become reliable. “The leader of this band,” Marak said, “will be skittish. This may take a while.”

His own old bull would not have bolted repeatedly and zigged and zagged along the terraces. The young one had. And the herd, indecisive as their new leader, veered slightly southward now, generally down the long spine, still on this level of the terraces. Sandstone spires rose ghostly and strange in the lingering dust, and generally obscured their direct view of what was ahead, even had lingering fine dust not hazed the air.

Marak had faith that even the spookiness of a new herd leader had to steady down with repeated tremors. But right now their young bull would bolt at every shaking in the earth, every breath of wind, taking the females farther and farther from the old bull he had robbed, and would do so until the females grew annoyed with his skittishness and grew slower and slower to follow. Beshti had their quirks, but they were predictable in their ways.

About the watchers in the heavens, however, Marak was just a little concerned. He expected Procyon, in the ordinary cycle. He discovered he had Drusus instead. Something strange had happened in the earth, and now something else strange had taken place in the heavens, at a time when he most wanted his information flow to be ordinary and dependable. First his contact had gone on and off, intermittent in the storm. That had steadied, and now other things seemed unreliable.

“Is Procyon well?” Marak asked Drusus, when first he came in clear. “Is he taken ill?” Hati expressed her concern, too, to her watcher, Carina, who joined her uninvited. That was the measure of worry on Ian’s part. They suddenly had watchers left and right, Hati’s called back to duty, but his not the one he expected.

“Brazis has sent him on an errand today,”Drusus answered his inquiry. “A request from an Earther lord. Earth seems concerned with his appointment because of his young age. Procyon will pay his courtesies to that person and return, either today or tomorrow. The Earther lord is considered benign. There is no reason for worry, and this is an inquiry, not a matter for concern. I hope, omi, you will accept my being here early, today.”

“We understand,” Marak said, to end the protestations. He was, at the moment, at a difficult traverse, on a strip of sandstone scarcely wide enough for safety. He had his answer, but he remained annoyed and just a little suspicious—halfway moved to demand Procyon’s immediate attendance, never mind the affairs of lords in the heavens, who had no right to demand the attendance of persons who lived under his personal protection. He knew about Earther lords, he had experienced them, that they were prone to nose about and interfere where they could. And this request was damned ill timed.

Lords and directors came and went in that place in the heavens that by all description was like the Refuge, all corridors, plain walls, and lights, with here and there a garden, by what Marak had gathered. There the ondat,too, once hostile, thanks to the sins of the Ila, lived and watched over the world with some suspicion, still dangerous—but Earth, at some distance, being the birthplace of all humans and even the beshti and no few of the now-extinct vermin, thought its history gave it a special right to send out its governor to rule this metal world.

So the Ila said, along with much else he had read in the Books of the Record.

But Earth certainly picked a time of great nuisance to make its demands. He knew his own right not to be annoyed by what happened above—particularly where it regarded his watchers. He wanted Procyon with him today—the cheerful young watcher who even in his routine weather reports managed a heartening enthusiasm. Drusus was the director’s man, full of rules and cautions. He had the niggling suspicion someone thought Drusus was the watcher he should have right now, since the quake—and that suspicion more than annoyed him. If he thought the boy’s inexperience would be a hazard, hewould make that call. He was determined not to blame Drusus for the situation, but he could blame Brazis, when he had time, because he was not at all sure there wasan Earth lord.

Meanwhile, however, he could try to moderate his temper and find out the truth of what was going on.

“Procyon is paying court to some Earth lord,” he told Hati, who could be overheard, but who could not overhear Drusus. “No long venture, so Drusus assures us. He’s come in early to fill Procyon’s place.”

“So,” Hati said, frowning. Hati was an’i Keran, Keran tribe, quick to the knife, even in these latter days when the land grew wider and water was no longer a matter of dispute. “Today of all days, and without consulting us. We can well remember such favors.” Let the director and the Earther lord hear that. Hati had an opinion of her own, and, unlike him, felt no obligation to be reasonable.

They were neither of them happy, at the moment. They had another aftershock, and their fugitives took out down a slope—they came on the tracks, a wide wallow in a breakneck sand-slip. There were no beshti lying dead at the bottom, which argued they had made it.

But it was a chancy ride, and they had to do it. They worked their way down, and tracked the runaways southeastward, while Drusus kept prudent silence.

The wind was less down here, at least, and haze was less in the air, but they had been cautious coming down, and their fugitives almost certainly opened a wider lead, breaking low brush—a sparse, low-lying spiny growth that spread like fingers from a single plant, and branched and rebranched among the rocks and on the sand, putting down new roots—a warfare like that of nations, vegetative dueling for broader and broader territory. The weed actually poisoned the ground to discourage its competition, and made a thick mat that cracked and broke as their beshti crossed it, behind others that had cracked and broken it in passing. Beshti, who ate most things, found no attraction in this stuff, which the Refuge had never chosen to seed, but which survived and thrived since the hammerfall. And now it helped obscure the ground and made footing less certain in precarious places. It hid holes and crevices.

“Prickle-star,” he said to Drusus. “It smells like graze and burns the tongue. One of the worst things will thrive, and the succulents gain no foothold here, in consequence.”

He felt another aftershock coming. The beshti felt it. It was a hard shaking, and long.

“Stronger than the last,” Hati said.

The young men up on the spine, minding the tent, were surely getting an education they had not expected on this tame journey.

And their fugitives, invisible among the spires, would not have stood still.

“Another quake,” he said to his watcher.

“Are you all right?”Drusus asked him.

“Well enough,” he told Drusus, amicably. “It was stronger, however.”

Hati was used to him talking to his voices in moments of crisis. She talked to her own, today, and told her watcher to let her alone, that there was no difficulty. She was never patient with them. They reached a place of vantage, above the dust-hazed depth of the pans. And an area of darker dust showed in the haze below.

“Can you see them?” he asked Hati. Hati had risen up with her knees on the saddle in their pause, to have a look with a collapsible glass.

“Yes,” Hati said. “Well away down the slope, toward the next terrace.”

“Where are you, omi?”Drusus asked.

“Two terraces down toward the pans,” Marak answered, and tapped his beshta with the quirt, as Hati dropped down to the saddle and put away the glass. They both started down.

“Have the beshti gone off again?”Drusus asked, annoying him with questions.

“What else would beshti do?” he answered shortly, then amended the answer. “They have gone down, risking their necks. The gorge rim was too steep for them. This is not.”

“It’s too dangerous to go down, omi,”Drusus told him. “ The quake was not minor. Ian believes the Southern Wall is about to fail.”

It took a moment to reach his attention. Then did. “Ian thinks the Southern Wall may have cracked,” he said to Hati, but he thought she might have heard it from her own watcher. Her jaw was set in a deep frown. And he abandoned his annoyance with his watcher. “Is it breaking where we thought, Drusus?”

“The epicenter was out under Halfmoon Bay.”

“It was at Halfmoon,” Marak said, for Hati—all he needed say to convey extreme chagrin, because the Halfmoon area of the Wall was their planned destination, the point where the spine they were on intersected the Southern Wall.

It was the site they had thought would be a safe place to set the next relay.

“Observers are less sure now how or where the Wall will crack,”Drusus said to him. “Don’t go down into the pans, omi. The director thinks it best you come back up to camp and let Ian send a mission out from the Plateau, not with trucks. He says he can put Alihinan aware and have his riders bring beshti to your camp….”

And have someone bring more beshti up from the Refuge to Alihinan, clear up on the Plateau, on the other side of the Needle. “Which will take a while. If the Wall has cracked, the spine itself may grow unstable, and we have a man lying in camp with a broken leg.” His beshta’s descending strides jolted under him, a chancy descent of a loose, sandy slope. “We stand a better chance by catching our runaways.” As haze wrapped them about, obscuring all but the solid shapes of the sandstone spires. “Has the Wall shown a breach?”

“Not yet.”

“Then tell me when it does.”

“Omi, when it comes, where it comes, they think now it may become a far faster, far wider breach. An entire section of the Wall may fail at once. The displacement in that first event may have been as much as ten meters.”

Drusus’s usual stolid, quiet voice was not stolid or happy at the moment. A cataclysm of icy water was portended to break through, not far to the south, but right where they might have been standing, if they had been a number of days further advanced on their trek. They would have been camped on the Halfmoon section of the Wall, setting up their relay when it changed relative elevation by ten meters.

Maybe there was reason the director had moved Drusus up in the daily sequence.

“Ian says he is this very moment preparing a rocket,”Drusus said, “to soft-land a relay at Halfmoon. You have no need to go on.”

Ian had hadto relay that to him. They had disputed the matter of the rocket hotly before he left, he and Ian, Ian intent on using their sole prepared rocket to set down the relay, before establishing fuel dumps and small manned way stations to take various missions there by truck, a very quick process on one end and a very slow business of establishing a land route on the other, a three-year program with trucks making successively more distant fuel drops, and getting to the Wall eventually. Machines had to be supported by more and more machines. Sand buried fuel dumps. Fine dust found its way into intakes and engines. Landbound machines broke down. Flying ones crashed in inconvenient places and someone, usually with beshti, had to trek after their irreplaceable metals. Marak maintained he didn’t need three years to prepare the way for a small, self-sustaining caravan. He could get a firsthand look at the Southern Wall while Ian was still getting under way, and without risk of an airplane or expending another rocket in a very chancy and rocky area.

He would have been right—if he hadn’t lost the beshti. If he’d used Ian’s metal-centered cable to secure the beshti, instead of softer, safer rope.

If, if, and if.

He hated it when Ian was right. He could limp home with the two beshti they had and all his party could survive with limited canvas. He could give Meziq the makers, set the leg, and have it healed before they got down off the spine.

But they weren’t that far from their fugitives, and they weren’t beaten yet.

“Ian is urging us to take the conservative course and walk home, and perhaps, eventually, someone will meet us with beshti,” he said to Hati, their two beshti side by side for the moment. “He says the Wall will crack at Halfmoon.”

Hati shrugged. “So Carina says.” Naming her own watcher. “Ian is launching his rocket. Likely we shall still set up our other relay ourselves, after Ian’s silly rocket sits down on a rock, like the last one. Several caravans can carry back its metal, if it survives the flood.”

“They want us to go back upland and give up this chase.”

Hati looked across at him, with those beautiful fierce eyes.

“I don’t think so,” she said.

THE GOVERNOR’S OFFICE was entirely terra incognita. Procyon walked a corridor where he had never in his life looked to go, a hall lined with doors reputed to be antiques salvaged from ancient governors’ offices on prior Concord stations. They were carved in flourishes, and might even be real wood, not plastic. The vases in the niches were definitely imports, maybe antiquities, too, the sort of objets d’art that even his mother wouldn’t put flowers in. The reds and blues were deeply glazed, the gilt amazingly bright. He tried not to look impressed.

Glass doors protected the end of the corridor, clear and thick, and probably able to go opaque at the touch of a button. They said, in lettering that hung glowing with an iridescent water-pattern in the glass, SETHA T. REAUX, GOVERNOR OF CONCORD.

Those doors admitted him without his doing a thing but approach them. A second set of doors, also antique, let him into an inner office where a thirtyish official—tall, blond man, prim sort, with close-set eyes, and nothing, absolutely nothing but a bud vase on his desk—looked him over as if he’d come to steal the silver.

“Mr. Jeremy Stafford,” the man said.

Not even Brazis called him his registry name. But he was, in fact, Jeremy Stafford Jr.

“Yes, sir. I’m supposed to see the governor. Chairman Brazis asked me to come.”

“The governor is expecting you,” the man said. “Go on in.”

The inner door slid aside for him. With the feeling he was going behind more doors than he possibly liked, farther and farther from familiar territory, he walked in, onto fancy import carpet, facing a stout, gray-haired man he’d only seen on the vid.

It was a surprisingly small office, with amazing antique furnishings. A huge life-globe. He couldn’t forbear looking at it once, and again, seeing a small movement inside. Antique printed books, in massive shelves.

Reaux rose from his desk, offering a welcome, a little nod, if not a handshake, and Procyon’s instant thought, on looking into the man’s face was, He wants help, and he really hates doing this.He gave his own little bow—you never reached for an Earther’s hand: they went into hysterics—and produced as friendly a smile as he could manage, given his situation.

“Mr. Stafford,” Reaux said. “Thank you for coming. Do sit down.”

“Yes, sir.” He sank into the opposing chair, hard, but padded. The dark brown leather under his hands might be real.

“Brazis says you’re one of his best.”

“One of his newest, sir. I hope I do my job.”

“I understand you were a Freethinker.”

God, was that the issue? “I attended a couple of meetings when I was a kid. I left. It was my idea to leave.”

“In the remote past.”

“Remote, yes, sir.”

“Six years ago.”

“I’m twenty-three, sir. Not to be argumentative, but six years is a fair number of years ago, out of twenty-three. I was sixteen, seventeen, then, and stupid.”

“I hope this particular curiosity is now satisfied.”

“I didn’t agree with their ideas. I think they’re wasting their lives.”

“Attracted by the Freethinker style, then?”

“No, sir, by the ideas, on the surface, but when I got to hear the details and the reasoning, I didn’t like what I heard. And I haven’t had anything to do with them since.”

“Sixteen. And interested in the ideas. You were remarkably precocious.”

“I was curious. But I didn’t agree with them.”

“What did they say, in particular, that you didn’t agree with?”

Shaky ground. He wished now he’d skirted this topic with more determination, but didn’t see how. “They talked about justice. But they were more interested in debating their own rules. And they cheated in their own elections. How were they going to give justice to anybody, if they cheated to get into power?” It was out of his mouth before he realized he was talking to an elected official. He wished he hadn’t said that last.

“A sensitive young man.”

“I don’t count it any credit to me for being there. They’re not what I wanted. Not what I want now. That’s completely done with.”

“You have a tremendously important position these days. One naturally, yes, does understand the curiosity of youth. The flirtation with ideas. That’s even commendable. Seeing through them, more so. But let me be very frank here. If you have any lingering acquaintance with anyone in that organization, I earnestly advise you tell…not me. I know I can’t ask you for that level of honesty. But tell your Chairman. This is extremely serious. At very least—if you even remotely know someone in that organization, don’t contact them on the street for the next four days. If I could make a request—don’t entertain or be contacted by anyone with ties in the Trend oron Blunt for the entire duration of this ship’s visit to Concord. Their monitoring may be extensive, and you wouldn’t want to give them any false impression of you.”

“I understand, sir. I have no friendly contacts among the Freethinkers. And I have no trouble agreeing.”

“Has the Chairman told you there’s a political development involving you?”

“That the ambassador wants to see me, yes, sir. The Chairman told me that.”

“Chairman Brazis apparently believes you might successfully carry off a little inquiry. That, doing the job you do, you’re smart enough to avoid saying anything provocative while you’re there. He also says that you have considerable powers of recall.”

“I’m not allowed to talk about my job with anyone, sir, I’m sorry.”

“You are a tap.”

“I can’t talk about what I do, sir.” By his tone, the governor, curiously enough, seemed to list the tap among his assets. Most Earthers felt differently.

“A particular kind of tap, allowing you to do the very important job you do—which at governmental levels we do know, Mr. Stafford, and have no interest in creating difficulty for you.”

“I’ll have to tell the Chairman you asked me, sir, with all respect.”

“You acquired this tap after you left the Freethinker orbit and you trained to use it, so successfully so you are where you are. Is it active now? Could it be active now, if you wished?”

“I’ll convey that question to the Chairman, sir. When I leave this office.”

“I’d like to ask the Chairman a question.”

A little harder jog of the heart, a warning. “No, sir. I won’t say what I can and can’t. But I’m not a tap-courier and I don’t mediate messages.”

The governor gave a slow smile. “Brazis said you were no fool.”

A test of his discretion. If there were secure relays here, in the governor’s own office, he wasn’t aware of it, and he wasn’t going to tap in here and now to test it. “I try not to be a fool, sir.”

“Has the Chairman indicated to you that he doesn’t trust my office security?”

“No, sir. Not to me, he hasn’t.”

A little frown of annoyance or thought, then a smile that seemed somehow more genuine than the one before. “I’ve had it gone over minutely. I don’t find any relay. But you can tell Brazis I and my security are a little annoyed at the fact a tap-courier can operate here.”

“Yes, sir.” That one could was news to him.

“Are you cut off from contact with Marak at the moment? I’d certainly hope that’s the case.”

“Again, sir, you’d have to ask Brazis about that.”

The smile hardened. “Again, Mr. Stafford, you have very good instincts. I’m impressed. So. Let’s get down to business at hand. Mr. Andreas Gide has come all this distance specifically to see you, it seems, and Brazis is agreeable to that interview. We’re both curious what this off-schedule visitor is up to, and what he thinks you represent. We both recognize the danger you may run in going in there, not utterly discounting any physical danger, but I doubt it. So does Brazis. Let me supply you other facts, which a young man of your political awareness can surely take to heart. This isn’t a scheduled ship-call. It came as a complete surprise to us. This high-ranking person purposely travels an extreme distance, at extravagant expense, and his first request is to see the youngest, newest tap connected to Marak himself, a tap who happens to have a Freethinker background, however far and faint in his past. I’d be far more comfortable if you had never visited a Freethinker den—if I could send him a young man with no past entanglements. But that’s not the situation we have, is it?”

“No, sir, but it is far in the background.”

“Do you comprehend that the repercussions from any mistake, any slip of critical information, could be extreme in this affair? That I have great misgivings in sending a twenty-year-old, no matter how intelligent, to handle this? Your mind is probably extraordinary. I’m very impressed. Your experience, however, is limited. And this man is very sharp.”

“I can’t imagine what this man wants from me, but I know one thing. I can’t contact Marak for him. The Freethinker business is done with, it’s no secret to the Chairman, and I can’t be black-mailed or surprised in that. In the main, sir, I don’t know anything particularly secret. There are a lot of people in the Chairman’s office he could have asked for that have data on the Project. But I doubt they’d be volunteered for this. The only thing that bothers me is that I don’t see why he’d settle on me, except maybe he thinks he’s got something on me in the Freethinker business, or that I’m new on the job and he thinks he can intimidate me.”

“ Canhe intimidate you?”

“No, sir.” No hesitation. He was very sure where right and wrong lay, by the sacred Project rule book. And he wasn’t required to do anything but show up and avoid answers.

“I hope you can report to me what questions he asks.”

“Chain of command, sir. I report straight to the Chairman, and that’s exclusively where I’ll report unless he instructs me otherwise. You can ask him, and he might let me debrief here.”

“Smart young man. Remember what the ambassador asks even if you don’t understand the question. Remember exactly what he says, the very words, and manage not to answer him. He isfluent in your native language. You may not appreciate how extraordinary that is. But it indicates to me that he came here well prepared for this interview. Say as little as possible. Claim you have to consult: you do. Set up a second meeting if possible, which may give your Chairman and me a chance to confer in the interim.”

He was supposed to miss one session with Marak. Not five. Not ones after that, in endless debriefings. It was an appalling prospect. He didn’t want to be used for this. But he didn’t say that. “If the Chairman agrees to that idea, sir.”

Reaux pushed a button on his desk. “Mr. Chairman?”

“I’m following this.”It was Brazis’s voice over an ordinary phone. And Procyon knew, first, with a little jump of his heart, that he’d sat here, with all his confidence, failing to detect he’d been spied on, by such low-tech means and by an Earther. But he was sure, his heart subsiding to a more confident beat, that he’d said absolutely nothing he shouldn’t. He lived under observation. He was, in that sense, used to it, never knowing, when anyone talked to anybody in the offices, whether they had a tap, and whether somebody not present was hearing most of it. Brazis had warned him explicitly about truthers. But he’d passed. He hoped he’d passed.

“Procyon.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Voices can be synthesized. You should constantly remember that.”

Deep blush. He felt his face go hot.

“Yes, sir.”

“I agree with the governor: arrange a second meeting if you can. I’ll confirm all these instructions later, so you can be sure they’re mine.”

“Yes, sir.”

Not only physical lines, in dealing with Earthers—a trick he hadn’t straightway thought of—but physical tricks he’d not had to worry about, either, in discriminating truth from lies, like faces and voices that weren’t real. Earth didn’t use taps, but he’d always heard Earthers had tricks. Faking identity was a near impossibility where the secure taps were concerned. But among Earthers, behind the governor’s doors, where there were no secure taps, proving one’s identity, yes, had to be a major concern.

“An escort will pick you up tomorrow morning at 0900h,” Reaux said to him.

“Tomorrow.” He’d already missed today. “And, sir, the Chairman won’t want attention drawn to my apartment—”

“—at your area lift.”

“There are two. The one at 11th and Lebeau. It’s far enough away.”

“The 11th and Lebeau station, promptly at 0900h. You’ll know my man by a code word. He’ll call you Mr. Jones when he meets you. He’ll take you to the ambassador. Dress modestly, as you are now. The ambassador’s name, again, is Andreas Gide: you can call him Mr. Ambassador, or Ambassador Gide, or just plain sir is quite adequate. He’ll assuredly try to unsettle you. He’ll almost certainly confront you about your past associations. Be prepared, but don’t be glib. Let me warn you in advance, his appearance is imposing. You’ll face a plastic display, a chemoplasm on a containment shell, which may have unguessed sensors and recording devices inside, and truthers, but don’t try going in on sedatives. That always shows. At all points, you’ll have Brazis’s protection, so rest assured, Gide can’t harm or threaten you: he’d fear the consequences, in terms of international law and Treaty law. Brazis is relying on that point, extremely, and so am I, in principle, so I want you to understand what is at risk. Unfortunately in certain departments this ambassador outranks me, so it’s not likely I can help you if this goes badly. At all points, listen far more than you speak, and encourage the ambassador to talk. Draw him out, if you can.”

“I understand.” He wasn’t sure he did have the full picture of what he was up against. But he saw he had no choice. He wanted to get through this. He wanted it over, for more than just getting back to the business on the planet. He wanted himself back in his own life where he belonged, safe and out of reach of powerful strangers.

“Thank you, Mr. Stafford. I very much appreciate your cooperation.”

“Sir.” He rose and gave a little bow, understanding he had just received his cue and the interview was over. “Tomorrow. 0900h.”

Trouble now, trouble of all sorts if he didn’t handle this well, and meanwhile all hell had broken loose on the planet, and he only hoped Drusus had told Marak it wasn’t his choice to be absent right now. But he couldn’t even choose his own cover story: he’d have to learn it from Drusus, and he’d have to live with it. Business behind the security wall wasn’t something he could explain to Marak later—since they weren’t supposed to inform the planet about the station, or about its politics, and this certainly fell under business behind the security wall. If Drusus didn’t handle it right, he could find everything on end and Marak mad at him when he did get back on duty.

But it was no place to think of that. He paid his courtesies solemnly, received the governor’s polite acceptance, and made his exit past the secretary, not happy, no.

He walked out down the corridor and into the general administrative zone, where he thought there might be tap relays if there were any on this level. There he made the blood shunt in his skull, the coded single long effort that contacted Brazis’s office.

Brazis himself had several aides who shared one of his tap codes, aides who took notes and handled what amounted to nuisance calls from workers who didn’t quite have the level of emergency they thought they had—or sometimes handled real emergencies that Brazis couldn’t get to fast enough.

“I want to talk, sir,” he said to the empty air, conscious as never before that there might be physical eavesdroppers or lip-readers around him, picking up his side of any conversation. “This is Procyon.” He walked quickly for the lift, and then thought that, too, was audio-and video-monitored, particularly if the governor was tracking someone. Computers once set on his trail could track him through every common tap relay in the station. Whether that had any physical connection with tap relays that weren’t supposed to be operating up here, he had no way of knowing. “I’m going to the lift, now. I’m anxious to talk about this. Instructions?”

No answer. Either he wasn’t getting through because there wasn’t a Project relay in this area, or nobody in Brazis’s office wanted to talk to him here. He caught the lift down to more general territory, changed to a common public lift where he knew for a certainty there would be secure relays and little likelihood of spybots.

But he didn’t make a second try at Brazis’s office until he was safely down in the thick foot traffic at Seventh and Main, on his own level, where Outsiders alone maintained everything that needed maintaining, and where any Earther attempt to bug the place would meet quick detection and entail nasty repercussions.

Then he didn’t have to try to reach Brazis. Brazis found him.

“Procyon.”

“Sir.”

“Good job up there.”

“Thank you, sir.” His heart pounded.

“What he requested you, do. This constitutes your confirmation. I did hear the conversation—mechanically speaking.”

“Yes, sir.” Considering there was still a danger of lip-readers or listeners, he just listened to the tap, which no one without a tap from the same source could get into.