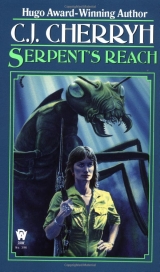

Текст книги "Serpent's Reach"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

BOOK FIVE

i

“The old woman has something in mind,” Tand said. “I don’t like it.”

The elder Hald walked a space with his grandnephew, paused to pull a dead bloom from the nightflower. Neighbouring leaves shrank at the touch and remained furled a moment, then relaxed. “Something concrete?”

“Hive-reports. Stacks of them. Statistics. She may be aiming something at Thon. I don’t know. I can’t determine.”

The elder looked about at Tand, his heart labouring with the heavy persistence of dread. Tand was outside the informed circles of the movement. There were many things of which Tand remained ignorant: must. Where Tand stood, it was not good that he know…near as he was to the old woman’s hand. If the blow fell, all that he knew could be in Moth’s hands in hours. “What kind of statistics? Involving azi?”

“Among others. She’s asking for more data on Istra. She’s…amused by the Meth-maren. So she gives out. But here’s the matter: she muttered something after the committee left. About the Meth-maren serving her interests…conscious or unconscious on the Meth-maren’s part, I don’t know. I asked her flatly was the Meth-maren her agent. She denied it and then hedged with that.”

The Hald dropped the dry petals, his pulse no calmer. “The Meth-maren is becoming a persistent irritant.”

“Another attempt on her—might be advisable.”

The Hald pulled off a frond. Others furled tightly, remained so, twice offended. He began to strip the soft part off the skeleton of the veins. It left a sharp smell in the air. “Tand, go back to the Old Hall. You shouldn’t stay here tonight”

“Now?”

“Now.”

One of Tand’s virtues was his adaptability. The Hald pulled another frond and stripped it, trusting that there would not be the least hesitation in Tand, from the garden walk to the front gate to the City. He heard him walk away, a door close.

His steps would be covered, cloaked in innocence…a supposed venture in the City; and back to Alpha, and Old Hall. There were those who would readily lie for him.

The Hald wiped his hand and walked the other path, up to other levels of the Held residence at Ahlvillon, to east-wing, to other resources.

A pattern was shaping.

On Istra…things had long been safe from Council inspection. Communications had been carefully channelled through Meron, screened thoroughly before transmission farther.

He walked the balls of panelling and stone, into the shielded area of the house comp, leaned above it and sent a message that consisted of banalities. There was no acknowledgement at the other end.

But three hours later, a little late for callers, an aircraft see down on the Hald grounds, ruffling the waters of the ornamental pond.

The Hald went out to meet it, and walked arm in arm with the man who had come in, paused by the pool in the dark, fed the sleepy old mudsnake which denned there. It gulped down bits of bread, being the omnivore it was, its double-hinged jaws opening and clamping again into a fat sullenness.

“Nigh as old as the house,” the Hald said of it.

Arl Ren-barant stood with folded arms. The Hald stood up and the mudsnake snapped, then levered itself off the bank and eased into the black waters, making a little wake as it curled away.

“Some old business,” said the Hald, “has surfaced again. I’m beginning to think it never left at all. We’ve been very careless in yielding to Eldest’s wishes in this ease. I’m less and less convinced it’s a matter of whim with her.”

“The Meth-maren?” Ren-barant frowned and shook his head. “Not so easy to do it now. She’s completely random, a nuisance. If it were really worth the risk—”

The Hald looked at him sharply. “Random. So what happened on Meron?”

“A personal quarrel, left over from the first attempt. Gen and Hal have become a cause with the Ilits. It was unfortunate.”

“And on Kalind.”

“Hive-matter, but she wasn’t in it. Blues have settled again. Reds seem to be content enough.”

“Yes. The Meth-maren’s gone. Meron’s damaged and Kalind isn’t unscathed. Attention rests where it doesn’t suit us. The old hive-master’s talent… Arl, we have an enemy. A very dangerous one.”

“She hardly made a secret of her going to Istra. Why make so much commotion of it, if she’s not as mad as we’ve reckoned? A private ship could have reached there in a direct jump. She could have had time to work…”

“The whole Council noticed, didn’t they? It was bizarre enough that it caught the curiosity of the whole Council. Attention focused where we don’t need it focused at all.”

Ren-barant’s face was stark, his arms tightly clenched. “Cold sane, you think.”

“As you and I are. As Moth is. I have news, Art. There was a majat on that liner when it left Kalind. We haven’t discovered yet how far it went, whether all the way with her or whether it got off earlier.”

“Blue messenger?”

“We don’t know yet. Blue or green is a good bet.”

Ren-barant swore. “Thon was supposed to have that cut off.”

“Majat paid the passage,” the Hald said. “Betas can’t tell them apart. The Meth-maren boarded at the last moment…special shuttle, a great deal of noise about it. We knew about her very quickly. Use of her credit was obvious, at least the size of the transaction and the recipient, which was Andra Lines, through one of their sub-agents. But the majat paid in jewels, cash transaction, freighted up dormant and inconspicuous…a special payment to someone, I’ll warrant. Cash. No direct record to our banks. No tracing. We still can’t be sure how much was actually paid: probably a great deal went into the left hand while the right was making records; but the Meth-maren was right there, using vast amounts of credit, very visible. We didn’t find out about the majat until our agents started asking questions among departing passengers. Betas won’t volunteer that kind of gossip. But the whole operation, that a hive could bypass our surveillance and do it so completely, so long—”

“The Thons do nothing. Maybe we’d better ask some questions about the quality of that support.”

“She’s Meth-maren; the Then hive-masters have no influence with the blues. And Council can vote Thon the post; they can’t make them competent in it. Anyone can handle reds. The test is whether Thon can control the blues. I think Thon is beyond the level of their competency, for all their assurances to us. The Meth-maren’s running escort for majat; she outwitted Thon, and she’s made Council look toward Istra. The old woman, Arl, the old woman is collecting statistics; she’s taking interest again; there’s a chance she’s taken interest for longer than we’ve known.”

The Ren-barant hissed softly between his teeth.

“There’s more,” the Hald said. “The old woman dropped a word about the Meth-maren being– useful. Useful. And that with her sudden preoccupation with statistics. Istran statistics, The Pedra bill is coming up. We’d better be ready, before the old woman hits us with a public surprise. Istra’s vulnerable.”

“Someone had better get out there, then.”

“I’ve moved on that days ago.” And at the Ren-barant’s sudden, apprehensive stare. “ Thatmatter is on its way to being solved. It’s not the Meth-maren I’m talking about.”

“Yes,” the Ren-barant said after a moment. “I can see that”

“Tand’s next to her. He stays, no breath of doubt near him. The organisation has to be firmed up, made ready on the instant. You know the program. You know the contacts. I put it on you. I daren’t. I’ve gone as far as I can.”

The Ren-barant nodded grimly. They began to part company. Suddenly the Ren-barant stopped in his tracks and looked back. “There’s more than one way for Moth to use the Meth-maren. To provoke enemies into following the wrong lead.”

Ros Hald stared at him, finally nodded. It was the kind of convolution of which Moth had long proved capable. “We’ve counted on time to take care of our problems. That’s been a very serious mistake. Both of them have to be cared for—simultaneously.”

The mudsnake surfaced again, hopeful. The Hald tossed it the rest of the morsel: sullen jaws snapped. It waited for more. None came. It slipped away again under the black waters and rippled away.

ii

The Istran shuttle was an appalling relic. There was little enough concession to comfort in the station, but there was less in the tight confines of the vessel which would take them down to surface. Only the upholstery was new, a token attempt at renovation. Raen surveyed the machinery with some curiosity, glanced critically into the cockpit, where pilot and co-pilot were checking charts and bickering.

The Istrans had settled in, all nine of them, Merek Eln and Parn Kest, the several business types and their azi guard. Warrior had taken up position in the rear of the aisle, the only space sufficient for its comfort and that of the betas. It closed both chelae about tire braces of the rearmost seats, quite secure, and froze into the statue-like patience of its kind.

Jim came up the ramp, and after some little perplexity, secured the whole carrier into storage behind the Eln-Kest’s modest luggage…forced tire door closed. Raen let him take his seat first, next the sealed viewport, then settled in after, opposite Merck Eln, and fastened the belts. Her pulse raced, considering the company they kept and the museum-piece in which they were about to hurtle into atmosphere.

“This is quite remarkable,” she said to Jim, thinking that Meron in all its decadent and hazardous entertainments had never offered anything quite like Istran transport.

Jim looked less elated with the experience, but his eyes flickered with interest over all the strangeness…not fear, but a feverish intensity, as if he were attempting to absorb everything at once and deal with it. His hands trembled so when he adjusted his belts that be had trouble joining them.

The co-pilot stopped the argument with the pilot long enough to come back and check the door seal, went forward again. The pilot gave warning. The vessel disengaged from its lock and went through the stomach-wrenching sequence of intermittent weightlessness and reorientation under power as they threaded their way out of their berth. The noise, unbaffled was incredible.

“Kontrin,” Merek Eln shouted, leaning in his seat.

“Explanations?” Raen asked.

“We are very grateful—”

“Please. Just the explanation.”

Merek Eln swallowed heavily. They were in complete weightlessness, their slight wallowing swiftly corrected. The noise died away save for the circulation fans. Istra showed crescent-shaped on the forward screen, more than filling it; the station showed on the aft screen. They were falling into the world’s night side, as Raen judged it.

“We are very glad you decided to accept transport with us,” Eln said. “We are quite concerned for your safety at Istra, onstation and onworld. There’s been some difficulty, some disturbance. Perhaps you have heard.”

Raen shrugged. There were rumours of unrest, here and elsewhere, of crises; of things more serious…she earnestly wished she knew.

“You were,” Merek On said, “perhaps sent here for that reason.”

She made a slight gesture of the eves back toward Warrior. “You might ask it concerning its motives.”

That struck a moment of silence.

“Kontrin,” said sera Kest, leaning forward from the seat behind. “For whatever reasons you’ve come here—you must realise there’s a hazard. The station is too wide, too difficult to monitor. In Newhope, on Istra, at least we can provide you security.”

“Sera—are we being abducted?”

The faces about her were suddenly stark with apprehension.

“Kontrin,” said Merek Eln, “you are being humorous; we wish we could persuade you to consider seriously what hazards are possible here.”

“Ser, sera, so long as you persist in trying to tell me only fragments of the situation, I see no reason to take a serious tone with you. You’ve been out to Meron. You’re coming home. Your domestic problems are evidently serious and violent, but your manner indicates to me that you would much rather I were not here.”

There was a considerable space of silence. Fear was thick in the air.

“There has been some violence,” said one of the others. “The station is particularly vulnerable to sabotage and such acts. We fear it. We have sent appeals. None were answered.”

“The Family ignored them. Is that your meaning?”

“Yes,” said another after a moment.

“That is remarkable, seri. And what agency do you suspect to be the source of your difficulty?”

No one answered.

“Dare I guess,” said Raen, “that you suspect that the source of your troubles isthe Family?”

There was yet no answer, only the evidence of perspiration on beta faces.

“Or the hives?”

No one moved. Not an eye blinked.

“You would not be advised to take any action against me, seri. The Family is not monolithic. Quite the contrary. Be reassured: I am ignorant; you can try to deceive me. What brought the two of you to Meron?”

“We—have loans outstanding from MIMAK there. We hoped for some material assistance…”

“We hoped,” Parn Kest interrupted brusquely, “to establish innerworlds contacts—to help us past this wall of silence. We need relief…in taxes, in trade; we were ignored, appeal after appeal. And we hoped to work out a temporary agreement with MIMAK, against the hope of some relief. Grain. Grain and food. Kontrin—we’re supporting farms and estates which can’t possibly make profit. We’re at a crisis. We were given license for increase in population, our own and azi, and the figures doubled our own. We thought future adjustment would take care of that. But the crisis is on us, and no one listens. Majat absorb some of the excess. That market is all that keeps us from economic collapse. But food…food for all that population… And the day we can’t feed the hives… Kont’ Raen, agriculture and azi are our livelihood. Newhope and Newport and the station…and the majat…derive their food from the estates; but it’s consumed by the azi who work them. There are workers enough to cover the estates’ needs four times over. There’s panic out there. The estates are armed camps.”

“We were told when we came in,” Eln said in a faint voice, “that ITAK has been able to confiscate azi of some of the smaller estates. But there’s no way to take them by force from the larger. We can’t legally dispose of those contracts, by sale or by termination. There has to be Kontrin—”

“—license for transfer or adjustment,” Raen finished. “Or for termination without medical cause. I know our policies rather thoroughly, ser Eln.”

“And therefore you can’t export and you can’t terminate.”

“Or feed them indefinitely, Kontrin. Or feed them. The economics of the farms insist on a certain number of azi to the allotted land area. Someone… erred.”

Eln’s lips trembled, having said so. It was for a beta, great daring.

“And the occasion for violence against the station?”

“It hasn’t happened yet,” one of the others said.

“But you fear that it will. Why?”

“The corporations are blamed for the situation on the estates. Estate-owners are hardly able to comprehend any other—at fault.”

There was another silence, deep and long.

“You’ll be glad to know, seri, that there are means to get a message off this world, one that would be heard on Cerdin. I might do it. But there are solutions short of that. Perhaps better ones.” She thought then of Jim, and laid a hand on his knee, leaning toward him. “You are hearing things which aren’t for retelling…to anyone.”

“I will not,” he said, and she believed him, for he looked as if he earnestly wanted to be deaf to this. She turned back to Eln and Kest.

“What measures,” she asked them, “ havethe corporations taken?”

No one wanted to meet her eyes, not those two, nor their companions.

“Is there starvation?” she asked.

“We are importing,” one of the others said at last, a small, flat voice.

Raen looked at him, slowly took his meaning. “Standard channels of trade?”

“All according to license. Foodstuffs are one of the permitted—”

“I know the regulations. You’re getting your grain from Outside trade. Outsiders.”

“We’ve held off rationing. We’ve kept the peace. We’re able to feed everyone.”

“We’ve tried to find other alternatives.” Merek Eln said. “We can’t find surplus anywhere within the Reach. We can’t get it from Inside. We’ve tried, Kont’ Raen.”

“Your trip to Meron.”

“Part of it, yes. That. A failure.”

“Ser Eln, there’s one obvious question. If you’re buying Outsider grain…what do you use to pay for it?”

It was a question perhaps rash to ask, on a beta vessel, surrounded by them, in descent to a wholly beta world.

“Majat,” one of the others said hoarsely, with a nervous shift of the eyes in Warrior’s direction. “Majat jewels. Softwares.”

“Kontrin-directed?”

“We—pad out what the Cerdin labs send. Add to the shipments.”

“Kontrin-directed?”

“Our own doing,” the man beside him said. “Kontrin, it’s not forbidden. Other hive-worlds do it.”

“I know it’s legal; don’t cite me regulations.”

“We appealed for help. We still abide by the law. We would do nothing that’s not according to the law.”

According to the law…and disruptive of the entire trade balance if done on a large scale: the value of the jewels and the other majat goods was upheld by deliberate scarcity.

“You’re giving majat goods to Outsiders to feed a world,” Raen said softly. “And what do majat get? Grain? Azi? You have that arrangement with them?”

“Our population,” sera Kest said faintly, “even now is not large—compared to inner worlds. It’s only large for our capacity to produce. Our trade is azi. We hope for Kontrin understanding. For licenses to export.”

“And the hives assist you in this crisis—sufficient to feed all the excess of your own population, and the excess of azi, and themselves. Your prices to the majat for grain and azi must be exorbitant, sera Kest.”

“They—need the grain. They don’t object.”

“Do you know,” Raen said, ever so softly, “I somehow believe you, sera Kest.”

There was a sudden stomach-wrenching shift as the shuttle powered into entry alignment. They were downward bound now, and the majat moved, boomed a protest at this unaccustomed sensation; then it froze again, to the relief of the betas and the guard azi.

“We’re doing an unusual entry,” Raen observed, feeling the angle.

“We don’t cross the High Range. Fad weather.”

She looked at the beta who had said that, and for that moment her pulse quickened—a sense that, indeed, she had to accept their truths for the time. She said nothing more, scanning faces.

They were coming in still nightside, at a steeper angle than was going to be comfortable for any reason. There might be quite a bit of buffeting. Jim, unaccustomed to landings even of the best kind, was already looking grey. So were the Eln-Kests.

Two corporations: ITAK onworld and ISPAK, the station and power corporation overhead. ISPAK was a Kontrin agency, that should be in direct link with Cerdin. So were all stations. They were too sensitive, holding all a world’s licensed defense; and in any situation of contest, ISPAK could shut Istra down, depriving it of power. With any choice for a base of operations, ITAK onworld was not the best one, not unless the stakes were about to go very high indeed.

No licenses, no answer to appeals: the fink to Cerdin should have had an answer through their own station. No relief from taxes; other worlds had such adjustments, in the presence of Kontrin. Universal credit was skimmed directly off the tax; majat were covered after the same fashion as Kontrin when they dealt through Kontrin credit; but they could, because they were producers of goods, trade directly in cash, which Kontrin in effect could not. Throughout the system, through the network of stations and intercomp, the constant-transmission arteries which linked all the Reach, there were complex-formulae of adjustment and licensing, the whole system held in exact and delicate balance. A world could not function without that continual flow of information through station, to Cerdin.

Only Istra was supporting a burden it could not bear, while inner worlds as well were swollen with increased populations, with no agricultural surpluses anywhere to be had. Council turned a deaf ear to protests, after readjusting population on a world where arable land was scarce.

And the azi-cycle from lab to contract was eighteen years, less for majat-sale.

Nineteen years, and Council had closed its eyes, deafened itself to protests, talked vaguely about new industry. Population pressure was allowed to build, after seven hundred years of licensed precision, every force in meticulous balance.

She watched the screen for a time, the back of her right hand to her lips, the chitin rough against them.

Blue-hive, blue-hive messenger, hives in direct trade with betas—and a world drowning in azi, as all the Reach was beginning to feel tire pressure—a forecast for other worlds, while Council turned a deaf ear to cries for help.

Moth still ruled. That had to be true, that Moth still dominated Council. The Reach would have quaked at Moth’s demise.

What ARE you doing?she wondered toward Moth.

And put on a smile like putting on a new garment…and looked toward set On and sera Kest, enjoying their unease at that shift of mood. “I seem to recall that you invited me to be your guest. Suppose that I accept.”

“You are welcome,” Kest said hoarsely.

“I shall take the spirit of your hospitality…but not as a free gift. My tastes can be very extravagant. I shall pay my own charges. I should expect no private person to bear with me, no private person nor even ITAK. Please permit this.”

“You are very kind,” said ser Eln, looking vastly relieved. They began to feel their descent. The shuttle, in atmosphere, rode like something wounded, and the engines struggled to slow them, cutting in with jolting bursts. Eventually they reached a reasonable airspeed, and the port shields went back. It was pitch black outside, and lightning flared. They bit turbulence which dampened even Raen’s enthusiasm for the uncommon, and dropped through, amazingly close to the ground.

A landing-field glowed, blue-lit, and abruptly they were on it, jolting down to a halt on great blasts of the engines.

They were down, undamaged, moving ponderously up to the terminal, a long on-ground process. Raen looked at Jim, who slowly unclenched his fingers from the armrests and drew an extended breath. She grinned at him, and he looked happier, the while the shuttle rocked over the uneven surface. “Luggage,” she said softly. “You might as well see to it. And when we’re among others, don’t for the life of you let some. one at it unwatched.”

He nodded and scrambled up past her, while one of the guard azi began to see to the Eln-Kests’ baggage.

The shuttle pulled finally up to their land berth, and met the exit tube. The pilot and co-pilot, their dispute evidently resolved, left controls and unlatched the exit.

Raen arose, finding the others waiting for her, and glanced back at Warrior, who remained immobile. Cold air flooded in from the exit, and Warrior turned its head hopefully.

“Go first,” Raen bade the Istran seri and their azi. They did so in some haste; and Jim pulled the luggage carrier out after the ITAK azi. Raen lifted her right hand and beckoned Warrior to follow her out; the shin’s officers scrambled back into the cockpit and hastily closed their door.

The party began to sort themselves into order in the exit tube, the ITAK folk and their armed azi keeping ahead. Raen walked with Jim and Warrior, whose strides were apparent slow motion beside those of humans.

Customs officials were waiting at the end: incredibly, they only stared stupidly at Warrior still coming and proceeded to hold up the ITAK men, stopping the whole party, with Warrior fretting and humming distress. The Eln-Kests and the others began at once producing cards for the agents, who bore ISPAK badges.

It was bizarre. Raen stared at the uniformed officials for the space of a breath, then thrust her way to them, motioned for the Eln-Kests to move on. There were stunned looks from the officials, even outrage. She made a fist of her right hand and held that in their view.

There was no recognition for an instant: a Kontrin wearing House Colour, and a majat Warrior, and these betas simply stared. Of a sudden they began to yield, melted aside, vying for obscurity, “Move!” Raen said to the others, ordering azi, betas and majat with equal rudeness; her nerves were taut-strung; public places were never to her liking, and the dullness of these folk bewildered her.

They entered the concourse, a place surprisingly trafficked… AIRPORT, a sign advised, pointing elsewhere, which might explain some of the traffic; a, sign advised of a scheduled flight to Newport weekly, and a beard displayed scheduled flights to Upcoast, but few walkers had any luggage. It was the stores, Raen decided, the shopping facilities, which sight be the major ones for the beta City here. Everywhere the ITAK emblem was prominently displayed, the letters encircled; under-corporations advertising goods and, services and setting from small sample-shops all bore the ITAK symbol somewhere on their signs. The faint aroma from restaurants, their busy tables, gave no hint of a world on the brink of rationing and starvation. The goods were on a par with Andra, and nothing indicated scarcity.

Betas, crowds of betas, and nowhere did panic start in that horde. Adults and rare children stared at them and at Warrior…stared long and hard, it might be, but there was no panic at such presence. It was insane, that on this world a majat Warrior could be so ignored; or a Kontrin, evident by Colour.

They were not sure, she thought suddenly. Downworlders. No one of them had seena Kontrin. They perhaps suspected, but they did not expect, and they were not in a position, these short-lived betas, to recognise a Colour banned in inner-worlds for two decades. It was even possible that they did not know the Houses by name; they had no reason to: no beta of Istra had to deal with them.

But a majat needed no recognition. Betas elsewhere had died in panic, trampling each other…until majat in the streets became ordinary. She had heard that this had happened in places she had left.

Her nape-hairs prickled with an uncommon sense of a whole world amiss. She scanned the displays they passed, the garish advertising that denied economic doom, but most of all she regarded the crowds, free-walking and those standing by counters who turned to look at them.

The hands, the hands: that was her continual worry. And she could not see behind her.

“I read blue-hive,” Warrior intoned suddenly. “I must contact.”

“Where?” Raen asked. “Explain. Where are you looking? Is there a heat-sign?”

It stopped, froze. Mandibles suddenly worked with frenzied rapidity, and auditory palps swept back, deafening it, like a human stopping his ears. Raen whirled to the fix of its gaze, heard a solitary human shriek taken up by others.

Warriors.

They poured forward out of an intersecting corridor, a dozen of them, almost on them, and the sound they shrilled entered human range, agony to the cars. Blue Warrior moved, scuttled for a counter, and the attackers pursued with blinding speed, more pouring out from another hall, overturning displays of clothing. Men screamed, dashed to the floor by the rash, trying to escape the shop.

Raen had her gun in hand…did not even recall drawing; and put a shot where it counted, into the neural complex of the leading Warrior, whirled and took another. She stumbled in her retreat, hit a solid wall, stood there braced and firing.

Reds. Hate improved her aim. Her mind was utterly cold. Three went down, and others swarmed the counter where betas and Warrior scattered in panic. She fired into the attackers and swung left, following Warrior’s darting form, into several reds. She took out one, another. Warrior leaped on the third and rolled with it in a tangle of limbs, a squalling of resonance chambers. Raen caught movement out of the tail of her eye and whirled and fired, no longer alone: the azi guards had decided to back her. Betas had lifted no hand against majat, dared not, by their psych-set; but humans were dead out on the floor. One body was almost decapitated by insist jaws. Blood slicked the polished flooring in great smears where insist feet had slipped. Other humans were bitten.

Surviving reds tried to Group; her fire prevented it. She saw other insist crowded in the corner down at the turning, Grouped and thinking. Not reds; they would have come into it. The reds which survived were confused. Azi fire crippled them; Raen sighted with better knowledge of anatomy and finished the job. Blue Warrior was up, excited.

Then came the flare of a weapon from the farther group, several of them. Warrior went down, limbs threshing, air droning from resonance chambers.

“Stop them!” Raen shouted at the azi. The insist charged, ran into their concentrated fire: five, six, seven of them downed One scuttled off, slipping on the floor, a limb damaged. Two shielded that retreat with their own bodies. They were the sacrifices. Raen took one. The azi butchered the other with their fire.

They were alone, then. Humans lay tangled with dead majat. She looked about her, at majat still convulsing in death-throes: those would go on for some minutes…there was no intelligence behind it. Merek Eln and Parn Kest were down, along with their companions from ITAK, and one of the guard azi. Bystanders were dead. A siren began to sound. It was already too late for the victims of bite: they had long since stopped breathing.

Blue Warrior still moved. She left the wall and the two living azi guards and went out into the center of the bloody floor, where Warrior lay, in a seeping of clear majat fluids. She held out her hand and it knew her.

Air sucked into the chambers. Auditory palps extended, trembling.

“Taste,” it begged of her.

“Reds didn’t get it,” she said. “We took them all.”

“Yesss.”

Someone cried out, down the corridor. More tall shapes had entered, moving in haste: she flung up her hand, forbidding the azi to fire.

“Blues have come,” she said. Warrior attempted to rise, but had no control of its limbs. She gave it room, and the blues scattered human medical personnel and what security forces had arrived. They crossed the last interval cautiously, stiff and sidling, until Raen showed her right hand, and they recognised her for blue-hive Kontrin.