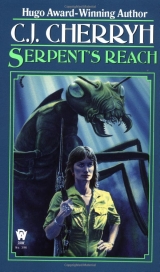

Текст книги "Serpent's Reach"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“It’s too dark, sera,” Merry said. “Papers say twenty-nine, but the mark’s bright.”

The man’s eyes shifted back to Raen, a face rigid with terror.

Such things had been done…a beta highly bribed, Promised protection. “I’d believe a fluke of the dye,” Raen said softly. “But not an azi who’d break and run. Who sent you?”

He gave no answer, but wrenched to free himself.

“Not an assassin,” Raen said, though the hate in that face gave her pause to think so. “Betas don’t go for that. Or—” she added, for the expression was nigh to madness, “maybe not beta at all. Are you?”

“He’s little,” Merry said, “for guard-type.”

That was so too.

A smile took her, sudden surety. “Outsider. One of Tallen’s folk.”

It hit to the mark. The pale eyes shifted from hers.

“O man,” she said softly. “To go to that extent…or did you know what you were getting into when you set that mark on yourself?”

There was no more resistance, none. In that moment she felt a touch of pity, seeing the young Outsider’s desperation. Twenty-nine. He did not look that.

“What’s your name?” she asked him.

“Tom Mundy.”

“You areTallen’s. Easier with him, Max. I doubt he’s here to do murder. I rather well think he realises he’s made a mistake. And I wonder if we haven’t swept up something utterly by chance. Haven’t we, Tom Mundy?”

“Let me go.”

“Let him go, Max. But,” she added at once as the young Outsider braced himself for escape, “you’ll not make it across the City like that, Tom Mundy.”

He looked as if he were on the brink of madness. Some shred of sense held him to listen.

“I’ll sendyou to Tallen,” she said, “without asking you a thing. But if you’d like a drink and a place to sit down, while my people finish checking things out, it would be more convenient for us.”

“Outsider-human,” Warrior murmured in mingled tones.

The Outsider began to weep, tears running down his face; and would have sat down where he was, but that Jim and Merry took him in hand and led him up to the porch, to the door.

iv

There was at least for the time, quiet in the house—stirrings in the back, noises in the basement, but nothing visible in the main room.

And the azi who had been Tom Mundy sat on the couch clutching a drink in his hands and staring at the floor.

“I would like,” Raen said softly, “one simple question answered, if you would.” Jim was by her, and she indicated a place by her; Jim sat down, settled back with a disapproving look.

Mundy slowly lifted his head, apprehension on his face.

“How,” Raen asked, “did you find yourself in such circumstances? Did you come to spy on me? Or did someone put you there?”

He said nothing.

“All right,” she said. “I won’t insist. But I’m guessing it looked like a means for information. And you made a mistake. A real azi number, real papers, guard-status: a spy could pick up a great deal of information that way, and no one would shut an azi away from communications equipment. I’d guess you make regular reports to Tallen, because no one would suspect you’d do such a thing. But it went wrong, I’m guessing.”

He swallowed heavily. “You said that I could go.”

“The car’s being brought. Max and one of the others will deliver you to Tallen’s doorstep—a surprise to him, perhaps. How long were you in those pits?”

“I don’t know,” he said hoarsely. “I don’t know.”

“You didn’t plan coming here, then.” She read the man’s apprehensions and leaned back, shrugged off the question. “You’ll get to Tallen alive, don’t fear that. You’ll come to no harm. How long have you been working on this world?”

Again an avoidance of her eyes.

“There are more of you,” she said. “Aren’t there?”

She obtained a distraught stare.

“Probably,” she said, “I’ve bought more than one of you and haven’t detected it. I own every guard-azi contract available on this continent. I’d sort you out if I could. You’ve been standing guard in ITAK establishments, gathering information, passing it along to Tallen. Of no possible concern to me. Actually I favor the enterprise. That’s why I’m making a present of you to him. I’d advise you, though, if you know of others in that group, you tell me. There are others, aren’t there?”

He took a drink, said nothing.

“Did you know what you were getting into?”

He wiped at his face and leaned his head on his hand, answer enough.

“Tell Tallen,” she said, “I’ll pull his men out if he’ll give me the necessary numbers. I doubt you know them.”

“I don’t,” he said.

“How did you end up in the Registry?”

“Took—took the place of an azi the majat killed. Tattoo…papers…a transport guard. Then the depots shut down. Company stopped operating. Been there—been there—”

“A long time.”

He nodded.

A born-man, subjected to tapes and isolation. She regarded him pityingly. “And of course Tallen couldn’t buy you out. An Outsider couldn’t. Even knowing the numbers, he couldn’t retrieve you. Did anyone think of that, before you let that number be tattooed on?”

“It was thought of.”

“Do you fear us that much?” she asked softly. He avoided her eyes. “You do well to,” she said, answering her own question. “And you know us. You’ve seen. You’ve been there. Bear your report, Tom Mundy. You’ll do well never to appear again in the Reach. If not for the strict quotas of export, you might have been—”

Her heart skipped a beat. She laughed aloud, and Tom Mundy looked at her in terror.

“Azi,” she laughed. “Istra’s primary export. Shipped everywhere.” And then with apprehension, she looked on Jim.

“I am azi,” Jim said, his own calm slightly ruffled. “Sera, I amazi.”

She laid a hand on his arm. “There’s no doubt. There’s no doubt, Jim.” There was the sound of a motor at the door. “That will be the car. Come along, ser Mundy.”

Tom Mundy put the drink aside, preceded her to the door in evident anxiety. She followed out under the portico, where Max had the car waiting, Max standing by it.

“Max, seize him,” Raen said.

Mundy sprang to escape; Max was as quick as the order, and fetched him up against the car, rolled with him to the pavement. Majat were at hand, Warriors. Jim himself made to interfere, but Raen put out a hand, restraining him.

Mundy struggled and cursed. Max shouted for human help, and several more azi arrived on the run.

It needed a struggle. “Don’t harm him,” Raen called out, when it began to look as if that would be the case; Mundy fought like a man demented, and it took a number of azi to put him down. Cords were searched up, all with a great deal of confusion. A shooting, Raen decided, watching the process, would have been far simpler; as it was the police at the gate wanted to intrude: she saw their lights down the drive, but the gate would keep them out, and she reckoned they would fret, but they would not dare climb a wall to investigate.

Mundy was held, finally, hands bound. He cursed and screamed until he was breathless, and lay heaving on the pavement. Max and another gathered him to his feet, and Raen stepped back as he spat at her.

“I’ll keep my word,” she said, “eventually. Don’t try me, Tom Mundy. The worst thing I could do is send you back. Isn’t it?”

He stopped fighting then.

“How long have you been infiltrating?” she asked. “How many years?”

“I don’t know. Would it make sense I’d know? I don’t.”

“Keep him under guard, Max. Don’t take your eyes off him. one of the basement storerooms ought to be adequate. He won’t wantloose down there. Constant watch. See to it.”

They drew him into the house, and through it. Raen lingered, looked at the disturbed Warriors, whose mandibles clicked with nervousness. “Wrong-hive,” she explained in terms they would understand. “Not enemy, not friend, wrong hive. We will isolate that unit. Pass this information. Warrior must guard that-unit.”

They spent a moment analysing those concepts, which were alien to the hive. A stranger should be ejected, not detained.

“That-unit will report if it escapes. We will let it go when it’s good that it report.”

“Yesss,” they said together, comprehending, and themselves filed into the house, nightmare shapes in the Eln-Kests’ hallway.

She started to go in, realised Jim was not with her, and turned back, saw him standing by the car, saw the blank horror on his face. She came back, took his hand. From inside the house came a scream of hysteria. She slipped her hand up to Jim’s elbow; decided to walk round the long way, beneath the portico, past the corner, within the walkway to the back, where there was quiet.

“I amazi,” Jim said.

She pressed his arm the more tightly. “I know so. I know so, Jim. Don’t distress yourself. It’s been a long, hard day.”

She felt the tremor, wordless upset.

“The fall of the dice,” she said, “was a fortunate thing for me. But what a place you’ve come to.”

“I am azi.”

“You do very well at it.”

She walked with him out the arch into the back garden, into chaos, where guard-azi tried to set their supplies in order, where nervous Warriors stalked among humans and touched one and the other. It was pitiful that the azi did not object, that they simply stopped and endured, as no betas would have done, although they were surely afraid. Raen moved among them, sorted Warriors away from humans, nodded to Merry, who began hastily to motion his men into the shelter of the azi quarters. There was no hesitation among them.

The doors closed. Thereafter majat ruled in the garden, and majat azi scampered out the back door, naked, having shed their sun-protections, with their mad eyes and their cheerful grins, their ready acceptance of the touches of Workers and Warriors. They had come to help, and plunged quite happily into the excavations underway in the garden.

“They’ll want feeding,” Raen said. “They’re our responsibility. Jim, go locate the domestics. Have them cook up enough for the whole lot. The majat azi will prefer boiled grain. There look to be about fifty of them.”

Jim murmured agreement, and went, tired and shaken as he was. She watched him at the azi quarters gather up the six in question, watched him shepherd them across to the house, fending away the persistent majat azi. He managed. He managed well. She was able, for a moment, to relax…lingered, gazing on the shadow-forms of majat, the blue lights of the azi winking eerily in the shadowed places of the garden, where the tunnel was deepening.

“Worker,” she said when one passed near her, “how far will the tunnel go?”

“Blue-hive,” it said, which was answer, not inanity. A chill went over her skin. She surmised suddenly that there were tunnels begun elsewhere, an arm of the hive reached out into the city.

Mother accepted; Mother had ordered. The hive reached out to embrace them and protect. She wrapped her arms about her, found the lights shimmering in her vision.

There was a freshness in the air, of moisture and evening. A little drop fell on her arm and she looked up, at a sky mostly clouded. There was another rain coming. It would hardly trouble the majat, or their azi.

She wandered inside finally, as domestic azi came out, bearing foodstuffs, hastening for fear of the majat, to the kitchens in the azi quarters.

One remained in the house kitchen, under Jim’s direction, preparing a different meal. “Thank you,” Raen said to them both; she could have eaten azi porridge without compunction, so tired she was; but she was glad when a good dinner was set before her and Jim took his place at the end of the table.

The hive was about her. The song began. She could hear it in the house, illusory and soft as the rainfall, as old dreams.

Then she thought of the basement, and the cup hesitated at her lips; she drank, and began reckoning of other things.

Of Itavvy, and promises; of Pol Hald; of Tallen.

Of the Family.

There were messages upon messages. Comp spat them out in inane profusion; and she sat and searched them, the while thunder rumbled overhead.

One was ser Dain. MY HUMBLEST APOLOGIES. THE ARTIST IS SER TOL ERRIN, 1028D UPCOAST. There was more, mostly babble. She rubbed her eyes, took a sip of coffee, and entered worldcomp to pull a citizen number, to link it with another program.

One was Pol Hald. NEWPORT IS DISMAL. MY SUFFERING IS EXTREME. REJOICE.

She drank more coffee, sinking into the rhythms of the majat song which ran through the house, nerved herself for intercomp. The dataflow never stopped, world to station, station to station, station to world, jumping information like ships from point to point. Data launched could not be recalled.

She called up the prepared program regarding contracts, and export quotas, the oft-denied permits.

GRANTED, she entered, to all of them.

In an hour the board would be jammed with queries, chaos, the deadlock broken. Cerdin would not know it for eight days.

She called up the city guest house, and drew a sleepy outsider out of bed. “Call Tallen,” she said, using her own image and direct voice, which she had not used on Istra.

Tallen appeared quickly, his person disordered, his face flushed. “Kont’ Raen,” he said.

“I’ve an azi,” she said, “who knows you. His name is Tom Mundy.”

Tallen started to speak, changed his mind. Whatever of sleep there was about him vanished.

“He’s not harmed,” she said. “Won’t be. But I want to know how long this has been going on, ser Tallen. I want an answer. How much and how many and how far?”

“I’ll meet with you.”

She shook her head. “Just a plain answer, ser. Monitored or not. How far has the net spread itself?”

“I have no desire to discuss this long-distance.”

“Shall I ask Mundy?”

Tallen’s face went stark. “You’ll do as you please, I imagine. The trade mission—”

“Is under Reach law, Kontrin law. I do as I please, yes. He’s safe for the moment. I’ll give him back to you, so you needn’t do anything rash. I merely advise you that you’ve done a very unwise thing, ser. Give me those numbers and I’ll do what I can to sort things out for you; you understand me. I can act where you can’t. I’m willing to do so…a matter of humanity. Give me the numbers”

Tallen broke contact.

She had feared so. She shook her head, swallowed down a stricture in her throat with a mouthful of cooling coffee, finally turned housecomp over to automatic.

She drank the rest of the coffee, grimacing at the taste, followed it with half a measure of liquor, and sat listening to the thunder.

“Sera,” Jim said, startling her. She glanced at the doorway.

“Go to bed,” she told him. “What about the azi downstairs? Settled?”

He nodded.

“Go on,” she said. “Go rest. You’ve done what you can.”

He was not willing to leave; he did so, and she listened as his footsteps went upstairs. She sat still a moment, listening to the hive-song, then rose and went downstairs, into the dark territory of the basement.

Majat-azi gathered about her. She bade them away, suffered with more patience the touch of Workers and Warriors. There was a door guarded by Warriors. She. opened it, and two guard-azi rose to their feet, from the chairs inside. The third huddled in the corner, on a mat of blankets.

“I’ve spoken with Tallen,” she said. “He’s very upset. Is there anything I can get for your comfort?”

A jerk of the head, refusal. He would not look at her face. They had taken the cords off him. There was the double guard to restrain him.

“You were a transport guard. Were you sensible enough to understand that what you’re seeing on this world is not the usual, that things have gone vastly amiss?”

Still he would say nothing, which in his place, was the wiser course.

She sank down, rested her arms across her knees, stared at him. “I’ll hazard a guess, ser 113-489-6798, that all you’ve done has been a failure: that Tallen would have known mehad it succeeded. You’ve scattered azi off this world, if at all, only to have the embargo stall them, if not here, on Pedra, on Jin. And do you know where they’ll be? In cases similar to your own. You entered that faculty when the depots were closed…about half a year ago. What do you think will become of those stalled there for years, as some are—two years already, for some? What do you think will come out of that? You think they’ll be sane? I doubt it. And how many azi have a to transmission of messages via intercomp? None, ser. You’ve thrown men away. Like yourself.”

Eyes fixed on hers, hollow, in a shaven skull. Thin hands clasped knees against his chest. Ire would never, she thought, be the man he would have been. Youth, cast away in such a venture. More than one of them. He might break. Most would, if majat asked the questions. But she much doubted that he knew anything beyond himself.

“Majat,” she said, “killed the azi you replaced. Was that a hazard, running the depots?”

“They’re all over,” he said hoarsely. “Farms—armed camps for fear of them.”

Cold settled on her at that. She nodded. “Ever see them in the open?”

“Once. Far across the fields. We drove out of it, fast as we could.”

“What do you suppose they would do?”

“There’d been trucks lost. They’d find the trucks. Nothing else.”

She nodded slowly. “It fits, ser Mundy. It does fit. Thank You. Rest now. Get some sleep. You’ll not be bothered. And I’ll get you back to Tallen in one piece if you’ll stay in this room. Please don’t try my guards. A scratch from a majat is deadly as a bite. But they won’t come into this room.”

She rose, left, walked out among the Warriors. The door closed behind her. She singled out one of the larger ones, touched it, soothed it. “Warrior, many azi, many, in blue. hive? Weapons?”

“Yes.”

“The hives have taken azi, taken food?”

There was a working of mandibles, a little disturbance at this question. “Take, yesss. Red-hive takes, goldss take, greens take, blue-hive, yessss. Store much, much. Mother says take, keep, prevent other-hives.”

“Warrior, has blue-hive killed humans?”

“No. Take azi. Keep.”

“Many azi.”

“Many,” Warrior agreed.

v

Jim sat on the bed, massaged his temples, tried to still the pounding in his skull. Never panic; never panic. Stop. Think. Thinking Is good service. It is good to serve well.

He seldom recalled the tapes verbatim. The thoughts were simply there, inwoven. This night he remembered, and struggled to remember. He was unbearably tired. Strange sights, everything strange—he trembled with the burden of it.

The other Kontrin had gone, that at least, away around the world; but the majat would not go, nor this flood of azi. He remained unique: he sensed this, clung to it.

He had here, and the others did not. He had this room, this place he shared with her, and the others did not.

He rose finally, and went through all the appropriate actions, born-man motions, for although the Jewelhad rigid rules about cleanliness, there had been no facilities such as these, even in upper decks. He showered, coated himself liberally with soap, once, twice, three times…in sheer enjoyment of the fragrance, so unlike the bitter detergent that had come automatically through the azi-deck system, stinging eyes and noses. He worked very hard at his personal appearance: he understood it for duty to her, to match all these fine things she had, the use of which she gave him; and shewas the measure of all the wide world through which she drew him. He had seen rich men, powerful men, in absolute terror of her; and majat who feared her and majat who obeyed her; and another Kontrin who treated her carefully; and he himself was closest to her, an importance as heady as wine. On the ship he had been terrified by the reaction of others to her; he had not known how it would be to live on the other side of it, shielded within it.

He was inthe house, and others were not. He had seen new things, the details of which were still a muddle to him, most even without words to call them or recall them, without comparisons to which to join them, only some that her tapes had given him. He had been with her in places far more important than even those powerful rich men had been, that society which drifted through the salon of the Jewel, offering snippets of their lives to his confused inspection, a stream dark before and dark after. He had gone out, into that unimaginable width in which born-men lived, and shewas there, so that he was never lost.

He had stood back over the pens, which he had half-forgotten, as all that time before the Jewelwas confused in his memory, hard to touch from the present, for it had been go empty, so void of detail. Today he had looked down, as he had looked down in earlier times, and known that he was not on his way back from exercise, to return again to the pens and the half-world of the tapes breathing through his mind. This time he had come to look, and to walk away again, at herback, until the stink purged itself into clean air and light. There was no fear of that place again, forever.

Sheprevented.

She was there, in the night, in the dark, when his dreams were of being alone, within the wall, and only the white glare of spotlights above the tangled webs of metal, the catwalks…when one huddled in the corner, because the walls were at least some touch, somewhere to put one’s back and feel comforted. On the azi-deck everyone slept close, trying to gain this feeling, and the worst thing was being Out, and no one willing to touch. Being Out had been the most terrible part of the long voyage here, when he had borne the Kontrin like a mark on him, and no one had dared come near him. But she did…and more than that, more even than the few passengers who had engaged him for a night or even a short voyage, several with impulses to generosity and one that he tried never to remember…she stayed. The rich folk had let him touch, had shown him impressions of experiences and luxury and other things forever beyond an azi’s reach; each time he would believe for a while in the existence of such things, in comfort beyond the blind nestlings-together on the azi-deck. Love, they would say; but then the rich folk would go their way, and his contract rested with the ship forever, where the only lasting warmth was that of all azi, whatever one could gain by doing one’s work and going to the mats at night In with everyone, nestled close.

Then there was Raen. There was Raen, who was all these things, and who had his contract, and who was therefore forever.

Warm from the shower he lay down between the cool sheets, and thought of her, and stared at the clouds which flickered lightnings over the dome, at rain, that spotted the dome and fractured the lightnings in runnels.

He had no liking for thunder. He had never had, from the first that he had worked his year in Andra’s fields, before the Jewel. He liked it no better now. Nonsense ran through his head, fragments of deepstudy. He recited them silently, shuddering at the lightnings.

To some eyes, colors are invisible;

To others, the invisible has many colors.

And both are true. And both are not.

And one is false. And neither is.

He squeezed shut his eyes, and saw majat; and the horrid naked azi, the bearers of blue lights; and an azi who was no azi, but a born-man who had gone mad in the pens, listening to azi-tapes. The lights above the pens had never flickered; sounds were rare, and all meaningful.

The lightning flung everything stark white; the thunder followed, deafening. He jumped, and lay still again, his heart pounding. Again it happened. He was ready this time, and did not flinch overmuch. He would not have her to know that he was afraid.

She delayed coming. That disturbed him more than the thunder.

He slept finally, of sheer exhaustion.

He wakened at a noise in the room, that was above the faint humming of the majat. Raen was there; and she did not go to the bath as she had on the nights before, but moved about fully dressed, gathering things quietly together.

“I’m awake,” he said, go that she would not think she had to be quiet.

She came to the bed and sat down, reached for his hand as he sat up, held it. The jewels on the back of hers glittered cold and colourless in the almost-dark. Rain still spattered the dome, gently now, and the lightnings only rarely flickered.

“I’m leaving the house,” she said softly. “A short trip, and back again. You’re safest here on this one.”

“No,” he protested at once, and his heart beat painfully, for nowas not a permitted word. He would have made haste to disengage himself from the sheets, to gather his own belongings as she was gathering hers.

She held his arm firmly and shook her head. “I need you here. You’ve skills necessary to run this house. What would Max do without you to tell him what to do? What would the others do who depend on his orders? You’re not afraid of the majat. You can manage them, better than some Kontrin.”

He was enormously flattered by this, however much he was shaking at the thought. He knew that it was truth, for she said it.

“Where are you going?” he asked.

“A question? You amaze me, Jim.”

“Sera?”

“And you must spoil it in the same breath.” She smoothed his hair from his face, which was a touch infinitely kind, taking away the sting of her disappointment in him. “I daren’t answer your question, understand? But call the Tel estate if you must contact me. Ask comp for Isan Tel. Can you do that?”

He nodded.

“But you do that only in extreme emergency,” she said. “You understand that?”

He nodded. “I’ll help you pack,” he offered.

She did not forbid him that. He gathered himself out of bed, reached for a robe against the chill of the air-conditioning. She turned the lights on, and he wrapped the robe about himself, pushed the hair out of his eyes and sought the single brown case she asked for.

In truth she did not pack much; and that encouraged him, that most of her belongings would remain here, and she would come back for them, for him. He was shivering violently, neatly rearranging the things she threw in haphazardly.

“There’s no reason to be upset,” she said sharply. “There’s no cause. You can manage the house. You can trust Max to keep order outside, and you can manage the inside.”

“Who’s going with you?” he asked, thinking of that suddenly, chilled to think of her alone with new azi, strange azi.

“Merry and a good number of the new guards. They’ll serve. We’re taking Mundy, too. You won’t have to worry about him. We’ll be back before anything can develop.”

He did not like it. He could not say so. He watched her take another, heavier cloak from the closet. She left her blue one. “These azi,” he said, “these– strangeazi—”

“Majat azi.”

“How can I talk to them?” he exclaimed, choked with revulsion at the thought of them.

“They speak. They understand words. They’ll stay with the majat. They aremajat, after a fashion. They’ll fight well if they must. Let the majat deal with their own azi; tell Warrior what you want them to do.”

“I can’t recognise which is which.”

“No matter with majat. Any Warrior is Warrior. Give it taste and talk to it; it’ll respond. You’re not going to freeze on me, are you? You won’t do that.”

He shook his head emphatically.

She clicked her case shut. “The car’s ready downstairs. Go back to bed. I’m sorry. I know you want to go. But it’s as I said: you’re more useful here.”

She darted away.

“ Raen.” He forced the word. Hid face flushed with the effort.

She looked back. He was ashamed of himself. His face was hot and he had no control of his lips and he was sick at his stomach for reasons he could not clearly analyse, only that one felt so when one went against Right.

“A wonder,” she murmured, and came back and kissed him on the mouth. He hardly felt it, the sickness was so great. Then she left, hurrying down the stairs, carrying her own luggage because he had not thought in time to offer. He went after her, down the stairs barefoot…stood useless in the downstairs hall as she hastened out into the rainy dark with a scattering of other azi.

Majat were there, hovering near the car with a great deal of booming and humming to each other. Max was there; Merry was driving. There were vehicles that did not belong to the house, trucks which the other azi boarded, carrying their rifles. Merry turned the car for the gate and the trucks followed.

Max looked at him. He thrust his hands into the pockets of his bathrobe and looked nervously about. “Everything goes on as usual,” he told Max. “Guard the house.” And he went inside then, closed the door after him…saw huge shapes deep in the shadows, the far reaches of the hall, heard sounds below.

He was alone with them. He crossed the hall toward the stairs and one stirred, that could have been a piece of furniture. It clicked at him.

“Be still,” he told it, shuddering. “Keep away!”

It withdrew from him, and he fled up the stairs, darted into the safety of the bedroom.

One had gotten in. He saw the moving shadow, froze as it skittered near him, touched him. “Out!” he cried at it. “Go out!”

It left, clicking nervously. He felt after the light switch, trembling, fearing the dark, the emptiness. The room leapt into stark white and green. He closed the door on the dark of the hall, locked it. There were noises downstairs, scrapings of furniture, and deeper still, at the foundations. He did not want to know what happened there, in that dark, in that place where the strange azi were lodged.

He was human, and they were not.

And yet the same labs had produced them. The tapes…were the difference. He had heard the man Itavvy say so: that in only a matter of days an azi could be diverted from one function to another. A born man put in the pens had come out shattered by the experience.

I am not real, he thought suddenly, as he had never thought in his life. l am only those tapes.

And then he wiped at his eyes, for tears blinded him, and he went into the bath and was sick, protractedly, weeping and vomiting in alternation until he had thrown up all his supper and was too weak to gather himself off the floor.

When he could, when he regained control of his limbs, he bathed repeatedly in disgust, and finally, wrapped in towels, tucked up in a knot in the empty bed, shivering his way through what remained of the night.

vi

The freight-shuttle bulked large on the apron, a dismal half-ovoid on spider legs, glistening with the rain, that puddled and pocked the ill-repaired field and reflected back the floodlights.

There were guards, a station just inside the fence. Raen ordered the car to the very barrier and received the expected challenge. “Open,” she radioed back, curt and sharp. “Kontrin authorisation. And hurry about it.”