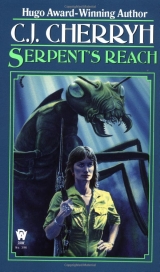

Текст книги "Serpent's Reach"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Jim wiped at his face, crouching by Max’s side among the rocks. Pol was by him: they spared one young azi to keep a gun in Pol’s ribs constantly, for whatever the Kontrin was, he was a born-man and old in such manoeuvrings, able to forewarn them what the hives might do…most of all what the human mind among them might do.

He’s there,Pol had said, when the last assault had nearly carried to them, when cracks had appeared in the wall and fire from the gate had distracted them. That’s Morn behind that. The next thing is to watch our backs.

And that proved true.

“He’s delayed over-long,” Pol said after a time. “I’m surprised. He should have tried by now. That means he and his allies are up to something that takes a little time.”

Jim looked at him. The Kontrin’s accustomed manner was mockery; Pol used little of that in recent hours. His gaunt face was yet more hollowed, his eyes shadowed with the exhaustion which sat on them all. The high heat would come by mid-morning; they wore sunsuits, but neither masks nor visors in place, and the sleeves were all unfastened for comfort. Azi rested in their places, slumped against rocks or walls, seeking what sleep could be gotten, for they had had little in the night. Pol leaned his head back against the rock that sheltered them, eyes shut.

“What would take time?” Max wondered aloud.

“Tunnels,” Jim said, the thought leaping unwanted into his mind. He swallowed heavily and tried to reason around it. “But Warriors don’t dig and Workers don’t fight.”

Pol lifted his head. “Azi do both,” he said, and shifted around to face forward. “Look at the cracks in that wall. They’re wider.”

It was so. Jim bit at his lips, rose and went aside, where one of the Warriors crouched…touched its offered scent-patches.

“Jim. Yess.”

“Warrior, the wall’s cracking over there. Pol Hald thinks there could be digging.”

The great head rotated, body shifted, directed toward the wall. “Human eyess…certain, Jim?”

“I can see it, Warrior. A crack in the shape of a tree, spreading and branching. It gets wider.”

Chelae brushed him; palps flicked over his cheek. “Good, good,” Warrior approved, and scuttled off. It sought and locked jaws with the next, and that one moved off into the house, while Warrior continued, touching jaws with each of the Warriors nearest, who spread in turn to pass the message further.

Jim slid back into position next Max and Pol. “It’s disturbed about it,” he panted. He shivered despite the warmth, suddenly realising that he was terrified. They had fought in the night; he had never fired his gun. Now at the prospect of their shelter breached by daylight he sat trembling.

“Easy,” Pol said, put out a thin hand and closed it on his leg until it hurt. The pain focused things. He looked at the Kontrin, suddenly aware of a vast silence, that the shrilling which had surrounded them had fallen away.

“You’re always with Morn,” Jim said hoarsely, for it did not make sense, the tapes with the behaviour of Pol Hald. “You’re out of his house. You wouldn’t go against him.”

“A long partnership.” The hand did not move, though it was gentler. “In the Family, such are rare.”

Treachery,what he had learned warned him. He stared at the Kontrin, paralysed by the touch he should never have allowed.

“Strange,” Pol said, “that at times you have even her look about you.”

The shrilling erupted again; and a portion of the garden sank away, gaping darkness aboil with earth and majat bodies. Blues sprang, engaged; shots streaked from azi weapons.

The wall went down, collapsed in a cloud of dust: through it came a horde of majat, azi among them.

Jim braced the gun and sighted, tried to pull the trigger. Beside him a body collapsed, limp.

It was Max. A shot had gone through his brain. Jim stared down at him, numb with horror.

The azi on the other side cried warning, sprawled back unconscious. Pol had Max’s rifle and whipped it from a backward blow at his guard to aim it up, putting shots into the majat horde, dropping azi and majat with no distinction.

Jim sighted amid them and pulled the trigger, firing into the oncoming mass, unsure what damage he did, his eyes blurred so that it was impossible to see anything clearly.

The sound swelled in his ears, a horrid chirring that ascended out of range. Majat poured from the house behind them, more Warriors than he had known were there. Majat swarmed from the pit before them and through the breached wall; and came on them like a living wave. Pol fired indiscriminately; he did; more came to replace the fallen, as a wider portion of the wall collapsed, exposing their flank.

“Move back!” Pol shouted at him. “Get your men back!” The Kontrin sprang up low and took a new position.

Jim shouted a half-coherent order and scrambled after, slid in at Pol’s side and started firing again.

Then eerie figures appeared among the majat, like majat in the mold of men, bearing each an insignia on the shoulder.

And one was among them that was clearly a man, in Hald Colour.

“Morn,” Pol said, and stopped firing.

Jim sighted for that target, missed; and fire came back, grazed his arm. Pol seized him, pulled him over as a lacery of fire cut overhead.

Majat voices boomed, and stone cracked. One of the portico pillars came down in the sudden rush of majat from the house, a sea of bodies; and among them ran naked majat-azi and azi in sunsuits brown with mud and blood.

Fire cut both ways. Majat and azi fell dying and were trampled by those behind. And one there was slighter than most, with black hair flying and a gun in a chitined fist. The azi by her died, rolled sprawling.

Jim fought to loose himself, flung himself over and saw Morn in the centre of the yard. Raen was blind to him. “Look out!” he screamed.

“ Morn!” Pol yelled, hurled himself to his feet and fired.

Morn crumpled, the look of startlement still on his face. And startlement was on Raen’s face too, horror as she averted the gun. Pol sank to one knee, swore, and Jim seized at him, but Pol stood without his help, braced, fired a flurry of shots into the armoured invaders, who stood as if paralysed.

Raen did the same, and majat swept past the lines of her men, who hurled accurate fire into the opposing tide, majat meeting body to body, waves that collided and broke upon each other, with shrilling and booming. Heads rolled. Bodies thrashed in convulsions. More of the wall collapsed, and again they were flanked. Jim turned fire in that direction, and saw to his horror the majat sweeping down on them.

Pol’s accurate fire cut into them, shots pelting one after the other, precisely timed.

A body slid in from their rear: Merry, putting shots where they counted; and Raen next, whose fire was, like Pol’s, accurate. The shrilling died away; majat rushed from their rear, narrowly missing them in their blinding rush, and they dropped, tucked for protection.

But Pol did not go on firing. He laid his head against the rock, staring blankly before him. Raen touched him, bent, pressed a gentle touch of her lips to his brow.

“That’s once,” Pol said faintly, and the face lost its life; a shudder went through his limbs, and ceased.

Raen averted her face, looked instead at the wave of majat that was breaking, flooding back toward the walls.

And with a curse she sprang up and ran; Merry followed, and other azi. Jim slipped his hand from Pol’s shoulder and snatched at his rifle to follow, past the cover of the rocks.

A dark body hurtled into him, spurs ripping. He sprawled, went under, body upon body rushing over him, until pain stopped.

x

Agony… Mother existed in it, in each powerful drive of Her legs that drove Her vast weight another half-length. Drones moved, themselves unaccustomed to such exertions, their breathing harsh pipings. Workers danced back and forth, offering nourishment from their jaws, the depleted fluids of their own bodies, feeding Her and the Drones.

Their colours grew strange, the blue mottled light and dark, with here and there a blackness. The sight disturbed Her, and She moaned as She thrust Her way along, following the new tunnel, the making of the Workers.

Mother,the Workers sang, Mother, Mother.

And She led them.

I have made the way,the Warrior-mind reported, one of its units touching at Her. Enemies are retreating. Need of Workers now to move the stones.

Well done,She said, tasting of life fluids and of victory.

Warrior scurried away, staggering in its exhaustion and its haste. Follow this-unit,Warrior gave taste to Workers. Follow, follow me.

xi

“Sera?”

Raen caught herself, caught her breath between the wall and Merry’s solid body. An azi-light swung from her wrist. She blinked clear the subway, the vacant tracks coursed by majat. One of the men offered her a flask. She drank a mouthful; it went the round among them, forlorn humans huddled at the side of the arching tunnel. They panted for breath, lost in the strange sounds, the rush of chitined bodies, of spurred feet. One of them, hurt, slumped in a knot against the wall. Raen reached and touched him, obtained a lifting of the head, an attempt to focus. Another gave him a drink.

They were twelve, only twelve, out of all of them. She swallowed heavily and rested her hand on Merry’s shoulder, breathing in slower and slower gasps.

“City central’s up there,” she said. “Blues have A branch. The reds are probably in E, that goes to the port. Greens… I don’t know. Golds…likely C, due south. They’ll mass in central, under ITAK headquarters”

“Three hives against them,” Merry said faintly. “Sera, the blues can’t do it.”

She slid her hand down, pressed his arm. “I don’t think so either, but there’s no stopping them. We’ve kept them alive this long. Merry, take the men, go back. Go back from here. I’ll not throw the rest of you away.”

“Sera—send them back, not me.”

Other voices protested, faces anxious in the blue glow.

“Any of you who wants to stay back, stay,” she said, and rose up and started to walk again, slung the burden of the riflestrap to her shoulder.

They came. Perhaps it was fear of the majat without her. She thought that it might be. She suspected something else, that she was too rational to believe. She wiped at her face, struck the tears away with no realisation of hurt or grief, only that she was very tired and her eyes watered. The tunnel smelled of majat, like musty paper; and they passed strange sights as they walked, found vehicles frozen on the tracks, wherever they had been when power failed; and terrible sights, the sweet-sour reek of death, where betas had died, some sprawled on the tracks, some in vehicles the glass of which had shattered, dead of majat bite or terror—brushed constantly now by the steady rush of Warriors.

But now there appeared. other types amid the press…blue-hive azi, staggering with exhaustion and mindless with haste; and after them, Workers, fluting shrill, plaintive cries.

“They’re all going,” Merry breathed beside her. “Even the queen will follow. Sera, is it wise to be here at all?”

“No,” she said plainly, “it’s not.”

But she did not stop walking, or hesitate. The Worker-cries became song, that filled her ears, ran through her nerves, and banished thought.

Daylight shafted down ahead, where bodies milled, that vast terminal that was central, zero, with day falling down from skylights. Song came up from that heaving mass, and Warriors within it surged this way and that. Workers added themselves, climbing over the bodies of others.

More, Raen thought, far more than blue-hive alone: all, ail hives, met there.

And majat died there, of weakness and wounds, crushed down. The song numbed. Merry held his ears and cried out soundlessly in the chaos; and Raen pressed hands to her own, all of them seeking the retreat of the walls, any place aside from that flood of bodies which kept coming.

The ground shook, the walls quivered.

A faint far glimmering in jewels and azi-lights, Mother came, struggling forward.

Mother drew breath, heaved forward, breathed again, dazed with pain. Her own limbs, reaching out and shifting again out of view, were mottled now, bright blue and dark. About Her moved insanity, Warriors whose colours had gone mad, whose bodies glowed blue and extremities red, whose midlimbs gold, all mottled with green.

Queens were at hand: She heard Them, others, other-hives. Desperation possessed Her, the instinct certain now of direction. There was nothing else.

She saw Them, in a seething mass of colours, among Warriors and Workers and Drones who had gone mad. One of the queens was red, with darker mottlings: She, fiercest; one gold, tinged with red; one green, with shadings of blue, incipient chaos.

Red queen shifted forward, ominous, and went for green, for the tainted and nearest one, breathing out hate.

Red was the killer, the Warrior-fragment, as green was the Worker-mind.

Mother hesitated, trembling, and saw green die, life-fluids drunk.

Blue,red queen breathed, and the Warriors quivered aide, pressing themselves out of the way in terror.

A second queen was dead. Raen shuddered, the hard grip of her azi about her, putting their own bodies between her and the press, a small knot of humanity, blue-lit. Other azi sheltered with them, naked creatures male and female, trembling and holding their ears against the battering sound. Lighter majat clambered over them, Drones, glittering with living jewels, perhaps adding their own screams to the thunder of the queens.

Merry shivered against her. Raen caught his hand and held it, that crushed bone against bone in hers: likely he had no wit left to know; she had none to care.

The battle raged in ponderous slow-motion, hazy shafts of sunlight enveloping the queens atop the living hill, reflecting jewel-colours. Strength held against strength: then came a darting move.

The third queen died, head severed.

The hill of bodies came undone about the survivor, sweeping over and about Her. Drones streamed through, to gather with other Drones; and Workers with Workers; and Warriors with Warriors, ringed about the living queen. The dead were hauled away. The living circles widened, spread throughout the terminal.

The queen moved, shifted position; so did all the others. She breathed out a note that made the walls shake, and after that was quiet.

A human wept, audible, soft sobs.

Raen leaned against Merry a moment, then gathered herself from him, from all the azi, and rose—walked among the still shapes of majat, Warriors, Workers, with the badges of blue-hive, red-hive, green and gold comingled. The rifle was stiff slung from her shoulder. She realised it, and dropped it echoing to the pavement, for there was no way out but to kill a queen, the last Mother of a world, and that she would not do.

She walked within reach of Her, without weapons in hand, and gazed up into the great jewelled face, the moiré eyes, heard the sough of Her breathing.

It was a gold. The pattern was on Her, for those who could read it.

“Mother,” she said, “I’m Raen a Sul, Meth-maren.”

Air sucked in. “Meth-maren,” She sighed, and the huge head lowered, sought taste.

Raen kissed Her, touched the scent-patches, waited for the vast jaws to close; and they did not.

“Meth-maren,” Mother said. “Kethiuy-queen.”

It was blue queen’s memory.

xii

The sun was unbearable. Jim felt the burn of it before he felt anything more, and struggled to shade his face from it. He was held, and had to think which way to turn; and that meant consciousness.

His hands met spines and hair and chitin. He focused at that, and shoved in horror at the stiffening limbs that lay over him, the intertwined corpses of a majat and an azi.

All about him were corpses, shimmering and running in the tears the sun brought to his eyes. He struggled to pull the visor which hung about his neck up to his eyes, to see—and found nothing living anywhere.

The house was ruined, gaping rubble; and bodies lay thickly over the garden, save in one vast track which led to the broken walls…bodies majat and human, naked and clothed. Insects flitted about him as they settled on the dead; he batted at them, fought with fingers stiffening with sunburn to fasten the sunsuit.

Rock moved, a shifting outside the wall. He gathered up a rifle, staggered in that direction, his senses wavering in and out of focus.

He climbed over the rubble, blinked, saw a shadow on the ground and whirled, whipped the rifle up, but the majat’s leap was faster. The gun went off, torn from his hands. Another was on him, pulling from the other side. Chelae gripped his arm, cutting flesh.

Red: he saw the badge and tried to pull from it; the badge of the second was green. It lowered its head, jaws wide, and the palps brushed his lips, his face.

And it drew back. “Jim,” it intoned.

He lived. The fact numbed him. He ceased to struggle, understanding nothing any longer.

“Meth-maren sendss,” red Warrior said.

“Let me go,” he asked then, his heart lurching a beat. “Let me go, Warrior; I’ll come with you.”

It released him. He clutched his injured arm and followed it, trailed by the green, down into the circle of the street, into the dark entry of the subway, into the deep places of the city, where no lights shone at all. At times he stumbled, blind, and his hands met bodies, yielding ones of majat-azi or the spiny hardness of majat. Chelae urged at him, hastening him, lifting him each time he fell.

Blue lights drifted toward him. At first he shrank from meeting them, not wanting delay, not wanting to be left: but he saw herbearing one of those lights, and he thrust his way free of the Warriors and ran, stumbling, toward her.

She met him, held him off at arm’s length to look at him. “You’re all right,” she said, a question in her impatient manner; but her voice trembled. There was Merry by her, and other faces that he knew.

She hugged him then, and he nearly wept for joy; but she did not know, he thought, the things that he must admit, the knowledge that he had stolen, the thing he had made of himself.

He tried to tell her. “I used all the tapes,” he said, “even the black ones. I didn’t know what else to do.” She touched his face and told him to be quiet, with a shift of her eyes toward Merry and the others.

“It’s ruined back there,” he said then. “Everything’s ruined. Where will we go now?”

“In, for a time. Till the cycle completes itself.” Her hand entwined with his: he felt the jewels rough and warm beneath his fingers. She gestured, walked with assurance the way from which she had come. Warriors walked about them; armed majat-azi followed. “It’s going to be a while before I think of outside, a long while, perhaps. Majat-time.”

“I’ve nineteen years,” he said, anticipating all of them, and well-content.

Her fingers tightened on his.

Soft singing filled the air, the peaceful sound of Workers, with the stirrings and movings of many bodies in the tunnels.

“Hive-song,” she said. “They’ve long lives. A turning of nature, a pulse of the cycle, to merge all colors, to divide again. This-sun,they say now. Home-hive.Against those cycles, my own life is nothing at all. Wait with me.”

There was a ship, he thought, recalling Pol. There were betas who might live, who might serve her. He objected to. these things one by one, and she shook her head, silent.

He asked no more.

xiii

Moth,the voices shouted, Moth, Moth!

Eggs,she thought back at them, and mocked them for what they were.

A different sound came through the speaker, the shrilling of majat voices, the crash of metal and wood.

From the vents came a curious paper-scent. Human voices had ceased long ago.

Moth poured the last of the wine, drank it.

And pushed the button.

BOOK TEN

i

The hatch opened, let in the flood of evening air, the gentle light of the setting sun.

“Stay put,”Tallen heard, “Sir, we’re picking up movement out there.”

“Wouldn’t do to run,” he said into the com unit. “Whatever happens—no response, hear me?”

“Be careful.”

Majat. He heard the ominous chirring, and walked forward, very slowly.

Newhope had stood here. Weeds had taken the ruins. At centre rose a hill, monstrous, where no hill had been. He had seen the pictures smuggled out, heard the reports and memorised them, along with family tales.

And in the long passage of years, in the fading of the Wars, thiswaited, where no Outsider dared trespass, until now.

We were wrong, the one side argued, ever to have relied on them.

But governments rose and fell and rose again, and rumours persisted…that life stirred in the forbidden Reach, that the wealth which had made the Alliance what it had been was there to be had, if any power could contrive to obtain it.

And the hives refused contact.

There were human folk on Istra, farmers, who lived out across the wide plains, who told wild tales and traded occasional jewels and rolls of majat-silk.

Tallen had met with them, these sullen, furtive men, suspicious of any ship that called; and there was warning here, for there were no few ships resting derelict in Istran fields.

Sixty years the contact had lapsed: collapse, chaos, war…worlds breaking from the Alliance in panic, warships forcing them in again, all for the scarcity of certain goods and the widespread rumours of majat breakout.

It was told in Tallen’s family that men and majat had coexisted here, had walked together in city streets, had co-operated one with the other.

It was told somewhere in Alliance files that this was so.

He heard the sound nearer now, and walked warily, stopped at last as a glittering creature rose out of the rocks and brush.

A trembling came on him, a loss of will. Natural,he thought, recalling the tales his grandfather had told, who claimed to have stood close to them. Humans react to them out of deep instinct. One has to overcome that.

They see differently:that too, from old Tallen, and from reports deep in the archives. He spread his hands wide from his sides, making clear to it that he had no weapons.

It came closer. He shut his eyes, for he quite lost big courage to look at it near at hand. He heard its loud breathing, felt the bristly touch of its forelimbs. A shadow fell on his closed eyes; something touched his mouth—he shuddered convulsively at that, and the touch and the shadow drew back.

“Stranger,” it said, a harmony of sounds that joined into a word.

“Friend,” he said, and opened his eyes.

It was still near, the moiré eyes shifted through the spectrum at each minute turn of the head. “Beta human?” it asked him.

ii

A stirring ran through the hive. Raen lifted her head, read it in the voices, the shift of bodies, needing no vision in the dark.

Stranger-human,the message came to her, and that pricked at curiosity, for betas would never come this far: they did their grain-trading far out on the riverside, where they brought their sick, such as majat could heal.

And the azi had gone long ago.

She missed them sorely. The hives did, likewise, mourning them in Drone-songs.

Merry had gone, neither first nor last, a sudden seizure of the heart. And she had wept for that, though Merry would hardly have understood it. l am azi,he had said once, refusing to be otherwise. I would not want to outlive my time.And so, one by one, the others had chosen.

It was strange, now, that a beta would have ventured into majat land, under the great Hill.

“Jim,” she said.

“I hear.” He found her hand, needing sight no more than she, as he was in other ways skilled with her skills.

Of all of them, Jim remained, a costly gift of Worker lives, and of his own will, more than Merry had had, who had wanted things his own way, in old patterns, in terms he understood.

For a long time she had cared for nothing beyond that, to know that there was one human to share the dark with her.

Now Warrior came, immortal as she, as he, in one of its many persons. “Outsider,” it said, troubled, perhaps, in the perception of changes. “Unit called Tallen.”

iii

Tallen blinked in the twilight, watching them come…two, woman and man, robed in gauzy majat-silk. They wore it as if it were nothing, priceless though it was, as if their own will were cloak enough.

They stopped near to him, and Tallen shivered in their regard, that strange coolness and lack of fear. There was a mark on the man, beneath the eye and on the shoulder: azi. The old Tallen had reported such, but not such as he, whose gaze he could not bear. The mark on the woman was of jewels; of her kind too there were remembrances.

“Ab Tallen,” she said, strangely accented, “would be an old, old man.”

“Dead,” Tallen answered. “I’m his grandson. Your people remember him?”

Her eyes flickered, seemed possessive of secrets. She held out her right hand and he took it; hesitating at the strange warmth of the jewels that covered it.

“Raen Meth-maren,” she said. “Yes, there’s memory of him. Kind memory.”

“Your name is hers, that he mentioned.”

She smiled faintly, and questions of kinship went uninvited. She nodded to the man beside her. “Jim,” she said, and that was all.

Tallen took the other offered hand, regarded them both anxiously, for majat hovered about, escort, guards, soldiery—there was no knowing what.

“You delayed longer than you should,” she said.

“We had our years of trouble. I’m afraid there may have been landings here of a sort we’d not have allowed. Our apologies, for such intrusions.”

She shrugged. “Most have learned, have they not?”

That was truth, and chilling in her manner. “We’ve come here twice—peacefully, hunting some contact.”

“Now,” she said, “we’re pleased to answer you. Is it trade you want?”

He nodded, all his careful speeches destroyed, forgotten in that direct stare.

“I’m Meth-maren. Hive friend. Intermediary. I can arrange what you want.” She looked about her, and at him. “I speak and translate.”

“We need lab-goods, more than the jewels the farmers have been trading.”

“Then give us computers. You’ll get your lab products.”

“And some sort of licensing for regular trade.”

She nodded toward the plains, the beta-holds. “There are those who will deal with you as we arrange.”

“There’s no station any longer. It’s gone.”

“Crashed. We saw it, Jim and I. It fell into the sea, a long time ago. But stations can be rebuilt.”

“Come aboard my ship,” he invited her. “We’ll talk specifics.”

She shook her head, smiled faintly. “No, ser. Take your ship from the vicinity of the hive tonight, within the hour. Go to riverside. I’ll find you there with no trouble. But don’t linger near the hive.”

And she walked away, leaving him standing. The majat remained, and the man, who looked at him with remotely curious eyes and then walked away.

“All things end,” she said. “Does the Outside frighten you, Jim?”

“No,” he said. She thought it truth. Their minds were much alike.

“There’s Moriah.” She nodded in the direction of the port, where the only whole buildings in Newhope remained. “There’s the Reach or Outside. We’re human. There’s a time to remember that.”

He looked at her, saying nothing.

She linked her fingers in his, chitined hand in human one.

“It begins again,” she said.