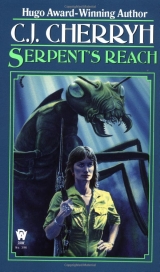

Текст книги "Serpent's Reach"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

BOOK SEVEN

i

More reports. Chaos multiplied, even on Cerdin.

Moth regarded the stacks of printouts with a shiver, and then smiled, a faint and febrile smile.

She looked up at Tand.

“Have you made any progress toward the Istran statistics?”

“They’re there, Eldest. Third stack.”

She reached for them, suffered a fluttering of her hand which scattered them across the table: too little sleep, too little rest lately. She drew a few slow breaths, reached again to bring the papers closer. Tand gathered them and stacked them, laid them directly before her. It embarrassed and angered her.

“Doubtless,” she said, “there are observations in some quarters that the old woman is failing.”

From Tand there was silence.

She brushed through the papers, picked up the cup on the table deliberately to demonstrate the steadiness of her right hand…managed not to spill it, took a drink, set it down again firmly, her heart beating hard. “Get out,” she said to Tand, having achieved the tiny triumph.

Tand started to go. She heard him hesitate. “Eldest,” he said, and came back.

Near her.

“Eldest—”

“I’m not in want of anything.”

“I hear rumours, Eldest.” Tand sank on his knee at the arm of her chair; her heart lurched, so near he was. He looked up into her face, with an earnestness surprising in this man…excellent miming. “Listen to me, Eldest. Perhaps…perhaps there comes a time that one ought to quit, that one could let go, let things pass quietly. Always there was Lian or Lian’s kin; and now there’s you; and is it necessary that things pass this time by your death?”

Bewilderment fell on her at this bizarre manoeuvre of Tand Hald; and within her robes, her left hand held a gun a span’s remove from his chest. Perhaps he knew; but his expression was innocent and desperately earnest. “And always,” she whispered in her age-broken voice, “always I have survived the purges, Tand. Is it now? Do you bring me warning?”

The last question was irony. Her finger almost pulled the trigger, but he showed no apprehension of it. “Resign from Council,” he urged her. “Eldest, resign. Now. Pass it on. You’re feeling your years; you’re tired; I see it…so tired. But you could step aside and enjoy years yet, in quiet, in peace. Haven’t you earned that?”

She breathed a laugh, for this was indeed a strange turn from a Hald. “But we’re immortal,” she whispered. “Tand, perhaps I shall cheat them and not die…ever.”

“Only if you resign.”

The urgency in his voice was plain warning. Perhaps, perhaps, she thought, the young Hald had actually conceived some softheartedness toward her. Perhaps all these years together had meant something.

Resign Council; and let the records fall under more critical eyes. Resign Council; and let one of their choice have his hand to things.

No.

She gave a thin sigh, staring into Tand’s dark and earnest eyes. “It’s a long time since Council functioned without someone’s direction. Who would take Eldest’s place? The Lind? He’s not the man for this age. It would all come undone. He’d not last the month. Who’d follow him? The Brin? She’d be no better.”

“You can’t hold on forever.”

She bit at her dry lips, and even yet the gun was on its target. “Perhaps,” she said, allowing a tremor to her voice, “perhaps I should take some thought in that direction. I was so long, so many, many years at Lian’s side before he passed; I think that I’ve managed rather well, have I not, Tand?”

“Yes, Eldest… verywell.”

“And power passed smoothly at Lian’s death because I had been so long at his side. My hands were at the controls of things as often as his; and even his assassination couldn’t wrench things out of order…because I was there. Because I knew all his systems and where all the necessary matters were stored. Resign…no. No. That would create chaos. And there are things I know—” Her voice sank to the faintest of whispers, “things I know that are life and death to the Family. My death by violence—or by accident—would be calamity. But perhaps it’s time I began to let things go. Maybe you’re right. I should take a partner, a co-regent.”

Tand’s eyes flickered with startlement.

“As I was with Lian…toward the last. I shall take a co-regent, whoever presents the strongest face and the most solid backing. I shall let Council choose.”

She watched the confusion mount, and kept a smile from her face.

“Young Tand,” she whispered, “that is what I shall do.” She waved her right hand, dismissing him; he seemed never to have realised where her left one was, or if he did, he had good nerves. He rose, grey and grim as iron now, all his polish gone. “I shall send out a message,” she said, “convoking Council for tomorrow. You must carry it You’ll be my courier.”

“Shall I tell the elders why?”

“No,” she said, knowing that she would be disobeyed. “I’ll present them the idea myself. Then they can have their time to choose. The transition of power,” she said, boring with sudden concentration into Tand’s dark eyes, “is always a problem in empires. Those which learn how to make the transfer smoothly…live. In general chaos who knows whomight die?”

Tand stood still a moment. Moth gave him time to consider the matter. Then she waved her hand a second time, dismissing him. His departure was as deliberate and graceful as usual, although she reckoned what disturbance she had created in him.

And, alone, Moth bowed her head against her hands, trembling. The trembling became a laugh, and she leaned back in her chair in a sprawl, hands clasped across her middle.

Not many rulers had been privileged to be entertained by the wars of their own successions, she reckoned; and the humour of seeing the Hald and their minions blinking in the light with their cover ripped away, publicly invitedto contend for power, while she still lived… That was worth laughter.

Her assassination had been prepared, imminent. Tand’s action was puzzling…some strange affliction of sentiment, perhaps, or even an offer relayed from the others; and with straight-faced humour she had returned the offer doubled. Of course they would kill her as soon as their choice was well-entrenched in power…but time… timewas the important thing.

She grinned to herself, and the grin faded as she gathered up the falsified Istran reports, stacked them with the others.

The Meth-maren would have need of time.

To leave this place, Cerdin and Council and all of them, and have such a place as the old Houses had been, old friends, dead friends—that was the only retirement for which Moth yearned, to find again what had died long ago, those who had built—instead of those who used.

But one of the folders was the Meth-maren’s, and Moth opened the record, stared morosely at the woman the child had become.

The data was random and the cross-connections inexplicable, and her old age grew toward mysticism, the only sanity…too much knowledge, too wide a pattern.

Lian also must have seen. He had complained of visions, toward the last, weakness which had encouraged assassins, and hastened his death.

He had died riveted in one of those visions, trembling and frothing, a horror that left no laughter at all in Moth.

She had had to do it.

“Eggs,” Lian had cried in his dying, “eggs…eggs…eggs…eggs,” as if recalling the beta children, the poor orphaned creatures, the parentless generation—the thousands growing up too soon, cared for en masse, assembly lined into adulthood, men and women at ten, to care for others, and others…to bear natural children at permission, as they slid all things at permission, forever. Give them luxury, Lian had said once. Corrupt them, and we shall always control them. Teach them about work and rewards, and reward them with idleness and ambition. So we will always manage them.

So betas, seeking idleness, created azi.

Eggs…eggs…eggs…eggs.

Eggs of eggs.

Moth shuddered, reliving the fissioning generations who had spawned all reality in the Reach.

Seven hundred years. From one world to many worlds, a rate of growth no longer controlled.

Eggs.

Potential.

I am the last, Moth thought, who was once human. The last with humanity as it once was. Even the Meth-maren is not that.

Least of all…that.

Eggs making eggs.

Family, she thought, and thought of an old saying about absolute power, and absolute corruption.

Only the azi, she thought, lack power.

The azi are the only innocents.

ii

Pol Hald sat down, propped his slim legs on a table, folded his hands and looked about him with a shrug of amusement.

Raen took the drink that Jim served her and leaned back, stared balefully as Pol accepted his and looked Jim up and down, drawing the obvious conclusions. Jim glanced down, an azi-reaction to such attention.

“Thank you, Jim,” Raen said softly. For a very little she would have asked Jim to sit down and stay, but Pol was another matter than the ITAK board…cruel when he wished to be; and he often wished to be.

Jim vanished silently into the next room. Warrior did not. The majat sat in the corner next to the curio table, rigidly motionless as a piece of furniture.

“Beta-ish,” Pol observed of the decor, of the whole house in general, a flourish of his hand. “You’ve a bizarre taste, Meth-maren. But the azi shows some discrimination.”

“What are you doing here?”

Pol laughed, a deep and appealing chuckle. “It’s been eighteen years since we shared a supper, Meth-maren. I had a mad impulse for another invitation.”

“A far trip for little reward. Does Ros Hald’s table not suffice?”

He had pricked at her. She flicked it back doubled, won a slight annoyance of him. That gaunt face had not changed with the years; he had reached that long stage where he would not. She added up numbers and reckoned at least over seventy. Experience. The gap was narrowed, but not by much.

“I’ve followed you for years,” he said. “You’re the only Meth-maren who ever amused me”

“You’ve done so very quietly, then. Did the Hald send you?”

“I came.” He grinned. “You have a marvellous sense of humour. But your style of travel gave me ample time to catch up with you.” He drank deeply and looked up again, set the glass down. “You know you’ve set things astir.”

She shrugged.

“They’ll kill you,” Pol said.

“They?”

“Not I, Meth-maren.”

“So why are you here?” she asked, mouth twisted in sarcasm. “To stand in the way?”

He made a loose gesture, looked at her from half-lidded eyes. “Meth-maren, I am jealous. You outdid me.” He laughed outright. “I’ve studied to annoy Council for years, but I’ll swear you’ve surpassed me, and so young, too. You know what you’re doing here?”

She said nothing.

“I think you do,” he said. “But it’s time to call it off.”

“Take yourself back to Cerdin, Pol Hald.”

“I didn’t come from Cerdin. I heard. I was willing to come out here. You’re my personal superstition, you see. I don’t want to see you go under. Get out of here. Now. To the other side of the Reach. They’ll understand the gesture.”

She rose. “Warrior,” she said.

Warrior came to life, mandibles clashing, and reared up to its full height. Pol froze, looking at it.

“Warrior, tell me, of what hive is this Kontrin?”

“Green-hive,” Warrior said, and boomed a note of majat language. “Green-hive Kontrin.”

Pol moved his chitined right hand, a flippant gesture that was a satire of himself. “Am I to blame for the choice of hive? It’s Meth-maren labs that set the patterns, that reserved blue for chosen friends…of which we were not.”

“Indeed you were not.”

Pol rose, walked to the window, walked back again, within reach of Warrior, deliberate bravado. “You’re far beyond the limits. Do you know…do you understand what deep water you’re into?”

“That my House died for others’ ambitions? That something was set up two decades ago and no one has stopped it? How are they keeping it from Moth? Or are they?”

Pol’s dark eyes flicked aside to Warrior, back to her. “I grow nervous when you become specific. I hope you’ll consider carefully before you make any irrevocable moves.”

“I learned, Hald. You taught me a lesson once. I’ve always held a remote affection for you on that account. No rancour. We said once we amused each other. Will you answer me now?”

He made a shrug of both hands. “I’m not in good favour among Halds. How could I know the answers you want?”

“But what you know you won’t tell me.”

“Moth has not long to live. That I know. For the rest of what I know: the Halds are your enemies…nothing personal, understand. The Halds want what Thel reached for.”

“And no one has undone what Eron Thel did.”

Pol made a gesture of helplessness. “I don’t know; I don’t know. I protest: I am not in their confidence.”

It was possibly true. Raen kept watching the hands and the eyes, lest a weapon materialise. “I appreciate your concern, Pol.”

“If you’d take my advice, get out of here…clear over to the far side, they would understand, Raen a Sul. They’d read that as a clear signal. Capitulation. Who cares? You’ll outlive them if you guard your life. Running now is your only protection. My ship is onworld. I’d take you there. The Family wouldn’t harm you. The Halds may not take me into their intimate confidence, but neither will they come at me.”

She started to laugh, and saw Pol’s face different from how she had ever known it, drawn and tense…no laughter, for one of a few times in his irreverent life.

“Go away,” she said very softly. “Get yourself to that safety, Pol Hald. You’ll survive.”

He said nothing for a moment, looked doubtful. “What is it you have in mind?”

She did laugh. “I wonder, Pol Hald, if you don’t surpass me after all. Maybe they did send you.”

“I think you’ll hear from the Family soon enough.”

“Will I? Where’s Morn, Pol?”

He shrugged. “I don’t know. Cerdin, maybe. Or near these regions. It could be Morn. Or Tand. Or one of the Ren-barants. Or maybe none of them. When Moth falls, they’ll pull your privileges, and then you’ll be deaf, dumb and blind, grounded on Istra.”

“Moth’s on my side, is she?”

“She has been. I don’t know who it will be. Truth. I started from innerworlds when I was sure where you’d gone…when I knew for certain it wasn’t a cover. Morn headed the other way. Tand moved inworlds, even earlier than that. He’s likely with Moth. I’m handing you things that would break the Reach wide open if you called Moth.”

“You’re challenging me to do that?”

Again a shrug, a hint of mockery. “I’m betting the old woman knows a good part of it already.”

“Or that it’s already too late? It would take eight days for the shockwave to reach us.”

“Possible,” he said. “But not my reason.”

“Men you believe I don’t want the break right now. You could be mistaken.”

Pol said nothing.

“You don’t plan,” Raen said in a bard voice, “to be setting up on Istra”

“I’ve a problem,” Pol said. “If I go back, I’ll be called in; and if I run alone…they’ll know I heard something here that made it advisable. I’ve put myself in difficulty on your account, Meth-maren.”

“If I believed any of it”

Pol made another of his elaborate gestures of offence. “I protest. I shall go back to my ship and wait until you think things over in a clearer mind. Someone else will come, mark me.”

“Ah, I don’t doubt that much. And help would be convenient. But likewise I remember the front porch at Kethiuy. You knew. You knew when you were talking to me. Didn’t you?”

A profound sobriety came on Pol’s face. He lowered his eyes, raised them steadily. “I knew, yes. And I left, with the rest of the Halds, before the attack. Revenge, Meth-maren, involving another generation. It had nothing to do with you.”

“Now it does.”

He had no answer for that. Neither did he flinch.

“This one’s mine,” she said. “I always had profound respect for your intelligence, Pol Hald. You were in Hald councils before I was born. You were alive when the Meth-marens split, Sul from Ruil. You have contacts I don’t. You’ve access to Cerdin. You’ve been staying alive and embarrassing Council twice my whole lifespan. You knew, back in Kethiuy. You’re telling me now that you don’t figure precisely what’s in others’ minds?”

Pol drew a long breath, nodded slowly, looking down. “The plan was, you understand, to break out of the Reach. That was Thel’s idea. To build. To breed. And it’s all here on Istra, isn’t it? You’ve put it together for yourself.”

“Enough to take it apart.”

“They’ll kill you for sure. They’ll drag Moth down and kill you before they let you expose their operation.”

“Their.”

“Their. I’m not in favour. I go my own way. As you do. I’ll run when the time comes. I’ll stay, while the mood takes me. Only you won’t have that luxury. Is it worth this much, your vendetta?”

“It’s beyond argument.”

He looked at Warrior, stared into the faceted eyes, glanced back with a faint touch of revulsion. “Hive-masters. It’s that, isn’t it? Ruil Meth-maren tried to use the hives. And Thel wanted to use them. Look where that took us.”

“No one,” she said, “ usesthe hives. Hive-master was a Ruil word. Sul never used it And Thon’s still playing that dangerous game. Are red-hivers out again on Cerdin?”

“They make gifts to all the old contacts.”

Warrior’s palps flicked nervously. “Pact,” it said.

Pol glanced that way in apprehension.

“Do you not understand the danger?” Raen asked hint “The hives don’t have anything to gain…nothing Hald could want out of the exchange.”

“Azi,” Pol said. “They ask for more azi. For more land. More grain.”

“Hives grow,” said Warrior. “Hives here—grow.”

Raen looked on Warrior. Truth. It was clear truth. It fit with all the knowledge elsewhere gathered.

“Don’t you understand?” she appealed to Pol. “Doesn’t Council? Who talked first of this expansion? Thel, Ruil…or red-hive?”

“Thel claimed unique partnership, claimed that even Drones could be brought into partnership with humans.”

Her heart beat very fast. She laid her hand on one of Warrior’s auditory palps, stroked it gently, gently. “O Pol. Don’t they realise? Drones are the Memory. Humans can’t touch that.”

Pol shrugged, and yet his dark eyes were quick with worry. “The Meth-marens are dead. The hive-masters are dead, all but you. And Council doesn’t have access to you, does it? Moth’s kept saying that you were important”

“I’m flattered,” she said hoarsely. “Hive-masters. Ruil deluded themselves. They were never hive-masters. They listened to the hives. Get out of here. Take your ship. Tell them they’re all mad. I’ll give you reasons enough to tell them.”

He shook his head. “I wouldn’t live to get there. And they wouldn’t listen. Can’t. It’s gone too far. Moth will be dead by the time I could get there. Eight days, message-time or ship-time, at quickest. I couldn’t—couldn’t get there in time.”

“And someone’s on his way here.”

“There’s no way not.”

Pol was talking clear sense. She continued to soothe Warrior, aware it was recording, aware of the nervous tremor of the palp against her hand. She felt it calm at last. “There are extensions of ITAK on the other continent. Are there blues with the other city, Warrior?”

“Yess. All hives, red, gold, green, blue. New-port”

“Same-Mind, Warrior?”

“Same-Mind.”

“No queen.”

“Warriorss. Workerss. From this-Hill.”

She looked at Pol. “Suppose that I trusted you. Suppose that I asked you to do me a small favour. Have you your own staff?”

“Twelve azi. The ship is mine. My entire estate. I’m mobile. In these times it seems wise.”

“I haven’t an establishment on the other continent.”

“You plan to take me out of the way.”

“You can take West and be sure of the situation there in the matter of a day or two.”

“You may not have that much time. They’ll stop you. I mean that”

“Then it’s wise that I cultivate you, isn’t it? If they pull my authorisations you’ll still have yours, won’t you, Pol Hald?”

“You have a dazzling mutability. You’d rely on me?”

“One does what one must.”

“You’d have my neck in the jaws with no compunction, wouldn’t you?”

“I’m figuring you started from innerworlds first and farthest out. So there’s a little time yet. You can do me that small service and still have time to run. And I’d run far, Pol. I would, in your place.”

All posing fell aside. He stared at her. “I’ve told you something. I wish I understood the extent of it.”

“The Halds should have asked my help. Or Moth should have. If they’d asked, I might have come.” She gave Warrior’s auditory palp a light brush, and Warrior turned its head, reacted in slight pleasure. “It’s good to see you, Pol. I’d not say that of any of the rest of the Family, I assure you. My old acquaintances no longer interest me. The Family…no longer interests me. I’ve found here what you’ve been searching for all your life.”

“And what do you take that to be, Raen a Sul?”

“The Edge. That which limits us”

“You don’t have Ros Hald’s ambitions.”

She laughed, which was no laughter. “Mine are yours. To push until it gives. Here’s the stopping-place. Beware red-hive. You understand me?”

“You have disquieted me.”

“You never liked peace”

“What shall I look for in West?”

“Guard-azi. Buy up those you can. Ship them to East, to the Labour Registry. Arms as well.”

“You’re planning civil war.”

She smiled again. “Tell the estate-holders in West…and ITAK there…to prepare for storm.”

“How can I, when I don’t know what you have in mind?”

“It’s your choice. Go or stay”

“I know my choices, youngster.”

“You’d better get yourself clear of this house, in any case. There’ll be blue-hive thick about here in a little while, and that hand of yours is no guarantee of friendship. Get out of Newhope, in either direction you choose.”

He put on a long face. “I’d thought of dinner, alas; and more things after.”

“Later, Pol Hald. I confess you tempt me.”

A twinkle danced in his eye, a favourite pose. “Then I’m not without hope. Alas, you’ve your azi for consolation, and I’m not without my own. Sad, is it not?”

“The time will come.”

He bowed his head.

“You know my call number. It never changes.”

“You know mine.”

“Betas on Istra,” she said, “have played the same dangerous game as Hald and Thon. Red-hive gives them gifts. I’ll warrant red-hive walks where it will in West.”

“I’ve no skill with majat.”

“Keep it that way. Refuse to be approached. Shoot on the least excuse.”

“Hazard,” Warrior broke in, coming to life again. “Green-hive Drone, take care: danger. Red-hive kills humans, many, many, many. You are not green-hive Mind. No synthesis. None.”

“What’s it saying?” Pol asked. “I can never make sense of them.”

“Perfect sense. It knows you’re naïve of majat, and it warns you that without hive-friendship, green-hive chitin is no protection to you, even from greens. Red-hive and even greens have learned to kill intelligences. Red-hive has learned to make agreements with minds-that-die, and no longer has trouble with death. What’s more…they’ve learned to lie. Consider the hive-Mind, Pol; consider that those who lie to majat have to be unMinded. But they can lie to humans without it…a profound discovery. Red-hive has gone as far from morality as majat can go. Hald and Thel and Thon helped…or otherwise. Get. out of here. You’ve not much time. Be careful at the port. Are you armed?”

He moved his hands delicately. “Of course.”

She offered her hand, warily; he took it, with a wry smile.

“I’ll give you West,” he said, letting go her hand. “Is that all you want?”

She grinned. “I’ll be content with that.” And soberly: “Keep within reach of your ship, Pol. It’s life.”

He took his leave, let himself out. In a moment she heard a car start and ease down the drive. She went to housecomp to open the gate, did so, picked him up briefly on remote. He cleared the gate and she closed it.

Warrior came, hovered at her shoulder. “This-unit heard things of other hives. Redsss. Trouble.”

“This-unit is concerned, Warrior. This-unit begins to think that the hives know more than you’ve told me.”

It drew back, jaws clicking. “Red-hive. Red-hive is—” It gave a booming and shrill of majat language. “No human word, Kontrin-queen. Long, long this red-hive, gold-hive—” Again the combination of sound, discord. “Red-hive is full of human-words: push-push-eggs-more-more.”

“Expansion. They want expansion. Growth.”

Warrior tried to assimilate that. It surely knew the words; they did not satisfy it.

“Synthesis,” it said finally. “Red-hive messengers come. Many, many. Red-hive—easy, easy that messengers come. Kontrin permit Goldss, yes. Greens, sometimes. Many, many, no blues.”

“I know. But Kalind blue reached you. What did it tell you?”

“Kethiuy-queen…many, many, many messengers, reds, golds, greens. No blues. Blues have rested, not part of push-push-push. No synthesis. Now blue messenger. We taste Cerdin-Mind.”

“Warrior. What was the message?”

“Revenge,” Warrior said, which was the essence of Kalind blue. And suddenly auditory palps flicked left. “Hear. Others.”

She shook her head. “I can’t hear, Warrior. Human range is small.”

It was listening. “Blues, they say. Blues. They are coming. Many-many. Goodbye, Kethiuy-queen.”

And it fled.

iii

The sun was almost below the horizon; it was no longer necessary to wear cloaks or sunsuits or to fear for the eyes. And the garden was alive with majat.

Raen kept Jim by her, constantly, and Max and Merry as well, not trusting the nervous Warriors. She walked the garden, making sure that Warriors saw their presence clearly, to realise that they justly belonged there.

And suddenly others were there, rag-muffled figures, swarming over the back garden wall among the Warriors; and other majat accompanied them, smaller, with smaller jaws: Workers, a horde of them.

Ragged human figures came to her and sought touch with febrile hands and eyes visored even at dusk, and their movements were strange, nervous. One and several others unmasked, sought mouth-touch with Jim and Max and Merry end danced away from their vicinity when Raen bade them go.

“What are they?” Jim asked, horror in his voice.

“Don’t worry for them,” Raen said. “They belong to the majat. They have majat habits.” And seeing how all three azi reacted to their majat counterparts: “Blue-hive azi, go in, go inside the building, seek low-level and settle there.”

“Yes,” they said together, song-toned, and with that mad-blind fix of hive-azi stares. They scampered off, to seek the basement of the house, the dark places where they would be most at home.

Workers set to work without asking, began to pry up stones with their jaws, began to dig, through the pavings, into the moist earth.

And suddenly there was a buzz from the front gate.

Raen swore, waded off through the crowd of Warriors, beckoning Jim and Max and Merry to come with her. “Warrior,” she shouted at the nearest. “Keep all majat out of sight behind the house. No enemies. No danger. Just stay here.” And to Max and Merry: “Get down by the gate. I imagine that’s the new azi coming in. You’re in charge of them. See they don’t wander loose. Get them in strict order and check them off against the invoice, by numbers, visually.”

They hurried off at a run. She went inside with Jim as her shadow, unsealed the gate from the comp center when she saw the trucks by remote: they bore the Labour Registry designation. She kept watching, while the trucks disgorged azi and supplies, while Merry and Max called off numbers and ranged the men in groups of ten. The men stood; the boxes formed a square in the front garden. As each truck emptied, it pulled out, and when the last vehicle cleared the gate, Raen closed it and set the alarm again.

“They’ll not like the majat at all,” Raen said. “Jim, go find one of the quieter Warriors and ask it to come to the front of the house with you—alone. Better they see one before they see all of them”

He nodded and went. Raen put the outside lights on and went out the front door, walked out into the midst of the orderly groups, two hundred six men, by tens.

Max and Merry were checking numbers as she had said, a process the brighter lights made easier. Each was read, not by the stencil on the coveralls, but by the tattoo on the shoulder; and each man passed was directed into military order over by the portico. Neat, precise, the team of Max and Merry; and the two hundred were minds precisely like theirs…all too precisely, having come from the same tapes.

Every figure stiffened, looked houseward. Raen glanced and saw Jim with his unlikely shadow slow-stepping along in close company. “There are many such here,” Raen said before panic could take hold. “ Ihold your contracts. I tell you that you’re very safe with these particular majat. They’ll help you in your duties, which are to protect this house. Understood?”

Each head inclined, the fix of their eyes now on her. Two hundred men. In the group were many who were duplicates, twin, triplet, quadruplet sets, alike even to age. There were two more Maxes and another Merry. They could accept. They would accept her and the majat as they would accept anything which held their contracts. It was their psych-set. Like Max and Merry, they fought only when they were directed, only when their contract-holder identified an enemy. But for their own lives, they would scarcely put up resistance. Did not. Until things were clear to them, they were docile. Warrior exercised curiosity about them, stalked down near them. They bore this: their contract-holder was present to instruct them if instructions were to be given.

Guard-function.

Specificity, Itavvy had called it.

“Warrior,” she said, “come.” And when it had joined her, with Jim shadowing it, she soothed it with a touch and kept it by her, an act of mercy.

The process continued. But by one man both Max and Merry delayed, looked closely at the mark, disputed. “Sera,” Max called.

The man bolted. Warrior moved. “No!” Raen yelled, but Warrior was deaf to that, auditory palps laid back, a blur of motion. Azi scattered.

But it was Max and Merry who had the fugitive; Raen raced through the chaotic midst, calmed the anxious Warrior. Jim stayed with her. Other azi stayed about, sober-faced, stunned, perhaps, that one of their number had done violence.

The azi in Max’s grip stopped fighting, gazed past Raen’s shoulder and surely understood what he had narrowly escaped. He was a man like the others, shave-headed, grey clad, a number stencilled on his coverall; but Merry pulled back the cloth from his shoulder and showed the tattoo as if there were something amiss.