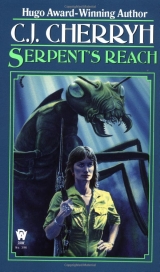

Текст книги "Serpent's Reach"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

BOOK THREE

i

There was, in the salon of the Andra’s Jewel, an unaccustomed silence. Normally the first main-evening of a voyage would have seen the salon crowded with wealthy beta passengers, each smartly turned out in expensive innerworld fashions, tongues soon loosened with drink and the nervousness with which these folk, the wealthy of several worlds, greeted their departure from Kalind station. There were corporation executives and higher supervisors, and a scattering of professionals of various fields dressed to mingle with the rich and idle, estate-holders, of whom there were several.

This night there were drinks poured: azi servants passed busily from table to table, the only movement made. The fashionable people sat fixed in their places, venturing furtive glances across the salon.

They were the elite, the powers and movers of beta society, these folk. But they found themselves suddenly in the regard of another aristocracy altogether.

She was Kontrin. The aquiline face was the type of all the inbred line, male or female, in one of its infinite variations. Her grey cloak and bodysuit and boots were for the street, not the society of the salon, elegant as they were. It was possible that they masked armour…more than possible that they concealed weapons. The chitinous implants which covered the back of her right hand were identification beyond any doubt, and the pattern held unlimited credit in intercomp, in any system of the Reach…unlimited credit: the money for which wealthy betas strove was only a shadow of such entitlement.

She smiled at them across the room, a cold and cynical gesture, and the elite of the salon of Andra’s Jeweltried to look elsewhere, tried to pursue their important conversations in low voices and to ignore the reality which sat in that corner of empty tables. Suddenly they were uncomfortable even with the azi servants who passed among them bearing drinks…cloned men, decorative creations of their own labs, as they themselves had been spawned wholesale out of the Kontrin’s, seven hundred years past. Proximity to the azi became suddenly… comparison.

The party died early. Couples and groups drifted out, which movement became a general and hasty flow toward the doors.

Kont’ Raen a Sul watched them go, and in cynical humour, turned and met the eyes of the azi servant who stood nearest. Slowly all movement of the azi in the salon ceased. The servant stood, held in that gaze.

“Do you play Sej?” she asked.

The azi nodded fearfully. Sej was an amusement common throughout the Reach, in lower and rougher places. It was a dicing game, half chance and some part skill.

“Find the pieces.”

The azi, pale of face, went among his companions and found one who had the set. He activated the gaming function of the table for score-keeping, and laid the three wands and the pair of dice on the table.

“Sit down,” said Kont’ Raen.

He did so, sweating. He was young, several years advanced into the service for which he existed. He had been engineered for pleasing appearance and for intelligence, to serve the passengers. He had no education beyond that duty, save what rumour fed him and what he observed of the betas who passed through the salon. The smooth courtesy which he had deepstudied in his training gave him now the means to function. Other azi stood about, stricken by his misfortune, morbidly curious.

“What’s your name?” she asked.

“Jim,” he said. It was the one choice of his life, the one thing he had personally decided, out of a range of names which belonged to azi. Only azi used it, and a few of the crew. He was vastly disturbed at his loss of anonymity.

“What stakes?” she asked, gathering up the wands.

He stared at her. He had nothing, being property of the line, but his name and his existence.

She looked down and rolled the wands between her hands, the one glittering with chitin, and infinite power. “It will be a long voyage. I shall be bored. Suppose that we make wager not on one game, but on the tally of games.” She laid the wands down under her right hand. “If you win, I’ll buy you free of Andra Lines and give you ten thousand credits for every game you’ve won. Ten rounds an evening, as many evenings as there are in my voyage. But you must win the series to collect: it’s only on the total of games, our wager.”

He blinked, the sweat running into his eyes. Freedom and wealth: he could live out his life unthreatened, even in idleness. It was a prize beyond calculation, and not the sort of luck any azi had. He swallowed hard and reckoned what kind of wager he might have to return.

“But if I win,” she continued, “I shall buy your contract for myself.” She smiled suddenly, a bleak and dead smile. “Play to win, Jim.”

She offered him first cast. He took up the wands. The azi in the salon settled silently, watching.

He lost the first evening, four to six.

ii

A small, tense company gathered in the stateroom of the ISPAK Corporation executive. There were other such gatherings, private parties. The salon was still under occupation on this third evening. No one ventured there any longer save during the day. There remained available of course the lower deck lounge, where the second-class passengers gathered; but they were not willing to descend to that society, not under the circumstances. Their collective pride had suffered enough.

“Maybe she’s going to Andra,” someone suggested. “A short trip…perhaps some bizarre humour…”

The Andran executive looked distressed at that idea. Kontrin never travelled commercial; they engaged ships of their own, a class of luxury unimaginable to the society of Andra’s Jewel,and separate. Impatience, near destination…even the possibility of assassins and the need to get offworld by the first available ship: the surmise made sense. But Andran affairs did not want a Kontrin feud: there was trouble enough without that. This one…this Kontrin, did things no Kontrin had ever done, and might do others as unpredictable. Worse, the name Raen a Sul stirred at some vague memory, seldom as names were ever exchanged between Kontrin and men… Men… Betawas not a term men used of themselves.

This one had been on Andra, and might be returning. Majat were where they ought not to be, and suddenly Kontrin were among them. Until lately it had been possible to ignore Kontrin doings entirely; a man could live years and not so much as see one; and now one came into their midst.

“There’s a rumour—” someone else said, and cleared her throat, “there’s a rumour there’s a majat aboard.”

Another swore, and there was a moment’s silence, nervous glances. It was possible. Majat travelled, rarely, but they travelled. If it were so, it would be somewhere isolate, sinking into dormancy for the duration of the flight. Majat parted from the hive became disoriented, dangerous: this one would have awakened long enough to have performed its mission, whatever it was, and to secure passage home—function assigned it by the hive. So long, it might remain sane, having clear purpose and a goal in sight. Thereafter, it must sleep, awakening only in proximity to its hive.

There were horror tales of majat awakening prematurely on a ship; and majat horror tales were current on Andra, on Kalind, on Meron, unreasoning actions, killings of humans. But the commercial lines could no more refuse a majat than they could have refused the Kontrin. It was a question of ownership, of the origins of power in the Reach, and some questions it was not good to raise.

Silence rested heavily on the gathering, which sat uncomfortably on thinly padded furniture in an anteroom designed for smaller companies. Ice rattled in glasses. The executive cleared his throat.

“Kontrin don’t travel alone,” he said. “There are always bodyguards. Where are they?”

“Maybe they’re…some of us,” a Kalinder suggested. “I’d be careful what I said.”

No one moved. No one looked at anyone else. No Kontrin had ever done such a thing as this one had done: they feared assassination obsessively, guarding the immortality which distinguished their class as surely as did the chitin-patterns. That was another cause by which men found it difficult to accept the presence of a Kontrin, for her lifespan was to theirs far longer than theirs was to that of the azi they created. Men were likewise designated for mortality, as surely as the Kontrin had engineered themselves otherwise, and kept that gift from others. It was the calculated economy of the Reach. Only the owners continued. Men were to the Kontrin…a renewable resource.

Someone proposed more drinks, They played loud music and talked in whispers, only to those they knew well, and eventually this party too died.

There were other gatherings in days after, in small number, by twos and by threes. Some stayed entirely in their staterooms, fearing the nameless threat of meetings in the corridors, unnerved by what was happening on worlds throughout the Reach. If there was a majat aboard, no one wanted to find it.

The game continued in the salon. Jim’s luck improved. He was winning, thirty-seven to thirty-three. The other azi’s eyes followed the fall of the wands and the dice as if their own fortunes were hazarded there.

The next evening the balance tilted again, forty to forty.

iii

Andra’s Jeweljumped and made slow progress to Andra station. Ten grateful first-class passengers disembarked and the Kontrin did not. The majority of lower-deck passengers left; more arrived, short-termers, for Jim, and three first-class, bound for Meron. The game in the salon stood at eighty-four and eighty-six.

The Jewelcrept outward in real-space, for Jim; again for Sitan and the barrenness of Orthan’s moons; made jump, for glittering Meron. Such passengers who remained, initiates of the original company, were dismayed that the Kontrin did not leave at Meron: there had even been wagers on it. The occupation of the salon continued uninterrupted.

The score stood at two hundred forty-two to two hundred forty-eight.

“Do you want to retire?” Kont’ Raen asked when the game stood even. “I’ve had my enjoyment of this. I give you the chance.”

Jim shook big head. He had fought his way this far. Hope existed in him; he had never held much hope, until now.

Kont’ Raen laughed and won tine next hand.

“You should have taken it,” an azi said to Jim that night. “Kontrin don’t sell their azi when they’re done with them. They terminate them, whatever their age. It’s their law.”

Jim shrugged. He had heard so already. Everyone had had, to tell him so. He worked the dice in his clenched hand. and sat down on the matting of the azi quarters. He cast them again and again obsessively, trying the combinations as if some magic could change them. He no longer had duties on the ship. The Kontrin had marked his fatigue and bought him free of duties. He was no longer subject to ration: if he wanted more than his meals, he did not have to rely on tips to buy that extra He seldom chose to go beyond ration, all the same, gave once or twice when he had been far ahead and his appetite improved. He cast the dice now, against some vague superstition formed of these empty days. He played himself, to test his run of luck.

He could not have quit, the game unfinished, could not go back to the others, to being one of them, and exist without knowing what he had given up. He would always think that he might have been free and rich. That would always torment him. The Kontrin had sensed this, and therefore she had laughed. Even he could understand the irony.

iv

Andra’s Jewelreached Silak and, docked. Ship will continue to Istra, the message flashed to the three passengers who should have disembarked there with the others, to seek connections further. So grand a ship as Andra’s Jeweldid not make out-planet runs with her staterooms empty. But the passengers who had packed, unpacked, with the desperate fear that they would do better to disembark anyway and seek other transportation, however long they had to wait. A few more passengers boarded. The Jewelvoyaged out, ghostly in her emptiness.

“It’s the Kontrin,” the ITAK envoy whispered to his wife. “She’s going to Istra.”

The woman, his partner-in-office, said nothing, but glanced anxiously at the intercom and its blank screen, as if this might be carried to other ears.

“What other answer?” The Istran shaped the words with his lips, soundlessly. “And why would they come in person? In person, after all?”

The woman regarded him in dread. Their mission to Meron, dismal failure, had been calamity enough. It was their misfortune that they had chosen the Jewelfor their intermediate link to Silak—tempted by the one brief extravagance of their lives, compensation for their humiliation on Meron. They were executives in a world corporation; they had attempted to travel a few days in the grand style of their innerworld counterparts, once, once, to enjoy such things, foreseeing ruin awaiting them on Istra. “We should have gotten off this ship at Silak,” she said, “while we had the chance. There’s only Pedra now, and no regular lines from there. We should have gotten off. Now it’s impossible she wouldn’t take notice of it. She surely knows we’re Istran.”

“I don’t see,” he said, “how she could be involved with us. I don’t. She’s from beforeMeron. Unless—while we were stalled on Meron—some message went through to Cerdin. I asked the azi where she boarded. They said Kalind. That’s only one jump from Cerdin.”

“You shouldn’t have asked the azi.”

“It was a casual question.”

“It was dangerous.”

“It was—”

“Hush! not so loud.”

They both looked at the intercom, uncomfortable in its cyclopsic presence. “It’s not live,” he said.

“I think she owns this ship,” the woman said. “That’s why there aren’t any guards visible. The whole crew, the azi—”

“That’s insane.”

“What else, then? What else makes sense?”

He shook his head. Nothing did.

v

They reached barren Pedra, and took on a straggle of lower-deck passengers, who gaped in awe at the splendour of the accommodations. Nothing the size of the Jewelhad ever docked at Pedra. There were no upper-deck passengers: one departed here, but none boarded.

The game stood at four hundred eighteen to four hundred twelve. Bets had spread among the free crew. Some of them came and watched as the azi’s lead increased to thirteen. It was the widest the game had ever been spread.

“Your luck is incredible,” the Kontrin said. “Do you want to quit?”

“I can’t,” Jim said.

The Kontrin nodded slowly, and ordered drinks for them both.

Andra’s Jewelmade out from sunless Pedra and jumped again. They were in Istran space, beta Hydri two, snake’s-tail, the Outside’s contact point with the Reach.

There were, after the disorientation of jump, a handful of days remaining.

The game stood at four hundred fifty-nine to four hundred fifty-one. Midway through the evening it was four hundred sixty-two to four hundred fifty-three, and there was still a deep frown on the face of Kont’ Raen. She cast the wands governing aspect of the dice. They turned up star, star, and black. The aspects were marginally favourable. With black involved, she could have declined the hand and cancelled it, passing the wands to Jim for a new throw. She simply declined the first cast of the dice. The azi threw six and she threw twelve: she won the star and it took next star automatically. twenty-four. The azi declined first throw on the deadly black. She threw four; the azi threw twelve. The azi had won black, cancelling his points in the game. A low breath hissed from the gallery.

“Do you concede?” Kont’ Raen asked.

Jim shook his head. He was tired; his position in this game was all but hopeless: her score was ninety-eight; his was zero…but it was his option, and he never conceded any game, no matter how long and wearing. Neither did she. She inclined her head in respect to his tenacity and yielded him the wands. His control of the hand, should black turn up, afforded him a marginal chance of breaking her score.

And suddenly there was a disturbance at the door.

Two passengers stood there, male and female, betas. The azi of the salon, so long without visitors to serve of evenings, took an instant to react. Then they hurried about preparing chairs and a table for the pair, taking their order for drinks.

The game continued. Jim threw two ships and a star. He won the ships and had twenty; Raen won the star and took game.

“Your hundred fifty-four,” she said quietly, “to your four hundred fifty-two.”

Jim nodded.

“Take first throw.”

He shook his head; one could refuse a courtesy. She gathered up the wands.

A chair moved. One of the passengers was coming over to them. Raen hesitated in her cast and then looked aside in annoyance, the wands still in her hand.

“I am ser Merek Eln,” the man said, and gestured back to the woman who had also risen. “Sera Parn Kest my wife.”

Raen inclined her head as if this were of great moment to her. The betas seemed to miss the irony. “Kont’ Raen a Sul,” And with cold courtesy. “Grace to you both.”

“Are you…bound for Istra?”

Raen smiled, though coldly. “Is there anything more remote?”

Merek Eln blinked and swallowed. “The ship must surely start its return there. Istra is the edge of the Reach.”

“Then that must be where I am bound.”

“We…are in ITAK, Istran Trade…”

“…Association, Kontrin-licensed. Yes. I’m familiar with the registered corporations.”

“We offer our assistance, our—hospitality.”

Raen looked him up and down, and sera Kest also. She let the silence continue. “How kind,” she said at last. “I’ve never had such an offer. Perhaps I’ll take advantage of it. I don’t believe there are other Kontrin on Istra.”

“No,” Eln said faintly. “Kontrin, if you would care to discuss the matter which brings you here—”

“I don’t.”

“We might…assist you.”

“You aren’t listening, ser Merek Eln. I assure you, I have no interests in ITAK matters.”

“Yet you chose Istra.”

“Not I.”

The man blinked, confused.

“I didn’t divert the ship,” Raen said.

“If we can be of service—”

“You’ve offered me your hospitality. I’ve said that I shall consider it. For the moment, as you see, I’m engaged. I have four games yet to go this evening. Perhaps you’ll care to watch.” She turned her back on ser Merek Eln and sera Kest, looked at Jim, who waited quietly. Azi were accustomed to immobility when not pursuing orders. “What do you know of Istra?” she asked him.

“It’s a hive world. A contact point with Outside. Their sun is beta Hydri.”

“ Thecontact point. I don’t recall any Kontrin going there recently. I knew one who did, once. But surely there are some amusements to be had there.”

“I, don’t know,” Jim said very faintly, quieter in the presence of the Istrans than he had been since the beginning. “I belong to Andra Lines. My knowledge doesn’t extend beyond the range of my ship.”

“Do these folk make you nervous? I’ll ask them to leave if you like.”

“Please, no,” Jim said hoarsely. Raen shrugged and made the cast.

It came up three stars. She took first throw. Twelve. Jim made his: two. Raen gathered thirty-six points. Jim took up the wands as if they were venomed, threw three whites. Raen won the dicing and automatically took game.

“Your luck has bit a sudden downward turn,” Raen said, gathering up the three wands. She passed them to him. “But there’s still margin. We’re at four hundred fifty-five to your four hundred sixty-two.”

He lost all but the last game, setting the tally at four hundred sixty-three to four hundred fifty-seven. His margin was down to six.

He was sweating profusely. Raen ordered a drink for them each, and Jim took a great swallow of his, all the while staring at a blank comer of the room, meeting no one’s eyes.

“These folk do make you uncomfortable,” she said. “But if you win—why, then you’ll be out among them, free and very wealthy. Perhaps wealthier than they. Do you think of that?”

He took yet another drink and gave no answer. Sweat broke and ran at his temple.

“How many games yet remain?” she asked.

“We dock three days from now.”

“With time in the evening for a set?”

He shook his head. This was to his advantage. He still had his lead.

“Twenty games, then.” She glanced at the Istrans, gestured them to seats on opposite sides of her table, between him and her. Their faces blanched. There was rage there, and offence. They came, and sat down. “Do you want to play a round for amusement?” she asked Jim.

“I would rather not,” he said. “I’m superstitious.”

Azi served them, all four. Jim stared at the area of the table between his hands.

“It’s been a long voyage,” Kont’ Raen said. “Yet the society in the salon has been pleasant. What brings you out from Istra and back, seri?”

“Trade,” Kest said.

“Ah.”

“Kontrin—” Merek Eln said. She looked at him. He moistened his lips and shifted his weight in big chair. “Kontrin, there’s been some disturbance on Istra. Matters are still in a state of flux. Doubtless—doubtless you’ve had some report of these affairs.”

She shrugged. “I’ve kept much to myself of late. So trade took you off Istra.”

There was a hesitation, a decision. Merek Eln went pale, wiped at his face. “The need for funds,” he confided. His voice was hardly more than a hoarse whisper. “There has been hardship on Istra. There’s been fighting in some places. Sabotage. One has to be careful about associations. If you’ve brought forces—”

“You expect too much of me,” Kont’ Raen said “I’m here on holiday. That is my profession.”

This was irony even they understood as such.

They said nothing. Kont’ Raen sipped at her drink and finished it. Then she rose and left the table, end Jim excused himself hastily and withdrew among the azi who served.

The thought occurred to him, not for the first time, that Kont’ Raen was simply insane.

He thought that if she gave him the chance now to withdraw from the wager, he would take it, serve the ship to the end of his days, content in his fate.

He lost two points off his margin the next evening. The tally stood at four hundred sixty-seven to four hundred sixty-three.

There was no sleep that night. Tomorrow evening was the last round. No one in the azi quarters offered to speak to him. The others sat apart, as if he had a contagion. It was the same when one approached termination. If he won, they would hate him; if he lost, he would only confirm what they believed, the luck that made them what they were. He crouched on his mat in a corner of the compartment, tucked big knees up to his chin and bowed his head, counting the interminable moments of the final hours.

vi

Jim was at the table early as usual, waiting with the wands and the dice. The Istrans arrived. Other azi served them, while even beta crew arrived in the salon to watch the last games. The whole ship was shut down to skeleton crew, and those necessary posts were linked in by monitor.

Jim looked at the table surface rather than face the stares of free men who owned his contract, who had come to watch the show. They would not own it after this night, one way or the other.

There were light steps in the corridor, toward the door. He looked up, saw Kont’ Raen coming toward him. He rose, of respect, the same ritual as every evening. Azi set drinks on the table, as every evening.

She was seated, and he resumed his chair.

What others did in the room now he neither knew nor cared. She cast the dice for the first throw; he did, and won the right to begin.

He won the first game. She won the next. The sigh of breath was audible all about the salon.

The third game was hers, and the fourth and fifth.

“Rest?” she asked. He wiped at the sweat that gathered on his upper lip and shook his head. He won the sixth and lost the seventh and eighth.

“Four sixty-nine to four sixty-nine,” she said, Her eyes glittered with excitement. She ordered ice, and paused for a drink of water. Jim drained his glass and wiped his face with his chilled hand. The cooling did not seem enough in the salon. People were crowded all about them. He asked for another drink, sipped it.

“Your stakes are greater,” she said. “I cede first throw.”

He accepted the wands. Suddenly he trusted nothing, no generosity of hers. He trusted none present. Of all the bets which had been made on the azi deck, he was sure now how they had been laid. The looks as the Kontrin tore away his lead let that be known…who had bet on him, and who against. Some of those against, he had believed liked him.

He cast. Nothing showed but black and white; he declined and she cast: the same. It was a slow game, careful. At twenty-four he threw a black…chose to play the throw against her thirty-six, and won not only the pair of ships, but also the black, wiping out his score. His bands began to sweat He played more conservatively then, built up his score and declined the next black, dreading black in her hand, which did not show. He reached eighty-eight. She held seventy-two, and swept up a trio of stars to take the ninth game.

It stood at four hundred sixty-nine to four hundred seventy, her favour.

“What do you propose if we tie?” she asked.

“An eleventh game,” he said hoarsely. Only then did it occur to him that he might have proposed cancellation of bets. She nodded, accepting him at his word. He must win tenth to force an eleventh.

She gathered up the wands. The living chitin on the back of her hand shone like jewels. The wands spilled across the table, white, white, white.

Game, for the winner.

She offered him the dice. She led; the courtesy was mandated by the custom of the game. His hand was sweating; he wiped it on his chest, took the dice again, and cast: six.

She took up the cubes for her own turn, threw.

Seven.

“Game,” she said.

There was silence. Then those in the room cheered…save the azi, who faded back, reminded that escape was not for their kind. Jim blinked, and fought for breath. He began to shiver and could not stop.

Kont’ Raen gathered up the wands and, one by one, broke them. Then she leaned back in her chair and slowly finished her drink. Quiet was restored in the room. Officers and azi remembered that they had duties elsewhere. Only the Istran couple remained.

“Out,” she said.

The couple hesitated, indignant, determined for a moment to stand their ground. Then they thought better of it and left. The door closed. Jim stared at the table. An azi never looked directly at anyone.

There was a long silence.

“Finish your drink,” she said. He did so; he had wanted it, and had not known whether he dared. “I thank you,” she said quietly. “You have relieved my boredom, and few have ever done that.”

He looked up at her, suicidal in his mood. He had been pushed far. The same desperation which had kept him from withdrawing from the game still possessed him.

“You could have dropped out,” she reminded him.

“I could have won.”

“Of course.”

He took a last swallow from his glass, mostly icemelt, and set it down. The thought occurred to him again that the Kontrin was quite, quite mad, and that out of whim she might order his termination when they docked. She evidently travelled alone. Perhaps she preferred it that way. He was lost in the motivations of Kontrin. He had been created to serve the ships of Andra Lines. He knew nothing else.

She walked over and took the bottle from the Istrans’ table, examined the label critically and poured again, for him and for her. The incongruity of the action made him sure that she was mad. There should have been fresh glasses, no ice. He winced inwardly, and realised that such concerns now were ridiculous. He drank; she did, in bizarre celebration.

“None of them,” she said, with a shrug at all the empty tables and chairs, the memories of departed passengers, “none of them could dice with a Kontrin. Not one.” She grinned and laughed, and the grin faded to a solemn expression. She lifted the glass to him, ironic salute. “Your contract is already purchased. Ever borne arms?”

He shook his head, appalled. He had never touched a weapon, seldom even seen one.

She laughed and set the glass down.

And rose.

“Come,” she said.

Later, high in the upper decks and the luxury of the Kontrin’s staterooms, it came to what he thought it might.