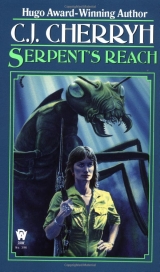

Текст книги "Serpent's Reach"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“There’s men would go,” the young beta insisted. “Farms like ours and big estates too, belly-full with the way ITAK’s run us. There’s men all over would go to settle this once for all, would go with you, Kontrin.”

“No.”

“Sera,” Merry objected. “This is sense he offers.”

“This is the tapes,” she said, looked about at all their faces, azi and beta. “ Tapes…you understand that? You owe me nothing. We taped it into your ancestors seven hundred years ago. All your loyalty, all your fear of us, your desire to obey. It’s ail psych-set. Your azi know where their ideas come from. I’m telling you about yours. You’re following a program. Stop, before it ruins you.”

There was silence, stark silence, and the young man stood stricken and the young woman held her child close.

“Be free,” Raen said. “You’ve your farm. Let the cities go. I doubt there’ll be more azi. These are the last. They’ll go at their forty-year. Have children. Never mind the quotas. Have children, and be done with azi and with us.”

“It’s treason,” the older Ny said.

“We created you; is that a reason to die with us? Outsiders have left the Reach, for a time long in yourterms. The old woman who rules on Cerdin will fall soon, if not already; that they’ve come for me openly says something of that; and there’ll be chaos after. Save what you can. Depend on no one.”

“You stay, then,” said Berden. “You stay with us, sera.”

She looked at the beta in affront, and the gentleness in that woman’s face and voice minded her of old Lia; it hurt. “Tapes,” she said. “Come on, Merry. Load the truck.” She glanced again at the Ny-Berdens. “I’m sorry about taking from you; all I can give you in return is advice. You’ve the lifetime of these azi to prepare yourselves for years without them, for a time when there’ll only be your children to farm the land. And never– nevermeddle with the hives.”

The azi gathered themselves, packed up food and water, headed for the waiting truck. Raen turned her back on the betas, pulled on the sunsuit, took up her rifle again, went out down the steps. Warrior hovered there, clicking with anxiety. Merry was tying on containers of extra fuel, a can and a half. “All we have?” she asked; Merry shrugged. “All, sera. I drained it.”

Already the azi were boarding, all who could come and many who should not, insisting they were guard-azi and not farmers.

For them she felt most grief, for men who could imagine nothing more than to come with her. Even some of the farm azi rose and started forward, as if they thought that they were supposed to come, but she ordered them back, and they did not.

Then Merry climbed aboard, waiting on her. She saw two more waiting…long-faced, and the back of the truck was jammed; she motioned them into the cab, two more that they could manage, for in the back, men sat three deep, rifles leaned where they could; or stood, leaning on the frame. Heat went up from the ground and the truck in waves.

She squeezed herself in with Merry and the two others, pulled the door shut: no air-conditioning…they needed the fuel. There was a last scurrying and scrabbling atop the truck. Warrior was minded to ride for a space, boarded even as Merry put the vehicle in motion and it laboured out, swaying and groaning, toward the dirt road.

“Left,” Raen said when they reached the branching, directing them toward the River, and abandoned depots and the City.

She had the map, on her knee, and the hope that the vehicle would hold together long enough. She looked at Merry, past the two azi who shared the cab with them. Merry’s face was solid and stolid as ever, no sign of dread for what they faced.

How could there be, she wondered, for the likes of them, who knew their own limits, that they were designed and bred for what they did, and did it well?

They had not even the luxury of doubt.

We are outmoded, they and I,she thought, closing her hands about the smooth stock of the rifle. Appropriate, that we go together.

BOOK NINE

i

There was a presence at the door, beyond the sealed steel. Moth did not let it hasten her, carefully poured wine into the crystal with a steady left hand. The right hung useless. It throbbed, and the fingers were too swollen to bend. She did not look at it. The bandages sufficed; the robes covered it; and she deliberately forced herself to move about, ignoring it.

Something hissed at the door. She caught a flicker from the consoles about the room, a sudden shriek of alarm after. She set the wine down quickly and keyed broadcast to the hall outside.

“Stop it,” she snapped. “If you want these systems intact, don’t try it.”

“She’s alive,” she heard in the background.

“Eldest,” an old voice overrode it, a familiar voice. She tried through the haze of pain to place it. Thon. That was Nel Thon. “Eldest, only your friends are here. Open the doors. Please open the doors.”

She said nothing to that.

“Crazy,” someone said farther away. “Her mind has gone.” Someone hissed that voice to silence.

“No,” she answered it. “Quite sane. That you, Nel?”

“Eldest!” the voice overflowed with relief. “Please, open the doors. It’s settled, over with. The forces loyal to you have won. Use the intercomp channels and confirm it for yourself.”

“Loyal to me?” Pain made her voice harsh and she fought to make it even again. “Go back to the hives, Thon. Tell themyour loyalty.”

“Everything is stable, Eldest. Unlock the doors.”

“Go your way, Nel Thon. Lord it in Council without me. Try your own terminals to intercomp. They’ll work…so far.” She drew a deep breath and cared little now how her voice sounded. “That door opens from the inside, cousins. Force it and you’ll trigger a wipe.”

There was a burst of voices from outside. She could not distinguish words.

“Please,” said Nel Thon. “Is there some condition you want? Is there any assurance you want?”

“The same goes,” she continued, “for trying to gain access to the banks, dear cousins. My key is fed in with a destruct order. When I go, it goes. Figure your way around that, cousins.”

There was profound silence outside.

In time a whispering of anguished voices retreated from the area. She left the set on broadcast and settled back again, picked up the goblet and drank, sipped at it slowly, for the wine had to last.

ii

The ship was there, on the field, a sleek, familiar shape too graceful for the ground. Morn took time for a glance, attended to the necessary business of landing: the shuttle was not made for fine manoeuvres.

Touchdown. He ignored the field patterns; tower was dead, and there were no lights to relieve the evening haze. He used the moving gear to take the shuttle up to the rear of the star. ship, out of the track of its armament.

“They answer,” the azi at com told him quietly. “They’re Hald azi and they’re upset.”

“Time they responded,” Morn said. He began shutdown, closed off systems. “Standard procedures.” He looked back through the ship, to the dozen who were with him, armoured and armed. Chatter crackled in his left ear: no port control, but the Istra shuttle coming in with thirty more of his men, hard behind him. “Ask where Pol is.”

“They say,” the com-azi reported back slowly, “that he’s gone into the City some time ago, hunting the Meth-maren face to face. They weren’t told how he’s proceeding, or where.”

“Is Sam with him?” Morn asked, for that one of Pol’s azi was his most reliable.

“No. It’s Sam I’m talking to.”

“Tell him to open that ship” Morn rose, ducking the overhead, felt for his gun and gathered up his sun-kit and his rifle. One-unit readied itself to accompany him.

“Sam says,” the com-azi called after him, “that he doesn’t want to open. He says he’s not sure he should.”

Morn looked at the com-azi, his breath shortened by temper. “Tell Sam he has no choice,” he said, and opened the hatch.

There was a thunder of engines outside, the Istra shuttle coming in. “Have them form up beside this ship,” he directed two-unit leader, and rode the extending ladder down: one-unit was quickly at his heels.

He had a prickling at his nape, being in the open, near the terminal building. Betas might occupy that point, that flat roof, ITAK betas, who were likely hersto a man, and dangerous. He darted glances to all likely points for snipers, and half-ran the space to Pol’s sleek Moriah, careless of dignity. Sam was capitulating, lowering the ramp, having come to his senses.

He climbed it with half hid escort, stood inside, breathing the cold air of the hatchway. Pol’s whole staff gathered there, Sam prominent among them, a sandy-haired azi with a scar at his brow.

“Out of my way,” Morn said, and elbowed Sam aside; the others moved, pushed aside by his armoured escort. He walked into controls with Sam anxiously struggling his way through after—sat down and read through what there was to read.

There was nothing. He turned around, a frown gathered on his face. “Sam. What kind of operation has he out there? What force is with him?”

The azi ducked his head in distress. “Alone, ser. He went alone.”

Morn drew in his breath, eyes flicking over the staff of Moriah, finding them far too many: it was likely truth. Guard-azi. Dark-haired Hana, a female azi who was Pol’s eccentricity, not even particularly beautiful. Tim, like Sam, Pol’s accustomed shadow.

“Where,” Morn asked, “is the Meth-maren based? City? ITAK Central?”

“We don’t know.”

It was truth. Sam was distressed; the whole staff was distraught.

“Stay and hold this ship,” Morn directed his own men. “If Pol shows up, tell him to stay here.”

A stiffing feeling of things wrong assailed him. He thrust his way past them, out, down the ramp again where the other half of one-unit waited. The second shuttle had disgorged its occupants. Thirty more men waited orders.

A long partnership, his with Pol: forty years. They had shared much, had hunted together—and not only in sport. He tolerated Pol’s humour and Pol supported his grimmer amusements.

Pol’s humour. He looked about him, at dead buildings, at a sky void of traffic, the only sound that of the wind tugging at cloth and the popping of cooling metal. It was not a time or place for an exercise of whim, not even Pol’s.

He had sent Pol, in advance of the order which sent him: Pol’s humour, to ask this of him.

Pol…who avoided Cerdin of late; who avoided many old connections, and the hold at Ahlvillon—and, avowing her tedious… Moth.

He paused, hard-breathing, looking back at Moriah, Pol avowed he had no sense of humour. Pol contrived, finally, to disturb his self-possession.

He shouted an order to the azi, stalked off toward the buildings of the terminal. Azi hastened to cluster themselves about him, shielding him with their armour and their bodies; he took this for granted, it being their function, and himself conspicuous for the Colour that he wore.

Sun’s glare still reflected off windows, but there was more than one window missing, betokening more than a quiet power shutdown here. That drew him, promising some insight into what had happened in the City.

And in the terminal, scattered over the polished floors, there were dead, male and female, young and old.

With live majat.

“Don’t fire!” Morn snapped. One stepped lightly toward them, in the doorway. He saw the badges on it: it was a red, that had never been trouble for Hald.

“Kontrin,” it moaned, when he held up his fist. “Green-hive.”

“Held. Morn a Ren hant Hald.”

Palps swept forward. “Hhhhald. Friend. Giffftss.”

The tone of that chilled the flesh. But one took allies where one could, when family faded. “I’ll settle with the Meth-maren for you. I need to locate her base. Her-hive. Understand?”

“Yes. Understand.” It shifted forward, and the azi flinched, torn between terror and duty. It extended a forelimb, touched at his chest, and he suffered it, concealing his loathing, reckoning he might have to accept worse than this. “Red-hive knows Meth-maren hive, yes. Blues guard. This-unit will call othersss, many, many, many Warriors, reds, golds, greens, all move. Come kill, yess.”

“Yes,” he confirmed—did not touch it; that risk was one he did not choose to run, and the Warrior did not offer.

Others moved, to a shrilling command only partially in human hearing. They gathered, out of all the recesses of the terminal, a living sea of chitinous bodies.

“Tunnels,” the Warrior said. “Tunnels for beta-machines. Ssubwayss.”

iii

The house stirred and hummed with activity. One could hear it, even in the upper floors, the stir of many feet, the singing of majat voices. Jim sat still in the semi-dark beneath the dome, on the bed, hands loose over his crossed legs, watching the Kontrin who slumped angrily in the chair opposite. They were at a silence, and Jim found that profound relief, for Pol Hald reasoned well, and wounded accurately when he wanted to.

The power was gone, had been for hours; he believed now that it would not return.

There’s no more comp,Pol had advised him. Nothing. If you’d listened earlier, something might have been done. Something still might. Listen to me.

Jim gave no answers. He could not argue with such a fluency: he could only steadfastly refuse. Max, downstairs, gave him the means to refuse. Warrior, standing faithfully outside, was a guard against which even Pol Hald’s reasoning could not prevail.

Newhope’s dead,Pol had said. There’s nothing here for her. Only trouble. He’s here. Morn’s here. He’ll be coming, and she’ll know that.

He could not listen to such logic. It made sense.

Below, the majat swarmed and stirred and tugged at foundations.

And in the dome above, the stars began to show in a darkening sky, the majat song to swell louder.

“Does it never stop?” Pol demanded.

Jim shook his head. “Rarely.”

Pol hurled himself suddenly to his feet. Jim rose, alarmed. “Relax,” Pol said. “I’m tired of sitting.”

“Sit down,” Jim said, received of Pol a cold and sarcastic look. There was a certain incongruity in the situation.

And abruptly the song fragmented to a shrilling note.

Outside, Warrior dived for the stairs, scuttled away. “Come back!” Jim shouted at it, and jerked from his pocket the gun which he had for his protection, an azi against a Kontrin. Pol saw it, raised both hands and turned his face aside, miming peace.

Jim held the gun in both hands to steady it. “Max!” he shouted, panic hammering in him.

“Please,” Pol said fervently. “I’d not be shot by mistake.”

Steps tramped up the stairs, not human ones, but spurred feet which caught on the carpet fiber, with the hollow gasp of majat breathing. Warrior loomed up in the doorway again.

“Many, many,” it announced. “Trouble.”

Jim did not take his eyes off Pol-motioned nervously with the gun, indicated the chair. Pol subsided, his gaunt face anxious.

“Where’s Max?” Jim asked of Warrior.

“Down. All down in outside. Warrior-azi, yess. Much danger. Reds, golds, greens are grouping. Blues are here, Jim-unit. Kill this green, take taste to Mother, yesss.”

Pol looked for once sober, his hands held in plain sight. “Argue with it, azi.”

“Stay still!” Jim tried to control his breathing, tried to reason. “I hold this place,” he said. “No, Warrior. This is Raen’s. She’ll understand it when she comes.”

“Queen.” Warrior seemed to accept that logic. “Where? Where is Meth-maren queen, Jim?”

“I don’t know.”

Warrior clicked to itself, edged forward. “Mother wants. Mother sends Warriors out, seek, seek, find. I guard. This-chamber is no good, too high. Come, this-unit guides, down, down, where safety is, good places, deep.”

“No,” Pol advised softly, alarm in his voice.

“I trust Warrior more. Up, ser. Up. We’re going downstairs.”

Pol made a gesture of exasperation and rose, and this sudden lack of seriousness in him, Jim watched with the greatest apprehension. Pol sauntered out, past him, and Warrior led them downstairs, Jim last and with the gun at Pol’s back.

The center of the house, windowless, was plunged in darkness, blue lights bobbing and flaring on the walls and making strange shadows of their bearers. Majat-azi skipped about them, touching them, Pol as well. The Kontrin cursed them from him, and they laughed and scampered off, taking the light with them.

Other azi remained, in the blackness. “Jim,” Max’s voice said. “They urged us to come in. Was it right to do? I thought maybe we shouldn’t, but they pushed us and kept pushing.”

“You did right,” Jim said, although in his mind was the horrible possibility of being swept up with the majat-azi, herded deep below. “The Hald is with us. Watch him.”

“Tape-fed obstinance,” Pol’s voice came, outraged, for they laid hands on him. “If you would listen—”

“I won’t.”

“At least check comp.”

Jim hesitated. It ceased to be an attempt to unsettle him, began to seem plain advice. He felt his way aside, into the comp centre, shuddered as a majat-azi brushed his shoulder. He caught a slim female arm. “Stay, come,” he asked of her, for the light’s sake, and took her with him, into the face of the dead machinery, the dark screens.

But paper had fed out, printout, in the machine’s dying.

He was stricken, suddenly, with the realisation Pol had been urging him to what he should have done. He drew the majat-azi to the machine, tore off the print and laid it on the counter. “Light,” he said, “light,” and she lent it, leaning on his shoulder with her arm about him. He ignored her and ran through the messages as rapidly as he could read the dim print in azi-light. Most were of no meaning to him; he had known so. Pol might understand, and he knew that Pol would urge him to show them to him: but he dared not, would not. It was useless; the key to these was not in the tapes he had stolen.

JIM, one said plainly. STAND BY. EMERGENCY.

It was not signed. But only one who knew his name could have used a comp board.

Sent before her trouble, perhaps; the possibility hit his stomach like a blow, that she had needed him, and he had been upstairs, unhearing.

“Stay!” he begged of the azi, who had tired of what she did not understand. He caught at her wrist and held her light still upon the paper, ran his eye over the other messages.

JIM, the last said, BEWARE POL HALD.

He thought to check the time of transmission; it was not on this one, but on the one before…an ITAK message… One in the night and one in the morning.

He looked up, at a commotion in the doorway, where dancing azi-lights cast Pol Hald and Max and others into a flickering blue visibility.

Alive,his heart beat in him. Alive, alive, alive.

And they had let Pol in.

“Is it from her?” Pol asked. “Is it from her?”

“Max, get him down to the basement.”

Pol resisted; there were azi enough to hold him, though they had trouble moving him. “Please;” Jim said sharply, rolling up the precious message, and the struggle ceased. He felt the insistent hands of the majat-azi touching him, wanting something of him. He ignored her, for she was mad. “Please go,” he asked of the Kontrin. “Her orders, yes. This house is still hers.”

Pol went then, led by the guard-azi. Jim stood still in the dark, conscious of others who remained, majat shapes. All through the house bodies moved, and round about it, a never-ceasing stream.

“Warrior,” Jim asked, “Warrior? Raen’s alive. She sent a message through the comp before it died. Do you understand?”

“Yess.” A shadow scuttled forward. “Kethiuy-queen. Where?”

“I don’t know. I don’t know that But she’ll come.” He looked about him at the shapes in the dark, that flowed steadily toward the front doors. “Where are they going?”

“Tunnels,” Warrior answered. “Human-hive tunnels. Reds are moving to attack; golds, greens, all move, seek here, seek Kethiuy-queen. We fight in tunnels.”

“They’re coming up the subway,” Jim breathed.

“Yes. From port. Kontrin leads, green-hive: we taste this presence in reds. This-hive and blue-hive now touch; tunnel is finished. All come. Fight.” It sucked air, reached for him, touched nervously and uncertainly he sought to calm it, but Warrior would have none of it. It clicked its jaws and moved on, joining the dark stream of others that flowed toward the doors.

Azi went, majat-azi, bearing blue lights in one hand and weapons in the other, naked and wild. Warriors hastened them on. Jim tried to pass them, almost gathered up in their number, but that he ducked and went the other way, down the hall and down the stairs.

Blue azi-lights were there, hanging from majat fibre, and a draft breathed out of an earth-rimmed pit, the floor much trampled with muddy feet. Max and the other azi were there in a recess by the stairs. and Pol Hald among them.

Pol rose to his feet, looking up at him on the stairs. Azi surrounded him with weapons. “There’s nothing,” Pol said, “so dangerous as one who thinks he knows what he’s doing. If you had checked comp while it was still alive—when I told you to—you could have contacted her and been of some use.”

That was true, and it struck home. “Yes,” he admitted freely.

“Still,” Pol said, “I could help her.”

He shook his head. “No, ser. I won’t listen.” He sank down where he stood, on the steps. At the bottom a majat-azi huddled, a wretched thing, female, whose hands were torn and bleeding and whose tangled hair and naked body were equally muddied. It was uncommon: never had he seen one so undone. The azi’s sides heaved. She seemed ill. Perhaps her termination was on her, for she was not young.

“See to her,” he told one of the guard-azi. The man tried; others slid, and the woman would take a little water, but sank down again.

And suddenly it occurred to him that it was much quieter than it had been, the house silent; that of all the Workers which had laboured hereabouts—not one remained.

The tunnel breathed at them, a breath neither warm nor cold, but damp. And from deep within it, came a humming that was very far and strange.

“Max,” Jim said hoarsely. “They’ve gone for the subways of the city. A red force is coming this way.”

Pol sank down with a shake of his head and a deep-voiced curse.

Jim tucked his arms about his knees and wished to go to that null place that had always been there, that he saw some of the guard-azi attain, waiting orders. He could not find it now. Tape-thoughts ran and cycled endlessly, questions open and without neat answers.

He stared at Max and at the Kontrin, at the Kontrin most of all, for in those dark and angry eyes was a mutual understanding. It became quieter finally, that glance, as if some recognition passed between them.

“If you’ve her mind-set,” Pol said, “use it. We’re sitting in the most dangerous place in the city.”

He looked into the dark and answered out of that mindset, consciously. “The hive,” he said, “is safety.”

Pol’s retort was short and bitter.

iv

Itavvy rose and walked to the door, walked back again and looked at his wife Velin as the infant squirmed and fretted in her arms, taxing her strength. One of the Upcoast women offered a diversion, an attempt to distract the child from her tears. Meris screamed in exhausted misery…hunger. The azi outside the glass, with their guns, their faceless sameness, maintained their watch.

“I’ll ask again,” Itavvy said.

“Don’t,” Velin pleaded.

“They don’t have anger. It isn’t in them. There are ways to reason past them. I’ve dealt—” He stopped, remembered his identity as Merck Sod, who knew little of azi, swallowed convulsively.

“Let me.” The gangling young Upcoaster who had spent his time in the corner, sketch-pad on his knee, left his work lying and went to the door, rapped on it.

The azi ignored it. The young artist pushed the door open; rifles immediately lowered at him. “The child’s sick,” the youth said. “She needs milk. Food. Something.”

The azi stood with their guns aimed at him…confused, Itavvy thought, in an access of tension. Presented with crisis. Well-done.

“If you’d call the kitchens,” the artist said, “someone would bring food up.”

Meris kept crying. The azi hesitated. unnerved, swung the rifle in that direction. Itavvy’s heart jumped.

Azi can’t understand, he realised. No children. No tears.

He edged between, facing the rifle. “Please,” he said to the masked face. “She’ll be quiet if she’s fed.”

The azi moved, lifted the rifle, closed the door forcefully. Itavvy shut his eyes, swallowed hard at nausea. The young artist turned, seta hand on his shoulder.

“Sit down,” the youth said. “Sit down, ser. Try to quiet her.”

He did so. Meris exhausted herself, fell whimpering into sleep. Velin lifted bruised eyes and held her fast.

Then, finally, an azi in ISPAK uniform brought a tray to the door, handed it in, under guard.

Drink, sandwiches, dried fruit. Meris fretted and ceased, given the comfort of a full belly. Itavvy sat and ate because it was something to do.

The identity of Merek Sed would collapse. They were being detained because someone was running checks. Perhaps it had already been proven false. They would die.

Meris too. The azi had no feeling of difference.

He dropped his head into his hands and wept.

v

The truck laboured, ground up the slope from the riverbed, picking up dry road in the headlights. Raen threw it to idle at the crest, let what men had gotten off climb on again, the truck pinking on its suspension as it accepted its burden. She read the fuel gauge and the odometer, cast a look at Merry, who opened the door to look out on his side. “They’re all aboard,” he said.

“Then go back to sleep.” She said it for him and the two azi crowded in between them, and eased the truck forward, walking it over ruts that jolted it insanely and wrenched at her sore arms. A thousand kilometres. That was one thing on the map, and quite another as Istrans built roads. The track was only as wide as the truck. The headlights showed ruts and stones, man-high grass on either side of the road, obscuring all view.

A nightmare shape danced. into the lights before them, left again: Warrior stayed with them, but the jolting on this stretch was such that it chose to go on its own feet.

By the map, this was the only road. They were on the last of their fuel, that which they had brought in containers, having used the stored power and both main and reserve tanks. They might nurse a kilometre back out of batteries after the fuel ran out. Cab light went on. Merry was checking the map again, counting with his fingers and making obvious conclusions.

“It’s six hundred to go,” Raen said, “and it pulls too much. We’re loaded way beyond limits and we’re not going to do it.”

“Map shows good road past the depot.”

“Easier walking, then.” Raen looked to the side as a black body hit the door, scraped and scrambled its way to the roof of the truck. Warrior had decided to ride again. Six hundred kilometres more: easy on a good road with an unburdened truck. As exhausted men would walk it…days.

“Could be fuel there,” Merry offered.

“One hopes. If we get that far.”

“I’ll drive again, sera.”

“We’ll change over at the depot. Rest.”

Merry turned the light out. He did not seem to sleep, but he said nothing, and in him, in the two with them—likely in all those men in the rear—there was evident that familiar blankness. They lost themselves in that, and perhaps found refuge.

She had no such. There was a stitch in her back which had been growing worse over the hours, and fighting the steering aggravated it; the right shoulder ached, until finally she chose to let the right hand rest in her lap, however much that tired the left. The jolt of the crash, she reckoned. Pain was something she had long since learned to ignore. A stoppered bottle sat beside her; she moved the right hand to it, flipped the cap with her thumb, took a drink of water, capped it again. It helped keep her awake. She worked a bit of dried fruit from her pocket, bit off a little and sucked at that: the sugar helped too.

The road worsened again, after a little smoothness; she applied both hands for the while, relaxed again when it passed. Imagination constructed a picture of the men in the back, jammed in so that some must constantly stand, or lie on others, whose muscles must cramp and joints stiffen, all jolted cruelly with every hole she could not avoid and every lean and lurch of the turns.

Figures flicked past on the odometer, a red pulse far too slow. The fuel registered lower and lower, most gone now out of the last filling.

Then the road smoothed out on a fiat high enough to see no flooding. She kicked them up to a better pace, and Merry came out of his trance and shifted position, causing the other two men to do the same.

“Should be coming up on the depot,” she said.

Merry leaned to take a look at the fuel and said nothing.

There was a scraping overhead. A spiny limb extended itself over the windshield. Warrior slid partially down, and Raen swore at that, for they had no margin for delays. It gaped at the glass, insisting on her attention, and at the realisation it was urgent her heart began to beat the faster.

She let off the accelerator, coasted, rolled down the window lefthanded. Warrior scrambled off when they slowed enough, paced them, the while the headlights picked out only dusty ruts and high weeds.

“Others,” Warrior breathed. “Hear? Hear?”

She could not. She braked, threw the engine to idle, quieter.

“Many,” Warrior said. “All around us.”

“The depot,” Merry said hoarsely. “They’ve got it.” Raen nodded, a sinking feeling in her stomach.

“Get the men out,” she said. “They’d better limber up, be ready for it, be ready to dive back in on an instant. Third thorax ring, centre; or top collar-ring, if they don’t know. Make sure they understand where it counts.”

Merry bailed out, staggering, felt his way around to the back. Warrior was dancing in impatience beside the truck. The two men in the cab edged out and followed Merry.

“How far?” Raen asked. Warrior quivered very rapidly. Near, then. She felt the truck lighten of its load, eased off the brake and set it in gear, not to waste precious fuel. Merry’s door was open. She left it so; he might need it in a hurry. “Warrior—hear me: you must not fight. You’re a messenger. Understand?”

“Yess.” It accepted this. It was majat strategy. No heroism, she thought suddenly, not among majat: only function and common sense, expediency to the limit. Warrior was very dangerous at the moment, excited. It paced the slow-moving truck as the men did. “Give message.”