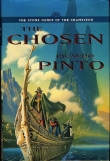

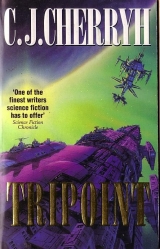

Текст книги "Tripoint "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Marie keyed up another file in the Financial Access section, downloaded it… they said a ship at Viking Free Port had open access to the trade records. Translation: they let you look. If you understood the software and knew what files might be significant, good luck, you had a chance, but the too-damned-helpful system wanted to pre-digest the reports for you if you got into the market area, not give you access to the raw data, and thatwas a piece of computer cheek.

So Corinthianhad pulled out. Spooked out, left, maybe to change its whole pattern, her worst fear, and she was not in a mood to be lectured to by Family.

Maybe, with luck, and substantial evidence, she could get the cops into Miller's warehouse.

"Marie."

"I'm not deaf." The station files were in database and wouldn't be accessed from Sprite's ops boards, the Rules were against it. Unfortunately so was the barrier system. So one trekked in and asked questions, and even load-splicing couldn't fit the total DB onto any data storage medium that the casual questioner might carry into the Trade Bureau.

"Mischa's been worried."

"I don't know why." Another splice. Another capture. Hours to reconstruct the bastard when she got it home.

"He's not happy about the fines, Marie."

"I imagine not. Sorry about that. We'll make it up."

"You're due back to handle offloading."

"Charles can do it. He's perfectly competent."

"What are you doing?"

"Trade information. Data. What else is the Trade Bureau for?"

"Fine. Fine. I'll tell him.—Tell Tom get his rear back on duty. You don't need him here."

Saja was Tom's officer, on the bridge. Saja had reason to ask.

Saja had actual need-to-know where Tom was. And should, by now. She turned away from the monitor and looked at him straight-on, with the least disturbed inkling of things not quite in order.

"He's not with me," she said. "Have the cops got him?"

"The cops didn't arrest anybody, either side. He's not with you. He's not on the ship. I called them five minutes ago, max."

Wandering around the docks looking for her. "The damned fool," she said.

"That ship's out of dock, Marie. It's outbound."

She knew where the ship was. She looked at the clock on the wall of the Trade Bureau. Hours out. Computers ate up human time—you lost track between keystrokes and during processing.

And Saja was saying Tom could be withthat ship?

She didn't think so. "He's not that stupid. He's searching the bars, is where he is."

"We've got people all over the bars. We're looking. For you. And for Tom. You're accounted for. Where's Tom?"

"Wherever he thinks I'd go. Bars. Sleepovers.—Miller Transship." She didn't want to suggest that last name. She didn't want them forewarned. But—" Corinthian'sbroker. Miller Transship. Warehouses. Phone Sprite-com, get them to inquire at Miller's, just down the row from Corinthian'sberth."

"Miller's," Saja said, and went, she supposed, for a phone.

They just weren't searching right. Tom was going to duck them. The kid was no fool.

But the more they stamped around searching for the damn kid, disturbing evidence…

Most urgently, they needed to find the damn kid and quit stirring things up, before he or they did do something stupid.

She was uneasy. Couldn't really remember where she was in the data problem. Damn the brat, he'd always had a knack for disturbing her concentration.

And Tom probably wasstaying out of reach and deliberately out of touch with Spritesimply because he thought shewas staying out of touch (true, until now) and he was looking for her. It could take a while to reel him in.

Though you'd think once Corinthianhad gone on the board for Departure, the kid would catch a notion that the game was up at that point, retreat, call Spriteand report in… since she, at that point, had no more reason to stay under-surface.

Damn.

He wouldshow up. He hadto show up. She didn't want to leave her search looking for an erratic, jump-at-shadows brat who was old enough to take care of himself.

She jabbed a key, dumped the current operation, pocketed her data-cards on the way to the door, and swore to kill the kid when she found him.

—ii—

TOM STARED AT THE CEILING, feeling the push on the ship and thinking how if he'd had the presence of mind to have counted when the shove started he could have told something about the actual v, based on the undock pattern.

But what did it matter? Corinthianwas going and he was going with it,

No way Spritecould throw over that government contract to chase after him. Not even Marie could talk them into it.

Only hope to God that Mischa's fears were exaggerated and Corinthianwasn't going to lay for Spriteout in the dark.

Out in the same dark, a body could go out the airlock and never be reported, if his own biological father wanted to get rid of him. And what paternal interest had Austin Bowe ever needed in the offspring he'd probably… spacer-fashion… scattered on God-knew-what ships? Men didn't generally keep up with their own. They had their own ship-board nieces and nephews, if they had sisters. And always they had cousins. Men didn't have to give a damn. And Bowe hadn't a reputation for fatherly concern. The Bowe he'd heard about couldthrow a man out the airlock.

Better than some ways to go, he thought in morbid self-persuasion, while the ship ripped along toward that deep cold. The absolute zero was supposed to get you before you felt much. You froze solid before you could get a breath of vacuum. You frosted your lungs. Your eyes froze and your blood froze and you'd be floating with the dust, exactly the way your outbound breath had left you—until some star near enough went nova and you got shoved along on the wavefront and included in the infall of a next-generation star.

Or none might be near enough and you'd just drift there till entropy slowed down the stars for good.

A permanent sort of half-life, as it were.

Permanent as the galaxy. No damn fathersto deal with.

Father, hell! There had to be a word for a guy with as little invested as Austin Bowe.

Rapist talked about his relations with the mother in question. Society hadn't made a word for his relations with the kid that resulted.

Hadn't made a word for the situation between them or given him a word he wanted to say to Austin Bowe.

Thanks for screwing my mother? Thanks for not showing up till now. Screw you, sir, for a damned self-centered son of a bitch.

Acceleration was steady at +2or thereabouts. The straps would hold against five and six times that. He'd no fear of them giving way. But Corinthianspent energy like it was handed out free, and he measured his breaths, feeling the anger of a ship forced out of port, maybe out of civilization altogether.

Or—remotely possible, if Marie had found her evidence—and his heart picked up a beat—they could have the military on their tail.

Which wasn't good news, to think of it. Go up in a fireball, they would, then, and good-bye Tom Hawkins.

It was a nightmare. He didn't know where it had started, whether he'd been in it all his life and this turn of things was someone else's doing, or whether he was that abysmally stupid he'd let himself in for it, going into that warehouse and caring about Marie.

He didn't want to think about reasons. He'd never got it straight about caring for people. His aunt Lydia who'd studied psych had told him when he was five he was emotionally deprived and he never would be normal. So he figured he had to copy, because he was different enough, and he figured he'd better pick good people to copy, like his nursery-mates, sometimes, like Marie sometimes, when he was living with her. Like Saja, again, when he got to know Saja. Mischa…

Definitely not Mischa.

Saja was all right. People liked Saja. But Saja wasn't stupid.

Saja wouldn't have gotten into it. Even if he cared what happened to Marie. And he didn't think it was Marie's fault, him being in the warehouse, he couldn't blame that on her.

He couldn't tell why things happened, most of the time. He certainly couldn't figure this one. He didn't know as much as most people. He'd always figured in the scales of the universe he'd somehow come a little short of what ordinary people got, and not known a lot of things ordinary people knew. It wasn't not knowing his father. A lot of people didn't know that. It was not knowing other things. It was like so damn many contrary signals from Marie and from aunt Lydia and Mischa and them changing their stories all the time, and the fact nobody else liked him much, of his agemates. There was just something wrong, there was something he'd missed, and getting snatched away from Spritelike that, and never seeing anybody again, it was just one more ripping away of information he couldn't get now. He wasn't going back, nobody could get back to their ship unless they were on the same route… he'd accumulate station-debt waiting, even if Bowe let him go finally back at Viking; and he wasn't honestly sure Mischa would spend the ship-account to get him out of hock.

Marie would. Marie was rich in ship-account.

But maybe Marie wouldn't want him at all, then, except to get information about Bowe. Maybe she'd call him a fool and say she didn't know why she'd bought him back… he could hear her tone of voice, as if she were talking to him right now.

But when he imagined Marie yelling at him about being a fool, about going in the warehouse, it sort of put things in perspective, as if now he knew what he'd done, and where he'd been stupid, trying to intervene in Marie's business. The law of the universe was, Marie knew what she was doing, and you didn't put your hands into it or you risked your fingers. Thatwas the mistake he'd made.

So he did understand. And the universe had a little more solid shape around him.

But he decided then, calmly, that he did want to meet Austin

Bowe after all—at least to see the man and know whether they looked alike, or what Marie had seen staring back at her all these years. That would tell him something, too, about the way of things. And that information was on this ship. That was something he could learn about himself. He could listen to Bowe. He could find out the man's habits and figure out if there was anything genetic that just somehow he'd gotten, in the way of temperament, or whatever else could get through the sieve of genetic code.

Marie said… your father's temper. Marie said… your father's manners. Your father's behavior… And he triedto cure it in himself, he tried not to lose his temper and he tried not to be rude, and all the other things Marie attributed to his genes.

Aunt Lydia said most people could pattern themselves off positives. He learned to avoid negatives. Aunt Lydia said he had to define himself, by himself.

And most of all… not do things that pushed Marie's buttons.

But maybe—it was a dangerous, undermining thought, and he worked all around it for a moment—maybe, even remotely possibly… there might even be another side to Austin Bowe. Maybe Marie'd pushed hisbuttons, the way she had other people's, and things had just blown up.

Not to excuse what happened. Nothing could do that.

But maybe what she'd told Mischa and what Mischa had told her might have confused the facts.

And he didn't know why Marie should have gotten the entire truth from Mischa. Henever had.

And… more and more dangerous a thought… if there was another side, considering the position he was in, it did make sense to ask Bowe's side of things. And even if it was bad… and even if he couldn't accept it… considering he was stuck here, considering he had somehow to get along with this crew…

Such as they were.

… he'd learned what happened when you (Lydia's saying) poisoned the water you had to drink from.

He didn't know where this ship went. The rumor-mongering They who ran rampant on Spritesaid it didn't stay on the charts, that it found Mazianni ports somewhere in the great dark Forever.

He could handle that, he supposed. If all Corinthiandid was trade with them, he could justify that… after all, nobody had a guarantee the goods that Spritebrought to port didn't end up being cheated over and run through illegal channels. They weren't responsible. It wasn't immoral. Illegal, highly, but it wasn't like they were doing anything that cost any lives…

He began to sink slowly into the mattress surface. That was the passenger ring engaging as Corinthianwent inertial at its outbound velocity.

A vfar more than most merchanters handled. Light-mass cargo, he thought, staring bleakly at the sound-baffling overhead. Had to be light mass, relative to the engine cap. You wondered what they were hauling.

Luxuries was the commonest low-mass article. Food-stuffs that wouldn't compress. But generally, Viking exported high-mass items, so you hauled heavy, and took the light stuff for—

A siren blew three short bursts. Disaster? he wondered, taking a grip. His heart had skipped a beat. His thoughts went skittering over every horizon, leaving nothing but the wide dark, and the cosmic chance of a high-energy rock in their path.

Then over com, a woman's voice, accented with a ship-speak he didn't recognize.

"We are inertial for the duration, in count for departure. Count now is… sixty seconds, mark."

His heart found the missed beat, thudded along in heavy anticipation. It was real. They were going. He reached for the panel with the white diamond, got the drug out, the needle-pack—shivering-scared, until he had that in his fist. If you didn't have that you didn't come out of jump whole, you left pieces of yourself… that was what the universal They also said, and if you were curious on that topic… they had wards on certain stations where they sent the kids that experimented with hyperspace, and the unlucky working spacers that for some emergency or another hadn't had a pack in reach.

"… count is twenty and running."

He had it. He had it. He was all right, as all right ran, on this ship.

".. . fifteen."

He thought about Marie. He thought he loved her.

(He didn't, really, but Lydia said he wasn't going to be capable of it, yet. Like the prince in the fairy story, he was going to be crazy until somebody loved him… )

But if he had loved anybody it was Marie, and he hadn't loved anybody, if not her, and right now the place where Marie ought to fit—felt like a twisty hollow spot, filled up with anger and hurt where she'd lied to him and ducked out on him, and absolute terror that he'd never see her again and never know what had happened to her.

Because Marie was the edges of the universe. Marie was right and wrong. Marie was the place to go to for the answers and he didn't have a map without her.

Lydia'd say that wasn't normal either. But it was all he had. And nobody else was going to get him out of this. Nobody else gave a damn.

Lydia didn't. Lydia said he was a misfit and a time bomb on the ship. Lydia'd said he'd go off the edge someday, and they ought to find him a nice safe berth on a station, where he could get adopted.

He had nightmares about Lydia finding ways to leave him. Like Lydia convincing Mischa, who didn't like him anyway. And when Marie would send him back to the nursery because she was sick of him, and when the nursery would complain that he was too old, he hurt the younger kids and he wouldn't take their sleep cycle, because all the other kids and all the mothers except Marie were on mainday…

And the nursery workers all wanted to watch vids while the kids were asleep, but they wouldn't let him watch the ones they did, they said go to bed, go to sleep, if he just behaved himself Marie might take him back…

The siren sounded again. Warning of jump imminent.

"Count is five… four… "

He squeezed the pack. Felt the sting of the needle.

"… three… two… "

Marie wasn't coming, wasn't ever coming to get him, where he was going.

—iii—

THE WAVEFRONT OF CORINTHIAN'Spassage was still coming at them when the clock on Sprite'sbridge said to anybody who knew anything that Corinthianhad just left the system.

That information hit Marie in the gut—for God knew what reason, because, dammit, she didn't owe the kid. It was the other way around. Highly, the other way around. She'd searched up and down the frontage where she'd left him, she'd gone back to Spriteto pursue matters as far as she dared with the police, almost to the point of getting swept up and detained herself. It hadn't been a good experience, and meanwhile Spritecrew wholesale was still out searching every nook in every bar and shop they could think of for a damned elusive twenty-three-year-old offspring who ought occasionally to read the schedule boards.

Miller Transship claimed to know nothing. The station police called station Central, and Central called the stationmaster, who called Corinthianlong-distance, himself, big deal, while Corinthianwas outbound.

Surprise: Corinthiandenied all knowledge of Hawkins personnel aboard.

Then Corinthiansaid, which they needn't have said… that if they should turn out to have a stowaway, they'd drop him at their next port.

The stationmaster said, all mealy-mouthed, Do that, and signed off.

Injustice… there wasn't a choice about it. There wasn't a ship in hell or Viking system that could chase that bastard down once they'd finally roused the stationmaster with word something could be wrong… even Sprite, mostly empty. Couldn't, with the head start he'd have had, and their tanks still drawing… and for a station to call an outbound ship to dump vand limp back the long slow days it would take to reach station from where they were, plus buck the outbound traffic, against all regulation… meant big lawsuits if station couldn't prove their case; and catch-me-if-you-can if the merchanter in question wanted to claim they were in progress for jump and missed the transmission. By the time they got back again, witnesses had scattered and it was, again, better have good evidence and a good reason.

So they had to watch the son of a bitch become a blip on station scopes.

And that last, that unnecessary bit of information about stowaways, was a clear message from Bowe, damn his smug face– sheknew. They could just as well pull in the search teams, Tom wason that ship, Bowe had taken away the only thing she had of his, and the remark about dropping Tom 'at their next port' was a threat, not a reassurance. God knew what their 'next port' was, if it wasn't some Mazianni carrier in want of personnel.

If there'd just been proof to give the police, if there'd been any concrete evidence of a kidnapping…

But what could they have done? If she got the evidence now, the station administration could bar Corinthianfrom coming back—supposing the evidence was iron-clad. But it wouldn't be. It was all circumstantial. If the station needed their commerce more than they needed justice done…

But Viking was just newly a free port. Viking didn't want any dirty, unfathomable merchanter quarrel on its shiny new trade treaty. Spritewas from one side of the Line. Corinthianwas from another. The next time Corinthiandocked, was Viking going to search Corinthianfor personnel Corinthianhad plainly just told the stationmaster wasn't going to be aboard next time?

"It's gone," Mischa said with a shrug of his shoulders. "Nothing we can do."

Nothing we can do.

Nothing we can bloody do.

A sanctimonious shrug from Mischa, who'd been watching the clock—and was damned well satisfied to wash his hands of Tom Bowe-Hawkins.

"Nothing we can do," she echoed him. "You son of a bitch, you mealy-mouthed, self-serving son of a bitch, you knowhe's on that ship!"

"That's far from certain, Marie."

"Oh, nothing's ever absolute with you, nothing's ever just quite clear, is it?"

"Marie. This is the bridge. You're on the bridge. Control it, can we?"

"'Control it, can we?' 'Control it?' 'Just shut up, Marie? We know you're not quite stable, Marie? Too bad about your kid, Marie, you can get another one? Why don't you go get laid, Marie, and cure your Problem while you're at it, Marie!"

"Reel it in, Marie, you never gave a damn about that boy!"

"I never gave a damn? Oh, let's talk about giving a damn, Mischa, excuse me, captainHawkins. They could sell him to the Fleet for all we know—they're always short of personnel, he's a good-looking kid, and we know what happens to good-looking kids they get their hands on, don't we, captain Hawkins?"

"We don't even know he's not on dockside. Let's talk about ducking orders, let's talk about kiting off on your own, why don't we? The kid had orders to keep up with you and keep in touch. He violated those orders or we wouldn't be asking where he is right now."

"Oh, now it's hisfault! Everything's someone else's fault."

"Fault never lands in your lap, does it? You ditched your tag, Marie. I'd have thought you'd have learned your lesson twenty years ago."

"Damn your interference! If I hadn't had to dodge you, I'd have the evidence on that son of a bitch, we'd have him screwed with the port authority and Tom wouldn't be in Bowe's ship right now!"

"There is nothing we can do, Marie."

"There was nothing you could do on Mariner, either, was there? I know what it feels like, Mischa, I know, and I don't take 'nothing we can do. ' That son of a bitch is laughing at us, he's laughingat us, do you hear? Or do you give a damn?"

"Marie,—"

"Marie, Marie, Marie! We know his vector, I know that ship, I know what his elapsed-time is like, he's going for Tripoint, and on to Pell, and we can catch him there. He won't be expecting it."

"Out of the question."

"Hell with you!"

"Marie, let's talk sanity. He may not be going on to Pell. You may not know his schedule as well as you think you do. We're not going off in the dark with that ship. We're not equipped for that. No way in hell, Marie. No way in hell!"

She looked at the clock, jaw clenched, arms folded, as the minutes kept going. Let Mischa think he'd won. Let Mischa think he'd made his point.

"I can make the credit at Pell, Mischa. You load us for Pell and I can turn a profit." She lifted her hand. "Swear to God."

"Out of the bloody question."

"No, it isn't."

"For God's sake, that's across the Line, they'd charge us through the nose for a berth, we've no account there, and if you're right about Bowe, the kid will never see Pell…"

"The kid, the kid, the boy's got a name."

"Thomas Bowe-Hawkins."

Tried to make her blow her composure. But she knew what she was going to do, now. She knew. And when she knew, she smiled at him, cold and immovable as a law of physics.

"Pell," she said, "and we make a profit on the run. Or get yourself a new cargo chief."

"It's no bet."

"I'm not betting. I'm telling you. If it's not Pell—get yourself another cargo chief. I quit. I'll find a way to Pell."

"You're out of your mind, Marie."

"So you've said. To everyone in the Family. But you know how this ship was doing before, and how it's doing now. Cold, hard numbers, captain, sir. Iknow what I'm worth. I've got the numbers for Pell. No question I can make our dock charges andcome up in the black. Swear to God I can. Or I kiss you all good-bye, right here."

"Marie, this isn't even worth talking about. Go cool down."

"Cold as deep space, darling brother, and dead serious."

"That ship could be meeting some Mazianni carrier right out there at Tripoint in two weeks. We could run right into it."

"For what? Bowe told them he'd have a kid to trade them? They do those deals in the deep dark. Mazian's ships don't come in this far."

"We have rendezvous with our regulars, we have people's lives you're proposing to disrupt, appointments—"

"We'll get back on schedule. We'll all survive a little sexual deprivation."

"Try a sex life! It'll improve your mental health!"

"Mon-ey, Mischa. Mon-ey. Or poverty. Skimping to make ends meet, the way we did when dear Robert was running the cargo section. Because he willbe, again. Make your choice."

"You don't sit on this ship and not work."

"You weren't listening, Mischa, dear, I said I was leaving the ship. I'll find a way. I'm damned good. And goodships anywhere it wants to."

"As hired crew. You thinkyou'd like your shipmates on a hired-crew ship. Earn your way in bed, why don't you?"

"Because I don't have to. I can have passage on a Pell-bound ship in four hours, captain Hawkins, you watch me, because the numbers are in my head, and I'll use 'em, you'd better bet I will. I'm crazy Marie, aren't I?"

"You're talking like it."

"Fine! I'll put it to a vote in the Family, captain, sir, which of us this ship wants to have making the decisions. I'll tell you even Robert A. will vote to keep me, because hedoesn't want the job back, he doesn't want to lose his creature comforts. Neither do any of the seniors, and the juniors can't touch me! Let all the Hawkinses decide. I'll challenge you for the captaincy if I have to. And I have the right to call a vote."

"And make a fool of yourself! Everybody knows—"

"I'm sure you've told them often enough. Poor Marie. Poor crazy Marie. Poor crazy Marie who's the reason this ship runs in the black—"

"Poor crazy Marie who's the reason we lost Mariner for fifteen years! Poor crazy Marie who lost her nerve the only time she ever snagged a man, and started a riot that damn near ruined us! Anything you make for us is payback, sister, for what you cost us in the first place."

"Any trouble you had is because you sat on your ass for forty-eight hours. If you'd had the balls to do something before they got stupid drunk, I could have gotten out of there. But physicality just isn't your job, is it?"

"Maybe if you'd had a sex drive you could have handled what you asked for, damn you—duck out on us, ignore every piece of advice, no, you had to have your own pick, didn't you, and now he's got your kid? It's not my problem."

"Ask a vote, Mischa. Or I will."

Mischa didn't want it. That was clear. He stood there. And finally walked off across the bridge and stood staring at nothing in particular.

There were advantages to owning nothing, having nothing, wanting nothing in your life, except one man's hide.

And he couldn't have her kid.

Couldn't dispose of her kid. Or keep him.

That added something to the equation. She wasn't sure what, hadn't expected that reaction in herself, was still trying to understand why she gave a damn.

Because, she decided, if she'd had to hand one individual aboard Spriteover to Bowe for a hostage, it wouldn't be poor, people-stupid Tom, who was the first Hawkins to try to take her side in twenty some years.

Even if he had screwed it beyond all imagination.

Damn him.

—iv—

DREAM OF THE DARK AND NOWHERE, a lonely and terrifying no-thing, abhorring the fabric of the ship, and the ship almost… almost violating the interface.

The ship lived a day or so while the universe ran on for weeks, while the ship's phase envelope was the only barrier between you and that different space. You rode it tranked down, ever so vaguely aware of your own essence. When you were a kid the grownups admitted that the monsters you dreamed in transit were real, but (they said) the captain could scare the monsters off, because a kid believed in his imaginings, and a kid believed in adults just as devoutly.

But kid or adult, the mind painted its own images on the chaos—

Marie had told him pointedly there wasn't anything to meet out there but a body's own guilty conscience: if he minded what he was told he'd be fine and if he didn't he'd go crazy and be all alone with his misdeeds forever. He'd told that to the other kids and scared them. Aunt Lydia had said he was too smart for his own good. Aunt Lydia had said captain Mischa should have a talk with him, but Mischa had just said don't carry tales and don't talk about the dreams and don't make trouble, boy.

He dreamed about Marie sometimes. He'd dreamed about Mariner and the bar and the drunken men before he was twelve, then—it was between Fargone and Paradise, and he'd felt different things about Marie, sometimes scary, sometimes erotic, weaving back and forth in unpredictable ways, about all the things he'd heard happened, and about the things he'd read in tapes he wasn't supposed to have.

But he stole them, all the kids did, and they'd all tangled up…

That was only normal, aunt Lydia had said, when she'd found out. It was the first time she'd ever used that word about anything he'd done, and in spite of that, he didn't feelnormal. You didn't have dreams like that about your mother and feel normal.

But Marie had said, with rare (for Marie) calm, that he was growing up and he was confusing things, which was, for once, a better explanation than aunt Lydia gave. Marie gave him tapes, too, deep-tape, the same quality you used for school.

Only the tape gave him dreams and for a long time he dreamed about a robot, a wire-diagram woman who wasn't anybody in particular. She had a metal face, and he used to want her to sit on the end of his bunk and talk to him, not about sex, finally, just about stuff and about things he liked to do and where they traveled. She was a friendly sort of craziness, that lived in Marie's apartment and in his own quarters. Sometimes she had sex with him. And sometimes she just talked, sleeping by him, about ports they might go to someday.

But the metal-faced dream had died when he'd slept with his Pollycrewwoman. Or she'd gotten Sheila's face and become Sheila Barr, because the metal girl didn't ever come back again. He could just see her sort of standing forlornly behind Sheila's shoulder, looking a little curious and a little like the expression he saw in mirrors…

So maybe his wire-woman had become him, in some strange way.

But he'd damned sure never told Sheila who he dreamed she was, and never admitted it to aunt Lydia, who was so firmly, devoutly, desperately attached to other people's sanity.

Marie might have said, on the other hand, Hell, at least she won't get pregnant, and probably wished his wire-woman good morning at the breakfast table and asked did she want tea.

That was the way Marie had dealt with his childish fancies, made fun of them and sometimes fallen in with them. She said they were all right, she'd introduce them to hers sometime, and that had scared him, because he didn't think he wanted to meet Marie's dreams, in this space or any other.