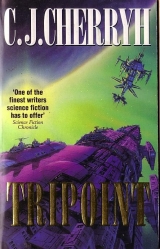

Текст книги "Tripoint "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Doors big as some ships. Stations didn't dothat. Not since the War.

"—We had two ships calling crew from all around the docks," Mischa said. "Station central was refusing to relay calls, threatening to arrest Corinthianand Spritecrew on sight, Madrigaland Pearlcrews were hiding some of our guys from the cops. I was in blue section, with about fifty of us. Corinthian, unfortunately, was docked right adjacent to blue. There were at least fifty of them holed up in the bar, about fifty more on deck, in blue, about that number of station cops and security, several hundred of our crew and theirs andcops stuck in sections they couldn't get out of. Forty-eight hours later, station agreed to total amnesty, we got Marie out, Corinthiangot Bowe and the rest of their crew out, and the bar owner's insurance company and the station admin split the tab. We agreed to different routes that wouldn't put us in the same dock again, which is how, by a set of circumstances, we ended up Unionside. And your mother turned up pregnant. That's the sum of it."

Mischa left a silence. Waiting for him to say something. He wanted to, finally ventured the question he wouldn't ask Marie.

"Was Austin Bowe the only one?"

"As Marie tells it, yes."

"As she tells it?"

"The captain's son, and in a hell of a bind? He knew she was his best bargaining chip. Only thing that mightget Corinthianout scot free was Marie, in one piece. She walked out of there.

Cut lip, bruises. Refused medical treatment, station's and ours. She was holding together pretty well for about the next twelve hours. She'd take the ordinary trank…"

The picture snapped into god-awful focus. "You took her into jump?"

"By the terms, we agreed to leave port."

"Marie wasn't the criminal!"

"Station had a riot on its hands. Station wanted us on our way. Mariewanted out of that port. Medical thought she was doing all right."

"My God."

"In those days, the guns were live, all the time. Hestonwanted out of there as soon as Corinthianjumped out. We weren't sure they weren't spotters, we didn't want them sending any message to any spotter that might be lying in wait out there in the dark—they did that, in those days, just lurk out on the edges, take your heading, meet you out at your jump-point—spotters didn't carry any mass to speak of. They'd beat you there. They'd be waiting. You'd be dead. We skimmed that jump-point as fast as we dared and we got the hell on to Fargone. It wasn't an easy run. We pushed it. You did things you had to do in those days, you took chances, the choices weren't that damn good, Thomas, it wasn't like today. No safety. When you were out there in the dark, you were out there with no law, no protection. We just hadno choice."

"It's a wonder she isn't crazier than—" He cut that off, before it got out, but Mischa said,

"—crazier than she is. I know. You thinkI don't know. I knew her before."

"Why didn't somebody orderan abortion? I mean, doesn't Medical just dothat, in a case like that?"

"The captains don't orderany such thing on this ship. Your mother said if she was pregnant, that was fine, she wanted…"

"Wanted what?"

Mischa had cut an answer short, having said too much about something Mischa knew, about him. But if he chased that topic, Mischa might stop talking.

"She said it was her choice," Mischa said, "and nobody else was getting their hands on her. I'll tell you something, Tom. There's not been another sleepover. No men. She won't get help. Your aunt Lydia studied formal psych—specifically with Marie in mind. Never did a damned bit of good. Marie copes just real well, does exactly what she wants, she's damned good at what she does. I'll tell you something. She wouldn't have any prenatal tests, wouldn't take advice, damn near delivered you in her quarters, except your grandmother found out she was in labor. Marie was dead set you were a daughter, and when she gave birth and found out you weren't, she wouldn't look at you, wouldn't take you, wouldn't hold you, until three days after. Then she suddenly changed her mind. All of a sudden, it's—Where's my son? And your aunt Lydia tells me some crap about postpartum depression and how it was a traumatic birth, and a load of psychological nonsense, but I know my sister, I knowthe look she's got; and I'm notdamn blind, Tom, I hoped to hell she'd turn you over to the nursery, which she did when she found out she really hated diapers, and being waked up at odd hours. I wasn't for it when she wanted you to come back and live with her. I really wasn't for it, but your grandmother always hoped Marie would straighten out, sort of reconcile things… small chance. I watched you and her, damned carefully. Mama did. I don't know if you were aware of that."

Blow across the face. Didn't know why. He didn't know why mama ever did things, one minute hit him, another held him, Marie had never made sense about what made her mad. Call her Marie, not mama, that was the first lesson he learned. Marie was hismother, and finally, finally she took him home to her quarters like the other kids' mothers—but if he made her mad or called her mama she'd take him back and the other kids would know…

Which she did. More than once.

"Were you?" Mischa asked, and he didn't know what Mischa had just said.

"I'm sorry, I lost it."

Long silence, long, long silence in the captain's office, himself sitting in front of the desk, like a kid called in for running, or unauthorized access. Damn Mischa, he'd thought he understood, he'd thought Marie was right. Now he didn't know who'd lied or what was real or how big a son of a bitch Mischa was, after all.

"I can't control Marie," Mischa said. "Your grandmother might've, but she's gone. I've talked to her. Ma'am's talked to her. Your aunt Lydia's talked to her. Said—You're hurting that boy, Marie, he's too young to understand, he doesn't know why you're mad at him, and for God's sake let it be, Marie. Which did damned little good. Marie's not—not the kid that went into that sleepover. She'd hold a grudge, yes. But nothing like—"

Another trail-off, into silence. Maybe he was supposed to fill it. He didn't know. But he still had his question.

"Why didn't she abort? What was it you almost said she wanted?"

Mischa didn't want that question. Clearly.

"Tom, has she talked to you about killing Austin Bowe?"

"She's mentioned it. Not recently. Not since I moved out on my own."

"She ever—this is difficult—do or suggest anything improper?"

"With me?" He was appalled. But he saw the reason of Mischa's asking. "No, sir. Absolutely not."

"The answer to your question: she said… she wantedAustin Bowe's baby. And she wouldn't abort."

It rocked him back. He sat there in the chair not knowing what to say, or think.

Marie'd said, just an hour ago, she'd kept him because shechose what happened to her. Obstinacy. Pure, undiluted Marie, to the bone. He could believe that.

But he could… hearing the whole context of it… almost believe the other reason, too. If he could believe Mischa. And he did, while he was listening to him, and before Marie would turn around and tell him something that made thorough sense in the opposite direction.

"Wanted his baby," he said. "Do you know why, sir?"

"I don't. I've no window into Marie's head. She said it. It scared hell out of me. She only said it once, before we jumped out of Mariner. Frankly—I didn't tell your grandmother, it would have upset her, I didn't tell Lydia, I didn't want that spread all over the ship, and Lydia's not—totally discreet. I didn't even know it was valid in the way I took it. She'd been through hell, she never repeated it in any form—it's the sort of thing somebody might say that they wouldn't mean later."

"Have you asked her about it?"

Mischa shook his head, for an answer.

"Shit."

"Thomas. Don't youask her. She and I—have our problems. Let's just get your mother through the next week sane, that's all I'm asking."

"You throw a thing like that at me, and say… don't ask?"

" Youasked."

He felt… he wasn't sure. He didn't know who was lying, or if Marie was lying to herself, or if Mischa was deliberately boxing him in so he couldn't go to Marie, couldn'task her her side.

"What do you want me to do?"

"Has she talked—down below—about killing anyone?"

"She said—she said she wants to get at him through the market. Legally."

"You think that's true?"

"I think she's good at the market. I think—there's some reason to worry."

"That she might pull something illegal? Damaging to us?"

If Mischa's version of Marie was the truth—yes, he could see a danger. He didn't know about the other kind of danger—couldn't swear to what Marie had said, that she wouldn't take to anybody with a cargo hook, that it wasn't her style. Cargo hook was Marie's imagery. He hadn't thought of it.

"What are you going to do?" he asked Mischa.

"Put Jim Two on it—have him watch her market dealings every second. Have yougo with her any time she goes onto the docks. And you remember what she pulled on me and Saja. You don't take your eyes off her."

"You're going to let her go out there."

"It's a risk. It's her risk. It's forty years ago station-time, like I said, probably Viking has no idea it's got a problem—but ships pass that kind of thing around. Somebody out there knows. Damned sure Corinthianhasn't forgotten it, and I'm hoping Bowe isn't as crazy as Marie is. He's got no good reputation, Corinthian's still running the dark edges of the universe—damned right I've kept track of him over the years—and I don't think he wants any light shining into his business anywhere. If he's smart, and I've never heard he was a fool, he'll find reason to finish business early and get out of here. I'll tell you I'm nervous about leaving port out of here with him on the loose—war nerves, all over again. But there's nothing else I can do. We've got a cargo we've got to unload, we've got servicing to do, we just can't turn around faster than he can and get out of here."

"You really think in this day and age, he'd fire on us?"

"He didn't acquire more scruples in the War. Damned right he would, if it served his purpose. And if he hasn't tagged Marie as a dangerous enemy, he hasn't gotten her messages over the years."

"She's communicated with him?"

"Early on, she sent him messages she was looking for him. That she'd kill him. She's dropped word on crew that use his ports. Left mail for him in station data. Just casually."

"God."

"Dangerous game. Damned dangerous. I called her on it. Told her she was risking the ship and I told Heston. But stopping Marie from anything is difficult. I don't thinkshe kept at it."

"And you're asking me to keep tabs on her?"

"You better than anyone. Take her side. There's nobody else she'd possibly confide in."

"Why, for God's sake? Why should she tell me anything?"

"Because you're Austin Bowe's son. And I think you figure somewhere in her plans right now."

"My God, what do you think she's going to do, walk onto his ship and shoot him?"

"If she's got a gun it's in spite of my best efforts. They're not that easy to get nowadays. And Marie may not have ever expected to have her bluff called. I haven't gotten information on Bowe's whereabouts all that frequently—frankly, not but twice in the last six years, and that had him way out on the fringes. I didn'texpect to run into him here. No way in hell. But he is here. And even if she was bluffing—she's here, and it's public. This isn't going to be easy, Thomas. I may be a total fool, but I think she'll go right over the edge if she can't resolve it now, once for all. She's my sister. She's your mother. She has to go to the Trade Bureau like she always does, she has to do her job, she has to walk back again like a sane woman, and get on with her life. If Corinthianleaves early, that's a victory. Maybe enough she can live with it. But it's going to scare hell out of me."

"You think he will leave?"

" Ithink he will. I think he's on thin tolerance at certain ports. I think he's Mazianni, I've always thought so. His side lost. I don't think he'll want to do anything. Just her crossing that dock with you is a win, you understand me? Calling his bluff. Daring him to make a move."

"Does he know about me?"

"I think she's seen to it he knows."

That scared him. Anonymity evaporated, and anonymity was the thing he cultivated on dockside, for a few days of good times notto be Thomas Bowe, just Tom Hawkins, just a crewman out cruising the same as everybody else on the docks. He was famous enough on Sprite, with every damn cousin, and his uncles, his mother and an aunt hovering over him every breath, every crosswise glance, every move he made subject to critique, as if they expected he'd explode. And now captain Mischa was sending him out dockside with Marie?

Two walking bombs. Side by side. With signs on them, saying, Here they are, do something, Austin Bowe.

He sat there looking at Mischa, shaking his head.

"If she goes out there and she does something," Mischa said, "the law will deal with her. And do you want Marie to end up in the legal system, Tom, do you wantthem to take her into some psych facility and remove whatever hate she's got for him? Do you want that to happen to Marie?"

He couldn't imagine permanent station-side. Never moving. Dropping out of the universe. Foreign as an airless moon to him. And as scary. Mind-wipe was what they did to violent criminals. And they'd do that to Marie if she went for justice. "No, sir," he said. "But you're trusting me?"

Mischa said, "Who have I got? Who willshe deal with? There'll be somebody tagging you. You won't be alone. You just keep with her. If you can't do it any other way, knock her cold and bring her back on a Medical, I'm completely serious, Tom. Don't risk losing her."

Nobody trustedTom Bowe-Hawkins. Saja hadn't trustedhim when he'd passed his boards, as if he was going to blow up someday and do something illicit and destructive to the ship's computers.

"You know," Mischa said, "if youdid anything to Corinthiancrew, you'd fare no better in the legal system. Station law doesn't know you. Station doesn't give a damn for ship-law. It's not a system you'd ever want to be part of."

"Yes, sir," he said. Mischa'd had to say that last, just when he'd thought Mischa might have trusted him after all. "I hear you. Does this make me one of you?"

Silence after that impertinence. Long silence.

"Where does that come from?" Mischa asked.

Didn't the man know? Didn't the man hear? Was the man blind and deaf to what he was doing when he pulled his psych games?

When the kids in the loft painted Korinthianon his jacket?

When the com called him to the bridge an hour ago as Thomas Bowe—the way Marie had enrolled him on the ship's list, three days after he was born?

"You're not the most popular young man aboard," Mischa said slowly. "I think you know it. I know you've had special problems. I know they're not all your fault. But some things are. You've got try-me written all over you. You're far too ready with your fists, even in nursery you were like that."

"Other kids—"—went home with their mothers, he started to say, and cut that off. Mischa would only disparage that excuse.

"Other kids, what?"

"I fought too much. My father's temper. I've heard it all."

"You got a bad deal. I'm sorry, but, being a kid, you didn't make it better. Do you know that?"

"I gave back what I got. Sir."

"You listen to me. You made some mistakes. I'm saying if you get through this situation clean, it could help Marie. And it could change some minds, give you a position in this Family you can't buy at any other price. For God's sake, use your head with Marie. She's smart, she's manipulative as hell, she'll tell you things and sound like she means them. Above all else, get that temper of yours well in hand. I can't control what everybody on this ship is going to say or do in the next few days. That's not important. Getting this cargo offloaded and ourselves out of this port with all hands aboard—is. Don't embarrass Marie. Let's get her out of here with a little vindication, if we can do that, and hope to hell we don't cross Bowe's path for another twenty of our years."

Mischa Hawkins gave good advice when he gave it. Didn't domuch for him, the son of a bitch, but what did Mischa Hawkins actually owe him?

"I'll do my best," he said. "I'll do everything I humanly can."

Mischa stared at him a moment, estimating the quality of the promise, or him, maybe. Finally Mischa nodded.

"Good," Mischa said, pushed the desk button that opened the door, and let him out.

Do something to clean up hisreputation. What in hell had hedone?

God!

He didn't punch the wall. Didn't even punch the nearest cousin, who passed him in the corridor, with a cheery, "Well, what's the matter with you, Tommy-lad?"

He went downside to the deserted gym, dialed up the resistance on the lift machine, and worked at it until he was out of breath, out of brain, and draped completely limp onto the bar.

Things had been going all right until that blip showed up on the display.

Marie had been all right, he'd been all right, he'd gotten his certificate, grown up like the rest of Sprite'sbrat kids, passed the point of teenage brawls, gotten his life in order…

Go rescue Marie from blowing Austin Bowe's brains out? On some days he'd as soon wish her luck and hope they got each other. He didn't want to meet his biological father. There were days of his life he wanted nothing more than to space Marie.

There were whole hours of his life he knew he loved her, no matter what she did or how crazy she was, because Marie was, dammit, his mother—not much of one, but he was never going to get another one, and he always felt—he didn't know how—that somehow if he could grow smarter or act better, he could eventually fix what was wrong.

Take-hold rang. He went to the back wall of the gym and stood there while the passenger ring went inertial and the bulkhead slowly became the deck. They were headed in.

One could walk about the walls during gentle braking, if one had somewhere urgent to be and a good idea how long the burn was going to last. Easier just to shut the eyes and lie on the bulkhead and let the plus-g push straighten out a tired, temper-abused back.

Fool to go at the weights in a fit of temper. Only hurting yourself, aunt Lydia would say. He was. But that was, Marie's own claim, at least his choice, nobody else's.

—iii—

PROGRAM CAME UP, PROGRAM RAN, categorizing and digesting the informational wavefront from the station, and Marie made a steeple of her fingers, watching the initial output.

She regretted the dust-up on the bridge, but, damn it, Mischa had known he was pushing. Mischa deserved everything he got.

Crazy, Mischa called her, in private and behind her back.

And so, so considerate of Mischa to spare her feelings… in public, and all.

Viking was at mainday at the moment, halfway into it, the same as Sprite'sship-time. But Corinthianwas an alterday ship. Corinthianran on that shift. Her principal officers awake during that shift: that meant the juniors were on duty right now.

That suited her.

Rumor had always maintained that certain merchanters had close operational ties to Mazian's Fleet, back in the War. The Earth Company called them loyalists, Union called them renegades. Merchanters called them names of fewer letters. Most merchanters had taken no side during the early stages of the War—Earth Company, Union, it was all the same: whoever had cargo going, at first you hauled it—until the EC Fleet stopped ships, and appropriated cargoes as Military Supply and took young crew at gunpoint, as draftees. After that, most merchanters wouldn't come near the Fleet.

And when, at the end of the War, Mazian hadn't surrendered, but kept on raiding shipping to keep the Fleet alive, there were certain few ships who, rumor had it, still tipped him about cargoes and schedules—and picked off the leavings of the raids, pirates themselves, but a small, scavenging sort.

And, no less despicable, some ships still reputedly traded with the Mazianni… ships that disappeared off the trade routes and came back again loaded. The stations, blind to what happened outside the star-systems, were none the wiser, and with the Union and Alliance governments limited by the starstations' lack of interest in the problem.

But deep-spacers whispered together in the bars, careful who was listening. And sheregularly caught the rumors, and sifted them through a net of very certain dimensions—since stations claimed they didn't have the ability to check on every ship that came and went… since stations were mostly interested in black market smuggling of drugs and scarce metals and other such commodities as affected their customs revenues.

Very well. Viking didn't give a damn until the mess landed on its administrative desk. Viking certainly didn't remember what lay forty years in the past as Viking kept time. Viking wasn't going to call Corinthianand say there was a problem. Oh, no, Viking, like every other station, was busy looking for stray drugs or contraband biologicals.

And the fact that particular ship was on alterday schedule might give Spritethat much extra time to get into port before senior Corinthianstaff realized they had a problem: their arrival insystem had to come to Corinthianoff station feed, since a ship at dock relied on station for outside information—and how often did a ship sitting safe at dock check the traffic inbound?

Not bloody often. If ever. Though Corinthianmight. Bet there was more than one ship that had Corinthianon its shit-list.

She owned a gun—illegal to carry it, at Viking or in any port. She kept it in her quarters under her personal lock. She'd gotten it years ago, in a port where they didn't ask close questions. Paid cash, so the ship credit system never picked it up.

Mischa hadn't figured it. Or hadn't found where she kept it.

But it was more than Austin Bowe that she tracked, not just the whole of Corinthianthat had aided and abetted what Bowe had done, and there was no more or less of guilt. Nobody got away with humiliating Marie Kirgov Hawkins. Nobody constrained her. Nobody forced her. Nobody gave her blind orders. She worked for Spritebecause she was Hawkins, no other reason. Mischa was captain now, yes, because he'd trained for it, but primarily because the two seniors in the way had died—she was cargo chief not because she was senior, but because she was better at the job than Robert A. who'd been doing it, and better than four other uncles and aunts and cousins who'd moved out of the way when her decisions proved right and theirs proved expensively wrong. No face-saving, calling her assistant-anything: she was damnedgood, she didn't take interference, and the seniors just moved over, one willingly, four not. The deposed seniors had formed themselves an in-ship corporation and traded, not too unprofitably, on their ship-shares, lining their apartments with creature-comforts and buying more space from juniors who wanted the credits more than they minded double-decking in their personal two-meter wide privacy. So they were gainfully occupied, vindicated at least in their comforts.

She, on the other hand, didn't give a running damn for the luxuries she could have had. She'd had room enough in a senior officer's quarters the couple of times she'd brought Tommy in (about as long as she could stand the juvenile train of logic), so she'd never asked for more space or more perks, and whether or not Mischa knew who really called the tune when it came to trade and choices, Spritewent where Marie Hawkins decided it was wise to go, Spritetraded where and what Marie Kirgov Hawkins decided to trade, took the contracts she arranged.

Mischa wouldn't exactly see it that way, but then, Mischa hadn't an inkling for the ten years he'd been senior captain exactly which were his ideas and which were hers. As cargo chief she laid two sets of numbers on his desk, one looking good and one looking less good, and of course he made his own choice.

Now Mischa was going to explain about Marie's Problem to poor innocent Thomas, and enlist his help to keep Marie in line? Good luck. Poor Thomas might punch Mischa through the bulkhead if Mischa pushed him. Thomas had his genetic father's temper and Thomas wasn't subtle. Earnest. Incredibly earnest. And not a damn bad head on his shoulders, in the small interludes when testosterone wasn't in the ascendant.

Predict that Mischa would want to deal with Tom, now, man to man, oh, right, when Mischa had ignored Tom's existence when he was a kid, when Mischa had resisted tracking him into mainday crew until Saja pointed out they'd better put a kid with his talent and his brains under closer, expert supervision. Every time Mischa looked at Tom, Mischa saw Marie's Problem; Mischa had a guilty conscience about younger sister's Problem, and Mischa was patronizing as hell, Thomas hated being patronized, and Mischa hated sudden, violent reactions.

Gold-plated disaster.

Best legacy she'd given Bowe's kid—awareness when he was being put upon. That, and life itself. End of her debt of conscience, end of her personal responsibility and damned generous, at that. So Tom was getting to be a human being. End report. Tom was on his own. Twenty plus years of tracking Austin Bowe, and she was here, free, owing nobody but that ship—a little before she'd wanted to be, but one couldn't plan everything in life.

It didn't particularly need to involve Tom. She'd acquired that small scruple. Leave Tom to annoy his uncle Mischa, if for some reason she wasn't around to do the job.

Nice to have a clear sense about what one wanted in life. Nice to have an absolute and attainable goal.

Mischa could never claim as much. But, then, Mischa forgave and forgot. Rapidly. Conveniently—if Mischa got what he wanted, and you could spell that out in money and comfort and an easy course, in about that order.

Not her style. Thank you, brother. Thank you, Hawkinses, every one.

Spritemight have come and gone peaceably at Viking for three, maybe four long rounds of its ports, exchanging loops with Bolivar, without chancing into Corinthian'spath. That wouldn't have kept the data out of her hands—recent data, of Corinthian'scurrent activities. Spriteand Corinthiannever even needed to have met face to face in order for her to have what she wanted.

Watching Austin Bowe sweat? That was a bonus.

Her chief anxiety now was the surprise of the encounter—before she had enough of that most current data. The last thing she wanted was for that ship to spook out suddenly and change patterns on her. She wanted to be a far greater problem to Corinthianthan that.

Still, she improvised very well.

Loosen up, Austin Bowe had told her, on a certain sleepover night. Adapt. Go with what happens. You're too tense.

Best advice anybody had ever given her, she thought. He'd meant sex, of course. But he'd meant power, too, which—she'd known it that night—was what that encounter had been all about, a teen-aged kid's conviction that she ran her own life, up against a thorough-going son of a bitch, not much older, used to his own satisfaction. Thatwas the mistake in scale Austin Bowe had made. Her motives and ambitions hadn't been that important to him… then. She'd played and replayed that forty-eight hours in her head, and after the first few weeks, the rape itself wasn't as bad as having had to walk out that door, the physical act hadn't been as ultimately humiliating as herdamned relatives, dripping pity and so, so embarrassed she'd been a fool going off by herself, relatives so upset—it was clearer and clearer to her—that she'd damaged the reputation of the ship, humiliated her relatives, gotten them all ordered out of port—and they were all so, so disappointed when she didn't shatter and come crawling to their damned condescending concern.

Hell, she got along fineafter that, except their hovering over her and waiting for Marie to blow up. After mama died, Mischa took over the hovering, and Mischa had said to her and everybody who was interested that she'd be just fine if she ever found herself the right man.

That was funny. That was downright pathetically funny. Mischa thought if she just once got good sex she wouldn't want to kill Austin Bowe.

Or Mischa Hawkins.

Sex good or bad hadn't put Austin Bowe in charge of Corinthian. It might be gender, genes, family seniority, even, God help them, talent; but it sure as hell couldn't be his performance in bed, and damned if hers that night had measured Marie Hawkins' capacities, any more than Mischa's self-reported staying power in a sleepover meant he was fit to captain Sprite.

—iv—

DAMN COM BEEPED. INSISTENTLY. If it wasn't a screaming emergency, the perpetrator was dead.

Austin Bowe reached out an arm from under the covers, in a highly expensive station-side room, seeking toward the red light in the dark.

Which disturbed… whatever her name was. Who moaned and shifted and jabbed an elbow into his ribs as he punched the button.

"Austin.—What in helldo you want?"

" Sprite'sinbound."

He blinked into the dark. Thoughts weren't doing too well. Too much vodka. The fool woman sat up and started nuzzling his neck. He shoved her off. Hard.

"Captain?"

"Yeah, yeah, I copy." The brain wouldn't work. The body felt like hell. "Have we had any word from them?"

"No. They're in approach."

"What the hell are you doing on watch? Is this Bianco?"

"Yes, sir."

"They're in approach."

"I'm sorry, sir. No excuse. About two hours from mate-up."

"That's just fucking wonderful. Can we not discuss it here, possibly? Where's Christian?"

"I—hate to tell you this, captain."

"All right, all right, findhim. Dammit!"

"What are we to—?"

"Make it up, Bianco, damn your lazy hide, we've got a problem. Use your ingenuity!"

What's-her-name put an arm around his neck. Said something he wasn't listening to. Beatrice was on the dock somewhere. Their son was likewise somewhere on the docks, supposedly seeing cargo moved, but Corinthiandidn't know where Christian was at the moment?

"Aus-tin," the woman said. "Is something wrong?"