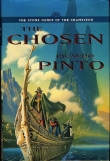

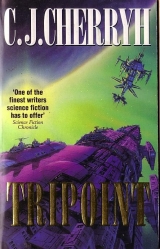

Текст книги "Tripoint "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

"Pell's where we're going?"

"Yeah. If you get dock time, if you want to go, you can come with me. It's an hour tour."

"I don't think they're going to let me."

"More'n you just backtalked the captain, isn't it?"

Tink wasn't so slow. "Yeah," he said. "Don't think he's ever wanted me alive, let alone on his ship."

"Huh," Tink said. That was all. And his estimate of Tink's common sense went way up.

—iv—

THE LIGHTS DID THAT BRIEF DIMMING and rebrightening that was maindawn and alterdark, that ancient re-set of biological clocks for the two main shifts together, that odd time that two entire crews who shared the same ship should meet and cross and exchange duties. One shift's first team was eating breakfast, one shift's first team was eating supper, while the seconds of one shift were making ready for switchover and the seconds of the other were at supper if they liked, or rec, or sims or whatever… it was a great deal the same as on Sprite, a great deal, Tom supposed, the same on every ship in space, a lot the same on stations, so it must say something about what Earth did or had done… he'd never figured, but he supposed so.

Officers' mess was elsewhere… Tink put pans on a cart, no different at all went into it than the general crew got, by his observation. One pastry went to the officers, one to the crew, set out on the sideboard, on display, and on the breakfast-dinner line you could have whatever appealed to you, Cook said, just dish up what they wanted, no quotas, no fuss. Meanwhile they had their own meal, himself and cook, whose proper name was Jamal. Cook was all right, seemed to like him. Jamal had what looked like knife scars on his arms and down the right side of his face, and he'd never seen anybody carry scars like that. But he guessed Jamal hadn't been where he could get to meds, or didn't want to, or some reason he'd never met in his life.

Jamal wasn't the only one. The crew that drifted in… just wasn't likethe people he associated with, which meant like Hawkinses, and the safe bars and the high-class sleepovers of Fargone and places Sprite went. Men and women had missing fingers, marks of burns here and there, what he took for old cuts, stuff, God, a surgeon could still fix, along with guys clearly over-mass, and one woman blind in one eye. He saw tattoos, and shaved heads or long hair—he looked at the first arrivals with the panic feeling he'd walked into the wrong bar. But he stood his ground, behind the fortification of the hot line.

"Well, well, well," the comments ran, from female andmale, "look at you, pretty."

Or: "Reluctant sign-up, looks like."

Or: "Hey, cook, something newon the menu?"

"Name's Tom Bowe-Hawkins," Jamal said.

"Bowe," the murmur went around.

He just dished up the meatloaf and gave a tight-lipped smile at the offender.

After that it was quieter, with him dishing out main items while cook handled the pastry-cutting—Tink was right, the boundaries among the flowers and vines were as disputatious as trade negotiations.

He could relax after that. The crew looked like dockside hustlers, but the humor wasn't anywhere totally out of line. He snatched a bite himself, the meatloaf, having counted what drew the most second helpings. It was good. He managed to have a mostly uninterrupted supper, give or take the late arrivals who came trailing in. Pastry was as good as it looked, real cake, which meant flour, which wasn't easy come by or cheap—you usually got it on special occasions or in stations' fancier restaurants, at ferocious prices.

Lot of money. Or—he revised the thought—just nearness to the source—and Pell, where they were bound, was a source. You couldn't prove anything against Corinthianby the sweets and the cake. He didn't have to think it was stolen.

It wasn't, overall, too damn bad a situation. The crew ragged him, but he'd had that everywhere. He just kept his head down, kept his panic reaction in check, and did his work and didn't bother anybody… didn't look for another run-in with Austin Bowe down here in crew territory, and that made him easier with the company he did have.

He finished the cleanup and helped set up mid-shift snacks, the sort that got delivered out. And it was scrub down the galley and the filters again… not a big job, because Jamal wanted it done every meal, and a rinse with detergent would do it.

The galley's standards didn't speak of a sloppy ship, at all.

"Guys don't look real regulation," he remarked to Tink, when he and Tink were working side by side; and he'd gotten so used to Tink's appearance he forgot he was saying that to a guy whose arms were solid tattoos of snakes and dragons.

"Hey. You stick with me, I know a good artist on Pell. Glow in the dark."

He couldn't imagine. Couldn't imagine going back to Spritewith a tattoo.

And then he recalled where they were, traversing the dark of Tripoint, on their way to places Spritewouldn't find them, didn't care to find them, and he got a lump in his throat and asked himself what he was going to do—except Tink had had things a hell of a lot worse, and he told himself somehow he couldsurvive, and there wasa future.

"You worried about the crew?" Tink asked him.

"No," he said. "Not really."

"A lot of these guys, like me," Tink said, and shoved a filter into its slot, "you knock around a lot, you know. Play hob getting work. You get a real solid berth, you damn sure appreciate it. Some's dockers, however. You may have detected."

"Its own dockers, this ship?" That wasn't usual. You hiredyour off-ship workers. You had to, far as he'd ever heard Marie deal with cargo. But maybe if a ship really didn't want outsiders handling its cargo…

Tink didn't answer right off. Maybe it was something Tink wasn't supposed to say. Maybe it was a question he wasn't supposed to ask. "Hey, the unions want to insist, all right, our guys handle it to the gateway, they take it after. And most of these guys are all right. Just ever' now and again you figure they got a little stash they're hitting… the long, deep dark's the place they get spooky. They don't got enough to do. They start hitting the stash, you know, four, five days… that don't improve their personality a bit."

"I wouldn't think. " Maybe he really shouldn't have asked. It dawned on him—if there were trades in the deep, and that was Corinthian'sbusiness—even there, somebody had to handle cargo, and umbilicals, and all the mate-ups, in an exchange of cargo, or whatever. Dockers… were what you needed in that operation, dockers and cargo monkeys, not your tech crew.

Tink got up and dusted his hands. "I got to get a new overhead filter. This indicator's turned."

Definitely shouldn't have asked, he thought to himself. "Yeah," he said, "all right. " As if his approval meant anything. Tink terminated the conversation, went off to storage to look for the right filter—Tink wasn't lying about that, he was sure.

Tink stayed gone a bit. Possibly, he thought, there wasn't a filter in stock where it ought to be… if that happened, you had to check other lists, because usually you could sub something, but you also chewed out Supply, and asked why the computer hadn't reported it.

If it hadn't, hecould fix it, instead of scrubbing tables—if he wanted to admit he knew enough to be a danger to the ship. Which he didn't intend to do, not without knowing more than he did, not without some sort of peace between him and Corinthian, that maybe seemed a little nearer since he'd dealt with Tink, but far from certain, since there were clearly right questions and wrong questions and things Tink didn't want to discuss on his own.

A good thing, was it, for hired crew? Maybe the best berth any of them could ever hope for? The ship paid… damned well, evidently. Evidently the ship could afford it without a blink. In either case one had to ask—

Latecomers arrived, a noisy six, seven crewmen who'd missed the serving hour, who saw the food line taken down and weren't happy. "Jamal?" one called out, and got no answer.

Guys who thought they might not get supper weren't a happy lot, and he was uneasy being out front instead of behind the counter, in the galley-proper, where only galley personnel belonged, according to the sign. He went over to the gap in the counter, eased past a guy standing in his way.

"Tink's here," he said, "he just stepped out. He'll be back—"

The man behind him stepped on the cable, jerked his arm.

"Who are you?"

"Tom Hawkins. Tom Bowe-Hawkins. " That name had never been an asset in his life, but it seemed that way now. "Excuse me. " He closed his hand on the cable to pull it free, looking at the man dead on. The trouble warning was flashing through his nervous system. It doubled when the guy didn't move his foot. "I pay favors," he said.

"Well, what aboutsome favors?" the clown said. "You handing it out, boy?"

"You want meals off-schedule, you ask and say please, or you talk to Cook about—"

The guy jerked the cable. He was ready for it, but the guy outweighed him. He had the counter corner between them. He used that for a brake, but the pull put his arm in hostile territory and hurt a wrist getting sorer by every pull on it—hurt it considerably, and the guy grabbed his arm to jerk him around the counter and into the galley.

Another jerked on him and he got him—threw all the weight he owned at the target he found clear—the guy's throat, that being what he exposed, and grabbed the guy's sleeve as he slid across the counter and the others closed in. He had one hand free, the other was tangled with the cable, and he couldn't swing, but he tried to grab the cable and get it around a neck, any neck, he wasn't particular. He got part-way up when he landed, got hits in anywhere he saw open, between efforts to keep them from doing a complete take-down, the way they were trying, not just the one, all of them. "Get him, get him, get him," someone yelled, and as the sheer weight shoved him down, his head hit the cabinet handle, boomed off the doors, his shoulders hit the floor and five or six guys were piling on him, weighing his legs down, hanging onto his arms. A blow caught his temple and knocked him blind, a knee landed in his gut, and he kept trying to swing, but he couldn't get the one hand clear, couldn't get out of the vee they'd jammed him into, and couldn't fend the next blow or the next or the next…

"What in hell are you doing?" somebody yelled, and he kept trying to swing—caught one with his elbow. "Break it up. Now, damn it! Break it up!"

Somebody waded in and pulled the guys off him, told them to get the hell out—didn't sound like Jamal, didn't sound like Tink… he still hadn't gotten his sight back, but whoever had gotten them off ordered them out, said he wouldn't put them on report, just get the hell out. "This is my brother," somebody yelled next his ear, the same somebody holding him on his feet. "You lay a hand on him again and I'll kill you."

Christian? He didn't believe it—but somebody who called him brother was holding him up, arm around his bruised ribs. His knees weren't working at all well, he couldn't get his breath. One of them had hit him in the gut, and he couldn't keep his feet when his rescuer let him down to the deck against the cabinet and lifted his eyelids one after another.

"'m all right," he said, trying to get his wind back. "Can't see—they caught me one in the head."

"Goes away," Christian said, and it was, to the extent he could make out lights and darks, the white of the floor, the dark of Christian's knee. He was preoccupied getting his breath and still didn't comprehend why Christian who'd given him, hell till now was holding him from falling on his face—his Pollygirl'd hold him like that, defend him like that, but, different, he thought dimly, different, never had anybody pull him out of a fight who hadn't likewise lit into him, and him being close to falling on his face, and the rescue being somebody he didn't otherwise trust… he didn't know what he thought or felt… whether he resented it or didn't when Christian shouldered his weight, ran a hand through his hair and called him a damned ass in a tone gentler than Marie ever used with the same endearment.

Stupid to trust the guy who'd jerked him up a wall on a cable.

But Christian dug a key-card out of his pocket, and used it on the cable lock, just took it off, and rubbed his wrist and pulled at him. "I'll give your regrets to Cook. Come on. Up. Up."

He didn't know what he thought. Didn't understand the game, but he hurt, he couldn't see, and up on his feet was where he wanted to be, except the whole room was tilted. Christian kept him upright—kept him from falling on his face—he was seeing blurry tables in a vacant galley, now.

And Tink came back.

"What's going on?" Tink asked. "I just stepped out to storage, sir, I was with him all the time—"

"Six, seven fools," Christian said. "I got him, Tink. He's all right. I'll fix him up."

He wasn't sure about that proposal. He wasn't sure he wanted Christian taking him anywhere, and he wanted Tink to stick with him, but Tink didn't raise any objection as Christian steered him past the tables and out the door—what could Tink do anyway? Christian was an officer on this ship.

It was up to him, then. He made a try at walking on his own, but he still couldn't see anything but shapes, and he wasn't, it turned out, walking straight. Christian threw an arm around him, hauled him away from impact with the wall.

"Don't be an ass," Christian said, "difficult as that may be for you."

"Go to hell."

Christian jerked him hard enough his head snapped. "I can beat up on you. They can't. That's the rules."

Seemed perfectly clear. He got a breath as they walked. "Where're we going?"

"My cabin."

He planted his feet. Tried to. He wasn't at all stable, even standing, and Christian dragged him along anyway. By now his vision was clearing, but a headache arrived with it, and he thought a bone in his forearm might be cracked, where Christian was pulling on it.

Another jerk. "Don't give me trouble."

Hurt, being hauled on like that. Didn't have the brain operative enough to argue otherwise, and he thought for a moment he was going to throw up, right there in the corridor. He didn't want to do that. Wanted a bathroom, wanted to sit down, and if Christian had a place closer than he could otherwise get to, fighting wasn't worth it yet, wait-see… hope the rescue was a rescue and not an ambush in itself.

Christian steered him for a blurry door, opened it, on a wide cabin with real carpet. Chairs. Bunk. Lot of pillows.

"Don't bleed on the bed. " Christian dropped him onto it. "You hear me?"

He wasn't trying to. He was looking for somewhere to lean his hand, but it was bleeding or bloody, his nose was bubbling, and Christian went back to the bath and ran water while he considered whether he was or wasn't going to heave his gut up.

Not, he decided after several breaths and a wait-see. He propped himself with his hand on his knee, mildly tilted, on the edge of the bed, while Christian brought him a wet towel and insisted on going at his face with it, mopping his nose and his mouth, his eye. He was shaky. The cold towel obscured his vision and he wasn't sure where up was. The tilt warned him.

Christian shoved him backward, flat, and said catch his breath.

Good idea, he thought. But it rode his thoughts consistently that Christian wasn't his friend, the captain of the ship had ordered him to be in the galley, and if there was a set-up for blame possible, Christian wasn't necessarily the one going to catch hell—he just couldn't think through the haze and the headache to figure out what the game was.

"Listen," Christian said, settling, a weight on the mattress edge beside him. "The guys made a mistake. I don't want it blown up into an incident that can sour this trip, you read me clear? Mad crew can make a lot of trouble."

It sounded like an actual honest reason. A serious reason. He wasn't brought up a total fool—a ship in space was wholly vulnerable. This ship in particular was vulnerable to its hire-ons or any total crazy they happened to get aboard. Was Christian saying they were already running scared of the crew, or what, for God's sake? And was Christian in some kind of personal bind about what had happened?

His head hurt too much to figure it out. Christian meanwhile got up and rummaged through his clothes locker, after something, he didn't figure what, or want to know. He just wanted back in the galley or back in the brig without being used or manipulated into something that could bring their mutual father to bounce his already aching body off the bulkhead again, that was his chief concern. He'd just had it fairly good where he was, today, and he didn'twant a set-to with anybody right now.

Except—

Christian came back, threw some clothes onto the end of the bed. "You concussed? Anything broken?"

He ran his tongue around his mouth as he lay there. Stared at Christian down his nose. There were cuts. Teeth ached. Everything ached. "Ribs, arm, maybe cracked. I don't know. " He couldn't help it, couldn'tkeep his mouth shut and give up a fight with a guy who had one due. "What's it to you?"

"All right, all right. " Christian waved his arms. "Cancel, stop, go back. Bad start, all right? Bad start. My damn temper.—But I caught hell for bringing you aboard. Austin calls me a fool. Everybody calls me a fool. But it was a judgment call. Don't ask me what I was supposed to do! You're the one went poking into what didn't involve you, and now everything's my fault. When I'm wrong I catch hell for it. When I'm right I catch hell. When I'm right and they're wrong I catch double hell, but I didn't plan this, I did the best I could, all right? I got you out of there. Probably Austin would've, if he was there, just the same, but it's my fault since I did it and he didn't have to, you understand me?"

Most guys wouldn't. Not half. But he'd lived with Marie. "Yeah," he said, and struggled to sit up, with a hand pressed against his forehead, because his brain hurt.

"So I'm sorry," Christian said. "Bad start. Austin pounded meagainst a wall. And he didn't pass the warning to all the guys. The ones that pounded you, they won't, twice. They'll walk wide of you, and me. I have it over them in spades right now. They'll do me favor points, you, too, if you don't make a case. Rough guys, but they know they're on notice."

"I won't be anybody's target. Not anybody's. Not theirs. Not yours."

"I said I was sorry. I'd had my own run-in with Austin, all right?—There's a shower. Clean clothes. Couple of days yet before jump and then you can lie still and let it heal. You'll be fine. Won't even scar."

Christian could say that. But a shower was attractive. Realattractive. Clean clothes… it felt as if the coveralls had grown to his skin. He'd sweated in them. He'd bled over them. He loathed the feel of them. And the loan of a shower and clean clothes… was a bribe worth a peace treaty, far as he was concerned. He started to get up.

"You make it on your own?" Christian asked.

"Yeah," he said, and hauled himself up, one hand on the wall.

A little dizziness then. But his sight was mostly back. He got up in the unaccustomed great space of the biggest junior officer's cabin he'd seen, and wobbled back to the shower.

Forgot the clean clothes. He turned around to trek back again, but Christian brought them to the bath and left him alone, afterward, to knock around the small mirrored space, getting undressed.

After that was warm water vapor, luxury detergent, the kind-to-abused-skin sort, and he could have sunk to the bottom of the shower and stayed there a year, but it had an auto-cycle he hadn't set right and it went to blow dry long before he wanted it.

He opened the door a crack and snaked an arm out for the clothes, such as they were. He'd never tried skintights. Never had the budget and never wanted the cousins laughing at him.

Black. Shimmer-stuff. Damned little left to the imagination, one size fit all, or you definitely shouldn't think about it.

He hadn't a mirror inside the shower and he wasn't at all sure, except they were clean, dry, more comfortable than they looked, and the shirt—blue—at least was tunic-style. Tabs at the side that made the waist fit—another one-size, and the loose sleeves, anybody could wear who didn't have arms to their knees. He wasn't sure. He felt like a fool coming out of the shower, and stopped in the doorway for a mistrustful glance at the mirror.

"Better," Christian said, "A little style, Hawkins, couldn't hurt."

Heat from the shower hadn't made him steadier. He wobbled. He glared at this implied deficiency in Hawkins taste. He stuck his foot in his boot in the doorway, and leaned on it, working the heel on while he braced a hand against the wall.

"So you want off this ship," Christian said.

Escape? A deal with Christian? No way in hell did he trust it. He balanced and shoved the other foot in the other boot.

"This is a true or false. Possible even for a Hawkins. Fifty percent chance of being right. Do you want off this ship?"

Christian might want rid of him. That part he could believe, the way he couldn't readily believe Christian's stepping into a brawl only to save him. He didn't know how obvious his suspicions were, or what it could cost him to challenge Christian with the truth. But he decided on confrontation, for good or for ill. "Not to any Mazianni carrier, if that's the trade you're in."

"Yeah, yeah, we just load up the fools and Mazian pays top price, loves to buy those fools. Use your damn head. Where are we going?"

"Pell's what I've heard."

"Not a bad place to ship from. Civilized port. Lot of ships. Go where you like. Can't beat that."

Christian left a silence in which he might be expected to say something. He didn't. He didn't trust anything about the offer, didn't trust Christian's motives—

"Look," Christian said. "Sit down. " Christian indicated the end of the bed, and reluctantly, because his knees weren't that steady, he went back to the bed and sat. "You may have noticed," Christian said, leaning against the wall near him, one booted ankle over the other, working the heel back and forth, "that Austin is a difficult sod. I said we hadn't an auspicious beginning. Much less so with maman, Beatrice, who doesn'tlike your presence. We are the victims of two ferocious women, one of whom wants to kill us and the other of whom wants to kill you before you kill us."

"I've no desire whatever—"

"I'm perfectly certain you're an independent and difficult spirit, yourself, but maman, understand, Beatrice… will absolutely not tolerate you on this deck, not as Marie Hawkins' offspring, certainly not as Austin's, competing, shall I say it, with me? Shall I say plainly that Beatrice wants you out of here, you most certainly want to go… and it seems to me that you have no evidence against us, nothing but a merchanter quarrel,—and we all know how quickly stations wash their hands of our untidy affairs. I would never tie myself up with station police and lawyers, on the Alliance side of the Line, lawyers and court dates and station law—you don't like station lawyers, do you, Hawkins? You're not that crazy."

"No."

"Not going to be that crazy."

"No."

"Pell has customs. But you've got your passport…"

God. They wouldhave it. Withhis papers, that said he worked computers.

"—Found it on you. No problem. Just get you out the airlock all legitimate and you take a walk."

"And end up dead."

"Hawkins. Hawkins. I had my chance in the warehouse. But the fact that you're, realtime, my slightly olderbrother, suggests to certain members of this crew that you might find a niche aboard, that you might pose some threat to interests that have worked a long time to secure the positions they have, do you see? Not that I'm immune. I could rather like you, as a human being. You have certain engaging qualities, occasional flashes of actual intellect, you don't know the depth of dimness I have to deal with in the crew, God! you'd be such a relief! But I'm not about to see you become a focus of dissension, or find partisans. This is a rough crew. We manage very borderline individuals. We simply can't afford anyone challenging an officer's authority, do you see? So for various reasons, and peace with maman, who is our chief pilot, far more essential than either of us, and a perfect bitchwhen she's taken a position, I'm perfectly willing to have you disappear at Pell."

"And if something goes wrong?"

"If something goes wrong you end up back aboard. Or with the Pell cops. Choose aboard, is my advice. You wouldn't like the cops."

No spacer liked the cops.

This spacer didn't like the idea of being shanghaied into another crew, either.

And it scared him that Christian's logic halfway persuaded him.

"So?" Christian said. "Deal?"

He shrugged. He'd had a lifetime of Mischa ducking questions, apologizing his way past personnel decisions. He didn't like the taste it left in his mouth. Didn't like what this maneuver implied about Christian's style of command. 'We can't afford anybody challenging an officer's authority. ' Hell.

So Christian helped him escape?

"Yeah," he said, not daring, not wanting to say anything that could change Christian's mind. It wasn't for him to critique whatever got him back to Sprite.

Christian got up.

"Better get you back," Christian said. So the deal seemed done.

—v—

OLDER BROTHER WAS THINKING ON the way back to the brig. Older brother was limping, too—the guys had exceeded suggestions, and that was a problem. "Tell anybody that asks," Christian said, "that it was me that gave you the black eye."

"Is it black?"

"It will be."

Damned odd, Christian thought, everything was so placid of a sudden. They came to the brig, and he figured then that all the rules still applied, in Austin's book, and therefore in his, no matter that older brother wasn't in fighting form. "Cable," Christian said, and Hawkins went inside, picked it up off the floor and locked the bracelet on his own wrist. "Let me see it."

He shut the grid. Hawkins came to the bars and let him inspect the bracelet. The wrist and hand were bruised dark, ugly and painful looking. And the lock was solid.

"Yeah," he said, thought about offering to change hands with the lock, but, hell, they weren't a charity. He started off down the corridor, to leave older brother to his own amusement, or to get to sleep, or whatever, but it occurred to him then that there were reasons security might lock down tight after the rumors got topside, lock down in ways that would screw everything. Besides, older brother might do something entirely stupid if Austin came down in Austin's morning to check on the rumors that were bound to get started—he didn't trust Jamal's discretion or Tink's to hold them off five minutes longer than it took a casual mention to get up to the bridge.

So he went back to the bars, leaned there. Hawkins had sat down on his bunk.

"Hawkins. A warning. If our mutual papa says you're scum, say yes, sir, thank you, sir. That's all. No matter what."

Hawkins' jaw set. You could see the muscle clench. "Man's an ass."

"Hawkins. A small touch of sanity. You're already on scrub. You want to find yourself working four shifts on scrub? No sleep? That's your choice. You keep your mouth under control."

A moment of surly silence.

"Son of a fool bitch," he said, "I'm trying to get you out of here. I'm trying to save your ass. Can we have a yes out of the savee? Can we have a thank you, just a trial run?"

Hawkins kept glaring at him. Didn't trust him, and properly so. But then Hawkins said, "Yeah. Thanks."

"Mouth, Hawkins-brother?"

"Yeah. " Hawkins dropped his stare, at least. Tucked a foot up under the other leg and winced. "I hear. I understand you."

"Easy to pronounce, please and yessir. Get you out of a lot of situations."

Hawkins didn't say a thing.

"Damned fool," Christian said with a shake of his head, but he knew the look, he saw it on Austin, he saw it in mirrors when he'd had a run-in with authority. He withdrew his arms from the bars and went on down the corridor with his own blood pressure up, and with an intense urge to do bodily harm to Hawkins before he got off this ship.

So it didn't make sense that the bloody mess the guys had left Hawkins in should turn his stomach queasy, or make sense that the bruises he'd left had touched the same nerves. He'd seen worse. He'd probably done worse, he didn't keep count.

Didn't know why, when he got up to the bridge and went through his initial shift-change checks—an hour late—he kept flashing on that parting argument and Hawkins' bruises—his fault—and how, just quite strangely, in a ship full of hire-ons you couldn't trust and a handful you knew you could rely on to guard your back, he had an instant expectation of Tom Hawkins' behavior, the body language, the way he worked, an expectation what he was thinking and what it took to get him off a point he wanted to hold…

But, dammit, he had no choice.

He walked the aisles, monitored their course. They'd been lazing along for a full run of the clock in the dark of Tripoint, eating, sleeping, checking and fixing and maintaining. Midway through his watch they'd do a long burn, no traffic problems here, get up to speed on their outbound vector toward Pell.

After which it was Austin's watch, and Beatrice would take them through. He managed the shift, when the number one crew was off… he set up the numbers and the number one crew ran them. Routine, this place, this nearest mass that was nothing but a radiating black lump in the starry dark. The techs were hewing to a long-established procedures list, for this precise place.

"Got it. Thanks. " He signed a check-sheet, meaning the bridge hadn't blown up an hour-thirty into the watch.

The techs around him were in danger of falling asleep of boredom—a contagious condition. Mainday shift on an alter-day ship only punched buttons and checked readout. And stayed ready for the instant of absolute terror that could be an inbound rock. It did happen. Or an inbound and oncoming ship. With Marie Hawkins possibly on their tail—who knew what was a possibility?