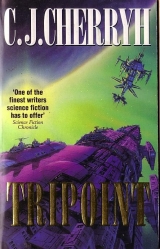

Текст книги "Tripoint "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

"Not this spacer," Capella said. "Was your trail that immaculate?"

"Chris-tian."

He thumbed the com up. "Yessir, I hear you."

"Do you want to come aboard, Christian?"

No shouting. No cursing. Panic hit him. He wanted Austin to yell at him, swear at him, just simply bash him against a bulkhead and beat hell out of him. He'd never heard Austin so calm about something he'd done.

No, he didn't want to come aboard. He wanted to take a bare-ass walk in deep space rather than come aboard.

"Yessir," he said past the obstruction in his throat. He threw a condemned man's look at Capella, an appeal to the living. "Organize a search. Find him. Get him back."

"With what promises?" Capella hissed. "A pay raise? Promotion to tech chief?"

He couldn't stay to argue. Capella was his only hope. He mounted the long ramp, got his wave-through from customs, and walked the tube to the airlock.

Austin didn't meet him there. The inner lock was shut– optional, and Corinthiangenerally opted, not relying wholly on ' station security. He coded through into lower main. Austin was standing down by ops, waiting with arms folded.

"Sir," Christian said when they were face to face. He still expected Austin to hit him.

"Where's your brother?" Austin asked him.

"I don't have a—" The answer fell out, faster than he wanted. He shut up. Austin waited.

And waited.

"He was trouble," he said to Austin's steady stare. "He'd be trouble. He's too scrubbed– clean, he'd find out we're not and he'd go straight to the cops, some time we'd never know it."

"So?" Austin said. And waited.

"I set it up with Martin, down the row. Trip to Sol. They'd leave him there. He'd stay gone."

Another silence, the longest of his life. "I have a question," Austin said finally.

"Sir?"

"Who appointed you captain?"

"Nobody. Sir."

"Who told you your judgment was more important than mine?"

"Nobody, sir."

Another silence. He'd never dealt with Austin in this mode. He'd never seen it in his life. He didn't want to see it again.

"This ship doesn't agree with your judgment, then."

"Nossir. " He saw himself busted to galley scrub. For years. He saw Austin selling him to the Fleet. Beatrice wouldn't like it. But Beatrice herself might be on the slippery slope with Austin right now.

"I have a suggestion," Austin said.

"Sir. " He asked what Austin wanted, he did what Austin wanted. He only hoped to stay alive. Hitting him would have blown off Austin's temper. He prayed for Austin to hit him and call it quits. This… didn't promise forgiveness. Ever. No confidence in him. Ever again.

"I want you to go out and find him," Austin said softly. "I want you to get him back here without tripping any alarm. What are we agreed to with Martin?"

"Ten thousand c."

"You paid it?"

"Yes, sir. " It was the only defense he could claim. "My money."

Austin only nodded. "You'd better get out there."

"Yessir," he said, paralyzed.

"So why are you standing there?"

"Yessir," he said, and backed off a pace before he dared turn and make for the lock, feeling Austin's stare on his back all the way.

Chapter Eight

—i—

AUSTIN WAS ASKING HIMSELF BY NOW whether he needed a son. Asking himself maybe what Beatrice had had to do with the older brother affair. Or what Capella had done.

Guilt was a contagion. That was what Christian discovered. No one of his associates was going to thank him for what he'd involved them in. He couldn't even find most of them.

He walked the docks with no notion in this star system or the next where it made sense to look, or where a fool with a forged passport was going to run. He hadn't caught up with Capella, who, for all he knew, was lodged in some sleepover with a stranger she'd yanked off the docks, the hell with him, Tom Hawkins, and the mess he'd made… she'd raided the safe for him, she'd told him he was out of his mind, and if Capella caught hell from Austin, she knew how to pass it along. No Capella. No Michaels. Nobody answered his pages. He'd thought at least he could rely on Martin'screw to join the search. Martin'scaptain having ten thousand of his money, it ought to buy something.

But Martinwas pulling out of dock on schedule. The same reason he'd picked Martinwas taking that resource out of reach.

He couldn't go to the police. He thought of excuses… he could say he'd forgotten to give his brother his passport and if the fool would just go along with it… but you couldn't rely on Hawkins taking the cue and keeping his mouth shut. Hawkins wouldn't benefit from ending up in the hands of the police, but Corinthianwould benefit far less, and Austin would skin him alive. With salt and alcohol. He didn't want the cops. God, he didn't want the cops—or the customs authorities.

He'd searched every bar in running distance. He'd checked public records. He'd checked sleepover registers. He'd put a page on the message system: Tom, call home toCorinthian. We have a deal.

But the son of a Hawkins bitch wasn't buying.

He didn't want to call a general alarm with Corinthiancrew, over what was bound to be scuttlebutted as his fault. The rumor had to be going around. There hadn't been any witnesses to that scene in lower main, but something was going to get out, and the whispers were going to run behind him for years, he knew they were. Bad enough as it was, if he somehow could retrieve the situation—and Hawkins.

But it looked grimmer and grimmer.

Then he did spot a familiar backside. A shock of blond, spiked hair. A familiar swing to the walk.

"Capella!"

Said swinging walk never interrupted at all. He sprinted, overtook, grabbed an elbow. Gingerly.

"Not a sign," Capella said darkly. "Not a perishing sign. And I've called in favors."

Favors where Capella knew them might involve cages they didn't want to rattle. Very dark places indeed.

"I've been out for two fucking days, Pella, I've been top to bottom of the station, I've been through records, I've been in the bars, I've been through computer services, I've put messages on the station system. I've looked in station employment and the spacer exchange. I'm out of places to look."

"You look like hell."

He rubbed an unshaven face with a hand that felt like ice. Tried to imagine what he was going to do or say if he didn't find Tom Hawkins at all. Or if he couldn't claim to be in command of the crew that did.

"When'd you eat last?" Capella asked.

He didn't know. He shook his head. Remembered bar chips. A drink. God knew when. He hadn't slept. Hadn't showered. Hadn't shaved. Hadn't stopped walking in hours.

"Come on," Capella said, and steered him for the frontages.

"We haven't time. Pella, if we don't find him…"

"Yeah, your ass is had. You just did us all such a favor. Come on."

"Austin's going to kill me."

"Chrissy-sweet, I'm going to kill you, if captain-sir tosses us both off the ship, damned right I am. " Capella didn't give up his arm. She steered him into the dark of one of Pell's 'round the clock bars, into a vibrational wall of beat and light and music. He all but turned and walked out, confused by the input, except for Capella's governing hand on his arm. Capella walked him up to the bar, tapped the counter in front of the barkeep with a black fingernail. The bracelet of stars glowed green. And the barkeep looked up with a stark, hard stare.

"Man wants something edible," Capella said, "before he falls over. Can do?"

"Done," the barman said, and shoved crackers at them. "Stew coming. What are you drinking?"

"Vodka and juice for him," Capella said. "Rum for me. Scanlon's."

"You got it," the barkeep said.

His knees made it to the table next the bar. He sat down. Good thing there was a chair under him.

Capella settled opposite. Folded her arms. Stared at him dead-on.

"We have got to find that son," Capella said. "Think, dammit!

Where would he go? Is he religious? Has he got a kink? A vice? Has he got friends here?"

"No.—Hell, I don't know. How would I know?"

" Spriteever trade here?"

"No. I'm sure of that."

"No business contacts. No companies with offices in places they do trade. Banks. Outfitters. Insurance companies. Religious organizations."

"I don't know! How could I know?"

"You could have asked him. You might have been curious. You might have wondered before you chucked him off to Martin. "

"Don't accuse me!"

The barman brought the drinks. Capella handed over her crew-card. "Put standard on it. I do math. Thanks."

"He's got two hundred," Christian said.

"Two hundred what?" Capella asked.

"Two hundred in chits! I wasn't going to turn him out broke! He's got two hundred in hand. A fake passport. " He got a breath. The air was cold, sullen cold, all the way to the center of his bones. He could admit, at least, the rest of his disgrace. " Martin'sgot ten thousand."

Capella hadn't expected that. Clearly. She sat for a moment, then shook her head and gave a whispered whistle. "Shit-all. What've you got left here?"

"Five. Five to my name, Pella. I didn't want to kill him!"

You never knew, with Capella, how anything played, or whether she thought you were sane or crazy. She sat staring for a moment and finally shook her head, looking away from him as if that much insanity was too much for her.

In her universe. In his. In Beatrice's. In Austin's. He didn't know. He just never understood the rules. He never had. He got one set from implication and another set from Austin's expectations, and Beatrice's, and another still from Capella's, and he just never understood the way to fit them together.

"Christian," Capella said, then, and took his hand in hers, on which the bracelet of stars glowed as independent objects. "We'll look. All we can do. We'll look, and I'll call in a couple more favors. I don't know what more we can do."

"Austin's going to kill me."

"Yeah. I do wish you'd thought about that. But in realspace we play with real numbers, don't we?"

Chapter Nine

—i—

PEOPLE CAME AND WENT, tens and twenties the hour, and there wasn't a place to sleep, except the public restroom, as long as nobody came in. He had the 200c… but he didn't dare go outside the area or use up his cash. He didn't know the station, didn't know the rules, didn't know the laws or what he could get into or where the record might be reporting. When you ran computers for a livelihood you thought of things like that sure as instinct, and Tom personally didn't trust anything he had to sign for. You didn't, if you wanted to avoid station computers, use anything but cash.

At least Christian's money wasn't counterfeit. At least Corinthianhadn't reported him to the cops. And he'd gone for the one place on Pell he knew he might find a friend… straight to the botanical gardens Tink said was on his must-do list every time he got to Pell.

The gardens, moreover, were a twenty-four hour operation… tours ran every two hours, with the lights on high or on the actinic night cycle, even in the dark, by hand-held glow-lights. Hour into hour into shift-change and shift again, he watched the tour groups form up and go through the glass doors. He watched people go through the garden shop, and come away with small potted plants. He shopped, himself, without buying. He knew what ferns were. There were violets and geraniums aboard Sprite, people traded them about for a bit of green; and Sprite'scook raised mushrooms and tomatoes and peppers in a special dedicated small cabin, so he understood plants and fungi and spices.

He had more than enough time to sneak a read of sample slide-sets and even paper picture books on the shop stands and to listen to the public information vids. He learned about oaks and elms, and woolwood; and how buds made flowers and how trees lifted water to their tops. It kept him from thinking about the police, and the ache in his feet.

But every time new people arrived through the outer doors, he dropped whatever he was doing and went furtively to look over the new group, dreading searchers from Corinthianand hoping anew for Tink, scared to death that during some five minutes he had his eye off that doorway he was going to miss Tink entirely.

So supper was a bag of chips from a vending machine and breakfast the next day was a sandwich roll from the garden shop cafeteria, because by then he was starved, and he'd held out as long as he could.

He skipped lunch. He figured he'd better budget his two hundred, as far as he could, against the hour the director's office or the ticket-sellers or gardeners or somebody noticed him hanging around and began to suspect he was up to no good.

Meanwhile he tried to look ordinary. He didn't spend more than an hour at a time in the shop. He walked from place to place, browsing the displays, the shop, the free vid show. He lingered over morning tea in the cafeteria, where he could watch the outside door through its glass walls, and drank enough sugared tea, while he could get it, that the restroom was no arbitrary choice afterward. He constantly changed his pattern in sitting or standing. He didn't approach people. If they spoke to him he was willing to talk, only he had to say he was waiting for a group, and claim the truth, that he hadn't had the tour, but, yes, he'd heard it was worth it. Once a ticketer did ask him could he help him, with the implied suggestion that he might move along, now, the anticipated crack of doom—but his mind jolted into inventive function, then, and he said he'd made a date and forgotten when and he didn't want to admit it to the girl. So he meant to stand there until she showed. He was desperate. He was in love. The ticketer decided, evidently, that he was another kind of crazy, not a pickpocket or a psych case, and shot him tolerant looks when he'd look toward newcomers through the doors. He'd mime disappointment, then, and dejection and walk away, playing the part he'd assigned himself without much need for pretense.

That bought him off for a while, he figured. But he also took it for a warning, that if it went on too long the ticketer was going to ask him again, and maybe put somebody official onto him.

So he embroidered the story while he waited. He was desperately in love. He'd had a spat with the girl—her name was Mary. He couldn't call her ship. She was the chief navigator's daughter and her mother didn't like him, and now he couldn't find her. But he thought she might be sorry, too, about the fight. He thought she might show up here, to make up. He borrowed shamelessly from books he'd read and vids he'd seen. She had two brothers who didn't like him either. He thought they'd told her something that wasn't true, that started the fight… well, he hadmissed their date, but that was because he'd gotten a call-back to his ship and he couldn't help it, and he'd tried to call her, but he thought her mother hadn't passed on the message.

"No word yet?" the ticketer would ask him.

And once, "Son, you ever think of sleep?"

He looked woebegone and shook his head. It didn't take acting. He was so tired. He was so hungry. He watched the tour groups gathering and going in, he watched the young lovers and the parents with kids and the spacers on holiday and the old couples who came to do the evening tour. He saw the amazing green and felt the moist coolness from the gardens when the doors would open, cool air that wafted in with strange, and wonderful scents. You could do a little of it by computer. You could walk in a place like that. You could even get cues for the smells and hear the steps you made, on tape. But the brochure—he'd read every one, now, in his waiting, from the selection they had in the rack—said that it was unique, every time, that it changed with seasons, that it could put you in touch with the rhythms of Earth's moon and seas.

He stood outside the vast clear doors, and turned back again when they shut, and went back to his waiting, figuring maybe Tink had business to do first, and wouldn't come here until maybe tomorrow.

He didn't know. He was hungry and he was desperate. He thought (thinking back into his made-up alibi) that he might pretend to be some total chance-met stranger calling in after Tink, and maybe get a call through Corinthian'sboards and out to him through the com system, but maybe they'd suspect, maybe they had a voice-type on him and they'd figure he might try to contact Tink and they'd come up here and haul him away with no chance of making a deal.

Hunger, on the other hand, he still had the funds to do something about. He splurged a whole 5c on a soup and salad, I which was astonishingly cheap on Pell, especially here, where green salad was a specialty of the restaurant.

It looked good when they set it in front of him. He didn't get it often enough. The soup smelled wonderful.

He'd only just had a spoonful of the soup when he saw, the other side of the glass, coming in the doors, a dark-haired woman in Corinthiancoveralls.

He let the spoon down. He ducked his head. His elbow hit the knife and knocked it off the table. On instinct he dived after it, as a place of invisibility.

He straightened up and didn't see her. Presumably she'd gone to the gathering area, just past the corner. He turned around to get up.

Stared straight at Corinthiancoveralls. At dark hair. At a face he knew.

"Ma'am," he said, compounding the earliest mistake he'd made with Saby.

"Mind if I join you?"

He was rattled. He stumbled out of his chair, on his way to outright running, and ended up making a sit-down-please gesture. He fell back into his seat, thinking she was surely stalling. She'd probably phoned Corinthian.

"Have you called them?" he asked.

Saby didn't look like a fool. He could be desperate enough to do anything, she couldn't know. He saw calculations go through her eyes, then come up negative, she wouldn't panic, she knew he might be dangerous.

"Not yet," she said. It had to be the truth. It left him room to run. "I hear you didn't like Christian's arrangements."

"I don't trust him," he said. "Less, now."

"The captain wasn't in on it."

"I never thought so," he said.

"Christian's in deep trouble," Saby said. "Have your soup."

"I'm not hungry."

"Listen. The captain wants you to come back. The passport's a fake. There's just all kinds of trouble. There's some real nice people who could get hurt."

The waiter came over, offered a menu.

"Just coffee," Saby said. "Black."

The waiter left. Tom stirred his tea with no purpose, thinking desperately what kind of bargain he could make, and thinking how it was a ploy, of course it was. But a captain had a ship at risk because of him, a ship, his trade, his license, all sorts of things.

Which meant once Saby made that phone call, all hell was going to break loose, and they'd take him back, they'd takehim back, come hell or station authorities. Couldn't blame anyone for that. Any spacer would.

"He'd really like it if you'd come back," Saby said.

"Yeah," he said. "I guess he would."

"I don't think he'd have you on scrub anymore."

"I like scrub fine. It's good company."

"We don't want trouble."

"I know you don't. I don't. Just give me my passport and you won't hear a thing from me."

Saby looked at the table. The waiter brought the coffee. She sipped it, evidently satisfied. "So why did you come here?" she asked him, then.

"I heard about the gardens. It was a place I knew to go."

"I didn't plan to find you. I just happened here.—But if I called the ship, you know, if I told them you were coming back, I think it would make them rethink everything. I don't think you'd end up in the brig again. I really don't."

"I get to be junior pilot, right?"

"I don't think that."

"It's not a damned good offer."

"What do you want?"

He didn't know. He didn't think any of it was true. He shook his head. Took a spoonful of cooling soup.

"Well," Tink said out of nowhere. Torn looked up. "They're looking for you, " Tink said.

Last hope. A ball of fire and smoke.

"Did you tell her?"

"Tell her what?" Tink asked.

"That I'd be here."

"I didn't know you'd be here," Tink said, sounding honestly puzzled.

It was too much. He shook his head. He had a lump in his throat that almost prevented the soup going down.

"Tink was going to the gardens," Saby said. "He always does. I said I'd meet him here."

"Not like a date or anything," Tink said, sounding embarrassed. "She's an officer."

"Tink's a nice date," Saby said. "Knows everything there is about flowers."

"I don't," Tink said.

He'd been caught by an accident. By the unlikeliest pair on Corinthian. Nothing dramatic. Tink and Saby liked flowers. What was his life or what were his plans against something so absolutely unintended?

"Call the ship," he said. Tink clinched it. He didn't want the cops. He didn't want station law. "Tell them… hell, tell them you found me. Say it was clever work. Collect points if you can get 'em."

"You seen the gardens?" Saby asked.

He shook his head.

"You like to?" Saby asked.

Of course he would. He just didn't think she was serious.

"You got to," Tink said. And to Saby: "He's got to."

"You want to?" Saby asked.

"Yeah," he said.

"You through?" Saby asked, and waved a hand. "Finish the salad. We've got time."

"Good stuff here," Tink said. "We're taking on a load of fresh greens. Tomatoes. Potatoes. Ear corn. Goodstuff…"

He'd only gotten potatoes and corn in frozens. He thought about the galley. About Jamal. Ahead of Austin Bowe, damned right, about Jamal, and Tink. A homier place than the accommodation his fatherassigned him. The pride Tink had in his work… he envied that. He wanted that. There were things about Corinthiannot so bad.

If one had no choice.

"You want to go the tour, then?" he asked Saby. "I swear I won't bolt. I promise. I don't want you guys in trouble."

"No problem," Saby said. "I give everybody one chance."

He shoved the bowl back. Half soup. Half salad. He hated to waste good food, especially around Tink. But he didn't trust more Corinthians wouldn't just happen in, on somebody's phone call, and it had gotten important to him, finally, to see the place' he'd seen beyond the doors, the path with the nodding giants he thought were trees. He'd heard about Pell all his life, some terrible things, some as strange as myth. He'd not seen a Downer yet. But he imagined he'd seen trees, in his view through the doors.

And if he'd only a little taste of Pell… he wanted to remember it as the storehouse of living treasures he'd heard about as a kid. He wanted the tour the kid would have wanted.

Didn't want to admit that to his Corinthianwatch, of course. He thought Tink was honest, completely. But he wasn't sure Saby wasn't just going along with anything he wanted until reinforcements arrived.

"I got a phone call to make first," Saby said.

"Yeah," he said. "I guess you do."

He was surprised she was out in the open about it. It raised his estimation of Saby, and made him wonder if she had after all come here, like Tink, with Tink, just to see the trees.

He watched her walk away and outside the restaurant. He went to the check-out and paid the tab, in cash. He went out with Tink, toward the ticket counter, finally.

"Let me get the tickets," he said to Tink. "It's on my brother. He gave me funds."

Tink didn't seem to understand that. Tink seemed to suspect something mysterious and maybe not savory, but he agreed. Tink looked utterly reputable this mainday evening, which was Tink's crack of dawn morning—wearing Corinthian-greencoveralls that hid the tattoos except on his hands. His short-clipped forelock was brushed with a semblance of a part. He had one discreet braid at the nape. Most men looking like that were looking for a spacer-femme who was also looking. Not Tink. And he understood that. At twenty-three, he began to see things more important than the endless search after encounters and meaning in some-one. Some-thing began to be the goal. Some-thing: some credit for one's self, some achievement of one's ambitions, some accommodation with the illusions of one's misspent childhood.

Saby came back from her phone call, all cheerful, her dark hair a-bounce, mirth tugging at the corners of her mouth. "The captain says about time you reported in. I told him you were waiting to take the tour. He said take it, behave ourselves, and we're clear."

"He said that?" He didn't believe it. But Saby didn't look to be lying. She was too pleased with herself.

"Come on. Let's get tickets."

"Got 'em," Tink said.

"Christian's compliments," he couldn't resist saying. "His money."

Saby outright grinned. And pulled him and Tink, an elbow apiece, toward the staging area.

—ii—

IT WAS ROSES TINK FAVORED. But trees and the concept of trees loomed in his mind and forever would, palms and oaks and elms and banyans and ironhearts, ebony and gegypaand sarinat. They whispered in the fan-driven winds, they shed a living feeling into the air, they dominated the space overhead and rained bits and pieces of their substance onto the paths.

"If a leaf's fallen," the guide told them, "you can keep it. Fruits and flowers and other edibles are harvested daily for sale in the garden market."

Leaves were at a premium. Tourists pounced on them. But one drifted into his reach, virtually into his hand, gold and green.

"You can dry it," Tink said. "I got two. And a frozen-dried rose."

"The hardwoods come from Earth," the tour guide said, and went on to explain the difference between tropics and colder climates, and how solar radiation falling on tilted planets made seasons—the latter with reference to visual aids from a tour station. First time the proposition had ever made sense to him.

Then came the flowers, in the evolution of things, the wild-flowers and finally the ones humans had had a hand in making… like Tink's roses, hundreds and hundreds of colors. Individual perfumes, different as the colors. The reality of the sugar flowers. The absolute, sense-overwhelming profusion of petals.

It smelled… unidentifiable. There was something the scent and the assault of color did that the human body needed. There was something the whole garden did that the human body couldn't ignore. He forgot for a minute or two that he was going back onto Corinthian, and that if things had gone differently he might have had a hope of his own ship.

But that might come around again.

There might be a chance. There might be…

Fool's thought, he told himself, and felt Saby's hand on his arm, and listened to Saby talk about the roses, and the jonquils and iris and the tulips and hyacinths. Figure that the cornfields and the potatoes were much more important, yielding up their secrets to the labs as well as supplying stations and spacers direct…

Interesting statistics about the value they were to humankind. About human civilizations riding botanical adaptations to ascendancy.

But less inspiring than the sensory level… and he was glad that the tour wended its final course back to the whispering of the tall trees, back to that sweet-breathing shadow. His legs ached from walking. Felt as if they'd made the entire circuit of the station.

Maybe they had. But he took the invitation the guide offered, to linger a moment on the path. He didn't want to go out, where, he'd been thinking the last half hour, a whole contingent of Corinthiancrew must be waiting for him.

Maybe Christian, too. Probably Christian—madder than hell.

But a ship was a place. A station wasn't, in his book. He'd had his taste of dodging the station authorities just trying to evade questions from the botanical gardens staff. He didn't want to do it dockside and in and out of hiring offices, trying to stay out of station-debt, which, if he got into that infamous System… no.

Which meant a return to Corinthianwas rescue, in a way, and he was willing to go. But he didn't want to lose the souvenir leaf—the garden was a place he wanted to remember and wasn't sure he'd see again. So, fearing a little over-enthusiasm on the part of the arresting party he was sure was waiting, he asked Saby to keep the leaf safe for him. "Sure," she said, and slipped it into her sleeve-pocket.

So the tour was done, and he walked out with Tink and Saby.

Didn't find the reception party—and he was so sure it existed he stopped and stood in the doorway, looking for it.

"She's a pretty one," the ticketer at the door said—to him, he realized then, and then, in the racing of his bewildered wits, remembered the lie he'd told, about waiting for a girlfriend.

"Yeah," he said, and only wanted to get out of there before some other remark started trouble, but Saby laughed, took the cue and hooked her arm into his, steering him away and on, toward the doors.

"Tink," she said, "it's all right. You don't know where we are. Right? We'll make board call. Captain's orders."

Tink didn't look certain about that. Hewasn't certain about this 'don't know where we are' and 'captain's orders'… not that Saby was likely to use physical force. But Saby clearly had the upper hand in the information division, and hecould be in deep trouble, for all he knew, headed for one more ship like Christophe Martin.

Tink said, looking straight at him. "Tom,—if she says it's so, it's so. If she says do, you do it. All right? Is that all right?"

Tink meant it. Tink meant it a hundred percent, like a nervous mama turning her kid over to a stranger she almost trusted, and he had it clear who was in what role in Tink's book: if he did anything Saby could complain of, Tink was going to find him, he had no question.

"Yeah," he said, and meant it. "No problems. I wantto go back to the ship. I'm willing to go. " It finally occurred to him to say that, and he thought at least Tink would believe him.

"Come on," Saby said, tugging on the arm still linked with hers, and he had the momentary, panicked thought that if anything happened to Saby, if any remote, unpredictable accident happened to Saby Perrault, he was a dead man, not alone in Tink's book, but with the rest of Corinthian, the same law that, had brought Sprite'screw to Marie's defense, however belated, the same that defended every merchanter on dockside and made, stations skittish of any challenge to ship-law, if two ships decided to settle a problem, or if, however rarely, a spacer disappeared off a dockside. Saby could call down all of Corinthian, hire-ons the same as born-crew, he got that clear and clean from Tink.