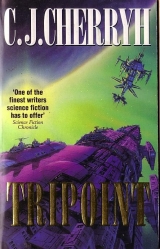

Текст книги "Tripoint "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Meaning that trim-ups might be rare when a long-hauler was following the computer-directed approach—no pilot flew docking by the seat of the pants—but stations were debris-generators, thick with maintenance and service traffic and escaped nuts, bolts and construction tiles, and, while in the zone of greatest risk a freighter pilot was no-stop, come hell or the Last Judgment, or absent anything but damage to the docking apparatus (meaning any pusher-jock in a freighter's approach path was a bump and a noise and a gentle course-correction), the possibility of evasive maneuver did exist. That meant the children battened down in the cushioned Tube in the loft, in which they could take most any vector-shift; and crew off and on duty found themselves a definite place to Be for the duration.

Which in Marie's case was her office; and in a junior computer tech's, it was the bridge. Load the file, wait for the check, load another file, wait for the check.

It left too much time for said junior tech to think, between button punches, in his lowly station sandwiched in with seven other cousins at the tail of the bridge.

It left too much time to rehearse the session with Mischa, and the one with Marie, comparing thosemental files for discrepancies, too, but you never caught them out that easily. They didn't outright lie in nine tenths of what they told you. They were brother and sister. They had grown up conning each other. They'd learned it from each other if nowhere else. And they were good at it. He wasn't.

Heredity, maybe. Like the temper Mischa said did him no favors. He was, if he thought about it, scared as hell, figuring Marie wasn't done with double-crosses. Marie didn't trust him.

And, when it came down to the bottom line, Marie would use him, he knew that in the cold sane moments when he was away from the temptation she posed to think of her as mama and to think he could change her. Get that approval (she always dangled) in front of him, always a little out of possible reach.

But nothing mattered more to Marie than dealing with that ship. And if Marie was right and she smelled something in the records that wasn't right with Corinthian—you could depend on it that she'd been tracking them through every market and every trade she could access long-distance—she might have files down there in cargo that even Saja didn't know about. Files she could have been building for years and years and never telling anyone.

Load and check, load and check. He could push a few keys and start wandering around Marie's data storage—possibly without getting caught, but there were a lot of things a junior tech didn't know. The people who'd taught him undoubtedly hadn't taught him how to crack their own security: the last arcane itemswere for senior crew to know and mere juniors to guess. So it was load and check, load and check, while his mind painted disaster scenarios and wondered what Marie was up to.

Supper arrived on watch. The galley sent sandwiches, so a tech had one hand free to punch buttons with. Liquids were all in sealed containers.

On the boards forward in the bridge, the schemata showed they were coming in, the numbers bleeding away rapidly now they were on local scale.

A message popped up on the corner of his screen. At dock. See me. Marie.

—ii—

MARIE LEANED BACK FROM THE CONSOLE, seeing the Receivedflash at the corner of her screen. So the kid was at work. The message had nabbed him.

He'd arrive.

The numbers meanwhile added themselves to a pattern built, gathered, compared, over twenty-four years. How shouldn't they? Corinthianwas what it was, and no ship and no agency that hadn't had direct and willing information from Corinthianitself could know as much about that ship as she did.

She knew where it traded, when it traded, but not always whatit traded.

She knew at least seven individuals of the Perrault clan had moved in from dead Pacer, long, long ago. Pacerhad had no good reputation itself, a lurker about the edges, a small short-hauler that, on one estimation, had simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time… and on another, had entirely deserved being at Mariner when it blew.

She knew that Corinthiantook hired-crew, but it didn't take them often or every voyage, or in great number. Hired-crew skuzzed around every station, most of them with egregious faults—tossed out of some Family, the worst of hire-ons, as a rule, or stationers with ambitions to travel, in which case ask what skills they really had, or the best of them, the remnant of war-killed ships. Sure, there were hired-crew types that weren't out to cut throats, pick pockets, or mutiny and take a ship. But those were rarer, as the War generation sorted itself out.

Mutiny had never taken Corinthian. Which argued for a wary captain, a good eye for picking, or cosmic good luck.

Except that Corinthianrejects never turned up on dockside. And her crew spent like fools when they were in port—certainly hired-crew had reason to want to stay with Corinthian, and could count themselves well paid.

But nobody ever got off. Not that she'd found. Not, at least, in any crew record she'd found… and she'd searched—nothing to prevent any ship in any port from drinking down the hired-crew solicitations, and reviewing the backgrounds they'd admit to: had a program for that, too. And at Viking, where Corinthianhad called frequently (since the second closing of the Hinder Stars, strange to say)—there were no Corinthianex-crew. There might have been hires. But no one let off.

You couldn't be so lucky as to get all saints, all competent, all devoted crewmen.

So what became of the rejects? There was still a commerce in human lives—rumor said; the same commerce as during the War, when the Mazianni had stopped merchanters and impressed crew. Rumor said… some ships that dealt with the Mazianni still traded surplus crew for a fair profit in goods, and therefore hired-crew had better watch what they hired– to.

The lurkers in the dark were certainly still out there. Accidents took ships—rarely, but accidents still happened, and ships still disappeared somewhere in the dark. Couldn't prove that Corinthianin specific had anything to do with those rumored tragedies… but it had to get your attention. You had to realize… if you were in port with the likes of Corinthian, and if they knew you were on their trail… that your odds of accident had just gone higher, too.

You had to realize, if you were the only one aboard who wanted that son of a bitch's hide, that certain members of the Family, less motivated and habitually more timid, would sabotage you, out of concern for their own lives.

So Tom was on her side. And Tom had talked to Mischa.

So Mischa had his spy.

Well, at least that meant walking out of the ship was easier.

—iii—

THE CENTRAL QUESTION, IN TOM'S mind, was how the clearance through customs was going to work—or, at least, how it was going to look.

If Mischa believed he was leaving the ship with Marie on hisbusiness, he'd get the permission fairly easily; but Mischa wasn't supposed to know that he'd told Marie that Mischa had put him up to it, or he wasn't supposed to know that Marie already knew all about it and they'd agreed to go diving in station records.

It was all too damned tangled, and he'd had word from Marie, which might or might not mean Marie accepted him at face value… or that Marie had been in contact with Mischa. He didn't know—couldn't know without asking questions that might bring Mischa and Marie head to head.

So he didn't wait for official clearance to come to him from Mischa's office. He excused himself off duty with Saja, telling Saja that Mischa had said see to Marie, and got Saja's leave to go downside the minute Spritelocked into dock. He shut down his station, left his seat and rode the lift downside, leaving the cousins to wonder—and Saja to ask Mischa was it true, and Mischa to give the permission, granting Mischa hadn't yet figured out that he'd gone over to Marie's camp, and wouldn't be reporting in.

He went to Marie's office, found Marie talking with customs on com, a routine call he'd heard her make since he'd first sat in on her duty station—at six or seven, close to when Marie'd first taken him home. He'd thought all this exchange of numbers and origins and cargo data mysterious and impressive, then; he'd rated it tedious since—but now he listened to it in suspense, hoping for some clue to Marie's intentions and dreading intervention from Mischa at any moment.

But nothing in the conversation sounded unusual, just Marie's easy, crisp way with station officials, all the i's dotted and the t's crossed. Station, at least, showed no indication to them that Viking was in any way nervous about their presence. He didn't hear any word of special security arrangements from station officials, didn't hear any advisement from Marie whatsoever that there was a history between Spriteand a ship already in dock—just a welcome in from station, a little chatter of a friendly nature, a little exchange of names and procedures.

A free port meant no customs to speak of, the way he'd understood the briefing, at least not the usual meticulous accounting of goods carried in. There were rules, mostly about firearms and drug trading, and an advisement that long-haulers would be advised to stay clear of white sector.

Meaning out of the Viking local haunts, he supposed, the territory of Viking miners, dockers, construction personnel, and the occasional citizens who preferred the free and easy atmosphere of dockside to the pricier, fancier establishments above.

In that arrangement, Viking was no different than Fargone, where you didn'tgo into insystemer bars and sleepovers unless you were truly spoiling for a fight.

"We copy that," Marie said. "We're a quiet lot. Thank you. Glad to be here, hope we can be a regular. We need to do some on-site consultation with the Trade Bureau. Can you tell me who to talk to?"

His ears pricked up. A name. Ramon French, Trade Bureau, Union Affairs. Marie made another call, said they'd been called in on short notice, hadn't any Alliance figures, wanted access to the local Trade resource library, in the Bureau, which they'd had word at Mariner that they would be able to access under the new rules. They had to establish an account, had to take care of certain legalities. General crew would exit in about an hour after shut-down, but certain officers would as soon be through customs early so they could get the credit accounts established, could Viking arrange that?

There was a good deal of back and forth after that, on screen, Marie looking for something, the program, he supposed it was, searching at high speed through the records for the patterns it wanted, while Marie talked on the station line with m'ser French, secretary in the Viking Trade Bureau, about accounts, and arranging the data search.

"Good, good," Marie said, signed off, and spun her chair about. "I take it you're coming, Tommy-lad."

"I guess I am," he said, wondering if it was really going to be that simple to get off the ship. But Marie just closed down her boards, led the way down the corridor, and keyed them through the airlock.

He was appalled. You didn't just… openthe lock without the captain's order. But nobody had the lock codes alarmed, evidently. Mischa had to know what Marie was likely to do, and Mischa hadn't ordered any special security.

Which was one vote, he guessed, for Mischa having told him at least a quarter of the truth.

Which might bear on who was telling the rest of the truth… and whether he ought in fact to report back to Mischa. Scary proposition, to be first out of the ship… down the winding access, breath frosting, and out the station lock on the downward ramp.

He'd never gone through customs with Marie before. Maybe the easy attitude he saw in the officers was because Viking had just become a free port, whatever that exactly encompassed. Maybe it was just that senior crew on reputable ships didn't get the once-over and question and warning juniors got in places like Mariner and Fargone. Marie got a wave-through from a uniformed officer, the only one visible, without even a kiosk set up, or a single glance at her papers. She said, "He's with me," and the customs official waved him past with her.

Amazing. He thought he could like being senior crew, if that was what it meant. And Viking might be a grim, utilitarian place, as grim and browned-steel as his childhood memory of this station, but if it meant wave-throughs from customs, and no standing in long lines of exiting crew, he thought he could like Viking port's attitude.

Except for the other clientele.

—iv—

BERTH 19 ORANGE SECTOR WAS moderately convenient to Viking's blue section, where the Trade Bureau maintained its offices, a long walk or a relatively comfortable ride on one of the slow-moving public transports. There was, uncommon on stations Tom was familiar with, plenty of sitting room on the transport benches. You stepped aboard—if you weren't able-bodied you could flag it to a complete stop—and it also would do a full stop at any regular Section Center, but otherwise you just intercepted it when it made one of its scheduled rolling stops, stepped up as you grabbed the boarding rail, and stepped off the same way.

One of those full stops was, of course, the station offices in blue sector. Marie got up, as the stop came up. He waited beside her, hanging onto the rail until the transport slowed down. A crowd was waiting to board, confronting a good number getting off. You could always figure that blue would be the highest traffic area on the station, give or take the insystemer bars at maindark or alterdark shift-change, or the occasional concert or public event: blue held all the station business offices, the administrative offices, the main branches of all the banks, the embassies and trade offices, the big corporate offices, and the station media centers. You saw people in business suits, people in coveralls—half the crowd carried computers or wire-ins, pocket-coms, you could take your pick of accountants and security officers, official types—those usually in single cab-cars that wove in and out of foot traffic, and hazardously close to the ped-transports: step off without looking and you could get flattened.

Heart-stopping, close call, that, just then, cab and pedestrians, human noise of a sort you only heard in places this dense with people. It gave him the willies… just too many people, all at once, going in chaotic directions, not caring if they hit each other. Marie stepped off in the middle of it. He stepped off beside her, his eyes tracking oncoming traffic.

"Straight on," Marie said, as if she'd had an inborn sense where things were—or maybe she'd checked the charts. He hadn't. He really didn't like the jostling and the racket—he'd looked all along the dockside they passed for Corinthianpatches, or for any reaction at all from Marie, as if she'd seen something or might be looking for something other than what she said, but Marie was cold and calm, all business, Marie tolerated people shoving into them, which was steadier nerves than he had, and fell back as the crowd surged toward the stopped transport. He caught his balance as a man shoved him, looked around for Marie as the transport started to roll, with people still trying to grab the rails and board.

Marie was back on the transport.

People shoved past him in a last-moment rush for available deck-space. He elbowed back and tried to catch the boarding rail, but others were in front of him and the transport was gathering speed, faster and faster.

"Marie!" he yelled, knocked into a man in a suit, and into a rougher type, who elbowed him hard. He wasn't interested in argument. He ran, chasing the transport in the wake it made in the crowd, knocked into a woman as they both made a frantic grab for the standing pole on the rear of the transport flatbed. He caught it, and clung to it.

The woman had gone down. Others were helping her up, he saw them diminishing as, having gained the platform, he spared the glance back. He hoped the woman wasn't hurt. He didn't know what else he could have done, and he'd made it.

Wobbly-kneed and out of breath, he excused himself past several pole-hangers on the standing-room-only transport, worked his way up to where Marie was standing, likewise holding to the pole.

She awarded him a cold glance.

"Dirty damned trick," he panted. "I knocked a woman down, Marie! Where in hell do you think you're going? Where's this about appointments with Records?"

"Did I bring you up to be naive?"

"Dammit, you brought me up to tell the truth!"

"That's to me. Don't expect any favors from the rest of the universe. Why don't you jump off at the next stop?"

"Because I didn't lie to you! I want to help you! Can't you take loyalty when you get it?"

"I take it. For what it's worth."

"God, Marie!" He couldn't get his breath. He hung on to the pole as the transport swerved. "This is crazy!"

" I'mcrazy. Hasn't Mischa told you? Poor Marie's just not that stable."

"You're acting like it!" There were people all around them, giving them room, determinedly avoiding their vicinity even standing shoulder to shoulder with them. He couldn't get breath enough to argue. He felt crushed by the crowds. He clung to the pole with one hand, people sitting behind them, the dock business frontage passing in a blur. Green sector was coming after blue, where, according to what they'd seen coming in, Corinthianwas docked. "Where are we going? The obvious?"

"Not quite," Marie said, leaving him to wonder, because they couldn't discuss murder on a crowded transport.

He didn't want Marie arrested. Marie wasn't going to give him an answer here anyway, and he wasn't entirely sure, by that last answer and by Marie's sarcasm about poor Marie and Mischa, that Marie wasn't still on to something that didn't involve attacking Corinthianbare-handed, or doing something that could get both of them… he recalled Mischa's warning all too vividly, and had a sickly and immediate fear in the pit of his stomach… caught by station police and ground up fine in station law.

Held on station while the ship went on without them. Psych-adjusted, however far that went, until they didn't threaten anyone.

Stationers wouldn't kill you, no, they didn't believe in the death penalty. When the psychs were through with you, you couldn't even wish you had that option. That was what Marie was risking, and he shut up, because he didn't knowwhat the local law was; he didn't know whether just suspicion of intent to commit a crime could get you arrested—it could, on Cyteen Outer Station, and he didn't want to talk about specifics or name names with witnesses all around them. He just clung to the pole on the overcrowded transport, watched Marie for some evidence of an intent to bolt, and watched the numbers pass as they trundled along from blue dock, where the government and the military ships came in—a government contracted cargo didn't entitle them—toward green dock, ordinary merchanter territory, closer and closer to Corinthian.

The transport stopped just before the green section doors. Three passengers got on, maybe ten or fifteen people got off. A transport passed going the other direction, and stopped near them. He stood ready to move in case Marie should try to lose him again, and go the other way around the station rim. But she stayed still, refused when he pointed out to her that there was a seat free. Someone else took it. Marie held to the pole, not saying anything, but sharp and eager and not at all distraught—happy, he kept thinking, uneasily, happy and alive to her surroundings in a way he'd never seen in his life.

They passed the section doors and rolled into green. He didn't know Corinthian'sexact berth, but he had it pegged from the visual display as somewhere a third of the way into green out of blue.

He wasn't ready for Marie's hop off the transport as it slowed for a flag-down. He jumped, and tagged her quick pace along the frontage of bars and sleepovers, overtook her as she stopped and waited for him.

"What are you doing?" he hissed. "Marie, what are you doing? Tellme when you're getting off!"

"The berth's right down there," Marie said, gazing down-ring, deeper into green. "They're showing as offloading."

He could see the orange light, but only a single transport was sitting, loaded, at the berth. "Not moving."

"Taking their own time, for certain. I want a look at the warehouse and the company where that's going. The transport logo says Miller."

It sounded better than shooting at Corinthiancrew. "What are we looking for, specifically?"

"What we can find. What they're dealing in. " She grabbed his sleeve and drew him back against the frontage of a trinket shop as a man walked past them. He was confused for a moment, looking for obvious threat on the man, but Marie didn't let up.

"That's a Corinthianpatch. Corinthianofficer."

Sleeve-patch on the light green coveralls showed a black circle, an object he understood was some kind of ancient helmet. Crossed missiles. Spears. He'd learned that word from Marie. The patch had never looked half as much merchanter as military.

But, then, that described Corinthianto a tee.

And that might even be a cousin, striding along as if he owned the dock. Or a cousin's shipmate, he amended the thought, considering that the slurs about hire-ons and sex as a pre-req for employment that he'd heard all his life from his cousins were probably entirely true. He found himself nervous, unaccountably afraid, even in this degree of proximity to the ship and a side of his life he didn't want to meet.

"Come on," Marie said, and tugged at his arm, urging him closer to that berth.

"No!" He disengaged, grabbed her arm and drew her back. "You said you'd settle with them in the market. You said you were looking for. something in the data."

"Scared?"

"You can't go down there, I won't let you go down there."

"Won't let me?"

"I won't. If they spot a Spritepatch, they're going to be all over us. It's crazy, Marie! If you can fix him through the market, do it, I'm with you, I'll help you, but I'm not going to see you go down there and do something stupid!"

"I'm fine. What's to worry about? Afraid to say hello to your father? I'm sure he'd be interested."

The cousins who gave him trouble had nothing on Marie. "I doubt he knows I exist. Unless you know a reason for him to."

"Interesting question."

"Marie,—for God's sake—"

"It's not a problem, Tom, I don't know why you're making it a problem. We just go a little closer, have a look around…"

"You lied to me."

"I didn't lie."

"Marie, what do you care now? After twenty years, for God's sake, what could you possibly careabout that man? I don't. I don't give a damn where he is, what he does, I don't want to meet him, I don't want to know anything about him."

"Are you afraid?"

"No, I'm not afraid, but—"

"Liar yourself."

"Do you want him to rule your life, Marie? Is what happened twenty years ago going to govern your whole damned career?"

Marie's hand was in motion, and he'd gotten faster over the years. He blocked it. It stung, even so.

"Don't you lecture me!" Marie hissed. "Don't you lecture me, Thomas!"

"'Bygones be bygones.' Hell!"

He wasn't looking for the second try. He didn't intend the force of the hand that blocked it.

"Cut it out, Marie!"

"Don't you lift a hand to me, don't you ever lift a hand, you hear me? Damnyou!"

"I said cut it out!" He intercepted the third try, realized he was holding too tight and let go. "I'm not him, dammit, Marie, I'm not him, God, stop– stopit, Marie!"

She got a breath. She was absolutely paper white, staring at him with white-edged eyes, mouth open—he was shaking. She could still do that to him, he didn't know why, except that she could make him mad and that when he was mad he didn't think. He could hit her in his temper and maybe hurt her, maybe wantto hurt her, that was the fear that paralyzed him.

She got her breath. She stared at him. "Whose side are you on?"

"I didn't know there was a side!"

"You damned well believe there's a side! Don't you talk to Mischa behind my back! I didn't have to have you. I didn't have to keep you. And what's fair—what's fair, Tom, your talking to Mischa, when Mischa never did one damned thing to help me, my own ship never did a damned thing to help me—like it was all myfault—"

"I know what you feel, Marie, I don't blame you, but you don't know—"

"You don't know what I feel! You don't know any part of what I feel. Don't give me that!"

"I don't want this ship to leave you in some station psych unit!"

"I'm not stupid, boy! Does Mischa think I'm stupid?"

"Mischa doesn't have a damned thing to do with my being here, I'm here for you, Marie, for God's sake, don't act like this! Listen to me!"

"Get away from me!" She shoved him off, ran along the frontages, and he ran after her, caught her, but she started hitting him.

"Marie,—"

"Hey!" somebody said, a voice he didn't know. Someone grabbed him hard from behind and shoved him, Marie broke and ran, and he was staring at an angry spacer a head taller and a good deal wider, yelling, "What's your problem?"

"That's my mother, dammit!"

The man grabbed him by the collar. "You treat your mama like that?"

"She's in trouble! Let me go!"

"What trouble?"

"Let go!" He broke the hold and ducked, ran toward Corinthian'sberth, and stopped, having lost all sight of Marie. Someone came running behind him, and he swung around, held up both hands in token of peace, ducked the man's attempt to grab him again.

"I'm telling you that's my mother, it's crew business, I'm not after a fight—just leave me the hell alone, she's breaking regs, I got to find her!"

He shoved the man off, ran down the dock closer to Corinthian, hoping he'd find some hidey-hole Marie might have found—there were bars and he skidded into one, hoping for a service door—saw one, but it was behind the bar. He kited back along the wall as the damnfool spacer came in looking for him. He slipped out the door behind the man's back, then ran down the row to the second bar over, and into the far dim back of the room, in case the man should give it another try. He was out of breath, hoped the man hadn't called the cops. He saw a public phone and went to it—it was too far around the station rim to rely on the pocket-com. He punched in the universal number for ship-lines, Sprite'sberth at orange 19, then the internal number for bridge-corn.

"This is Tom Hawkins. Put me through to the captain, this is an extreme emergency."

Mischa came on, immediately, with, "Where did she lose you?"

"Green 10," he said, shamefaced. God, not even a What happened?

"Kid, stay put, do you copy? Where are you right now?"

He had to look up at the bar name on the back wall. "The Andromeda. "

"You don't budge from there. Do you copy? Don't budge. Saja's on the dock. He's had you in sight. He's been trying to catch up to you since you left, damn your hide."

Chasing us, he thought. Why? They had the com. Why didn't they just call us?

"Yes, sir," he said. "I'll be here. " Imagination painted what Marie might be up to, trying to get on board Corinthian, lying in ambush for their crew on dockside—getting caught at it, and arrested, because Corinthianhad probably gathered all sorts of evidence on Marie's intentions over the years, if Mischa was right about the messages she'd sent.

He hung up. He followed the edge of the room, around the tables, not to leave the bar, but because he wanted not to be visible from the door. Traffic was moderate in the establishment. A group of spacers came in and went to the bar. He spotted a darkness about the patch. It could be Corinthian. He couldn't tell from his vantage; and the man that was following him hadn't shown. He thought he might just sit down in the corner and order a drink, but it wasn't a table-service kind of place, you had to go up to the bar, and he wasn't eager to go up there with the newcomers.

He took a look outside, a careful look-see, anxious whether there was any sight of Spritepersonnel, or whether the man who'd followed him into one bar was still searching.

No sign of either. But he saw Marie, down the row, just standing in front of some shop, looking across the wide dock to Corinthian'soperations zone.

He could go back and call Mischa. He could lose her, that way. He stayed where he was, thinking Saja and his group could spot him that way, and thinking to keep Marie in sight.

But Marie started to walk along the frontage, still in the direction she'd been going, with consistent looks toward Corinthian'sarea.

Stalking them. He stood watching, looked frantically for Saja to show up, and. saw Marie getting further and further away.

Screw it, he thought. Mischa knew where he was better than he was going to know where Marie was if he didn't move. He started walking as fast as he could—he figured running would draw attention he didn't want. He just tried to look like someone on business, without making the noise that would alarm Marie or drive her to cover down some service access that on some docksides you found unlocked.

She stopped and took something from her pocket, he was scared to death it was a gun; but it was an optic of some sort, maybe a camera, he wasn't sure. She was looking toward Corinthianand he took the chance to run, as lightly and quietly as he could, in her direction.

She saw him at the last moment, spun about in alarm and then scowled at him.

"Dammit," he panted. "What are you looking at?"

"Damn yourself. The answer's Miller Transship, 23 green, no long distance from 10. They're onloading. But that's a Miller company transport. You'd know that son of a bitch was going to deal all inside."

"What do you mean?"

"I mean he's not hiring outside help. No freight handling by any outside party. He sells to Miller, he buys from Miller, Miller's his transport, his commissioned supplier…"

"That's not illegal, is it?"

"No, it's not illegal. It does mean there's minimal contact with people who might ask questions. God, I wish we'd been here just five days ago."