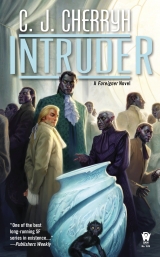

Текст книги "Intruder"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

“Anything?”

His mother briefly held up a forefinger. “Within the bounds of size and taste, son of mine.”

“A television?”

“No.”

“Honored Mother, it is educational!”

“When one has a good recommendation from your tutor, one may consider it. Not until then.”

He sighed. He was not in the least surprised. Even mani had not let him have a television.

“One day, son of mine. Not now. And because you are young, there must be a few other restrictions. You may pick antiquities, but they must be only of metal or wood, nothing breakable, nothing embroidered, and nothing with a delicate finish or patina.”

“One has never broken anything! Well, not often. Not in months.”

“One trusts you would not willingly be so unfortunate. But if your choice of furnishing is breakable, if it can be stained or easily damaged, it must notbe an antiquity or a public treasure. And do not overcrowd your rooms, mind. Listen to the supervisor’s advice. And note too that a respected master of kabiu will arrange what you choose in a harmony appropriate to the household, so do not give him too hard a task. You will make a list of the tag numbers of those things you wish moved to your suite and deliver that list back to the supervisor. Or you can take back any of your old furniture you would like.”

“One would ever so prefer to choose new things, honored Mother!”

“Then do.” She handed him the paper and the plan. “So go, go, be about it!”

“Yes, honored Mother!” He sketched a bow and headed for the door at too much speed. Great-grandmother would have checked him sharply for such a departure. He checked himself and turned and bowed properly, deliberately, lest he offend his mother and lose a privilege just granted. “One is very gratified by your permission,” he said properly. “Honored Mother.”

A very faint smile lay under her solemnity. It was his favorite of her expressions.

“Go,” she shaped with her lips, smiling, and gave a little waggle of her fingers.

He left quietly, shut the door, and let a grin break wide as he faced his aishid, fairly dancing in place.

“We get to go down to the storerooms and pick out furniture!” he said. It was the best, most exciting thing since he had gotten here. He held up the papers. “And you can pick, too!”

The papers with the Ragi seal on them meant they had permission to go to the lifts. By themselves. And Lucasi and Veijico, in uniform, had their sidearms with them, and Antaro and Jegari had the small badges which meant Guild-in-training. The guards at the lifts made no objections at all to such a proper entourage, with proper papers. And Lucasi had a lift key, which he used once they got in. “So nobody can stop the lift,” he said importantly, as the lift clanked into motion.

They went straight down for a good distance; the lift stopped and let them out in a very officelike corridor that showed other, dimly lit corridors. The place was significantly deserted. Spooky. Their steps echoed.

Lucasi had the paperwork, but did not so much as check it, not since his first look; he said something obscure to Veijico, she said, “Yes, one agrees,” and they kept walking down the hall, arriving at the supervisor’s office, having contacted the supervisor as they walked.

And the supervisor very politely rose as they entered, looked at the official paper, bowed, then took up a stack of white tags with strings and a little roll of tape, which he brought with him. Veijico gave him the permissible paper with the room sizes. And the supervisor personally led them out and down the hall to a long, long dimly lit side hall, past doors with just numbers on them. He opened the one marked 15 and turned on the lights inside.

It was a huge, dim, cold room full of furniture that made shadows, shadows upon shadows, more than the lights could deal with. The whole room smelled of something like incense, or vermin-poison. And it held the most wonderful jumble of beds and chairs, some items under brown canvas, some just stacked with pieces of cardboard or blankets between.

“One might show you first what is already tagged for you, young lord,” the supervisor said.

“One wishes to see it, nadi,” Cajeiri said, and followed the man to a set-aside area with a little bureau and a little bedstead and a rolled up carpet. The bureau and the bed had carved flowers. And he almost remembered that bureau with a little favor.

But it was undersized. Baby furniture. It was downright embarrassing to think he had ever used it.

And there were far more wonderful things all around them.

“We are permitted to choose different ones,” Cajeiri said.

“That you may, young lord. If one could ask your preferences, one might show you other choices.”

“Carving,” he said at once. He had seen better carving on a lot of furniture around them, some with gilt, some without. “A lot of carving. With animals, not flowers, and not gold. The most carving there is. You would not have any dinosauric”

The man looked puzzled. “No, nandi. One must confess ignorance of such.”

“Well, big animals, then. With trees. Except,” he added reluctantly, “we are not permitted to have antiquities.”

“I know several such sets,” the supervisor said, and led the way far down the aisle between towering stacks of old furniture.

The first set was all right, dusty, but the animals were all gracefully running, more suggestions than real animals. The second one had animals just grazing. That was fine. But not what he wanted.

The third, around the corner, had fierce wild animals snarling out of a headboard and a big one with tusks, staring face-on from a matching bureau with white and black stone eyes. “This one, nadi!” he said. “And this!”

So a tag went on that set. And he had most of the bedroom. It was a big bed. Bigger than the one he had in mani’s apartment.

“You will need chairs for a sitting room, young gentleman; we have a suggestion for seven chairs. And a table. A desk for an office. Carpet for three rooms. All these things.”

“And my aishid will have their beds and carpets,” he said. “And they can choose for themselves. Whatever they want. But we favor red for ourselves.”

“Red. One will strive to find the best,” the supervisor said.

There were five wonderful chairs. Mani would approve. They were heavy wood and tapestry had the most marvelous embroidery of mountains in medallions on the backs and seats, each one different. There was a side table of light and dark striped wood that was almost an antique. And for his office there was a desk that had a picture of a sailing ship, an old sailing ship, with sails. He liked that almost as much as the bedroom set. It reminded him of Najida.

There was a red figured carpet that was fifty years old and hedging on antiquity, too, but the supervisor said if it was in the bedroom, it would surely not be spilled on; and it was a wonderful carpet, with pictures woven in around the border of a forest and fortresses and animals, with a big tree for most of the pattern, but the bed would cover that.

Then his aishid picked out beds and side tables and chairs for their rooms: Lucasi and Veijico liked plain furniture with pale striped wood, and Antaro and Jegari liked a dark set that had trees and hunting scenes like Taiben forests, and they agreed to mix it up, because Veijico and Antaro had one room and Lucasi and Jegari had the other. But that was all right, too: Mother had said there would be a master of kabiu to sort all that out and put vases and hangings and such that would make it felicitous, however they scrambled the sets.

It was a lot of walking and pulling back canvas covers and looking at things. He thought they would all smell of vermin-poison by the time they got out of the warehouse.

But they were only half done. The supervisor showed them a side room and shelves and shelves of vases and bowls and little nested tables and statues and wall hangings. The supervisor pulled out several hangings he thought might suit, and Antaro wanted a hunting one that he rejected, himself. He took one that was mountains and lakes and a boat on the lake, and Veijico took another that was of mountains, while Lucasi and Jegari took hunting scenes and another mountain needlework.

And there was, in this place, a marvelous hanging that was all plants, and all of a sudden Cajeiri saw what he wanted for the whole room, the whole suite of rooms. “I want that one, nadi,” he said. “But I want growing plants, too. I want pots for plants, nadi.” He and his associates on the ship had used to go to hydroponics, and nand’ Bren’s cabin had had a whole hanging curtain of green and white striped plants, and just thinking about it had always made him happy. He suddenly had a vision of plants in his rooms. Hisrooms. And plants were not antiquities, and they could not possibly be outside the rules.

“One will make a note of that, young lord,” the supervisor said, and was busy writing, while Cajeiri peered under an oddly shaped lump of canvas. “One will notify the florists’ office.”

One was sure it would happen. He paid no more attention to that problem. He saw filigreed brass. And there proved to be more and more of it as he pulled on the old canvas, canvas that tore as he pulled it, it was so old.

The brass object was filigree work with doors as tall as he was, a little corroded and green in spots, and it took up as much room as two armchairs. It was figured with brass flowers that made a network of their stems instead of bars. And it had a brass door, and brass hinges, and a latch, and a floor with trays.

He worked to get all the canvas off.

“That is a cage,” the supervisor said. “From the north country. It is, one fears, young gentleman, an antique, seven hundred years old.”

“But it is brass, nadi!” He wantedit. He sowanted it. It was big, it was old, and it was weirder than anything in the whole warehouse. It was the sort of thing anybody seeing it had to admire, it was so huge and ornate. And he wanted it to stand in the corner of his sitting room, whatever it was, with light to show it up, with plants all over. “I am not to have fragileantiques,” he said. “Brass is different. My mother said I might have brass.”

The supervisor consulted his papers. “That exception is indeed made, young lord.”

“Parid’ja, nandi,” Lucasi said quietly. “In such cages, people used to keep them for hunting. They would go up in the trees and get fruit and nuts. And they would dig eggs. That is what this cage was for. To keep a parid’ja.”

“It is wonderful,” he said. “One wants it, nadi, one truly, truly wants it!”

“It is quite large,” the supervisor said. “It really does not fit easily within the size requirements.”

“I still want it, nadi,” he said, and put on his best manners. “One is willing to give up two chairs or the table, but I want it. It can even go in my bedroom if it has to.”

“In your bedroom,young gentleman.”

“It can stand in a corner, can it not? I shall give up the hanging if I must. I want this above all things, nadi!”

The supervisor took a deep breath and gave a little bow, then put a tag on the cage and noted it on the list. “One will run the numbers, young gentleman, and assign it a space, if only doors and windows allow.”

“We haveno windows, nadi!” For the first time ever, that seemed an advantage. “And not many doors!”

“Then perhaps it will fit, withyour chairs and hanging andthe table. Allow me to work with the problem. One promises to solve it. Meanwhile, search! You may find small items which may delight you.”

“One is pleased, nadi! Thank you very much!” He used his best manners. He hurried around the circular aisle, taking in everything. Brass meant he could have old things. He picked out a brass enamelware vase as tall as Lucasi. “For the sitting room,” he said.

That was the last thing he dared add. It was big, but it was big upward,and it went with the cage. He was satisfied. “May one come back again, nadi,” he asked, “if one needs other things?”

“Dependent on your parents’ wishes, yes, young lord, at any time you wish to move a piece out or in, we are always at your service. We store every item a house wishes to discard from its possession. We restore and repair items. We employ artists and craftsmen. Should any of these things ever suffer the least damage, young lord, immediately call us, and we will bring it down to the workshop and make whatever repair is necessary.”

He bowed, as one should when offered instruction from an elder. “One hears, nadi, and one will certainly remember. But we are very careful! We are almost felicitous nine, we are taught by the aiji-dowager and by our parents, and we are very careful!”

A bow in return. “One has every confidence in your caution, young lord. Rest assured, I shall have staff move these things to the staging area, give them a little dusting and polish, and you shall have them waiting for you tomorrow.”

“Thank you, nadi!” he said with a second bow, and they all walked back to the entry and took their leave in the brighter light of the hallway.

He was all but bouncing all the way to the lift, imagining how marvelous his suite was going to be and where hewould put things. Hewould put things. Hewould have a choice.

He had seen vids about animals. Horses. And elephants. And dogs and cats and monkeys. He had wanted a horse. And a monkey and a dog and a cat and a bird and a dinosaur. He had wantedcoh, so many things he had seen in the vids on the ship. But humans had not brought any of them with them. He had been verydisappointed that there were no elephanti or dinosauri on Mospheira.

He thought of things one could keep in a cage like that. He had instantly thought of several varieties of calidi, that laid eggs for the table—but calidi were scaly and had long claws and were not very smart. Parid’ji were spidery and furry, and moved fast and ateeggs. Like monkeys. He had seen vids. They were a lot like monkeys, but they belonged to the forests, and he had never thought of bringing one to the Bujavid.

Oh, his whole mind had lit up when they had said the cage was for that.

And when they were waiting for the lift, where nobody could hear, he stopped and said, “Can you find a parid’ja, nadiin-ji?”

His aishid looked worried. All of them.

“One can find almost anything in the city market, nandi,” Antaro said. “Or at least—one can ask a merchant to find what is not there. But one is not sure one should, without permission.”

“They are difficult to deal with,” Lucasi said. “Your father would not approve.”

“I want one. And you are not to say anything! Anyof you! I can prove I can take care of it. I have never asked you to do anything secret but this. Find me one, and leave it to methat I shall get my father’s permission for it. I am his son. He will approve things for me that he would not if you asked him.”

There was a second or two of deep quiet. And very worried looks.

“One will try,” Antaro said. “One has an idea where one might find a tame one. It may take me a while.”

“Then you shall do it,” he said as the lift arrived. And ignored the frown Veijico turned on Antaro.

He could hardly contain his satisfaction. He had the cage. He was going to have a monkey. Well, close to a monkey. He had something that was going to be fun.And he would have something alive that was going to be hisand not boring, because it thoughtof things for itself and it was not under anybody’s orders.

He had been sad ever since he had had to leave Najida, and sadder since he knew he was going to have to live in a room with no windows and just white paint.

His room would not be all white. His room would be interesting.He could not go back into space. But he had his beautiful furniture, he had his own aishid, and he had that beautiful ancient brass cage and he would have a room full of plants like nand’ Bren’s cabin on the ship. And he would have something to do unexpected things.

He had dreaded the move. Now he could hardly wait.

3

The rain never let up. The view of Tanaja and its busy port was gray and watery as the bus reached the improved gravel road, where there was at last no worry about bogging down. It was largely thanks to the skill of the driver that they had gotten out of their one difficulty in the highlands, and nobody had had get out in the downpour and push. It was, Bren thought, a very excellent bus, if extravagant. Power to all wheels was a very good idea.

It was gravel roadway now, and generally solid all the way down the hill to the first city pavement.

Tanaja was laid out as a bowl set in a hillside, and bottommost was the harbor. On a hillock overlooking the harbor—a height that the histories said had once commanded the waterside with cannon—sat the Residence, partly composed of the old fortress which had stood here but mostly, Bren understood, of the scattered stones of that fortress. Gunpowder had exploded, that being the business of gunpowder, when a Dojisigi ship with a monstrous unwieldy cannon had scored a chance hit on the Taisigi powder magazine.

The fortress had fallen, and Dojisigi clan had taken over the Taisigi lands until the Dojisigi lord had injudiciously eaten a dish of berries a Taisigi serving girl had provided.

A cannon shot from a heaving deck and a dish of berries: both had caused the city to change hands.

A Taisigi lord of that day had then built the Residence out of the rubble and thrown a great chain across the harbor, from the breakwater to the treacherous midharbor rock, that bane of careless captains, and then to the promontory that ended the harbor deep. That had saved them from the second Dojisigi attempt.

The Residence had stood safe on the hill from that time. Taisigi clan had prospered, in Dojisigi’s decline. They had had Sungeni and Dausigi and Senji for allies and were bidding fair to take Dojisigi clan as well.

Then humans landed from the heavens, and the north had accepted human technology, which left the Marid in the dust.

Worse, a war had started that had ultimately caused the evacuation of atevi from the island of Mospheira and the ceding of the whole island to humans.

And the settlement of those displaced island clans on the west coast had changed everything. The aishidi’tat, with its capital up at Shejidan, had fought the war and now controlled the west coast. The Marid had no strength to oppose the united strength of the North. And the Dojisigi and Senji snuggled closer to the aishidi’tat, playing politics for all they were worth.

The attempt to unify the Marid fell apart. The Taisigi, pent up in the bottle of a smaller sea that was the Marid, joined the aishidi’tat, in name at least.

Every generation replayed that struggle, in one form or another—Dojisigi and Taisigi, with Senji clan rising to partner, generally, Dojisigi, and the impoverished southern clans of the mainland faithfully allying with Taisigi, knowing that Dojisigi and Senji would swallow them up in an instant, if it were remotely convenient to do so.

That was the last two hundred years of history in a nutshell.

It was an ambitious undertaking, to try to shoulder history out of a deep, deep rut.

Bren folded up the notes which proposed to do exactly that and tucked them into his briefcase as the view in the front windshield became buildings and city streets.

The streets were sparse with rain-soaked foot traffic, a few trucks were out and about. One truck stopped in midturn at an intersection, doubtless to get a look at the huge red and black foreign vehicle rumbling through the ancient streets of the harbor district, causing a little delay and causing Jago and Banichi both to come forward in the bus, with Tano and Algini behind. But the truck went on, and the bus no more than slowed.

Bren drew an easier breath, and his bodyguard went back to give orders.

The Assassins’ Guild had come into Taisigi district in force a handful of days ago, with none of its usual finessecprotecting Machigi, who hadn’t been in town to be protected, but never mind that. The Guild had taken over Taisigi territory. It removed several high-ranking officials in the first hours.

It had landed far, far harder up in Senji and Dojisigi territory, taking out the lords and several others and now controlling the capitals of those districts while operatives went down into Dausigi and Sungeni clans with far more finesse.

The Guild here in the Taisigi capital were nominally under young Lord Machigi’s authority now—they had declared themselves in support of him, at least. But they had very little to restrain them should another objective occur to them.

Lord Machigi could not be easy with the situation. Neither could the citizenry of the capital and the countryside. The whole damned situation was a house of cards of the dowager’s construction.

And what was supposed to stabilize it rested in that briefcase Bren folded up and set beside him.

He breathed shallowly—hadn’t realized he had been doing it until the bus began the slight climb to the Residence hill. He watched as the bus pulled into the circular drive where it had sat the last time. Rain positively sheeted down, hammering the potted plants along the driveway, veiling the front doors. Nature was not cooperating.

Banichi and Jago came forward, and Banichi settled into the opposing aisle seat—a golden-eyed darkness against the pale grays of the rain.

“We are in contact, Bren-ji,” Banichi said. “We have spoken reasonably with Lord Machigi’s aishid, as well as the Guild. They indicate you will be asked to stay the night here. Shall we offload baggage?”

At least they had the surface elements of courtesy. “Yes,” he said. He didn’t ask whether the ten juniors with them had their orders: that was Guild business, and Guild would arrange whatever they would do out here while he and his bodyguard were inside. But they were going to go into that doorway, at the mercy of whatever situation was inside, and they were going to settle business and drive back tomorrow, given good luck.

So, yes, he said, about the baggage, and he did. Banichi stood up, Tano and Algini came forward from the back. Bren put on his brocade coat, court garb, taking care to arrange the lace at the cuffs. Jago had taken a rain cloak from the overhead and helped him put it on, protecting his clothes. His bodyguard was due to get soaked—but cloaks on Guild made other Guild nervous, so Guild habitually endured such situations, that was all. The uniforms shed water—up to a point.

Bren took his briefcase under the cloak and got a firm grip on the cloak edges as his bodyguard talked to someone not present. It was, of course, blowing a gale out there, just for their arrival.

Black-uniformed Guild came out to meet them, themselves getting wet, and with no great desire to linger long, it was sure. The bus doors opened. Banichi and Jago descended first, rifles in hand, and Bren followed, with Tano and Algini at his back. Guild-signs flew one side to the other, indecipherable, generally, as they headed directly for the doors. His aishid was fully armed. Not so the Guild who met them, as he noted. But he was the traveler, so that was allowed.

Like the rain cloak, with its hood. The lord was not supposed to be armed. And he wasn’t—this time.

He kept himself as dry as possible on the way into the building, as contained as possible within the living wall of his bodyguard. Servants were waiting, one to take the dripping cloak, others hastening to mop the water off the marble entry. A lightning flash illumined the foyer from the open door as servants hastened to shut those heavy doors.

Then they stood safe from the wind and the tail end of the thunderclap—just a little clatter of rifles being shifted and the busy noise of mops.

“Welcome, nandi,” the receiving Guild-senior said, dripping water. “Lord Machigi is expecting you.”

It was a few steps up from the entry, through other doors and onto the dry, polished main floor. His bodyguard still shed rain as he walked among them, dry now, and clad in court finery, brocade and lace.

And he was very glad to see the historic hall had not suffered in the recent upheaval. The two great pillars of porcelain sea-creatures towered serene as if nothing had ever happened here.

More uniformed Guild opened the doors between the pillars and let them into the gilt-furnished audience hall. Guildsmen across the room immediately opened the polished burlwood doors on the far side, those to the map room.

That was a good omen. Machigi had chosen the more intimate setting for the meeting.

Bren walked on through. Tano and Algini stayed outside, within the audience hall. Banichi and Jago went with him.

The far walls of the map room were massive gilt-arched windows with a view of the storm, the dark clouds, the rain-battered harbor below the heights. The opposing walls supported huge framed maps, and shelves and pigeonholes were full of map cylinders, many of evident antiquity.

Machigi rose from a chair before the massive windows. Near those windows, Machigi’s personal bodyguard stood in attendance on him, men they knew. Thatwas a great relief to see.

Bren bowed on arriving in that area. Machigi bowed slightly. He was a handsome young man. The scar of an old injury crossed his chin and ran under it. He wore a subdued elegance—dark green brocade and a sufficiency, but not an excess, of lace. By such things, one measured a man and his circumstances. Machigi was a lord. A ruler in an occupied house.

And he did not look delighted.

“So,” Machigi said, doubtless taking Bren’s measure, too, the attitude he struck, the degree of humility—or lack of it—in the bow. “Whose are you thistime, paidhi?”

“In this venture,” Bren said quietly, “I now represent the aiji-dowager.”

Not the aiji. The aiji-dowager. That was perhaps the answer Machigi had hoped to hear. The nod of his head revised suspicion into acceptance, and he waved a hand at the opposite chair, offering Bren a seat, and sat down himself. Bren set his briefcase on the floor and took the chair, a practiced effort that placed him somewhat gracefully in furniture crafted to atevi stature.

“Tea,” Machigi said to the servants, and beyond that, there could only be polite talk, a ritual settling of minds, before serious conversation.

“Your old rooms are prepared, nand’ paidhi,” Machigi said. “One trusts you came with luggage.”

“One did not presume to bring it in from the bus without direction, nandi, but it is ready.”

“Have it brought to the rooms,” Machigi said, and Bren said, quietly, “Nadiin-ji.”

Banichi, in the edge of his vision, nodded, and it was a certainty it would be done.

“You will share dinner tonight, of course,” Machigi added. “One rejoices to see you fully recovered, nandi.”

“Indeed,” Bren said. “And the same, nandi, one rejoices to see you safely recovered, as well.”

“As fully recovered as we may be, with a foreign occupation in our streets.” That verged uncomfortably on business, before tea was done. “And how does Najida fare?”

“In less happy state than this house,” he said, “but repairs are in progress.”

“And Kajiminda?”

“Has its porch now restored and is busy inventorying its collections.” A sip of tea, a slight shift of topics. “One is certain Lord Geigi’s nephew sold certain things.”

A shift Lord Machigi declined, with: “And Lord Geigi himself? How does he fare?”

That was no easy interface: Geigi and the Taisigin Marid were old allies turned enemies, now turned allies again.

“Well. Quite well, nandi.”

“And does he approve your venture here?”

“He needs not, but in fact he views it quite favorably, nandi. He has, one assures you, no wish to continue hostilities which were largely fomented by others.”

The fact that Machigi had actually been in charge of the agents who had fatally poisoned Geigi’s sister—it was questionable, since those agents had betrayed Machigi, as to which authority had ordered it. It was one of those sorts of questions which, for the peace, had to be set aside, no matter Lord Geigi’s personal feelings. Or Machigi’s innocence, or lack of it.

Thank God tea was about to be served.

The servants had brought a tray, offering a beautiful tea service of the historic, irreplaceable blue porcelain. Courtesy dictated silence while tea was poured and served, and Bren received the atevi-sized cup in both hands, finding the warmth comforting after the rainchill and a conversation that had veered toward a dangerous, dangerous edge.

“One is extremely honored,” he said. “One is honored even to seethis beautiful service.”

Machigi saluted him with his cup and took a sip, as Bren did, from a porcelain that could no longer be made. “One was glad to find it intact,” Machigi said, in the former vein, and then, in wry irony, as lightning from the windows cast everything in white, “Lovely weather for a visit, is it not? Do we take it for an omen?”

“Spring in the west,” Bren said with calculated lightness. “But one enjoys the storms.”

“And did you seriously propose to take the bus back to Najida tonight in such weather? One would hope not.”

“Worse,” Bren said, “my destination is the airport, and one would be glad to have better weather.”

“You will go to Shejidan? Or Malguri?”

“Indeed, Shejidan. For the legislative session. One hopes the weather will have blown past by tomorrow and that we will not be delayed by weather.”

“You mean to leave from Separti?”

“No, no, once we are on the road, we will call for the plane, and it should be there long before we are. We shall be in Shejidan faster by small plane than going from Separti. It is enough.”

Sip of tea. “Then one wonders the more at your determination to visit today, in a deluge.”

“The legislative session, nandi. Not to mention our own business. And the necessity to move residence. I shall have my old apartment back this session. They inform me it is ready.”

“Just so.” A little grim amusement. “You are avenged, nand’ paidhi. The Farai lord is dead.”

“One regrets—” It was disingenuous to say that one regretted the Farai lord, who had usurped his apartment, among other offences, was gone. “One regrets the loss to his relatives, at least. But not that he is removed from my premises. Had he not been there, nandi, I would never have come to the coast and we would not be sitting here. So things worked to our mutual advantage.”