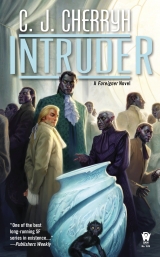

Текст книги "Intruder"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

“And I tell you that animals should not be in a city apartment.”

“He is perfectly clean. He is well mannered. And I am very sorry he bit anyone, but he was scared.”

“I will not have that filthy animal in this apartment!”

“And I will!” he shouted back, but that was not wise. He was so mad, he thought: I am my father’s heir, and you are not.And that was the truth. It was truth enough to stiffen his back.

But if he said that, things could go very badly very fast. He said instead, quietly, negotiating: “One respects one’s mother, but it is also needful to respect one’s father, and I have gotten both permission and instruction from him regarding Boji. If a servant had not violated orders, he would never gotten loose. Now he is back in his cage and doing no harm. Please accept my apologies, honored Mother, for what was done, but it was done. It will not be done again.”

There was silence from outside, a very long moment of silence.

Then: “We shall have a word with your father. You were wrong to have sent to him.”

“I believe I was not, honored Mother.”

“You are being unreasonable.”

“I believe I am not unreasonable, honored Mother.”

“Your grandfather is arriving this evening. I had intended to show him the nursery. I am quite, quite upset about this, son of mine.”

“One is very, very sorry about the nursery, honored Mother. And one promises it will not happen again.”

“We shall be sureit will not happen again,” his mother said, and then she went away. He heard the footsteps retreating, and his bodyguard was still out there, or might be.

“Jegari?” he asked. “Antaro?”

“I am here,” Jegari said. “Antaro is here. Lucasi and Veijico are down the hall in the security corridor.”

“Is it safe for me to open the door right now?”

“Yes,” Jegari said, and with several efforts he hauled the table out of the way, unlatched the door and let Jegari and Antaro in.

They both looked worried, as well they might.

Jegari said: “That was not a good situation, nandi.”

“Not ‘nandi!’” he said, vexed. He so envied nand’ Bren right now, the way he managed his bodyguard, the good feeling there always was in that household. It had been very much lacking in his father’s house. He was sure of that now. He had thought it was that they had all been crammed up together in Great-grandmother’s apartment. But now he knew that that feeling had been there for as long as he had been home. “Especially now, nadiin-ji! I shall be called Jeri today, if you please. I wish to be called Jeri.”

“Jeri-ji,” Jegari amended himself, and after a deep breath: “Lucasi and Veijico did report to your father’s security staff, and one of them has left; the other is maintaining silence, and his only instruction is to wait. Your mother’s guard is with her. Your mother’s bodyguard has ordered us to stand down or be arrested and reported to Guild; Lucasi and Veijico have refused on grounds of security, and they recommend to us to take orders only from you until there is some other order. We are trainees. We two are safe from Guild action. But they are not.”

“And,” Antaro said, “they recommend that should there be violence offered by your mother’s bodyguard, we resist and make an extreme issue of it. They are not armed. But they will resist. Extremely.”

“One is very grateful,” he muttered. “It is brave. One is very glad you are not hurt.”

“Your mother’s guard is more than upset with us,” Antaro said. “Your honored mother is not at all in a good mood, and they feel it personally.”

“Nadiin-ji, this is serious, and one is worried. Where is my father? Do you know? Why will he not come here?”

“He is downstairs. He is in a meeting.”

“Are you sureof it?”

Antaro said, “Your father’s guard is talking to him. The senior aishid is with him.”

He let go a breath then. He wanted that to be so.

“And mani and nand’ Bren are all right?” he asked.

“They are all right. Lord Machigi is arriving this evening to sign the agreement with your great-grandmother, and the whole Bujavid is under special rules right now. Your father and his aishid are in a meeting with Lord Tatiseigi, going over the agreement your great-grandmother is offering to Lord Machigi.”

“He is going to be so mad at me.”

“You toldthe servant to shut the door, nandi,” Jegari said.

“I did,” he said. “I did tell her. Why was she here? Why was she here in the first place?”

“We have no idea, nandi. Jeri-ji.”

“Do you know when my grandfather is coming?”

“Kitchen is preparing a big dinner,” Antaro said. “Your mother ordered it.”

“One suspects,” Jegari said, “your esteemed grandfather may have decided to come visit because of Lord Machigi. But he is not invited to the signing. Veijico found that out. Only invited people can get in. So he is definitely supposed to be here all evening.”

“So my grandfather is a—” He was not sure he had a word for his grandfather. Coming here to throw salt in the pot,was what Great-grandmother would say he was doing, meaning trying to take over without consulting the other cooks in the kitchen. Or in this case, coming to visit to get right in the middle of things without an invitation.

“My grandfather is not here to help,” he said. “He always shows up when things are going on. But he is not an ally of my great-grandmother.”

“The young lord of Dur is coming in,” Antaro said. “If he is not already here. So is the new lord of the Maschi. All sorts of people who areallies of your great-grandmother are coming.”

“Lord Tatiseigi is a close ally of my great-grandmother. But he does not approve of the Marid. And heis downstairs with my father.”

“One has no idea,” Antaro said. “He is head of the conservatives.”

“Except my grandfather. My grandfather is a conservative. But one does not have him and Uncle in the same room. Do you think Grandfather coming here might be because of that meeting my father is having with Uncle?”

There was a moment’s silence. “It could be,” Antaro said. “It actually could be. Your great-uncle has an invitation. Your grandfather, nandi, does not.”

“Grandfather will not be happy at that,” he said. “And my mother—” Mother was all upset with the baby coming. Everything was the baby. And Grandfather was supposedly all excited about the new baby, and calling Mother a lot. And ordinarily Mother had no patience with Grandfather. But now she was defending him and anxious to show him the new nursery and invite him to dinnerc

And Uncle Tatiseigi was in residence again and making up to Great-grandmother, and making peace with Lord Geigi, and both of them sitting drinking brandy with Great-grandmother and nand’ Bren, and all interested in Lord Machigi coming in, and this new agreement that was supposed to stop wars with the Maridc

So Grandfather was coming for supper, and Grandfather had no invitation to the big event this evening.

He wished he could ask Great-grandmother what his grandfather was up to. Or why Mother was being nicer to him than to Uncle. It had a very upsetting feeling.

And maybe it was not all about Boji.

And now Mother was mad—and upset. The pretty yellow and white nursery was destroyed—though all he had been able to see was one curtain a little askew and an unfortunate accident on the wall, and he did not think Mother really had to repaint the whole nursery or throw out all the lace curtains and all.

But Mother was upset: that was what he had heard in her voice. She was very, very unhappy, and he was not that sure now that it was all about Boji at all.

And his mother was sounding more and more like Grandfather. That upset him. Mother was not behaving well at all lately. Not since the baby. Not since—well, Mother had not been wholly nice to him since he had gotten back from space.

And there was nobody more grownup to make grownups behave.

But—there were people. There were people who were downright scary and other grownups were scared of them for very good reasons.

He had an idea. He had a very good idea. It was scary. But in his opinion, certain people, particularly his grandfather, deserved it.

He went back into the hall, to his desk, sat down, and laid out a sheet of formal note paper, shaking the lace of his cuff out of the way as he took pen, dipped it in ink, and wrote.

Esteemed Great-uncle Tatiseigi, Lord of the Atageini and Tirnamardi, I believe that my grandfather, the Lord of the Ajuri, is on his way to Shejidan.

I do not think he meant to come this soon. I think he knows Lord Machigi is on his way here, and I think he is very much against Great-grandmother in everything. Mother has just complained of Great-grandmother very unfairly. She says Great-grandmother has been a bad influence on me. Grandfather is certainly going to take her side. Please come visit and rescue me.

He thought honesty was probably a good thing, because his mother was going to blame him for everything.

Honored Great-uncle, my mother is particularly angry because of a parid’ja in an antique cage, who escaped and damaged the nursery. My father said I might have him. My mother calls him a filthy beast and she says keeping animals is Great-grandmother’s idea, when I know you also have very fine mechieti, like Great-grandmother, so one knows you understand my situation. Please, esteemed Great-uncle, I do not want to ask Great-grandmother to come rescue me, because if my mother said such things to her, one does not know what might happen. But, Great-uncle, you are very brave and very powerful. You have connections with my mother, and she respects you. I would be very grateful if you would come to the apartment and ask me to stay with you for a few days. You are very respectable with everyone and everybody will listen to you. Please help me and take my side, and I shall never forget it. One knows you are very busy tonight, but all you need to do is come here and send me to your apartment, and I shall bring the parid’ja and stay there and be no trouble.

He read it once, for good measure.

Uncle Tatiseigi had alwayswanted custody of him, well, except the time he had ruined the driveway. But Uncle Tatiseigi had always been extremely jealous of influences on him, even mani. And Uncle Tatiseigi was not at all on good terms with Grandfather. He was afraid, but he was not going to admit that. SurelyGreat-uncle would come.

He folded the letter, he sealed it very properly—he used a little ring he had, which was not a proper seal, but he had a small waxjack at his desk, and it served.

“Take this,” he said, “one of you. Get to the servants’ passage, get downstairs, and get down to my great-uncle.”

“If he is in the meeting, still,” Jegari said.

“You can give it to his bodyguard.” Everybody would be standing around the door of the meeting-room, including his father’s bodyguard, and they had tried that, and Father was still not here. But Uncle might get a message.

Uncle could at least move his father. Bothof them might come up here. That would be the best thing—if only they agreed with him.

It was a terrible situation to be in.

And he had not asked for it. More than Boji, he had done no wrong. He really had not done anything wrong. That was the puzzling thing. Always before, if he was in trouble, he had done something really, really wrong.

But right now, things just seemed to be happening that were not all his fault.

17

It was absolutely necessary for the paidhi-aiji, and Lord Geigi, to show up at the event in full court dress. That was first and foremost. They had to appear, they had to give the right impression, and they had to be protected against the very real possibility that some attendee might not be on the up and up.

That meant bulletproof vests all around and a last-moment fitting. Narani was determined to have a good fit on persons he sent out the paidhi’s door—stylish, entirely unremarkable as what they were, and compatible with court style—and the poor tailor had shown up at the door with his case just about on the hour, every hour since supper. Bren had suffered three fittings, Geigi two—since Geigi’s security had gotten together with Bren’s and agreed that, indeed, bulletproof and pale silk was the latest fashion.

But lords were dressing for dinner, flowers and good wishes were reportedly piling up in the Bujavid security office, and so many people being involved, ment the news of Machigi’s arrival was now getting out.

And if the gossip of tailors and flower arrangers and number-counters hadn’t let the secret out to the building staff by now—its intermediate step on the way to full press coverage—if all of that failed, there was a conservative caucus, and they could always be counted on to blow any secrecy wide open.

Neither the liberal nor the conservative caucus was a meeting politic for the paidhi-aiji to attend. Nor were they apt for the aiji-dowager’s attendance—by a long shot—though she occasionally did meet with the aristocratic side of the conservative caucus, where it regarded her passion for the environment.

Tatiseigi, however, was reportedly down there—he was in his element. In very fact, Tatiseigi had convoked the meeting and asked Tabini to be there, an attendance nearly unprecedented. One understood the Merchants’ Guild had also been invited to appear, and almost certainly the porcelain trade would come under discussion, if only as a gloss.

The Assassins’ Guild was naturally there—not officially on the speakers’ list—they didn’t come to committee meetings and the like. But they were standing by every aristocratic member in that meeting.

Which was how information was flowing to his staff. So either the Guild leadership approved of that leak going to certain staffs—or his staff was getting it second-hand from the dowager’s or Tabini’s.

There had been the usual conservative viewings-with-alarm for openers. There was plenty of viewing-human-influence-with-suspicion. That was traditional, like the counting of numbers for felicity.

That had, predictibly, occupied the entire front of the meeting. It had not made the paidhi’s cold supper happier. But the execration of human influence was the establishment of bona fides for certain speakers, so it was understandable; the usual speakers were the Old Money of the aishidi’tat, in the main. Ragi clan ruled the aishidi’tat, some said, only because the Old Money could not abide one of their own lording it over the rest.

And then, wonder of wonders—Lord Tatiseigi had taken charge of the meeting and opened his statement with the accurate observation that there was no region of the aishidi’tat moreconservative than the Marid.

He had further stated that if the conservative caucus wished to find kindred opinions in political debates and in the legislature in the future, they should work to stabilize that region of the continent, put power in hands with but one neck, as Jago so colorfully quoted Tatiseigi—and insist that everybody listen to the Assassins’ Guild’s new establishment there and operate through them in the old traditional way.

That last suggestion, Jago reported, had occasioned another furor. Whyhad the Assassins’ Guild, that bastion of conservative opinion, recently run amok, one asked, if not the ascendancy of liberal elements within it?

Because, Tatiseigi had retorted shrewdly, his lifelong neighbors, the Padi Valley Kadagidi, who had disowned Murini as a failure and supported Tabini’s return to the aijinate, had been lying: It was all designed to put the clan back into a position of great influence.

The Kadagidi, Tatiseigi had gone on to say, had publicized an enemies’ list that only beganwith the liberals of the legislature. But, Tatiseigi proposed, the real rivals of the Kadagidi were not at all the liberals. They were the other Old Money clans, whose leaders were in jeopardy from Kadagidi aspirations. The Kadagidi sat at the very heart of the aishidi’tat, assisting and backing the renegades of the Guild in districts south of Shejidan. The Kadagidi could not be in favor of the Guild action which had removed the Shadow Guild from the Marid.

And they had not deigned to show up yet in the legislature.

“Clever man,” Bren said, hearing that. “How was it received?”

“With the usual objections from Lord Diogi,” Jago said wryly. Diogi was not one of the brightest lights in the legislature. Nor that influential. Tatiseigi, notoriously noton the cutting edge of technological developments, was equally famously no fool and weighed far more in debate than Diogi.

“But no other objections,” he said.

“There is debate on mechanisms,” Jago reported, “to assure that there will be no competition to the detriment of certain regional interests. That these matters be referred to the Merchants and reports received.”

“Understood,” he said, and sat thinking about Lord Tatiseigi, who had made some very unprecedented movement on various questionscmostly on issues definitely to Tatiseigi’s advantage, taken all together. It seemed on the one hand too good to be true—and on the other, the constellation of advantages, ones he personally had labored to collect, precisely to try to head off conservative opposition—were real advantages.

Well, he’d made more of an impact on Lord Tatiseigi than he’d thought. Tatiseigi had quite happily taken the opportunity to fling stones at his neighbor the Kadagidi, via the whole program—and had gotten in a good hit or two. He wasn’t unhappy to hear that, and the Kadagidi were going to regret not being in the meeting. Possibly the Guild as currently constituted had been at work there, too—

–or possibly the Guild members that served the Kadagidi were having problems that Jago did not have clearance to report.

Might some that protected that house have gotten themselves personally involved in the fracas down in the Marid? That would be interesting.

Might there have been a thinning of the ranks, leaving the Kadagidi with less than their usual protection?

Some among the Shadow Guild had fled from Guild vengeance to the south. Naturally those that they knew had run first were the leaders.

And would the Kadagidi be stupid enough—or scared enough—to admit them back into Kadagidi territory? Surely not.

“Is there, Jago-ji, anyof the Shadow Guild in the Kadagidi district? Is Lord Tatiseigi advisedly taking that position?”

Jago’s gold eyes flicked upward. And down, hiding secrets. “Perhaps. We have personally taken aside all of Lord Tatiseigi’s bodyguard and explained certain things forcefully. He is under heavy protection.”

“One understands,” he said.

Jago went back about her business elsewhere.

And he went to consult with Geigi, who was in the hands of his aishid, being dressed.

“Tatiseigi is speaking in favor of our position,” he said. “We are doing very well, thus far. He has not carried the day, but it seems reasonably likely that he may do so.”

“The porcelain,” Geigi said, fastening the vest, “has incredibly sweetened his mood. Had I known this a decade ago, I swear I would have sent the old reprobate my best!”

“I believe it is the contemplation of gain, Geigi-ji. Gain from transport of grain: he is admirably well-situated for it. Grain headed south and fish to the north. Not to mention the porcelains.”

“Well, well, well,” Geigi said, and turned to accept his coat. “I swear to you, I shall ply him with little gifts. I shall remember it if the weather truly holds fair, from the Padi Valley.”

“He is a very shrewd politician,” Bren said. “If we can enlist him, so much the better for the dowager’s cause.”

There were a dozen things still to do—one of which was to look up and absolutely fix in his head the names of two similarly named bays on the East Coast that he had confused before, and the names of several contacts in that district.

He was doing that when the office door opened, and Banichi came in.

“There is a difficulty, Bren-ji,” Banichi said.

“Difficulty.” Adrenaline came up. Instantly. “What difficulty.”

“The young gentleman,” Banichi said. “He sent to his father earlier to request his father come back to the apartment. Now he has dispatched one of his aishid from the apartment with a message to Lord Tatiseigi.”

“To Tatiseigi.” He was immediately confounded and chagrined—puzzled that the boy, if he was distressed at not having his own invitation to the evening event, had not sent to the aiji-dowager and chagrined that the boy had not sent to him, who was right next door. He would have explained to the young gentleman—the high security involved, the chance of difficulty—and the statement it would make having the aiji’s son present. The omission of an invitation was a political decision, not an accident. “Should I go there, Nichi-ji?”

“The young man has reportedly had a falling-out with his mother,” Banichi said. “That is the matter at issue. And one does not believe it would be a good idea, Bren-ji, either to send us or to go yourself.” Banichi looked worried. So, he was sure, did he. They had both heard Tabini’s account of difficulties.

And an issue had to arise today. This evening. “Perhaps,” he said, “we should notify Jaidiri.” That was the chief of Tabini’s bodyguard.

“Jaidiri knows, now, from Tatiseigi’s bodyguard,” Banichi said.

“Damn. One hardly knows what to do.”

“There is nothing that suggests itself,” Banichi said. “Damiri-daja’s father is in the city.”

“Twice damn,” Bren said, and there went his concentration on details. Damn and damn. “Keep an eye on that situation. Keep me posted.”

“Yes,” Banichi said.

He went to have a concentrated look at his maps, to fix the names in his head. He tried not to think what might be going on next door, and he told himself an eight-year-old within a very little of fortunate nine had been desperate, appealing to his great-uncle and not his great-grandmotherc Hewas in possession of information internal to the family and dared not send down to Ilisidi’s apartment. She would march in, already at a pitch of nerves from the Machigi affair, and if there was war to be had on Cajeiri’s account, she would declare it.

And the fight that would create in the chief household—one didn’t want to contemplate. The boy was far from stupid. He had not sent to her.

Please God he had not sent to Ilisidi.

Banichi came back to his office, this time with Jago, in some urgency. “Tabini-aiji himself has left the meeting, stating for the membership that he has received an urgent message. Lord Tatiseigi’s guard, on the advisement of Tabini-aiji’s bodyguard, has held back the message from the young gentleman and has not yet shown it to Lord Tatiseigi.”

Bren drew a deep breath. “We should probably notify Cenedi, if he has not been told, but one must emphasize he should keep the news from the dowager. Is the caucus continuing?”

“There was some concern,” Jago said, “in the sudden departure of Tabini-aiji. There was speculation of some incident involving Lord Machigi. Lord Tatiseigi has told them it is a Bujavid security concern and does not involve Lord Machigi.”

“Excellent.” That sort of issue would be rated severe, but the sort of thing that, once attended at high levels, would cease to be a threat. And it was the sort of disturbance that routinely happened around important events. “Brilliant. Lord Tatiseigi deserves credit for that one.”

“Lord Tatiseigi’s bodyguard will certainly meet his displeasure,” Banichi said, “once they admit the content of that message.”

One of Cajeiri’s pranks gone awry, maybe. Maybe an attempt to leave the apartment and go to the signing.

Or maybe not.

With all else that was going on in the worldcit was not safe.

Not with the rejection of a bouquet in the Taisigi mission foyer, and not with the arrival of the Taisigi lord, and not with Damiri-daja’s grandfather inbound and her great-uncle, in that meeting downstairs, just having shifted the conservative balance over to a side not profitable for that gentleman.

There were just too damned many pieces in motion for a good-hearted boy to have any room for mistakes.

“One is quite concerned about the timing, Nichi-ji.”

“We are concerned,” Banichi said, “but the aiji will be in the apartment in a matter of moments.”

Tabini would handle it. Being in the blast zone would not be a good thing.

“Dur is on his way to the Bujavid now,” Banichi said.

“One is grateful for Dur,” Bren said. “Do we have any information on the Ajuri’s whereabouts? Or Machigi’s?”

“Machigi is having supper,” Jago said. “The Ajuri lord is only now leaving the airport.”

“We are expressing concern to the Guild,” Banichi said, “about Ajuri’s intended visit and, taking a little on ourselves, we would advise the Guild on the situation in the aiji’s apartment. We believe any directive to delay Ajuri’s arrival in the Bujavid will have to come from Cenedi. With your authorization, Bren-ji, on such a matter.”

“Send to Cenedi,” Bren said.

Damn, court intrigue and Guild maneuvering. Ajuri’s own bodyguard, if the Guild directed, might be able to put the brakes on the old man and keep him quiet. But it was not guaranteed they woulddo it, if push came to shove and the Ajuri lord put pressure on them.

It was not even absolutely guaranteed where their sympathies were within recent Guild politics.

Damn again. It was not the time for a domestic quarrel in the aiji’s house to play out. And it did not need witnesses.

The last thing the aiji’s household needed was outside interference.

18

Things had been very quiet for quite a while. Boji had ceased hopping from place to place and clicking at every point of vantage in the cage.

But they were no calmer, Cajeiri thought. His mother had the servants all in a stir, probably to do with the nursery, coming this way and that down the hall, and they had had no word from Lucasi.

Then they heard the front door open.

It might be Lucasi with an answer from downstairs. It might be Uncle Tatiseigi, coming to take up for him, and maybe Uncle could just sit in the sitting room and drink tea with Mother and reason with her.

If Grandfather did not show up for dinner.

But it was a lot of people that had come in.

Uncle’s bodyguard, he supposed, listening with his ear against the door.

Then steps came toward their door, just one person, which was, he was sure, Lucasi. And sure enough, the knock came, the signal, so he got out of the way, and Veijico opened the door, with Antaro and Jegari standing close in case it was a trick. Lucasi squeezed into the room and set his back to the wall as Veijico shut the door and locked it.

“Is my uncle here?” Cajeiri asked Lucasi, who could have used his communications to tell his partner what was going on, but hadn’t. Possibly, Cajeiri thought, that had been because he was trying to keep the whole business as quiet as possible.

But Lucasi had dropped his official face and showed a very upset expression. “Nandi, it is your father.”

“My father.” That was good and bad. “By himself?”

Lucasi gave a little bow. “One regrets. I gave the message to your great-uncle’s bodyguard, and the senior of that guard talked to your father the aiji’s senior; they reported it to your honored father, and your father immediately left the meeting. Lord Tatiseigi has stayed there, and your father’s bodyguard was not in contact with the guard up here on their way. He asked me, and I told him everything that has happened, while we were coming upstairs. Your father is angry, nandi. He is very angry. He told me to come here, keep the door locked, and to stay out of the way. And not to let you leave, either, nandi.”

“Are we in trouble?” he asked with a sinking heart.

“One has no idea what is going on, nandi.”

Father, and not Uncle Tatiseigi. Uncle and Mother would have just shouted at each other, and everybody would have blown off the heat of their tempers, and that would have been all right—tempers were always better once everyone had yelled at each other.

But with Father here, and telling him keep the door locked, seriousthings could be going on.

“Would you care for tea, Jeri-ji?” Antaro asked him. But he said no.

“All of you may have some,” he said, and walked back over to Boji’s cage, worried, just worried.

Scared.

He really did not know what might happen if his father came in mad from being pulled out of the meeting and ran into his mother when she was mad about Boji. Father could agree with Mother and order him to send Boji back to the market, that was one thing that could happen. But far, far scarier things could happen.

He even thought—he had had nightmares before in this place—about people shooting up the apartment, and how the old staff had been killed in this apartment, right in the sitting room. He had seen far more shooting and dead people than he ever wanted.

He wished he could make a break for it and just go down to mani’s apartment, or next door to nand’ Bren.

“Can you talk to nand’ Bren’s guard?” he asked Lucasi and Veijico. “Are they there?”

“We are no longer permitted to use communications, nandi,” Lucasi said. “Regrettably, we do not have that access.”

“We should have it!” he said, telling himself he was going to talk to his father about that. But he dared not go out there.

He stood there, thinking these things, and aware that his bodyguard could do absolutely nothing to stop anything, not when it came from his father.

He heard the footsteps, his father and his whole aishid, by the sound of it, coming toward him, and he got back from the door, anticipating his father’s bodyguard to knock on it.

But they went right on down the hall, to about, maybe, the security station. And he immediately pressed his ear back to the door.

His father was going to ask security what had happened. That would be first. And with Lucasi and Veijico both here, his father was going to get only what Lucasi had already told him.

He hoped it was enough. He was in trouble. He was in really big trouble. And he tried hard to control his face and to look nonchalant about the situation in front of his bodyguard.

He went back to Boji’s cage, and Boji put his arm through the cage, reaching out with little fingers. He let Boji grasp his index finger, and Boji tried to drag it closer to his face, up against the filigree. That was not a good idea. Boji might still be in a bad mood.

He had no idea why it was so important to him to keep Boji. Except—Boji was his. Boji was alive, and noisy, and without him—this place would be like being locked in the basement in Najida, with no windows, nothing. He was not going to give Boji up. If the way his mother and his father could make peace was at the cost of Boji, he was going to appeal to Great-grandmother to take care of Boji for him. She might do that. Nand’ Bren might do it.