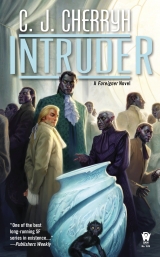

Текст книги "Intruder"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

But the paidhi had, Bren congratulated himself, done damned well thus far, getting Tatiseigi into a decent mood and having none of the guilds he’d approached express complete opposition to the proceedings between the aiji-dowager and Lord Machigi.

Ilisidi had—thank God—reported Baiji wedded and presumably bedded. Lord Geigi, who had not attended his nephew’s wedding, had meanwhile been very busy about Sarini Province affairs. He had gotten ink on the line in the agreement between his clan and the Edi regarding the exchange of land, and, via a paper Bren had signed before he had left, he had promised the assistance of both Kajiminda and Najida estates in the construction of the Edi settlement. The new center for the Edi would stand on a portion of Lord Geigi’s peninsula c little that Lord Geigi had ever used that sea-girt forested area. It was adjacent to the Edi holdings on Najida peninsula, and the combination would give them a tiny province of their own.

And great benefit to the aishidi’tat that agreement would be, once they could get that Edi treaty also ratified by the aishidi’tat, because if thathappened, the Edi were officially within the aishidi’tat, were officially committed to peace with the Taisigin Marid, and the Gan would follow.

And if there was peace with the Edi, then Machigi would be much, much happier with the situation he was walking into, and both sides would have recourse to the law and to the Guild for any breach of the peace. Which meant lawsuits instead of wars before assassinations.

That would be an improvement.

And in consequence of the committee meetings of the day, there had been, on Bren’s return to the apartment, a towering stack of reports waiting on the foyer table—the proceedings, requests, and comments of various Guilds and committees that had also met today, meetings that he had not been able to attend.

Plus, from his hardworking clerical office, there were reports for him to review: reports for Tabini, for Ilisidi, and for Lord Geigi, andfor the Guilds and committees—they were fortunately much of the same content, segments that could be broken out and sent to various subcommittee heads at need. He simply needed to look those over and send them.

There was a personal note from Geigi, arrived via the Messengers’ Guild, which confirmed what he had expected, that Geigi intended to be on the shuttle when it launched back to the station.

And—news—Geigi was coming back to the Bujavid and intended to be Ilisidi’s guest once Ilisidi got back from the East Coast. He would be here for a little time before he took that shuttle. And he would arrive on whatever day Ilisidi got back.

That arrangement would not work. And he was uncomfortable with the idea of his old ally Lord Geigi, who held an office equivalent to his, having to lodge downtown.

Inviting Geigi to guest under his roof, so to speak, risked awakening Tatiseigi’s general irritation that humans existed. And it might slightly ruffle Machigi, who had an ongoing issue with Lord Geigi. But it was an absolute necessity.

He and Geigi had business to discuss regarding the coastal estates, besides. So it did give them time to do that, in a crowded schedule.

And as he headed for his office, having instructed Supani and Koharu to move the masses of paper, Algini turned up from the security office.

“Machigi has just dispatched his representative, Bren-ji. Siodi-daja, of Jaimedi clan, is now in transit by train. She will arrive in Shejidan at sunset this evening. The Guild is prepared to assist her.”

Good on that score. Things were moving. Now everything would move. Fast.

“The shuttle is still on schedule?”

“On schedule, nandi. It will land within the same half hour as the lady arrives at the train station, so if you wish to meet one, the other is precluded. Weather is still good for a city landing.”

Generally the shuttle landings were further out, in respect to the city’s roof tiles; the space facility at the city airport had mostly plane traffic, moving personnel and freight out and back. But there was reason to land in the city on this one time, for security reasons involving its return flight.

“Notify Daisibi of the lady’s arrival, Gini-ji.”

So that the flowers would arrive fresh and have time to cope with whatever security the Guild had laid down.

And in this cascade of developments, and since the shuttle had chosen to come in at the old shuttle launch outside Shejidan, hehad the rare chance to meet the shuttle and welcome home Narani and Bindanda, whom he had not seen for a year, and to welcome the other members of his household who had been absent for two, going on three, years.

Tano and Algini would interface very efficiently with the Guild guarding the lady. He could send them to meet the lady as a courtesy. And with Koharu and Supani running the household here, he had no worries about dividing his bodyguard.

“If you, Gini-ji, with Tano, would be so gracious as to meet the lady at the trainc”

“Gladly, nandi,” Algini said. Algini was always anxious to be where the most interesting information originated. And that was with Lady Siodi, this evening, one was reasonably certain. One could lay bets that the Guild accompanying her would have a wealth of interesting things to say to the Guild establishment in the lady’s new quarters and to Algini that they would never tell to him.

“There will certainly be pizza left when you return,” he said. Their Najidi cook had very readily agreed to a dish this simple and festive for the dinner he was obliged to present to the redoubtable Bindanda, the master chef. The young man’s relief, when told that was the choice, had been extreme.

“We shall see the lady settled in good order,” Algini said. “And we shall get a report, Bren-ji.”

“One has every confidence,” he said.

So he saw the paper mountains sent into his office, and then he and Banichi and Jago went on to have their lunch, followed by a leisurely informal debriefing in the sitting room—Algini joined them there for an exchange of intelligence and a warning about the afternoon meetings. Tano came in with an account of reports sent to Tabini and messages received from him.

“The exhibit in the lower hall,” Jago said afterward, “is drawing attention not alone from the Merchants’ Guild. The public has seen the sign, and the news services have reported it. There is great public interest, and house security asks all households to be aware there will be tourist traffic in excess of the ordinary downstairs. At the museum’s request, the Guild is taking measures to provide a more extensive guard. The printing office, meanwhile, is doing special cards for the public.”

Keepsakes. Cards. Families kept such mementoes in albums, usually, along with their photographs, or hung very special ones on the wall, especially signed ones, and very especially ones with ribbons and seals of notable or memorable people.

And a card was being issued from the Bujavid Museum Office for the Marid porcelain?

God. That was going to bring out more than “crowds.” Mobs would be likely. A collectors’ item. A very high-value collectors’ item.

And, oh, the museum knew it. The museum would have the opportunity to collect beneficences for the eventcone was certain it would set up a contributions bowl beside the object. There would be lines at the front door. They would be putting visitors through in groups, guide-escorted and moved along at a set pace. All this while critical presession committee meetings were going on, while the Marid emissary was settling into her residence—and when the whole drama of the Marid alliance was about to go as public as any such event had been in years.

He should have seen it coming. He’d thought of a few rich collectors straying through. But—with the mix of recent upheaval in the south, the long-term public anxiety about the Marid, the distant news of a political shakeup, and now—now gifts from the new authority in the Marid, sent, for all the public knew, to the aishidi’tat itself—oh, yes, it made sense. At least in their minds, that gift was to the aiji. The news had twigged to the idea something was going on, and now there was an image they could broadcast that was becoming a focal point and a general public understanding that the agreement involved the whole aishidi’tat.

God,he’d dropped a stitch. No, he hadn’t avoided publicity. He’d intended to use it. He hadn’tplanned to be the lone representative of the powers that had been involved down in the south, with the business accelerating to the point of lunacy. Geigi wouldn’t be back until the dowager was; Machigi wouldn’t arrive until the dowager did. There was the Marid representative. There was himself. And what did he do with the pent-up potential?

He put up a damned art exhibit and thoughtlessly threw it open to the public almost as a matter of course. Allexhibits in the lower hall went public after their initial purpose was satisfied. They always had. Did now. He hadn’t ordered otherwise. God! He’d made a mistake.

“Does the aiji know it, nadiin-ji?”

“He does,” Banichi said. “He has talked directly with the Museum Director.”

“Who ordered the release of cards, nadiin-ji? The Director?”

“One assumes the Director, Bren-ji, but one can check.”

“Do, Jago-ji,” he said. “I fear I have involved Tabini-aiji. And I did not wish this.”

“One will inquire of the aiji’s office,” Jago said and left, probably to make a quiet call through channels.

He had wanted to make the porcelain, ergo the negotiations, appear in a popular light. Hehad wanted the piece displayed in a good light—literally—not hauled inelegantly out of a case and set on the conference table in front of the Merchants’ Guild. And after it had served its purpose, well, there was hardly anything to do with it but take it public, was there? He had expected the Director to put the piece in a quiet little case in the middle hall. If they were getting that kind of traffic, clearly it was not going to be in the middle hall. It was probably in the foremost display case in the foyer.

Printing cards.

He wondered if Tabini himself had quietly leaked the word to the public. He hopedc

But, God, Tatiseigi had no discretion in communications. If rumor had gotten out to some art expert, and then gotten from there to the porcelain fanciers, who were numerousc

“What have you learned?” he asked when Jago returned quietly. “Is the aiji greatly upset?”

“Bren-ji, it was the Guild that ordered it,” Jago said.

Bren blinked. And stared at Jago, who quietly poured herself a refill of tea and sat down.

The Guild had just intervened in a crowded printing schedule and had cards printed for a spur-of-the-moment art exhibit?

“One cannot ask,” Bren surmised.

“No,” Jago said, “one should not ask, and I cannot say more. But positive information on the agreement is being dispersed to many lordly households.”

God. The Guildwas backing the agreement. All-out backing it.

It made him nervous to have no check or objection whatsoever on what he was doing—nobody except Tatiseigi, who would cheerfully tell him his faults and flaws.

The notion that the Guild might be moving politics on its own again rather than supporting the aiji’s administrative authority—that gave him pause. Extreme pause.

In the light of what Tabini had told him—if Tabini had even told him all the truth—

God, what was happeningin the understructure of the aishidi’tat?

If the agreement helped pave the way for lasting peace, down the roadcgood. He thought so, at least. If they could get the state stable enough to rein in the Guild—he was associated with the very people who were capable of doing that and who were going to tell him the truth. He bet everything on that. And Jago, who’d just given him that information.

He just wished he were a little more confident that he was not setting something skidding into motion that had no damned brakes.

And he wished he were a little more confident in his judgment. The Guild was supposed to serve as a check on the aiji’s power. It was the law court. The bar. The regulation of societal stress and the court of ultimate appeal.

Had the recent bloodbath in the Marid and the prior battle, when Tabini had come back, and the one before that, when Murini had staged his coup—had those set-tos, in which far too many had died, been the tipping point toward a new theory of government?

Rule by the most clandestine of guilds was dangerous. No matter how good, how positive the intent, letting that go on was nota good thing. And of all people to have some of the major players in hishousehold—a human. The paidhi, who was supposed to be neutral in politics.

With Tabini-aiji’s bodyguard kept out of the loop because somebody lately playing politics at the top of the Guild had wanted to keep its operations secret and unstoppablecand didn’t trust Taibeni clan.

He didn’t approve. He very much didn’t approve.

“Nadiin-ji,” he said to them, “that may be good or bad. Let us hope it is good.” And he added, pointedly, “Keep Tabini-aiji aware. One asks.”

“We are watching,” Jago said. “We are watching all levels of this operation. Carefully. So are our partners.”

Algini and Tano.

“And we arereporting to Tabini-aiji, Bren-ji,” Banichi said. “So is Cenedi.”

Thatmade him feel better.

But not entirely. It meant that—should the Guild decide again that secrecy mattered more than law—it could decide to take measures against them.

Damn, he thought. Damn, he had to find out some things. He had to get uncertainty settled down, before things outright exploded.

The shuttle was on its way in, and meeting it required a train trip, a very pleasant trip in the closed quiet of the aiji’s red-upholstered private car, on loan again.

Meanwhile, the Guild reportedly had the Taisigi representative’s premises in ordercmeaning, of course, all the bugs were politely tucked in and well-concealed. Banichi and Jago professed themselves satisfied by the report they had from Tano and Algini, so one could take that arrival as going well. The clerical office had sent the flowers for the lady.

And for the rest, it was a smooth trip on rail out to the far side of the airport, until the train drew up to wait on a siding within view of the shuttle landing strip.

They had not long to wait. A call from ground operations advised them that the shuttle was now visible on approach.

One’s heart beat a little faster. Definitely. Even after a trip on a starship, these landings at the mercy of a planet’s unforgiving mass, involving so much support, involving weather, involving very high-velocity machinery, never became entirely routine. He got up and walked to the open side door to watch—he had on the bulletproof vest, as he had promised, a better-proportioned version and not so uncomfortable as the makeshift one. He stood in the light of a setting sun and spied the shimmering speck that was the shuttle. He watched it grow larger and more solid. He had landed on that very shuttle, and he knew everything going on in the passenger section, people taking last-moment account of any stray items. When the shuttle braked, it braked.

Wheels touched. The nose came down elegantly, and it slowed and braked, using up a scary lot of the runway.

Now it was simply a matter of waiting while the support vehicles moved in, while the exterior cooled a bit, and the safety crew had a go at the craft.

Inside, the passengers would be shifting about, gathering up their hand luggage, and the shuttle crew would be putting the shuttle into a safe condition for its two weeks or so of servicing and checks and refueling—the normal schedule for any shuttle on the ground.

Well, the show was over. Now it was all waiting. Bren returned to his seat as Banichi and Jago shut the door. They shared a little tea, it being close to suppertime, while Jago kept an ear to ground operations and Banichi kept track of events downtown in Shejidan.

“The Marid representative has reached her apartment, Bren-ji,” Banichi reported, “and Tano and Algini have met the lady, who expresses gratitude. She is quite pleased with the apartment and office and is particularly pleased to find an excellent and approved restaurant across the street, which is arranged to provide menus and deliver to her premises.”

“Excellent,” he said. He was entirely relieved. Two things were going well at once. Unprecedented.

He sat and sipped tea, while Jago followed post-flight operations. At last she advised them that the shuttle doors were opening and that a bus had been dispatched to convey the passengers and their baggage directly to the train, customs waiving an inspection on executive privilege.

Bren gave it a few minutes more, and when Jago reported that the bus was well on its way to the siding, he got up, set his own teacup in a safe enclosure at the back of the galley counter, and went back to the door with Banichi and Jago.

The modest spaceport bus came purring up alongside, next to a low ditch and blooming water flower. It stopped and opened its door, lowering its steps with a pneumatic hiss.

Out first came a young man: young Casichi, one of Narani’s many nephews, and then, white-haired and moving slowly with the young man’s help, Narani himself, who looked up with a wide grin.

Immediately after Narani came the portly and distinguished Bindanda. Then—was that Asicho, or Sabiso? Asicho, Bren decided, the excellent young woman who, with Sabiso, had attended Jago’s needs in their very male household aboard ship—the two were partners and cousins, as alike as sisters; Sabiso was right behind her.

And Jeladi! Jeladi, his sometime valet, who had been their man-of-all-work aboard ship, who now would assist Narani at the door and with the accounts.

Then came Kandara, and Palaidi, and Junaricall, all welcome and happy faces, men who had been on a grand adventure and now might have—finally—a chance to visit their homes in Najida village.

Bren descended a step. But Jago put a hand on his shoulder.

“Narani will need assistance, nadiin-ji,” he protested.

“Then you must stay here, nand’ paidhi,” Jago said firmly and primly, “freeing your bodyguard to do that service.”

Wherewith, she easily skipped to the ground as the senior company from the bus made their way toward the train. The younger members of the company had started offloading their bulkier stored baggage, a great deal of it, from the bus.

There would be gifts for family, all manner of mementoes of their service on the station—one could by no means handle such things roughly or without consideration. Banichi got down and headed for them to assist.

Narani reached the bus. And with these people, hang back as he must, Bren had no solemn formality at all. He offered Narani his hand for assistance up the last step, took a good grip on the door frame and assisted Bindanda—who had not lost any of his girth—and one after the other of the others. Banichi and Jago arrived hindmost, shepherding the baggage handling, and they and the younger folk heaved their loads up into the car in a happy and noisy chaos. Atevi on public occasions showed very little emotion, all stiff formality, but there was none of that reserve in this moment: everyone fairly beamed with happiness, even Bindanda, and most of all gentle Narani. Hugs were out of the question. There were simply deep bows, repeated deep bows, and very, very happy staff, while baggage was shifted and people found seats.

“Nandi,” Narani said more than once, “you do us very great honor. One by no means expected the paidhi-aiji to come in person.”

“I would have walked here barefoot to see you, Rani-ji, and you, Danda-ji, and all of you, and you know it! Welcome back! Welcome home! We have made our bestefforts to put things in order in the apartment, as best we could, with the help of some young folk from Najida, and a young cook, Danda-ji, who is terrified of meeting you and so much hopes to have your good opinion. And by no means shall any of you delay meeting family. If any of you– anyof you—have urgent need to visit your own houses for any reason, nadiin-ji, we shall make every effort to get you there and back again; and you all, in precedence of service, may have a week in Najida, at your pleasure and my expense. Nadiin-ji! One is so very, very gladto see your faces again!”

There were more bows. Protestations that none of them, not one! would leave until the household was in good order.

“You all resume your rank and your duties,” he said, “except, Jeladi—”

“Nandi!”

“You know your circumstances, that you will assist Narani-nadi!”

“Yes, nandi!”

“One has the greatest confidence, nadi! Sit, be at ease. We have every sort of beverage and fruit juice. But mind, mind, we shall have pizza on our return to the Bujavid, and you must arrive in good appetite!”

That roused a cheer. Fruit juice was the overwhelming favorite choice, and the youngest took over service. They had at least two rounds before the train began the careful climb up to the Bujavid train station.

From there it became a traveling celebration, a laughable effort trying to get all the baggage into the baggage office, and arranging to transport it themselves.

Upstairs, then, in more than one elevator load, their advance guard reached the front door—where Supani and Koharu met them. Koharu with some little ceremony turned over the keys to Narani right from the start. “An honor to do so, nadi,” Koharu said graciously, and with that, Narani resumed the post that was his.

Bindanda, now—Bindanda sniffed air redolent of fresh-baked pizza and said, with extraordinary charity and good humor, “The paidhi seems very ably served in the kitchen.”

Which was not to say Bindanda did not immediately head down the hall to the kitchen in his shirt sleeves, having handed off his outdoor coat and not even having changed to kitchen whites, bent on inspecting the kitchen operation.

Tano and Algini had made it back to the apartment not long before them. “Go rescue Pai-nadi, nadiin-ji,” Bren said to them under his breath, for fear their young cook would simply wilt at the sight of Bindanda, and those two headed toward that venue on a mission of mercy, right on Bindanda’s heels.

Supani and Koharu having gotten back to their own assignment, however, the hated vest could now come off, and Bren slipped on a light coat for house wear, while the staff settled into their rooms backstairs. It was suddenly a completely staffed household, a lively household and a happy one, even in the kitchen.

And within the half hour, pizza began to pour from the kitchen to the dining room in an extremely informal service. It was the atevi recipe—green, laced with alkaloid, all except one special one. It was a dish that newly established custom declared proper to eat standing, with drink in hand, even while touring the premises on a festive occasion. Even Narani put away three pieces and Jeladi certainly more than that—not to mention Bindanda, who must have accounted for one entire pizza himself, to Pai’s great delight.

Then staff, having toured the revisions to the apartment, settled on available chairs in the sitting room—and long past supper and an offering of brandy, they all traded stories, stories of life on the station during the Troubles and stories from the Najida folk of how they had stolen the paidhi’s furniture from the Bujavid—details that Bren had not himself heard, and he had to laugh at Koharu’s account of getting a room-sized carpet past two guards.

It was a splendid evening. Everybody got along famously, and everyone drank a bit more wine and brandy than proper; there was laughter, and good humor, and in due time—bed and quiet.

“Such a day,” Bren said into Jago’s ear when they were both abed. “Such a good day.”

“In every respect,” Jago said, and sighed.

10

Morning. And in Father’s household, unlike mani’s, they all almost never had breakfast together. Or lunch. Sometimes they had supper. Every few days they had supper.

But it was a surprise to be asked to breakfast with Father and Mother. At first one feared one’s parents had found out about Boji.

Cajeiri scrubbed and dressed and turned out in his best, all the while asking himself what other bad thing could happen or how he would handle it if his worst fears came true.

But once he entered into the dining room, he was perfectly cheerful. He had learned from Great-grandmother never to let worry show on his face, because then there would surely be questions about one’s bad mood, and then one would be obliged to tell much more than one wished and end up defending oneself before ever being challenged.

If the two servants he had tending to his apartment had taken a report about Boji to his father, he was going to be more than put out.

But again, one dared not let worry show. One just appreciated the breakfast, which was very traditional and actually quite good, and thanked the cook. And tried to be smart.

Since nothing came up after service was done, he decided it could even be one of those times when his parents had decided to notice him and have breakfast with their son the way other families did.

If that was the case, that was nice. Or it would have been nice if he had anything entertaining to say. Mother and Father had talked about the legislative session and the Communications Guild, while he tried to keep a pleasant expression throughout that dull stuff, and when after-breakfast talk was done, he decided he might be able to just slip out quietly and go about his own business.

“Son of mine,” his father said, stopping him halfway to rising.

He settled. “Honored Father.”

“Come to my office.”

This was not good. Not at all good. It could be about lessons. But he and his tutor had gotten along.

Maybe that was all Father wanted to ask him: how the tutor was doing. He would say, I want this tutor, and his father would say that was fine and let him go.

His father and mother went their separate ways in the hall; his mother remarked on his coat and cautioned him not to wear it except on special occasions.

“One thought this wasa special occasion this morning, honored Mother,” he said, which brought a little frown to his mother’s face.

“Well, we shall have to do it far more often,” she said, which was not what he wanted to hear. And she patted his shoulder and then went her way to her suite, while his father had already walked on into the main hall with two of his bodyguard in tow.

Cajeiri had not brought his own guard to stand duty at breakfast, it being inside the apartment. But when he got to the office, his father’s guard took up their posts outside, and one opened the door for them, and shut it when they were inside. It gave the visit an uncomfortably formal feeling, as if he were some kind of offender being brought to court.

“Well,” Father said, settling into his chair at his desk, with stacks of papers and books everywhere about that were mostly classified, and with the important business of the whole world spread about them. “You do look very fine this morning, son of mine.”

“Thank you, honored Father.” It called for a bow. He made it, hoping hard that this really was only about the tutor and his lessons.

“You are still content with your tutor.”

“Very muchso, honored Father.”

“A wonder. One has also a good report from him.”

“One is gratified, honored Father.”

His father turned to his desk and took up a small, fat envelope. It was a curious envelope. It had that glassy kind of look that did not belong on earth. It was so transparent one could see writing on it. His father laid it in the midst of his other papers. He wished he could read what it said at this distance, but it was impossible.

“The shuttle has landed,” his father said, “and brought with it a letter.”

His heart had already picked up its beats. Now it beat faster still, but he was not sure whether he was in trouble or not.

“A letter, honored Father.”

“You sent a message, this time by Lord Geigi.”

Faster and faster, and with suddenly far less hope of possessing that letter. He was definitely in trouble, maybe Lord Geigi was, thanks to him, and quibbling would not help matters. “Yes, honored Father.”

“You are determined, are you not, to keep up relations with your associates on the ship.”

“These are valuable associates, honored Father.”

“You think so. They are not the sons and daughters of aijiin. They have no connections.”

He had never heard that objection to his associations. He had never even considered that objection. And he pounced on the only logic he could think of.

“The ship-aijiin have no children, honored Father.”

“You know that, do you?”

“None my age, at least, honored Father. But—”

“Continue your thought. One wishes to hear your reasoning.”

He had never reasoned any logic for his choice of companions, except that they were accessible. There had been more kids, but a handful—a handful were the best ones.

“They have good qualities,” he said. His head had gone spinning off into ship-speak, and it was hard to find words in Ragi to describe these associates. “And they are valuable.” A thought struck him. “Nand’ Bren is not the son of an aiji, is he, honored Father?”

“He is not,” his father said. “Humans form their associations differently. Yet one might suggest that you are a more valuable associate for them than they to you.”

That envelope was aboutGene and Artur and Irene and Bjorn. It could be fromthem. But if he asked for it, his father would probably say no, and that would be the end of the discussion for years. So he fought to think straight, and not to panic, and not to lose his words. (Lose your words, his great-grandmother would say, after thwacking him on the ear, and you lose your argument. Lose your argument, and you lose what you dearly want. Think, boy! Whatare your words?)

“Humans form their associations differently.” He answered his father with his father’s own words. “They do not have to be the sons and daughters of aijiin. I makethem important.”

His father blinked, at least a sign that he was impressed. “And they have good qualities, you say. What are these qualities?”

“They are clever. They are forward. They know things.”