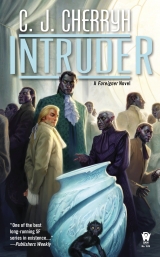

Текст книги "Intruder"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

He was much, much happier with that thought.

And he had no fear anyone was going to come in here and read the calculations of his map. It was not that evident what it represented, that was one thing, and he had just secured his rooms, with the loyalty of two servants whose future—it was not stupid to think—lay most securely with him,even if he was only infelicitous eight.

He was so soon to be nine, probably before his sib was born; he absolutely refused to share his birthday.

The plane touched down and rolled to a stop in the dark, the blue field lights obscuring any view of Shejidan. They were almost home. For luggage, there were only the carry-bags for classified Guild equipment, a little extra luggage of Bren’s, and the two fair-sized crates Machigi had sent. Airport security staff and workers under their supervision moved up carts to manage the crates and get them into the waiting van. Jago carried Bren’s bag as well as her own, and they all descended from the plane and boarded the van with the efficiency and speed of a routine arrangement.

It was a fast trip across the field, over to the open-air airport train station, then into a small enclosed platform where a Special waited—only one passenger car was attached, this trip, and plus the baggage car, and Guild security held both ready for their boarding.

The crates had to be loaded to baggage; Algini stayed to supervise that, while the rest of them climbed aboard the passenger car—Tabini-aiji’s own car, with dark red velvet curtains making the inside much nicer than the all but windowless outside. It was the same bench seat at the rear that Bren always took, and it was like any return from Mospheira. Any visit to Malguri. Any visit to Taiben—going back for years and years of service to Tabini-aiji.

At the start of it, he’d flown where they could find room for him and hung about reading and doing work in a cubbyhole, waiting for some train from the Bujavid hill to pick up groceries and afford the paidhi-aiji a seat somewhere.

Bren let go a slow sigh, as, without even asking, Jago handed him a fruit drink from the well-stocked little fridge this luxury car afforded. It was innocent of alcohol—a good call. God, he was tired. Physically tired, but not so much as mentally tired.

And he was finally past the point of needing his wits about him. That was a relief. His wits had had all the exercise they could stand.

He felt he was already home as the train began to move. He knew every turn in the track from here on, and he saw relaxation slowly set into his bodyguard as well, everything became as predictable and as safe as it ever could be.

Not to depend on, however. The news was probably leaking out about the Marid contact. Thatwould racket through the rumor mill. It would touch off crazy people. And animate sane ones who had opposing interests.

The bullet-shield curtains were drawn on the one window that actually was a window; they almost always were drawn. If they hadn’t been, at about this turn, one could have seen the Bujavid on its hilltop, rising up and taking with it some of the mazy tiled roofs of the city. At the bottom, one would see one little spark of outrageous neon at the limit of the classic Old City neighborhoods—and he’d just as soon not see it. He’d been wanting to get that neon display in the hotel district outlawed for years, but he’d never quite found it worth the fight with the very party that generally supported him—the innovators, those who favored human tech and humans, and happened to think neon light was a great tourist attraction.

Another familiar turn about the hill and the train diverted onto the track that only a few trains, and mostly this engine, ever took, the line which led into the tunnel of the Bujavid hill itself.

Still more turns—he was down to the bottom of the fruit juice now. One could tell by the sound and by the reduction in speed, exactly where they were, every detail of the system as they slowly climbed toward the Bujavid train station.

Algini and Banichi silently got up and went back to the hand baggage. Tano, one arm still somewhat impaired, made a move in that direction, pure habit; but Jago got up, put a hand on Tano’s good shoulder, and went back in his stead to help Algini and Banichi. Tano settled again, looking annoyed.

“How is it, Tano-ji,” Bren asked him, “after the flight? Was the pressure change a problem?”

The frown persisted. “Nothing of consequence, Bren-ji.”

“Hurts, then.”

“Not much,” Tano said, moving the shoulder. “It needs exercise.”

“Prescribed exercise,” Bren said staunchly. “And sleeping in your own bed tonight, Tano-ji.”

“Indeed,” Tano said more cheerfully. “And you in yours, Bren-ji. Well-deserved, in your instance.”

The train slowed and slowed further, coming to a halt at a platform Bren could see in his mind. They stopped. The door of the car opened.

Bren took his case in hand and got up. Tano did. They walked back to the door as Banichi opened it, and, behind Algini and Jago and Banichi handling the baggage, Bren stepped down to the platform—a fair hop for a tired human. Just as automatically, Tano reached out his good hand and steadied him in his landing beside the baggage.

“To the lift,” Banichi said, indicating he should not wait about. It was an area crowded with idle carts, offering only freight lifts, not the ordinary passenger siding. Freight had come in recently on another train; crates of seasonal vegetables, probably eggs, and sacks of flour sat on the other side of the platform, at the other freight dock. Their own engine would be in motion again once it had given up its last baggage, moving to stand ready, though reversed on the track, for Tabini’s own occasional use. There was no other inbound traffic at the moment, just a stack of personal crates on the passenger platform indicating that someone else had arrived in the residencies, bringing furniture with them, by the size of the crates—not an uncommon event with the legislature about to go into session.

They left Algini and Tano to arrange things with the crates. Banichi and Jago took their own hand baggage, a light load for them, and they headed toward the quieter area of the platforms, where the lift shafts made a vast pillar, the spine of the hill, going up and up from here. There were the lifts, a bank of them, along with the pipes and conduits, the veins and arteries that carried everything that came from or went into the Bujavid.

There were not many passenger lifts, and none these days went above the main floor or the offices. Banichi and Jago held the door of the one waiting—no lift was going to budge with Banichi in the doorway—and Bren walked in.

Banichi got in. The doors shut. The car went up and up, a considerable rise to the floor of offices above the legislative halls. There, observed and recognized by the guards on duty, they took themselves and their baggage across to another lift and rode up to the third residential level.

The doors opened quietly and let them out into an elegant hallway of antique carpet runners, porcelains on pedestals, crystal chandeliers, and a sparse choice of individual doors on either handcamong which, to the right, was, finally, his own apartment, a direction he hadn’t taken all year, not since he’d come back from space.

Home. No more Farai clan holding the place hostage. And no more making do as a resident with someone else’s staff—well, there would be a little making-do, for a few days yet, since they hadn’t a master cook, hadn’t all the furniture back, and hadn’t full staffing yet. But that was coming.

And Najida staff was waiting for him, some of whom, including his valets, Supani and Koharu, had a permanent appointment. For the rest, which he very much looked forward to, the very next shuttle flight would bring staff from the apartment on the station—people sorely missed, some who’d flown to deep space with him; and who hadn’t found it possible to get a flight down to meet their own kin on theirreturn, nor for the whole year since.

Oh, one could sogratefully do with a little dull tranquility and normalcycat least as much as one could find in an apartment right next door to Tabini’s, and not that far from Lord Tatiseigi and the aiji-dowager, not to mention just upstairs from the legislature, the aiji’s audience hall, the committee offices—

And not to mention, upstairs from his own clerical office, which had reconstituted itself in the last year and was again swamped with correspondence.

Plus he’d have the news services to deal with by tomorrow—but the news people couldn’t get access to the Bujavid train station or the upstairs of the Bujavid.

Maybe he could manage a few days’ respite. Sleep. Sleep would be good. Sleep under his own roof, so to speak, and with no pressing emergency.

They carried their baggage to their own front door, and they had not even to knock. The ornate doors swung inward from the center, both leaves, and let him and his travel-weary bodyguard all in at once.

Staff waited in the foyer, people from whom they had parted only a few days ago—but all in new jobs and a new place, with smiling faces and happy enthusiasm.

“Nandi.” Supani, his major d’ pro tem, immediately helped him off with the traveling coat. Koharu took that garment from Supani and handed it on to Husaro, who whisked it out of sight for cleaning, to be ready if needed in the morning. And immediately there was a simpler, lighter coat for indoors.

Thus clad, he went doggedly through the company, naming names down to the very young chambermaid, meeting each, thanking them for coming. To the lot, then and especially to the girl, who was only fourteen, he said, “Do advantage yourself of the post whenever you wish, nadi. Send as many cards as you need. One understands several of you are for the first time in the city. So you all must take hours off and go take tours. Go as several together.”

“Nandi,” was the general murmur, bows, diffidence, delight. “Nandi, thank you.”

His bodyguard were due a rest of their own; Tano and Algini had yet to arrive with the baggage, but they would be here soon.

He was obliged to take a tour of his own apartment, which the staff had labored to render habitable, freighting furniture in across country from the Najida basement, finding linens, stocking the kitchens, installing his wardrobe and his personal items, his libraryc

These brave people had saved so much that was his from the predations of the Farai, and it would take hours to go through the library alone and find out which of his books had arrived. He had to inspect every room, admire it, assure one and the other anxious staffer that it was perfect. He was tired, but they had shepherded his belongings back, in some cases having risked their lives stealing it away before the Farai had moved in two years back.

So, yes, he did admire it and all their ingenuity. First of all was what was new: a guest room the apartment had never had. It had appeared in the reorganization of Tabini’s apartment and the redefinition of the sitting room wall and foyer—due, they all understood, to the elimination of a servant passage which had been declared a security hazard to Tabini’s apartment. Tabini had gotten a storeroom out of the transaction, but the paidhi now had guest quarters—small but elegant, with furnishings his staff had picked out, tasteful and classic and very fine.

In the Bujavid, where space was at a premium, it was a miracle, an incredibly generous gift, especially considering the donor, and his staff was absolutely delighted and proud. They hoped the furnishings they had chosen did it justice.

He pronounced it very fine, very fit, and they were happy with that. He went on, finding some things back in their proper places. There might be a new couch in the sitting room, but they had gotten the tapestries away and a room-sized carpet, of all things—the ingenuity and courage involved was memorable. They had saved his modest china, but they had ordered in a new dining set. They had insisted on replacing the pots and pans and all the food, saying that they would trust no utensil or store that the Farai had used and left.

His office desk had a broken lock, but that had been repaired. His shelves were again full of his books and a few mementos he recognized from Najida.

There was the security station, part of the suite Banichi and Jago had already occupied—they were in communication with Tano and Algini, who had just returned to the Guild office some of the armament they had brought back, not quite appropriate for defense in the Bujavid.

And above all, there was that wonderful bath, just as he had left it. At the moment he wouldn’t care if there were Farai currently sittingin that great tub. He had to have his bath, to clear the way for his aishid to use it, and he said finally, with the tour now reduced only to Supani and Koharu, “Nadiin-ji. I am absolutely exhausted.”

“One anticipated so, nandi,” Supani said. “Cook has arranged a light supper for you and your aishid, when they wish.”

A light supper for a late arrival. It was his standing instruction at Najida, and it was perfect for tonight. This staff knew him. This staff understood him. Everything happened by magic. His world was in perfect order: he had a bath waiting, and they would, once Tano and Algini were in, shut the doors definitively and be one household, safe and secure, beyond reach of anyone.

The bulletproof vest fastened under the arm. He shed that overheated confinement with an immense relief. Supani and Koharu reverted to their true and proper jobs, being his valets; Koharu took the vest away to be cleaned, and within a little time he was neck-deep in steaming water and very, very content with the world.

“Shall we leave you, nandi?” Supani asked. “Or would you prefer we stay?”

“Stay, stay,” he said. “Tell me everything.”

So Supani and Koharu sat by informally on the bath benches and chattered on about the staff’s adjustment to the apartment, about the pot and pan situation, and the fact that Pai—a lad from Najida kitchens, not quite a sous-chef, but ambitious and willing—had gone bravely down to the city and bought the essentials along with the groceries, independent of reliance on the Bujavid storehouses, to which they did not have an authorization, an action which it was hoped would be approved.

“Excellent,” he murmured, eyes shut. “And furniture for the staff quarters, nadiin-ji—you are well provided for, one hopes.”

“We are all perfectly content, nandi,” Koharu said. “We are a little short of beds as yet.”

Eyes open. He sat up in the bath. “Oh, this will not do,Haru-ji!”

“Beds are coming, beds are coming, nandi. By the time the staff from the space station arrive, everything will be kabiu and orderly in our quarters. We have only two people as yet unprovided for.”

He sank back again, up to his chin. “One hopes, nadiin-ji. I cannot accept that my staff is sleeping on the floor.”

“We are quite comfortable, nandi, for the time being. Two have doubled up. We have most excellent facilities—those were renovated, too. We have never lived in such modern surroundings.”

“You are content with that.”

“We are very content. We have every convenience.”

They were from a fishing village. A place of great tradition. His apartment was scant of history, but it had some things in which they could take great pride.

And he would have to get a list of what was still needed. For two, going on almost three years now, he had been away, either on the station, the ship, or living a hall away, on Lord Tatiseigi’s charity.

Now he was back in a place utterly dedicated to keeping the paidhi-aiji functioning and doing his job. He had anything he wanted. More money than he could possibly spend, even considering he was renovating Najida, and bringing improvements to Najida village, and assisting with the Edi’s new manor house.

And it was an extraordinary staff, who had left their kinfolk in Najida to come to a city where they knew absolutely no one, only to keep the lord of Najida in comfort. He owed them. He owed them the best he could possibly provide. They, in a different way than his bodyguard, kept him safe and functioning.

“You should each have whatever you wish,” he said. “Just let me know what you need, and I shall sign for it with the Bujavid storage.” He slipped beneath the surface, where all was quiet except the circulating pump, and resurfaced for air, in good humor.

“We truly need very little, nandi.”

“Beds, Haru-ji!”

“It is by no means so grim as that, nandi,” Supani protested, laughing. “Bujavid staff has been very helpful to us. So, one should mention, has your office, which has written orders to have the water and electrics, the proper certificates for maintenance, all these things in order. We have moved very fast, thanks to them, from a complete shutdown of services.”

“Indeed.” His office staff downstairs. His wonderful clerical staff. Another set of heroes of the bad years, and of his time in Tatiseigi’s apartment, and on the coast. The clerks had saved records and handled what they knew how to handle, at times in secret, very dire messages, while in hiding and in fear for their lives—so far as they could, they kept the network connected that had helped bring Tabini back to power.

“All the same, I shall sign any order for staff comfort that crosses my desk, and I place you two in charge of the matter. I hold you responsible for tour groups to visit the city.”

They laughed gently. He ducked back under the perfect water and enjoyed the sensation of the currents.

Perfect. Absolutely perfect homecoming. What more could he possibly ask?

It was a quiet supper of toasted sandwiches he and Jago shared in bathrobes, not in the dining room but in the foresection that was the breakfast room. Tano and Algini and Banichi were in the bath at the moment. It was the men’s shift, Jago having had the tub after him.

And after that delightful supper, which put Jago into a laughing mood, they were bound for bed—until Supani came in to report that the two crates had arrived.

Jago insisted on checking those personally, to be sure they were indeed their crates and, as Jago cheerfully put it, to be certain the porcelains from the Marid were indeed porcelains and nothing but porcelains. They had scanned the crates and found no metal, but she wanted to be sure.

“Do not send the packing away, Jago-ji,” Bren told her. “Tell me when you have them unpacked. We shall be sending them on.”

And Supani reported, too, since they had come to the foyer, that a message from Tabini had arrived during supper, which did need looking at.

It was, perhaps, a mistake not to ask for that message only. One should never, ever check the general mail just before bed. It only led to things one did not wish to know and questions that would keep one from honest sleep.

But curiosity began to niggle away. “Bring all the messages,” he said with a sigh, while Jago and two of the servants were unpacking the porcelains, he sat at his desk in his office and continued to sip his tea until Supani came back with the message bowl.

The bowl was, not unexpectedly, full.

The note from Tabini, unrolled from a red and black message cylinder, began with a courtesy, felicitations on his recovery of the apartment, wishes that he might enjoy the added space, and an order to meet with him next door at the first business hour of the morning. That was not an unexpected summons, either.

The rest—he sorted. He laid aside the messages arriving in other familiar cylinders, some official, from committees, some not—various people who would, one expected, simply be offering courteous, routine felicitations on his safe return. There were a few cylinders from various ministries and committees; those would be all official business, and that lot went back into the basket. Transport and Trade were in that number. They would be requesting meetings at the earliest—he didn’t need to open them to know that. In fact, he had already provided information to those offices regarding the Marid situation, and he needed to meet with them, first on the list of committees. But not tomorrow.

One cylinder bore his own white band. That, he opened. It was from his own clerical office, beginning with, We rejoice, nand’ paidhi, at your safe return,and ending with, There are a few situations in which we may require instruction, and we look forward to receiving your personal direction.

One could bet they looked forward to being inside the information loop instead of putting out fires. They’d been putting out those small fires ever since his unscheduled vacation on the coast had started, he was sure, since that was what they did very effectively—but they were surely weary of delivering the same boilerplate promise to all comers as the crises began to mount : The paidhi will attend to this matter when he returns.

Theywere the office, ordinarily, that prevented him having a message-bowl completely spilling over with messages from ordinary citizens, as mundane and heart-warming as schoolchildren requesting factual answers for their homework, the occasional bewildered individual concerned about holes the shuttles were said to make in the atmosphere, or some citizen warning him of some dire prediction to flow from a committee meeting, a portent their grandmother had found in adding the birthdates of all members likely to attend.

But he could bet, too, that some of the messages that gallant crew had been fending off in the last week were a good deal hotter than the routine. Bullets did not fly and former enemies did not change sides without agitating certain people in positions of power.

And, an item Supani and Koharu would not yet think of arranging and that Narani would certainly not have forgotten, were Narani here yet: he had to talk to Daisibi, head of his clerical office, and be absolutely sure that every committee meeting he was scheduled to attend had an appropriately felicitous flower arrangement at all times. He also had to engage Bujavid security to be sure that no political agent adjusted a display of flowers in any infelicitous fashion. He was back in the land of innuendo, and he had not dealt with that aspect of things in a while, having had Tatiseigi’s very capable majordomo micromanaging his affairs—until now.

Now he needed all the help he could get. He could not expect Supani to understand the ins and outs of political trickery, and he just should not set up appointments on the fly, not until Narani, who was old and canny in these matters, got down from the station to take over.

God, but he surely didn’t want to go down that mental track of detail and detail right before bed.

Talk to his office manager. That was the necessity. Be sure every prospective appointment went through that worthy gentleman, Daisibi.

And quit trying to manage the details himself.

One plain little cylinder remained in the bottom of the bowl, a copper one, topped with a bit of amber and a little fatter than currently stylishcthe sort of thing a businessman might use; it was odd that his office staff let such a thing through to reach him.

The letter inside it brought a smile. He knew that carefully rounded handwriting at first glance. And it was no business solicitation.

It was the aiji’s son.

Cajeiri of Ragi clan to the paidhi-aiji, the Lord of the Heavens, Lord Bren of Najida district.

Please may we share breakfast in the morning, nandi? It is a personal embarrassment that I have no kitchen or dining room to be able to offer, but one would be happy to see everyone at breakfast if you could please invite us. It is very boring already, and you will be too busy.

This letter had to be answered. He took paper and pen, lit the waxjack with a match. and wrote, briefly,

Lord Bren of Najida to Cajeiri-nandi.

It would be the greatest honor to see you at breakfast tomorrow at sunrise. Your bodyguard will also be welcomed to table.

Supani was, typically, not far from his summons. He rang a gentle little bell and delivered one of his silver cylinders, with his own wax seal, into Supani’s hand. “This invites young Cajeiri to breakfast at dawn,” he said. “Deliver it to the aiji’s staff. And do mention to that staff that I have indeed read the aiji’s note and shall be on time for a meeting, so I may be added to his appointments tomorrow.” It was more than likely that his bodyguard had already heard from Tabini’s bodyguard and had intended to tell him in the morning, maneuvering him toward that appointment by arranging his breakfast call at the appropriate time, but everybody was tired, and twice done was better than not done at all. “Tell Cook Cajeiri-nandi and I shall have breakfast in the dining room, with my entire bodyguard and Cajeiri’s, at table together.”

“Yes,” Supani said, and was off to help staff work the magic that always delivered a lord, even a very young one, appropriately dressed, at the appropriate hour, in the appropriate place, and got another very sleepy lord out of bed and dressed for the day, with a breakfast readyc

That was assuming that Tabini let the young rascal come, once the staffs got their information together and told Tabini. It was by no means certain that that initial message had traveled through Tabini’s staff at all on its way to his door and to his staff.

But he honestly hoped that the boy would be allowed to come. And it was a very good guess that the young gentleman would be as happy to see his bodyguard as to see him. If he seated all four of his own bodyguard at breakfast, then courtesy obliged him to extend the same invitation to Cajeiri’s young bodyguard—it would embarrass hell out of the youngsters, likely, whose rank in the Guild did not near approach that of his staff, but it was not as if they were strangers to each other.

Supani left. Jago came to the office doorway to report everything had arrived in good order, unbroken. And with that information, Bren took another of his own message cylinders and wrote a second letter, one he had intended to handle in the morning.

Bren paidi-aiji to nand’ Tatiseigi, Lord of the Atageini,

One rejoices to be back in the Bujavid again, this time in one’s own premises. One will never forget the kindness of your excellent staff and, most of all, the graciousness and generosity of the lord of the Atageini—in gratitude for which one extends a cordial invitation to an informal supper in my modest dining room tomorrow evening. One hopes you will accept such an offering, along with a gift in token of my profound esteem and gratitude for your hospitality.

The gratitude was real. So was the urgent need to talk to the old man before Tatiseigi wound himself up for a fight over the negotiations in the Marid.

He hadn’t personally seen the porcelains. He took the second message cylinder with him to the foyer and found the two massive porcelains set out carefully on the floor, in a scatter of straw and other packing.

My God, he thought at the sight of them. He’d thought the weight, which had made loading them on and off the plane a job for a lift, was mostly the wood and packing. But they were amazing, each of the two a complex weight a human would lift with caution—each a delicate and extraordinary spiral of sea-creatures that imitated the ones on the great pillars of Machigi’s hall, and executed with the hand painting and the glazes that had made Marid work important to collectors across the continent.

They were extravagantly expensive works of art, and there was little to choose between them.

If thisgift didn’t mollify the old lord and set him a littleoff his balance, there was no dealing with the man. He was personally embarrassed that he was this beholden to Machigi.

But there it was.

He made his choice. “Set them both back into their crates,” he told the staff who had been cleaning them of dust. “And deliver the one nearest me tonight, in my name, to nand’ Tatiseigi’s apartment. Advise staff it is extremely fragile and irreplaceable. Then in the morning, after breakfast, deliver this letter.”

A crate, arriving late in the evening, when likely the old man was abed, would get staff attention, and at very least Lord Tatiseigi, a notorious early riser, would see the gift before the sun rose. Madam Saidin, Tatiseigi’s major d’, would see to its proper handling and safe situation, he was entirely confident.

And if he knew Tatiseigi, Tatiseigi the collector would have set his heart on permanently owning that porcelain several heartbeats before any other consideration of indebtedness for the gift occurred to him.

He ordered the recrated porcelain set at the door, dispatched staff to get a dolly, and laid the letter on the foyer table, trusting his orders would be very precisely carried out.

And he went back to his office and wrote a third letter, rubbing his eyes the while and trying to be extremely accurate in phrasing.

Bren paidhi-aiji, Lord of Najida, Lord of the Heavens, to Master Hadiro, Director of Exhibits and Curator of the Bujavid Museum, with respect and honor.

This object is offered for initial private exhibit in the lower hall. Please see that it is available for viewing and that the Merchants’ Guild is specifically invited to its first showing.

Then, tomorrow afternoon, please set it in the public exhibit hall as a gift from Machigi, Lord of the Taisigin Marid, to the people of the aishidi’tat.

One appreciates the extraordinary effort this will require on very short notice and hopes that the piece, on public appearance, will find easy felicity within your arrangements. The arrival of this piece from the Marid had no advance notice, but it has extreme political sensitivity and appears at the request of the paidhi-aiji, in the efforts of peace with the Marid, which should be the theme of this exhibit. One dares not use the seal of the aiji himself, but the paidhi-aiji believes that consultation with his office will assure your office of approval for this exhibit.

Note that the style imitates the famous set of pillars that grace the audience hall in the Residence of Tanaja. The original blues cannot be reproduced—the ancient process relied on a pigment lost when the Great Wave altered the north shore of the Southern Island, but a replica pigment has been used.