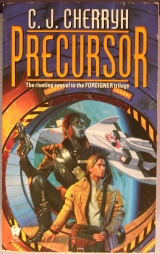

Текст книги "Precursor"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

“And atevi,” Bren said. “Atevi aren’t immune to it.”

“Living a fantasy is not what they created me to do. What Ramirez didcreate me for… was to make this leap; contact; understand… report. Ramirez was the only one who understood the possibility there wouldbe Mospheirans. He thought the people we’d left behind us might have changed; the other captains didn’t think so.” A second sip, steadier. “He’d planned we’d meet a tamer situation, a safe, functioning station; that we’d present you a present: a star station and a starship to reach it, and we’d build another ship; and another; and weave this grand web that gave us all access.” Jase shook his head. “Which the alien attack demolished. We ran home. Here. And when we found what didexist, then the other captains looked at me with my language study as something other than Ramirez’s personal lunacy.”

He knew this part. He sensed Jase was going somewhere new with it. The other captains? Josefa Sabin was the second shift captain in the twenty-four-hour rotation; then Jules Ogun, and the fourth, different than they’d started with, since that man had died last year, was Pratap Tamun.

“But they don’tsee me as having authority,” Jase said.

“Then join our group. We’ll make damned sure they listen to you.”

Jase shook his head. “That would undermine Ramirez. He’s had confidence in me; I’ll back him. Just… don’t push too hard too early. Give me a day or so to sit down with Ramirez, let us put our heads together. If you’ll trust me, I’ll see if I can level with him and get his agreement.”

It posed a question, not Jase’s honesty, but how much three years of rarified diplomatic atmosphere had prepared Jase to stand on his own feet; and how much internal politics of the Pilots’ Guild would listen to reason.

“ Chei’no Ojindaro. Pogari’s Recall.”

Another machimi play. Jason’s gaze flickered first with an effort to remember, then with complete understanding. “ Hari’i,” he murmured, sliding back into Ragi with no apparent realization of it. By no means.

The return of a long-absent retainer to a corrupt house: a recognition of loyalties, a sorting-out of man’chi… a resultant bloody set of calamities.

“You’re sure,” Bren challenged him.

“I have to try.”

“Don’t tell me have to try. You know you can work with me. The issues here aren’t for guesswork.”

“Tamun,” Jase said. “Ogun’s the chief bastard, but that goes with the job. Tamun is our problem, hardnosed, Sabin’s man, or used to be. Those two have split. Ogun’s not a fool. I canexplain a situation he didn’t anticipate to exist. Pratap Tamun’s the problem.”

Straight out of the Council, Bren recalled Jase saying when he knew Tamun was elevated to the captaincy: the captains tended to be more moderate, the Council more inclined to go for a radical solution. And his appointment to what the Guild called the fourth chair meant that one of the captains tended to more volatile solutions.

“They won’t risk relations with the planet,” Jase said further. “It’s not in their interest. There’s every chance of getting what they want if they ask Tabini and ask politely. As I mean to tell them.—Bren, you’ve never asked me what I’ll say; but you know I’ll advise them to deal with Tabini.”

“This is the question I will ask you: will they listen?”

Jase took a deep breath. “The same us-only streak that runs in the Heritage Party is there. There’s a strong party that thinks aliens out there and aliens here are no different, and the way you feel about Kroger… I feel about Tamun. I think he’d rather deal with the Mospheirans. The whole faction might not even know yet that they’d rather deal with the Mospheirans, but I think there’s a chance the Guild will go through that stage—until they get a strong taste of Mospheiran politics to match their first sight of atevi. That’s going to scare them. No matter they’ve seen them on screen. They’re impressive, leaning over you. But you know and I know the Guild has no real choice. Ultimately, Tabini is their best and only answer.”

“He’s going to be another shock to their concept of the universe.”

“They already had a real shock to their concept of the universe when they lost a space station. They’re scared of aliens. They’re scared as hell of losing this base, and of being double-crossed by aliens they don’t understand. Bren, understand their mindset. If we don’t have this station, we don’t have anything—no population, no fuel, no repairs, no place to stand. That’s death. That’s death for us. That’s their position.”

“You and I both know that, for reasons of state, friends lie. But I’mtelling you, and I want you to tell Ramirez. Tabini’s a master of double-cross, but stress this. He’s also fair. He welds parties together; he’s united the Atageini with his own. He’s gained lord Geigi.”

“He deals with his grandmother,” Jase said with a wry smile. “ There’sthe training course.”

“And he deals with Tatiseigi. This is a powerful, progressive influence that’s tripled the size of the Western Association, gained votes in the hasdrawad and the tashrid, and notconducted a bloodbath of his rivals, which is hell and away better than his predecessors. You tell Ramirez this. In this lifetime, you’re not going to get better than the man who peacefully took the Association to the eastern seaboard and simultaneously took atevi from airplanes to orbit. And who has the resources under rapid, efficient development. There is not going to be a better association for Ramirez, human or atevi.”

He didn’t have to convince Jase. It was Jase’s store of arguments he supplied.

“Ramirez will listen,” Jase said. “Your Mospheiran history about the Guild’s misbehavior might be true: I don’t believe all of the accounts, figuring your ancestors as well as mine had their side of the story. The others will argue.—But here’s the hell of it, Bren, and this I’ve realized slowly over the last three years. A ship’s a small place, compared to a world. What you don’t understand, what you can’tunderstand by experience… you think Mospheira’s small and bound by a small set of habits. Phoenixis smaller. Compared to Mospheira, Phoenixis a four-hundred-year-old teacup, same contents, same set of thoughts, whatever comes and goes on the outside, we’re on the inside. On an island two hundred years? We’ve been spacebound in that teacup for four hundred. We have the archive; we have all the culture of old Earth; but all of us on Phoenixhave in that sense been in one same small conversation for centuries. I’ve been thinking about contrasts, the last few days. And this is the big one. All of us on the ship have the same database. We don’t encourage divergences.”

Curious, he hadalways thought of Phoenixas the outgoing group of humanity, the explorers, the discoverers; and Mospheirans as limited.

But twenty-five hundred individuals, only twenty-five hundred…

“How many areon Phoenix?” he asked, that old, variously answered question between them.

“Fifteen hundred” Jase said, a thunderstroke in a deep silence. The fire crackled, reminiscent of Taiben, of Malguri, old, old places on the earth of the atevi, aboriginal places where fire was the means of heat and livelihood, far, far different than this most modern waystop. ”Fifteen hundred.—Understand, when we built the station, out there, before I was born, there were six thousand; the ship was doubled up, full. When the station went, there had to have been nine or ten thousand people, just there. But we’re the core. We sent out all our population to make the other station; and now there’s just… just fifteen hundred humans alive in space, besides the population of Mospheira… thousands, tens of thousands, six millionand more human beings on the planet, on the island. That’s incomprehensible to us. Precious to us. And whatever you think, nobodywants to jeopardize that resource… an irreplaceable one to us. That Yolanda can go up there and talk about millionsof human beings is so incredible to the Guild you can’t imagine.”

He could. Not adequately, perhaps, but he could.

“But in a certain sense,” Jase said, “when you talk to the Guild, you have to imagine a far, far smaller politics. We differ. We do differ. But we have philosophical differences, personal differences; you can’t even call it politics… certainly no regional differences. Generational differences. Experiential differences. Differences of rank: the engineers think one way; the services think another. We respect the captains; we don’t see the same conclusions; but we have to take orders. We always take orders.”

It was the reprise of a dozen conversations, some of it exactly the same; other bits, and beyond the ship-population bombshell, were new, as if, with his ship-home a reality on the horizon, Jase was recalling details. Details not purposely withheld, only lacking a certain reality in Shejidan.

The same, but different, and Bren listened with all that was in him.

“What are you going to do?” he asked Jase. “You don’t take orders.”

“I’m going to tell them things that aren’t in their database. I’m going to ask Yolanda what she said; I’m going to find her and remind her she can say no. I’m going to tell them they’d better deal with Tabini because they won’t have a concept in their universe how to get an agreement out of the atevi without him. But when my gut knows I’m talking to the captains, I’m going to be scared as hell. All the rest of me is going to want to say, ‘yes, sir’ and do what I’m told.”

“But you won’t do that.”

“I can’t do that anymore.”

“You know we’re armed. That was part of the understanding, that we would have our own security when we set up the atevi quarters on station. That there would be weapons, electronics… bare walls and life support; and we tie our electronics in with theirs, all that agreement.”

Jase drew a deep, long breath. “I’ll be damn surprised if it’s there yet. It’s not an emergency yet; it’s what I said. And the rank and file isn’t going to know what to do with it because it violates a dozen rules. You’ll stare at them, and scare them half to hell. There’ll be aliens among them. You know what kind of scare that is, when we’ve already lost one battle?”

“Not looking them in the eyes?”

Jase hadn’t, when he first came. “They really don’t like that. Try to make your staff understand.”

The consequence of growing up in small corridors, narrow passages, managing some sort of privacy in nose-to-nose confinement. They’d discussed that sort of difference over the last three years.

“I rely on you,” Bren said.

“That scares the hell out of me.”

“We share that feeling,” Bren agreed.

“Time for me to go back. It is time.”

At the root of all their plans, Jason had known he had to go back as soon as the shuttle flew reliably—being too valuable a passenger to send up with the tests. He’d known when Mercheson flew successfully; they’d both known… that he’d get the call, eventually.

“We want you back down here to finish the job, if you want to come.”

“I’ll do what I have to do.”

“So will I,” Bren said. “And I’ll work with you. Tabini will. He considers you in his household. That’s an irreplaceable advantage. When they really want to talk to Tabini, they’d be wise to send you to do it.—Might at least work a fishing trip out of it.”

Joke, but a painful one.

“Safer, this trip,” Jase said. “At least.”

“Flinging yourself at a planet?” It was the way Jason had landed, flung himself at the planet in a three-hundred-year-old capsule with two chutes, the first of which had failed.

“Don’t say that.”

He himself didn’t like all he could imagine, either.

Jase hated flying. He didn’t. But at engine switchover, he’d like to have the whole damn bottle of vodka under his belt.

“I promise,” Bren said. “You want a bed here, tonight? It’s late.”

Jase shook his head. “I’m going to take half a sleeping pill. Try to get some rest. If I don’t wake up for the launch, come and get me.”

“I will.”

“You’re not nervous.”

“God, yes, I’m nervous!” He laughed, proof of it, and didn’t think about the engines. “I plan to enjoy it anyway. Experience of a lifetime.”

“An improvement,” Jase said. “Falling out of space on my second parachute… that was an experience.—Horizons. That was an experience. Riding another living creature… that was an experience. Being onwater higher than the highest building… thatwas an experience. I want that fishing trip, Bren.”

They’d been through a great deal. Even standing upright on a convex planet under a convex sky had been a visual, stomach-heaving nightmare for Jason.

Having a natural wind sweep across the land and ruffle his clothing had frightened him: a phenomenon without known limits. The flash of lightning, the crack of thunder, the fall of rain—how could Jason’s internal logic tell the natural limit of such phenomena?

It hadn’t been cowardice. It had been the outraged reaction of a body that didn’t know what to expect next, that didn’t know by experience where unfamiliar stimuli would stop, but that knew there was danger. He was in for the same himself, he was sure, tomorrow.

“Having no up or down” Bren said, his own catalog of terrors.

“There’s up and down. The station spins.—Didn’t when we docked; but it does now. Low doorways, short steps. It’s the household that’s going to have to watch it, and they never have.”

Atevi, in Mospheiran-sized doorways. And furniture. “Well, an experience. That’s what we’re there to negotiate. Cheers.” He knocked back the rest of the glass. Stupid, he said to himself. It wasn’t wise at all, flying tomorrow, before dawn.

“Cheers.” Jase tossed down his ice-melt, and rose.

Chapter 7

A gleam of silver on a black, imposing figure in the dim inner hall, the gold chatoyance of atevi eyes… very familiar eyes, they were, never failing to observe; his staff had been there. He’d been aware of them. Jase had gotten a summons from outside, and now Jase was under observation, however benign. Someone watched, and that someone was Jago, who waited for him. She bade a polite farewell to Jase and, with Jase out the foyer doors, Narani properly attending, she came back to report as he walked toward his bedchamber, two more of the servants waiting in the hall.

“The staff reports baggage is boarded,” she said.

Bindanda, imposing, roundish shadow, said, “The bath, nandi?”

“Very welcome.” He was tired, mentally tired; he wasn’t going to shake the events of the day by lying down and staring at the ceiling. He knew that Jago would oblige him sexually; he didn’t ask that. She had her own agenda, no knowing what, and he didn’t inquire.

Rather he walked on, down a hallway more comfortable to his soul these days than the geometries of the human-area conversation grouping.

Had it only been this morning he’d left Mospheira, and all that was familiar to him from childhood?

Jago walked behind him, catfooted.

“Mogari reports,” Banichi said, also appearing in the corridor. “Nothing untoward, no messages passed concerning Jase, except expectation of his arrival.” Mogari was the site of the dish, the source of communications from the station.

“Good.” He left all such questions to his security, trusting they could manage it far better than he, and would. “Get some sleep, Banichi-ji. If you can leave it to someone else, do. Tano and Algini, too. This all starts very early in the morning.”

“One does recall so,” Banichi said. Banichi had a new set of systems under his hands in the security station, ones Banichi had helped put together, and he knew Banichi had that for a powerful attraction. “Tano and Algini, however, have gone to meet Jasi-ji in his room.”

“To sleep there?” He was astonished. Did they think someone in the Mospheiran mission might have any designs on Jason’s life?

But they were careful; they were atevi, and they were careful.

“For safety,” Banichi amplified the information, “Replacing two of Tabini’s staff.”

“Where are they sleeping?” he wondered, stupid question.

“Nadi, they will hardly sleep. We will survive lack of sleep.”

“Of course,” he said, as Narani, too, entered the central hall, this inner circle of fortunate encounter. A baji-naji inset was above, below, and several places about. No soft green and blue here: definite, entangling black and white and color that fought like dragons in every design.

“Will you have any late supper, nand’ paidhi?”

“No,” he said. “Thank you, Rani-ji, I can’t manage another bite, and I fear I had at least half a glass too much tonight, with Jase.” His head was light. He’d run from supper to late tea with Tabini, to here, all nonstop.

He turned, saw all the staff together, in various doorways all eyes on him.

He’d been afraid, a moment ago, thinking on the morning. In the moment Jase had left he’d mentally expected he’d be alone, like the Mospheirans; but he wasn’t, he wasn’t ever. They wouldn’t let him be. “Nadiin-ji, thank you, thank you very much for coming.”

“A grand adventure,” Narani said, a man who should be, if he were Mospheiran, raising grandchildren… but here was a model of discretion and experience for a lord’s house. “A great adventure, nand’ paidhi.”

“Your names are written,” he said, bowing his head, and meant it from the heart… meant it, too, for the starry-eyed, enthusiastic young woman, Sabiso, who’d come primarily to attend Jago, for the Atageini who had come, rotund Bindanda, who carried the eastern and old-line houses of the Association into this historic venture.

“Nandi.” There were bows from the staff, deep bows, a moment of intimate courtesy before he went into his bedroom, before Bindanda and Kandana attended him there.

He’d used to think of it as an uncomfortable ritual. Now he took comfort in the habit… carefully unfastened the fine, lace-cuffed shirt and shed it, sat down to have his boots removed, all the items of his clothing from cufflinks to stockings accounted for and whisked away to laundry or whatever the solution might be on this most uncommon of evenings. He didn’t inquire what they’d brought and what they’d left or what they might do with the laundry. If he named a thing they’d left, they’d send clear to the Bu-javid to bring it, and God knew it would turn up.

“Good rest, nand’ paidhi,” Narani said, managing to turn down the bed and to bow, quite elegantly and all at once, as young Kandana, a nephew, hovered with a robe. “And will you bathe?”

“Yes, Nadiin.” He accepted the bathrobe Kandana whisked into place, stepped into slippers… should the paidhi-aiji walk barefoot, even ten meters down the hall? The staff would think him ill-used.

It was a very modern bath… porcelain, far newer than the general age of the fixtures in the Bu-javid, but there was absolutely nothing lacking in the quantity of water in the sunken tub. Bren slid into the soft scent of herbs, slid down to his nose and shut his eyes, while the extra half-glass of vodka seethed through his brain, blocking higher channels.

A shadow entered, a dark presence reflected ghostly on dark tiles: Jago, likewise in her bathrobe.

“Shall I bathe later, nandi?”

So meticulous in slipping in and out of the role of bodyguard. Perhaps they were a scandal. He was never sure. He had no idea how Banichi construed matters, and suffered doubts. He wasn’t sure even how Jago construed matters, except that he wasn’t utterly surprised at her turning up now unasked, after this crisis-ridden day.

“Now is very welcome, Jago-ji.”

Smoothly then she shed the robe, tall and black and beautiful as some sea creature… slid into the water and let it roll over her skin with a deep sigh. In the next moment she submerged and surfaced, hair glistening… still pigtailed: with that propriety alone, she could answer a security call naked as she was born, with never a sign of ruffled dignity: she had done so, on occasion, and so had he, and so had his staff. There was no mystery left, but there was admiration for what was beautiful, there was expectation. One didn’t say lovein dealing with atevi, as one didn’t say friendor any of those human words… but bodies knew that despite differences, there was warmth and welcome and comfort. She might technically be on duty; there was a gun with the bathrobe, he was relatively sure.

But she pursued his welfare here, strong, graceful arms keeping him warm, when all at once he felt the chill of too much air-conditioning above the water surface, and the heat of an atevi body beneath. The water steamed in the refrigerated air, made clouds around them, steamed white on Jago’s bare black shoulder, and on her hair.

Large atevi bodies chilled less rapidly than human, absorbed heat and shed it slowly, simply because they werelarger; and tall as she was, she could pick him up and throw him with not an outstanding amount of effort. But that wasn’t in their dealings, which were mutual. The dark blue walls reflected him more than her. She was always warm, and he was chronically cold. Across species lines, across instinctual lines, their first engagement had been a comedy of misplaced knees and elbows; but now they had matters much more smoothly arranged, and had no difficulty in a soap-slippery embrace. Hands wandered, bodies found gentle accommodation under the steaming surface. She enjoyed it; he did. He was recent enough from Mospheira that he was conscious of the alien, and fresh enough from converse with Jase that he still had his human feelings engaged.

And not knowing to this hour whether these interludes with the source of her man’chi were permissible for her or a scandal to her Guild, he still found no personal strength or reason to say no. He found a gentleness in the encounters that never had been with Barb… his weekends with Barb had been more intense, more desperate, less satisfying. He didn’t know which of them had been at fault in that, but he knew that what he and Jago practiced so carefully respected one another in a way he and Barb had never thought about. There was humor; there were pranks; there was never, except accidentally, pain.

He struggled not to let his heart engage. But his heart told him what he and Barb had called a relationship hadn’t been the half of what his heart wanted to feel. He had asked, or tried to ask, whether Banichi and Jago had their own relationship; and Jago had said, in banter, Banichi has his opinions; and Banichi never managed to take him seriously… never quite answering him, either; and it was not a question he could ask Tabini—how do atevi make love.

He was not about to ask the dowager, who—he was sure—would want every salacious detail.

It was sure above all else that Banichi would never betray his partner, that she wouldn’t betray Banichi, not under fire and not in bed.

It was sure between him and Jago that the man’chi involved, the sense of association, flowed upward more than down, and that no human alive understood atevi relationships in the first place—

But the more he involved himself in the atevi world, the more he knew he wasn’t in a pairing. He’d assumed a triangle; and then knew it wasn’t even that, but deep in some atevi design, a baji-naji of their own convoluted creation, and deeper and deeper into feelings he knew he wasn’t wired to feel as atevi felt, not feeling as they did, only as he could.

God help him, he thought at times, but she never asked a thing of him. And they went on as formally and properly in public as they’d always been, always the three of them, she and he and Banichi, and four and five, if one counted Tano and Algini, as it had been from the time Tabini put them together.

He’d been in love in his teens, when he’d gone into the program, with the foreign, the complex, the different.

She certainly was. God, she was… pure self-abandoned trust, and sex, and her exotic, heavily armed version of caring all in the same cocktail.

They rested nestled together till their fingers and toes wrinkled, while the heater kept the water steaming.

They talked about the recent trip to Mospheira…

“Barb came to the airport,” he said.

“Did you approve?” she asked.

“Not in the least,” he said.

They talked about the supper with the dowager.

“Cenedi looked well,” he said.

But she never talked business in their interludes. She had, in whatever form, a better sense of romance than he did, twining a wet lock of his hair about her finger. She’d undone his braid. Her tongue traced the curve of his ear and traveled into it.

A shadow appeared in the doorway, above the steam.

Banichi.

He was appalled. “Jago-ji,” he said; she was aware… surprised, but not astonished.

“Nandi.” Banichi addressed him, incongruously, in the formal mode. “Your mother has called, requesting to be patched through wherever you are. She says it’s an emergency.”

Banichi had been exposed to his mother’s emergencies. He himself certainly had. He was remotely aware of the rest of his body, and simultaneously of the rest of Jago’s body, soft and hard in all the right places, as her arms and her knees unfolded from him.

He probably blushed. He certainly felt warmth.

“I regret the untimely approach,” Banichi said, “but she says she’s calling from the hospital.”

“Oh, damn.” He was on his way out of the water as Banichi procured him his robe.

Jago gathered herself out of the water as he slipped into the robe. He had the presence of mind to glance back at her in regret for the embarrassment, whatever it was, and knew that, in a Situation, Tano and Algini being absent with Jase, Banichi had left the security post rather than send servants into the bath to pull him out.

Bren yanked the sash tight on the robe, on his way out the door. His mother had had her spells before… had had surgery three years ago, one they thought had fixed the problem with her heart as far as age and life choices let anything fix the problem.

At least shewas calling.

God, could anything have happened to Toby or Jill? He had enemies, and some of them had no scruples. He’d cleared Kroger to call the island. Word of the mission could be out, no telling where, and he’d not been in contact with Shawn, to advise him to tighten his mother’s security, that hewas on this mission.

Banichi had reached the security station near the front entry, that place which, with its elaborate electronics, held the phones.

“The ordinary phone, nadi,” Banichi advised him, and Bren turned a swivel chair and settled onto it, picking up the phone that looked like a phone.

Banichi settled into the main post and punched buttons. Bren heard the relays click. “Go ahead,” he heard the atevi operator say in Mosphei’, that deep timbre of voice, and the lighter human voice responding: “Go ahead, now, Ms. Cameron.”

“Mother?”

“Bren?” There was the quavering edge of panic in his mother’s voice, real desperation, and that itself was uncommon: he knew the difference.

“Mother, are you all right? Where’s Toby?”

“I don’t know. I don’t know. Bren, you’ve just got to get back here. Tonight.”

“Mother, I’m sorry. I can’t just—”

“You have to get here!”

“Where’s Toby?” Had there been a plane crash? A car wreck? “Where are you?”

The line spat, one of those damnable static events that happened when the atevi network with its intensive security linked up by radio with the Mospheiran network. He clenched the receiver as if he could hang onto the line.

“… at the hospital!”

“In what city, Mother? Where’s Toby? Can you hear me?”

“I’m in the city!” That meant the capital, in ordinary usage. “I’m at the hospital! Can you hear me? Oh, damnthis line!”

Not inthe hospital. “You’re atthe hospital. Where’s Toby, Mother? Where’s my brother?”

“I don’t know. He got on a plane this afternoon. I think he should be home. I think he and Jill may have stopped at Louise’s to pick up the—”

“Mother, why are you at the hospital?”

“Bren, don’t be like that!”

“I’m not shouting, Mother. Just give me the news. Clearly. Coherently. What’s going on?”

“Barb’s in intensive care.”

“Barb.” Of all star-crossed people. Barb?

“Barb and I went shopping after we left the airport, after we put Toby on the plane, you know. We were at the Valley Center, the new closed mall, you know…”

“I know it. Did she fall?” There were escalators. There was new flooring. The place had opened this spring, huge pale building. Tall, open escalators.

“No, we just came out to go to the car, and this busjust came out of nowhere, Bren.”

“Bus. My God.”

“She went right under it, Bren. I fell down and I looked around as the tires came past and she never said a thing, she just… she just went under it, and packages were all over, I’d bought this new sweater…”

His mother was in shock. She was the world’s worst storyteller, but she wasn’t gathering her essential pieces at all.

“Mother, how bad?”

“It’s bad, Bren. She’s lying there with all these tubes in her. She’s messed up inside. She’s really bad. Bren, she wants you to come.”

He was dripping water onto the counter. His feet and hands were like ice in the air-conditioning. With the side of his finger, he smeared a set of water droplets out of existence, thinking of the new counter, the new facility. He was not at home. He was not going to be anywhere close to home, and he was trying to think what to say. He tried to choose some rational statement. “I know you’re with her, Mother.—Were youhurt?” Setting his mother to the first person singular was the fastest way to get his mother off the track of someone else’s woes. He’d practiced that tactic for years of smaller emergencies.

“She needs you, Bren.”

It was bad.

“Are youhurt, Mother?”

“Just my elbow. I scraped my elbow on the curb. Bren, she’s so bad…”

He winced and swore to himself. His hand was shaking. Jago had turned up in her bathrobe, with Banichi in the little security post, support for him. But he didn’t know who was with his mother, tonight, or how bad the damage was. Shawn’s people watched her. They always kept an eye toward her. But they’d damned well let down this time.

“Have they assessed Barb’s damage?”

“Spleen, liver, lung… right leg, left arm… they’re worried about a head injury.”

“God.” On medical matters his mother very well knew what she was talking about. She made a hobby of ailments. “Has anyone called Paul?”

“That useless piece of—”

“Mother, he’s married to her! Call him!” He tried to assemble useful thoughts and quiet his stomach. His mother was acting as gatekeeper, hadn’tcalled Barb’s husband. He hoped the hospital had.