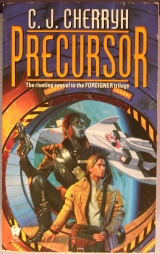

Текст книги "Precursor"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

“It was a curious place,” Banichi said.

“Indeed,” Jago agreed. “But we were able to advise Kate-ji of the situation.”

“I heard laughter.”

“She said she was an endangered fish and again, that we were three amorous old men.”

Bren had to smile, though the vodka had not improved the dry-air headache. He’d tried inhaling water that morning, tried a headache remedy during their stay in the bar, and still felt far too dry, which the vodka he’d consumed had not improved. “Relations with Kroger and Lund are definitely better, though I don’t think we’re communicating much better than you are with Kate Shugart. There’s far too much apprehension around us all, far too much fear of strangers. I don’t know whether the crew is more worried about you or about the Mospheirans. I think they’re beginning to understand they’re not the same as themselves.”

“These humans will not have met even other humans at all,” Jago said. “Jasi-ji was afraid, the first time he saw how large Shejidan is.”

“Jase was afraid of very many things, but he improved quickly,” Tano said from the side. “Is there word of his welfare, Nadiin-ji?”

“Not to our satisfaction,” Bren said. “Always they say he’s with the captains. They claim he has no further relationship with the aiji’s court: they wish to assert command over him, and I’m not willing to have that state of affairs. Nor will the aiji. What did Kate say, Nadiin?”

“That Kroger-nadi was very angry at first,” Banichi said, “and that she’s still angry over the archive, but reconciled, one thinks, and glad to have an agreement which may turn out to her credit. Kate says that all of them are communicating in confidence they’re being observed. One doubts they have that great a skill at it, judging what I’ve heard, but they are attempting to be discreet in their most sensitive policy discussions.”

“The translators believe they’re privy to those?”

“Yes, but with only small occasion to contribute. Kate stated they all like the notion of atevi mining and building; they believe they can interest commercial enterprises in venturing here, but they’re worried about losing all economic initiative in manufacturing to the mainland.”

“The translator was doing very well, then.”

“She makes egregious mistakes,” Jago said, “but goodwill and courtesy are evident in her manner. She is cautious of offense.”

“Despite naming us noble thieves,” Banichi added.

“Forgive her.”

His security was amused. The words for assassin and thief were similar, for the antique word noble and guild even closer. “Perhaps we are noble thieves. Perhaps we might steal our associate from them when we go. Perhaps we will steal all manufacturing.”

“I intend the one. Not the other. Medicines. Electronics. Refining. Food production in orbit. We can stake out interlocked domains. The principles are well-defined, nothing we have to invent.”

“They have not yet opened their defenses,” Banichi said, “and do not trust. One must ask,” Banichi said, “nandi, how far one should go with them, or with Kaplan-nadi either in confidence or in allowing untoward movement.”

Serious question. A very serious question. “Defer to me in this. If I strike anyone, then observe no restraint. But I rather like Kaplan.”

Likewas for salads; it was an old joke with them, but they understood it well enough for one of those transitory attachments humans formed, one subject to whimsy and change by the hour… when for atevi such changes were emotional, associational, life-rending earthquakes.

They might know, at least, how he read the situation. He added, “I rather likeLund and Feldman, too; Shugart is, well, Shugart’s fine. Even Kroger improves with acquaintance. She and I had a bad start, on the flight to the mainland. I rather think she’s Heritage in associations, but too smart for Heritage, too smart to bow to its leaders, too educated in her field, too innately sensible to swallow what they say. I think she’s seen now how things canwork between our species and she’s not going to give the hardliners in her party a report they’ll greatly favor. For political purposes, theywant to regard us as enemies, they want allthe station, and I don’t think she’ll accommodate them. I think she’s honest. I think she sees the Heritage Party as a means to half of what she wants, better than those who’d rather not think about space at all, but I think if she sees a way to get Mospheirans up here without being directly under Guild authority, I think that satisfies most of what she wants.”

“Kroger is aiji in that group,” Jago mused, “one suspects. An aiji indeed, then.”

“I’m still not sure what Lund’s authority is. Possibly he has the same inclinations to leadership. Possibly he’s even Heritage himself and quite canny at it—his department is rife with that party; but he seems far more skilled at getting along with other humans. Kroger is leader, in terms of having her way, and not owing man’chi to those who think they’re her leaders. She has thorns, doesn’t like what’s foreign, but she also has a brain; and I think—I hope—she’s used it in the last several days. I’m coming to respect Kroger, however reluctantly. I hope that lasts.”

“One also hopes it does,” Banichi said.

“Supper tomorrow evening; a meeting next afternoon with Sabin; one hopes we make contact with Jase. Not a bad day’s work.”

“Shall Tano and Algini attend you at supper this evening?” Banichi asked.

“Certainly.” He had no objections to his staff doing turnabout at the luxury of the formal table and food served at the moment of perfection; more, he counted it a chance to brief the junior pair in more detail, and to give Banichi and Jago a break, or conference time, or time for a lengthy, self-indulgent bath … whatever they might want. They’d gone short of sleep in recent days; and whether something of a personal nature ever went on in that partnership he still had no idea, not a clue.

No jealousy, either. He owed them both his life and his sanity.

“One will dress,” Tano said with a bow of his head, and that matter was settled.

Bren himself went to change shirts… how freshly-pressed shirts appeared on schedule was a miracle of the servants’ quarters, but he took them gratefully as they were offered, a small indulgence of rank, and allowed Narani the smugness of small miracles.

He fastened buttons, turned on the computer, gathered messages, in the interval before dinner.

There was a short one from Toby:

Bren, Jill and the kids are gone. I can’t find them.

His hand hit the wall panel, dented it.

“Nadi?” It was Sabiso’s inoffensive voice, concerned. He collected himself, faced the young woman in formal courtesy.

“A difficulty, Sabiso-ji, a small difficulty.”

Her glance surely took in the damaged panel. She lingered. “Shall I call Jago, nandi?”

“No,” he said mildly. “No, no need.” He wanted to put his fist throughthe wall, but a broken hand wouldn’t help the downward spiral of the situation. He didn’t want to alarm Sabiso. He didn’t want to explain the situation to his security.

He was furious with his brother, didn’t even know why he was brought to the irrational brink.

Not rational. Not at all rational. Not professional, damaging the wall panel. Downright stupid, leaving a trace of his temper. It wasn’t like him. Accumulated stress. Short schedules. The frustration of his position.

He walked over to the vanity counter and tried to calm himself with cold water, the single frustrating handful he could get from the damned spring-loaded tap.

Sabiso still lingered, not about to leave a madman. He could hear her small movements. “You may dismiss worry, Sabiso-ji. Please go about your duties.”

“Yes, nandi.” Confronted, she did leave. He gave it a very short time before he might expect Jago.

Whydid he want to throttle his brother? What in hell was it in a perfectly reasonable message from his brother about his own personal distress that made him dent a wall panel?

Simple answer. Toby had just asked him to leave him the hell alone in one message; and he’d agreed, and sent an irrevocable letter to their mother. And now Toby broke Toby’s own new rules and wanted him to worry… for a damned good reason; he could only imagine Toby’s state of mind.

But, dammit, it was part and parcel of the way his family had always worked: first the ultimatum to leave the situation alone; then two hours later a cry for help he couldn’t possibly ignore, and in most cases couldn’t do a thing about but lose sleep.

He couldn’t do a damn thing in this instance about Jill and the kids. He figured, somewhere in his personal psychological cellar, that the last straw in that marriage might have been his call to Toby to come back to the capital, when things between Jill and Toby were already strained. It was his fault. He’d done it.

And they had to quit the cycle they were in. He couldn’tfix Toby’s problem. He couldn’t go on a search for Jill.

He had to take it just as Toby doing what he himself had reserved the right to do: send an advisory. Toby had that right, too. Toby’s wife and kids were missing… in a world where political lunacy had flung rocks at windows, pegged shots at perfect strangers, and had a security guard from the National Security Administration guarding his brother’s kids from a distance.

Where in hell were the guards when Jill took the kids? That was Shawn’s office, at a primary level. Did Shawn know where Jill was, and would he tell Toby?

Dammit, he was up here releasing the archive files to the planet, the world had just found out there were missions going on up here, and Jill picked a damned hard time to do a disappearing act.

He settled down and wrote exactly that, in a far calmer mode. I’m sorry as hell, Toby. It’s all I can say. Likely she’s at the cottage or she’s gone to her family. I’m sure she’s all right. Tell her I said it was my fault and she should be angry at me…

He deleted the last sentence, one more interference in Toby’s household, in favor of: Contact Shawn. Get answers immediately. Don’t assume. This is a safety issue. Pride is nowhere in this. Protect them.

The message was stark, uncomfortably brief. He knew Toby was absolutely right to have told him, dared not reject the possibility it wasmore than anger on Jill’s part.

He was the one who’d brought his family the necessity of security measures, armed guards, all those things. They’d begun to lean on them. SurelyToby had already been to the security people. And they didn’t have answers?

He couldn’t do anything, except fire a message to Shawn, on restricted channels. Toby’s wife and kids are missing. Need to know where they are.

… and knowing that if that inquiry reached Jill and embarrassed her in a marital spat, it might be the true final straw in her marriage.

He’d done all he could. He couldn’t spare personal worry. He couldn’t afford to think on it. He calmly wrote another message for Mogari-nai, this one to relay to Tabini.

We have spent an interesting day touring the station and meeting with various crewmen. We have not yet located our associate, and have assurances the authorities are asking him close questions. I am concerned at this point but find no alternative. Particulars of my negotiations with all parties did attach to my last message. Please confirm that those files reached you, aiji-ma. I remain convinced of a felicitous outcome but find that certain representations are dubious. I was far too sanguine not of the early progress, but of its scope. Relations with the Mospheiran delegates have become smoother and those with the ship-aijiin more doubtful. Also my brother’s family is missing and I hope you will pursue queries with Shawn-nandi, aiji-ma, discreetly. Personal argument preceded the disappearance, but the unsettled times are a worry.

On the other hand, after some inconvenience we have scheduled a meeting with Sabin-captain, and hope that a session of close questions will allay the concerns of the two less available captains and bring us closer to reasonable agreement. We have repeatedly asserted and I still believe, aiji-ma, that future association with the ship-humans is to the good of all parties including the Mospheirans and the only reasonable course for the protection of all living things. I am more than ever of the opinion that the long experience of Mospheirans and atevi in settling differences between our kinds may prove both confusing and alarming to the ship-humans; but that it also offers a surer defense than any weapon of their devising.

He sent. And hoped to God that Shawn readily had Toby’s answer about where Jill and those kids were.

Supper was, for the first time, a vegetable preserve: such things were kabiu, proper, without going against the prohibition against preserved meat. Tano and Algini shared the table with him, and he mentioned nothing of Toby’s difficulty, there being nothing any of his security could do about it. He’d developed a certain knack over the years, of dismissing things on Mospheira to a remote part of his attention, of shifting utterly into the mainland; and now further than that, into complete concentration on his staff, on the problems of Sabin and Kroger, on the regional labor resources, shuttle flight schedules, and station resources. Tano and Algini in fact had been working the day long on the security of the section they now held, on what went on behind the skin of the walls and the floors and arching ceiling, what possibility there was of being spied on, or of spying.

And at the very moment Tano was about to explain the console, the one in their dining hall leaped to life and let out a loud burst of sound.

“God,” Bren said. Tano and Algini were out of their seats. It was not the only source of the sound, and it ceased quickly, as running steps approached the door.

Jago appeared.

“Apologies,” she said. “We have found the main switch, Nadiin, nandi.”

The servants laughed; Tano and Algini laughed, and Bren subsided shakily and with amusement against the back of his chair.

The screen went dark again.

Supper resumed, in its final course, a light fruit custard.

From down the hall it sounded like water running, or a television.

Ultimately, after the custard, he had to send Tano and Algini to find out the cause, and he answered his own curiosity, taking a cup of tea with him.

By now it sounded like bombs.

He walked into the security station.

On one channel, insects pollinated brilliant flowers, unknown to this earth. They were bees, Bren knew from primer school, bees and apple blossoms. On another screen a line of crowned human women dived into a blue pool. On a third, buildings exploded.

The servant staff gathered behind him at the door, amazed and stunned.

Pink flowers gave way to riders in black and white.

“Mecheiti!” Sabiso said, wrong by a meter or so and half a ton.

“Horses,” Bren said. “Banichi, what have we found?”

“One thinks,” Banichi said, “we have discovered the architecture of this archive. There is an organization to it.”

A varied set of images flowed past. He might have delighted in it, on any other evening. He might have laughed.

But while the staff watched, intrigued by human history, he went across the corridor to his room, to the computer, to check his messages via Cl.

Toby hadwritten back. Call off your panic. Jill’s at her mother’s.

Bren sank into a cold plastic chair.

Not… thanks, Bren.

Not… security knew.

Not… I’m going there now.

Not… it’s going to be all right.

The chill sank inward, and lay there. He didn’t move for a moment.

All right, Toby, did Shawn know, did Tabini send something through?

Did I mess things up, Toby?

I want you safe, dammit. It’s not safe there. This is no time for Jill to be running from her security…

He wrote that: Toby, impress on her this is no time…

And wiped it. Jill had left her home, run out on Toby. This was not a woman thinking clearly about her personal safety. Or she was rejecting it.

The news of atevi presence and hispresence on the station was about to break on the island if it hadn’t done so already, touching off every unstable element, from the mainland to Mospheira, in an ultimate paroxysm of paranoia. He was not persona grata with the Heritage Party, which made a fetish of armed preparation for invasion; his mother and Toby’s accidentally stepped in front of a damn bus. If thataccident had stayed out of the news, it would be a wonder, and that report would taint anything he did, as if there was something sinister and personal in the action. Anythingwas substance for the rumor mills, anythingmight touch off the unstable elements who searched the news daily to substantiate their theories, and the theories were no longer funny. It might be announced on the island at any moment that atevi were going to runthe space station; even if the majority of Mospheirans didn’t wantto live under the Guild again, and didn’t want to run the station, they didn’t want to give it up, either.

And Jill picked this moment to ditch her protection.

He couldn’t write plain-spoken things like, The kids are in danger. The Mospheiran link wasn’t secure enough to be utterly frank; he didn’t know whether their mother was on a bus bound for the hospital, whether she’d called a taxi, or even ditched hersecurity. He knew there was danger, knew there were elements that would unhesitatingly strike at the innocent to wound him, and he’d had his try at gathering his family onto the mainland behind Tabini’s much more extensive security. Thathadn’t worked.

He couldn’t protect them. Not any more than he could have prevented the accident.

He bowed his head against his clenched hands, muscles tightened until joints popped. He wanted…

But he couldn’t intervene with Toby, or Jill, or Barb, or his mother.

He couldn’t beg off from his job or ask why in hell human beings couldn’t use good sense. He’d asked that until he knew there was no plain and simple answer.

And he couldn’t blame his brother for being angry with it all. He was angry, too. He could move things in the heavens, shift Tabini’s Opinion and move the mechanisms of the aishidi’taton personal privilege, but he couldn’t do a damn thing to prevent unintended consequences.

Get to her, he wished his brother. Get to Jill. Get her and those kids back under protection. Don’t hesitate. Don’t quarrel. Just do it.

And for God’s sake, write to me when you’re all safe.

Chapter 17

Aiji-ma, we still wait for any confirmation of agreement from the other captains, notably Sabin, third-ranking, who has set a meeting with me for tomorrow station time, whether with her alone or with others of the captains I still have had no word. I have been unable to contact Jase, whom they continually say is in conference with the captains. Nor have I been able to contact Mercheson, nor has the delegation from the island. I find infelicity in the condition of the halls, and their lack of all numbers and designations. Numbers and colors were erased from such facilities in historical times when occupants wished to prevent intruders from knowing their way about. A local guides us whenever we leave, and he receives a map image, I am sure, through an eyepiece and instructions through a hearing device. Neither device is unknown to the island but their use under this circumstance is somewhat troubling, when a small number of painted signs would indicate the route through what is a very confusing set of hallways.

I have received word directly from my brother. His wife is angry with him and has taken up residence with her household, taking the children with her. I have strong security concerns in this move, but will not allow these to override my good sense in the performance of my duties to you, aiji-ma.

Bren re-read the message, searched for words that might cue any other reader as to subject, decided to send as it was, and set up his computer on the table next the wall console.

He punched in. “Good morning, Cl.”

“Hello, sir.”

“Send and receive.”

“Yes, sir”

The squeal went out and came back.

“Good day, Cl. Thank you.”

“Out, sir.”

Cl didn’t readily know about mornings. Bren had a notion to ask Cl what his name was… at least the one that was there of mornings, or this shift, as the ship and station reckoned time.

And breakfast was waiting for him, but he wanted to see first what he had caught in his net this morning. He ached for a message from Toby, but Toby had his mind on other than sending to him, he was sure, and no news meant Toby had gone on his way and likely reached Jill’s mother’s house last night. If something went wrong, thenhe might hear from Toby.

And there was no message from that quarter, none from the island, none from Mogari-nai.

There was a message from Tabini, a simple one: We have been in contact with the Foreign Office regarding matters of your concern. My devoted wife has transmitted a message through your office to your lady mother by the State Department offering her concern and her wish for the lady’s early recovery.

He was astonished. And grateful.

And hoped to God his mother sent a civil reply.

No, no, Shawn would mediate that. It would be decorous.

He had to thank Lady Damiri. And he very much suspected it was a signal. Tabini was aware of everything, and meant to reassure him.

He was moderately embarrassed to have had Tabini do that… though it was not an outrageous proceeding if it were some notable man of the province or of the court: a matter of courtesy, it was. He didn’t know how his brother might receive any word from Tabini. He didn’t trust his family to behave, was what it boiled down to, and he was vaguely ashamed to realize he held that opinion… justified as it might be.

There were messages from various others, more business of the committee heads to whom he had sent messages, he was quite sure, a few outraged ones, who were put out that a human should be leading an atevi delegation and had no shyness in saying so. The traditionalists had their opinions, and in fact he somewhat agreed with them, but couldn’t speak against the aiji’s decision that had put him here. He left them to Ilisidi, and hoped for the best.

There was a message from students of the Astronomer Emeritus, who were astounded and pleased at his voyage, and who asked what wonders of the stars he could see from his vantage.

What celestial wonders? Human obstinacy and suspicion was not the answer the students wanted. The captains, damn them, had sent down images from other stars but had ungraciously declined to give their coordinates or to tell where they were in the human system of reckoning.

He’d arranged the University to transmit its own stellar catalog and its own system of reference and nomenclature three years ago. And Jase had drawn them a map… a hand-drawn, crude thing, but referencing the charts; so the reticence of the Guild on that topic had passed quietly unnoticed, except in certain close circles.

And the students wanted pictures?

In the press of things strange and hostile up here, he’d utterly forgotten there was an outside, that there was a reality of stars and forces more universal than the captains’ will.

He went off to breakfast, thinking the while what he was going to do about those images, putting them at the head of the mental queue, since there was so damned little he could do today about the rest; and then thinking: damn, of course, the archive. Images had gone down to the planet with that.

Locating them in that universe of data meant having an appropriate key. And he had an idea where to find it, knew what the keys ought to be, in words like navigationand dataand starand map, with which his staff might search the download. Simply comparing the two areas of the Mospheiran maps and the maps in the download… simply! There was a bad joke. But it could be done.

“Thought?” Banichi asked him, and, distracted, he had to laugh and explain he was thinking of dictionaries and starcharts.

“Usefully so?” Banichi asked. Banichi had learned that such things as the stellar nature of the sun had some relevance to his job, quite a basic relevance, as it had turned out, but hardly relevant to the performance of it.

“We’re contained and without sight of the stars,” Bren said. “And the students of the Astronomer Emeritus ask me for pictures and data.”

“Are there windows?” Jago asked.

“I imagine that there are, but not necessarily of the sort you might imagine. Most that this station sees, it sees through electronic eyes, through cameras.”

“Interesting,” Banichi said. One wondered why, and, with Banichi involved, came up with several alarming possibilities.

“Of course,” Bren said, “on the other side of all walls and windows and out where the cameras are is hard vacuum.”

“One does recall so,” Banichi said. “But a view of the exterior might be useful. One would like to know the relationship of pieces.”

“That, I might provide. I can ask Cl. There might be a view available.”

“Interesting,” Jago said, too.

They finished breakfast. And after the accustomed compliments to cook and staff—in this case Bindanda—Bren went to the dining area wall panel and punched in Cl.

“Cl,” he said when he had an acknowledgment. “We’ve been here this long and we haven’t seen the stars. Can you show us a view?”

“Not much to see from the cameras,” Cl said. “ But hull view’s active.”

The screen came live on a glare-lit, ablated surface, and absolute shadow.

“Where is that?” Bren asked, having an idea what Banichi was after, and now Tano and Algini had come in haste, Jago having apparently informed them what was toward.

“ That’s looking back over the hull from forward camera 2,” Cl said.

“Is that the shuttle?” Bren said. There was a reflected glow on a smooth surface, the edge of a wing, perhaps.

“ Should be,” Cl said. “ I can angle for a better view. This isn’t the deep dark, here. There’s planetshine, for one thing, not mentioning the star. You want stars, sir, you should be a little farther out.“

It must be a slow morning in the control center, Bren thought, gratified. It was, in fact, the shuttle.

“ Got to close the show,” Cl said. “ I’ll leave you attached to camera 2 on, say, C45.”

“That’s wonderful,” Bren said. “Delighted, Cl. Thank you.”

“Interesting,” Tano said, much as Banichi had said, as Cl punched out.

“More cooperation than we’ve had, Nadiin,” Bren said. “That man is not cautious with us. Others are. Interesting, indeed.”

His security returned questioning looks. “We had early cooperation,” Bren said, “very wide cooperation, and easy agreement with those who were already agreed. I don’t think it attributable to my powers of negotiation, rather to understandings generally made verbal. Now we have these long delays.”

“Dissent,” Jago said.

“And placatory gestures from the servants,” Banichi said.

It did, however atevi the view might be, seem to describe the situation with Cl.

“It’s not safe to press, however,” Bren said. “No more than in an atevi household. The man is a subordinate.”

He settled to work after that small show, imagining that someone thinking more down a human track would have negotiated that camera view much earlier; that very probably Kroger’s team had asked; and that it was something Cl could grant on request, something to amuse the guests and, like the unmarked hallways, to tell them very little.

They were due to meet with Kroger this evening, supposing that came off on schedule. Certainly Bindanda came to question him diffidently about his selections and his menu: “Excellent,” he said, “and one might have a sweet or two. That will please them.”

“Nandi,” Bindanda said, and went off to their galley stores, with Narani in close supervision.

The household ran without effort; it moved and buzzed about him, rarely disturbed him except to renew his supply of tea, while he sat at the small desk and composed letters and replies to various correspondents.

To Toby:

Write when you can. My love and my apologies to Jill and the kids.

There was no letter today. He wasn’t that surprised in the silence.

To his mother, with ulterior motives, both to hear from her and to hear whatever she might have heard about Toby… ifshe had heard a thing from Toby, which she might not have.

Double reason for checking up on her.

I’m doing fine. It’s an interesting place up here.

He struck that beginning. She might take offense at his doing fine in an interesting place; it was somewhat self-centered on his part. He tried again.

I’m just checking to be sure you’re all right. I hope Barb is improving. I want you to take care of yourself, and be assured I’m fine. I hope you’ll keep me posted on everything, and I want you to be sure to get enough rest. I know how you tend to push yourself. I think I inherited it. Do stay to sensible places. You know how certain elements are dangerous when I’m in the news, and I think I am now. I imagine that I am. Know that I love you.

He’d achieved a certain distance in his communication, after sending that other letter, that possibly hurtful letter. He worried about it, worried about it a great deal, and thought now that he’d been too harsh, too self-centered on his own part, to take every move his mother made as self-serving and self-centered. She wasconcerned for him, God knew. She was a mother. She had a son off on a hitherto unreachable space station telling her things were fine while armed security watched over her and everything she did. He’d been desperate; he’d shoved too hard to be free.

What I wrote was honest at the time but one of those things that one starts thinking about; and both your sons love you a great deal. At something over thirty I’ve reached that stage of wanting to be free and to pursue my own course. Kind of late, but there we are. I haven’t taken Toby’s course, home and house and all. And I shoved far too hard when it came to it. Now that I’ve done that I find myself regretting it and wanting to know how you are and to tell you I care. Not to change my mind, but to tell you I care. Both are human, I think.

The I thinkloomed out at him on rereading. In all honesty, it was an I think. He didn’tknow for certain any longer, or hadn’t since his teens, when he’d gone into the University program and begun to separate from the culture he’d been born to.