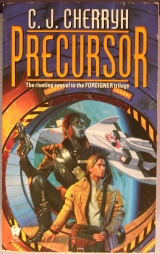

Текст книги "Precursor"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

He didn’t like the shape of it. Clearly, Banichi hadn’t liked it, and had seen in the outage something that might not be an accident.

That hadn’t been an accident, he was now certain. Something that had happened along with some struggle on the station, perhaps even a schism in the crew, or something designed to put the fear in them and justify both Sabin’s reluctance to meet with him—God knew whether she was secretly meeting with Kroger—and the communications problems that cut him off from advice and information from the planet.

He had to work around it. Had to get somethingthrough to advise the planet there was something not right up here.

Mother, he wrote, in language he was very sure station spies could read, I’m sorry to have been out of touch. They’ve been experiencing communications difficulties here. I love you. Be assured of that. I hope things are working out for everyone. I wish I’d brought my camera up here. One thing I do miss beyond all else is pictures of home. You know that one of you in the red suit? I think of that, and the snow, up on Mt. Adams. Sunset and snow. Fire and ice. You

Did you find a cufflink? I think I left it in my room.

I hope Barb is better. Tell her I think of her and wish her a speedy recovery.

Your son, Bren

There was no red suit. His mother never wore that color, swore it was her worst; that was why they had agreed on it as an emergency notice. Red suit: emergency; contact Shawn; watch yourself. It was the only code he had now that might get through the security blackout… if the authorities chose to let him go on receiving small messages, while they knew Tabini’s signature and blacked those out. If they were at all wary, they wouldn’t let it through. If they’d ever noticed Banichi’s trip to the shuttle, they wouldn’t let it through.

Trust me, he wished the captains still in power. Believe me.

God, he hoped no one had spotted Banichi’s move.

“Cl,” he said, “we’d like Kaplan to escort the Mospheiran delegation here, if I can arrange a dinner meeting at 1800 hours.” He held his breath. “Will that be a problem?”

Cl answered somewhat abstractedly, “ Kaplan, sir. Shouldn’t be.”

“I don’t suppose Jase can join us.” It was part of the long-established pattern. He never let it up.

“No, sir, Jase Graham is still committed to meetings.”

“What about Captain Sabin? Any chance of resuming that appointment? We could perfectly well set a place for the captain, if she wishes.”

“ I’ll relay that, sir,” Cl said, and a few minutes later replied, “ The captains are all in meetings, sir. She did relay regrets and asks for the 18 th.”

The day of the shuttle launch, ship-calendar. It was an outright question.

“Tell her I’d be delighted. We’ll arrange a special dinner.”

Sabin wasn’t the only one who could miss an appointment. He had no hesitation in that small lie, and was only minimally tempted to believe Sabin was oblivious to that date.

Was he leaving? Would he be aboard? Sabin very much wanted to know that, in her relayed question.

And dared he tell the truth to Kroger in time to let Kroger get aboard?

Certainly it would not be prudent to tell Kroger everything he knew.

Chapter 20

“I propose to go down to the planet for a few days,” Bren said, over the main course, and after a rambling appetizer conversation that had taken them from skiing on Mt. Adams to the better bars on the north shore. “I’m disappointed in the degree of cooperation we’ve gotten. Either we meet with the captains, or we don’t. I suppose that I’m coming back on the next flight, but I might not. We’ve got to fly that test cargo sooner or later.”

That occasioned raised brows. It was the same arrangement as last time, Kroger and Lund at the formal table, Kaplan and Ben with Tano to keep them distracted, and to get out of them whatever information Tano could obtain.

“You’re breaking off negotiations?” Kroger asked. “Or retiring to consult.”

“Retiring to consult. I fully plan to be back. It’s quite open, as to whether we return on this shuttle rotation or not. I have administrative duties back on the mainland… and a family crisis on the island.” He used that fact shamelessly to convey personal reasons which ought not to make a difference, but which reasonably could. “I think a month’s stand down to let the captains think and analyzemight not be a bad thing.”

Kroger had not quite ceased eating, but the utensils moved more slowly for a moment. “We came prepared to stay longer.”

“My staff will remain here to work. If the cuisine on the station is as bad as I hear, you’re perfectly welcome to dine here while I’m gone. My staff will by no means be sorry to have guests to exercise their talents. And Ben and Kate of course can practice their skills.”

There was a small moment of silence, and the utensils came to a slow stop as Kroger tried to consider the possibilities…

even the chance, perhaps, that the staff might know enough Mosphei’ to be a problem to them.

And the reality, too, it might be, that atevi were here to stay.

“The aiji could waive the cost of a ticket down and back,” Bren said, “if you wished to come down and make your own representations to him.”

“I haven’t that authority,” Kroger said, clearly disturbed. “You have to talk to the State Department for that.”

Interesting choice of words. Very interesting, to an ear attuned to language. The insiders to the various departments tended, though not infallibly, to shorten that down to State… you have to talk to State. You have to talk to Science. It gave Kroger credibility as an outsider, that expression, someone chosen for a mission, but not an insider, not ordinarily a negotiator: a robotics expert, chosen to come up here and see what the state of the machinery or the science might be.

Because thatwould govern how willing human beings might be to undertake the work.

The mind went zipping from point to point in mid-smile. “I will seek someone to do that,” he said. “I think we ought to firm up the agreements we have.”

“Sounds like a good idea,” Lund said. Lund had stopped eating, and paid thorough attention. “I, on the other hand, wouldn’t mind the trip. I’ve been curious about the mainland. And I might have something to say to the aiji, if I can get you to translate.”

Kroger’s brows knit, but she didn’t say a word in objection.

Interestingpower structure in this Mospheiran committee. One could discount Lund, but he wasCommerce, and he did have, Bren suspected off and on, a certain authority in his own realm: trade, commerce, and business representations.

And indeed, it made a certain sense, as he’d set the matter forth to them. It was a good solution to the dilemma of how much to tell the Mospheirans about what could become a dicey situation, particularly for his own delegation.

At least he wouldn’t have failed to advise them he was leaving. He could get his hands on Lund, figure him out within the context of Tabini’s court, get on his good side.

“I’d advise you don’t need to dismantle the mission,” Bren said. “Just pack a bag, clothes, that sort of thing. The aiji can arrange flights to the island if you like, strongly supposing you’ll need to consult while you’re down there. The shuttle goes up again in a month, and you’re guaranteed space.”

“Two days,” Kroger mused, the very short interval for preparation. “I don’t know, Tom.”

“You can always make it a last-minute decision,” Bren said. “Unfortunately the shuttle goes down unloaded. Which is a situation we should fix. It’s terribly expensive to do that.”

“Get some manufacturing going up here,” Tom said. “There’s an archive full of things we could be manufacturing; there are dozens of abandoned facilities up at the core, in microgravity. Medicines, for God’s sake. Metals. Ceramics.”

“First we need to get enough atevi crew up here working to establish these areas as safe,” Bren said. “I plan to bring a few technical people myself on the next trip up.” Not to mention increased security, but a few atevi manufacturing experts, who understood the machines that built the vehicles and stamped and pressed and drilled. Robots. That new word, for a class of machines that had never been perceived to verge on intelligence.

The ones Kroger proposed were far more independent, capable of decision-making, and required, he suspected, more computer science than Science had ever admitted existed.

And it must, by what he suspected. Science hadn’t told State, not at his level, but it must; and now atevi had to become privy to that knowledge as well, in computers, an area where atevi innovations had scared hell out of human planners… the one area of human endeavor besides security technology where atevi had simply taken the information provided, gone off on their own and come back with major new developments.

Humans had become very nervous about atevi and computers.

“Might we arrange the same?” Kroger asked. “Free passage?”

“I think I can arrange a suspension of the charges,” Bren said. “On a one-time basis. This is to the benefit of both.”

“Two days,” Kroger lamented a second time. “Damned short notice.”

“Busy month,” Bren said, “on the ground. But every trip, the shuttle should bring a few people. We can arrange to carry a certain number free of charge, where they’re filling up space.”

“You can do that,” Kroger said.

“At least for the present mission,” Bren said, and took a fork to his dinner, very much relieved to have settled the human mission problem, still asking himself whether he ought to level with Kroger, and finally took the plunge. “We’ve received indications that there might be some disturbance within the local administration. That Ramirez might have a health problem. That the delays might be due to that.”

“Are you serious?” Kroger asked, aghast.

“That’s another reason for our timing in going down right now.” He was very glad to see that she was surprised. “I think they’re trying to sort something out; I don’t think we’re going to get damned much done until they do, and I think it’s a good interval to go consult.”

Clearly Kroger was dismayed. “That puts things in a different light.”

“Not much. A delay.” He chose the light to have on it, a bland one. “Captains will come and go. That matters very little to us. They settle their affairs, we settle ours.”

“How do you knowthis?”

“We have our ways,” he said. “It’s an interpretation of what we see, not an observed fact, but I’d bet on it.”

“You mean you’re guessing.”

“I mean observations lead us to this conclusion,” he said, deliberately obscure. “That’s different from a guess. How much credence you put in it… that’s a matter of judgment, but I take it very seriously, seriously enough that if the captains are taking a great many pains to keep us from finding out, indeed, I’m not going to upset them by telling them what I guess. I’m simply going to take the pressure off them, allow them to solve what is their business, and give myself time to solve some of the other problems that are piling up on my desk at home. I just think this is going to be a hiatus in constructive work, after which we can get back to business.”

It was a fairly complex lie in the center, with truth in the operational sense in that it wasn’t quite a lie, in that it was honestly his best attempt to signal Kroger without spilling everything: excuse me, Ms. Kroger, but we may be in the center of a local war; best keep a low profile… at the very least, don’t stand up and wave for attention.

Certainly she paid him strong attention. She had gray, cold eyes, one of her most disconcerting attributes, and all that concentration was on him.

“Are you saying there’s danger, Bren?”

“There’s danger inherent in our situation, but less if we mind our own business, which one can do simply by staying in one’s quarters and waiting for them to sort it out. I just have too damned much business down on the planet, and there are constructive things I can do by relaying this to the aiji in person. It’s far easier to persuade him, frankly, where there’s give and take and where I don’t have to worry about some faction getting wind of it. Tabini-aiji and I can do more over tea in one hour than in forty pages of reports on his desk. Much as we do here. If you feel uneasy and want to go, I think we can contrive an excuse, but if you’re comfortable with remaining here and dealing with my staff, we could certainly use the on-station presence.”

The ice in the stare melted somewhat, and Kroger rested her chin on a crooked finger. “There’s more to this than you’re saying.”

“I haven’t been able to get hold of Jase Graham since we got here. I’m worried about him and have been, and, frankly, yes, there could be danger of some sort. But if they want anything from the planet and I think they do—they’d be fools to do anything to us. We aren’tmembers of their crew. Jase, unfortunately, is, and I think they’re asking him very close questions about us, or preventing him spilling to us what’s going on inside their power structure. That’s my honest thought on the matter. It’s possible the captain most favorable to us is dead. But we can’t do anything about that. We don’t corner them and they don’t corner us. I don’t say we have to like them or agree with them, but for the mission’s sake we ultimately have to work with them, and to work with them we have to trust them just as far as we’re sure is in their interest. That’s why we don’t mention this to them. They’ve constructed a fiction for us to believe, and it’s our job to take our cues and not bother them, and do our job at the same time in a way that lets us go on working with them.”

“Maintain the fiction.”

“That’s the job. For at least a month, until we get the shuttle up again, at which time we can arrange you to give me a verbal signal, say, a message to Tom, here, that you think it’s profitable for us both to come ahead, or we can work with you in charge up here and us on the ground. The main thing is that we have to maintain our agreement and reduce the number of parties here. There’s too much chance of a divide and conquer move, and if they do it to us, they’ll behave just as long as it takes to get all the advantage they get, then dig in their heels and become a majority with the other half of us. Let’s not let them work that strategy. It’s not in our interest. Not in yours.”

Kroger considered it. The eyes windowed a factory of thoughts. The mouth gave not a thing away.

“Interesting,” she said after a moment.

“He has a point,” Lund said. “We can deal.”

“Good,” he said, feeling as if insects were crawling on every inch of his skin. He’d not put his apprehensions into words before, but laying them out, even in slightly deceptive fashion, focused the threat, even to such an extent that he considered advising Tom to move early, as he was doing, to reach the shuttle.

There were two days in which to make that decision, with Banichi’s help, among others. Protecting their retreat had become a priority, one in which, if he had a regret, it was overwhelming worry for Jase. If he was right, his leaving might actually gain Jase more freedom.

There was certainly nothing else he could do to help him, except gain more power than he had now.

They spoke of details, in the security of the dining room, monitored down to the last tick and wave pattern from next door; they concluded their meal in a quiet exchange of promises and well-wishes and he escorted them to the hall and outside.

Ben and Tano had set up a table there, and Kaplan was seated with them when the door whisked open. Kaplan scrambled up, snatching his helmet and putting it on, very official. God knew what view their monitoring security had with the thing on the table, as it had been angled… or whether anyone was currently watching. It had been in a position to keep watch on the door.

“No need to be stiff-backed, Kaplan.”

“No, sir.” Kaplan had something in his mouth. Had pockets stuffed.

“Enjoy the candy?”

“Very much, sir.”

“I like the orange ones, myself.”

“I haven’t had the orange ones. Just the red.”

“Nadi-ji,” Bren said, turning to Narani, “kindly find this young man a variety of the sweets, including damighindi ones, if you will.”

Of all people on the station, he wanted to keep Kaplan well-disposed, for one thing because they might owe the young man an apology, one of these days; for another, because Kaplan’s was the finger on the trigger, most locally, most likely, and he wanted Kaplan to have just that instant of remorse and regret that would give his own security a chance. Theywould have no remorse, but they wouldn’t kill the young man, either, if there was a chance to avoid it: such were their standing orders.

He’d had time for Banichi’s warning to sink in, with all its implications. He knew to what extent he was valuable, and knew that in the same way he’d resisted coming here, Tabini had dreaded sending him: Tabini had given Banichi and Jago direct orders, and here they were.

He’d told Kroger as much as he dared say. The rest… the rest depended on getting to the shuttle and getting it safely away. The captains had declined to stay abreast of their plans.

They shouldn’t be surprised if those plans shifted around their own, and shifted in a major way.

Narani came back with a brimming double handful, which Kaplan took and stuffed into any pocket that had any room at all. The man blushed with embarrassment, thanked them, and filled every pocket to the top, until cellophane was clearly visible.

“Have to eat a few,” Bren said cheerfully. “Obviously, or you’ll shed them on your way.”

“Yes, sir. Thank you, sir.”

He wondered if Kaplan was sleeping at all on so strong a sugar intake. Jase had found it quite stimulating, in more ways than one, and addictive. Spread them around, he wished Kaplan without saying a word. Let the rest of the crew share.

They had to include a few crates of sweets and fruit juice on the next shuttle flight.

Chapter 21

Another day, and the next, his last day, and not a word from his mother. Not a word from Toby. Cl claimed intermittent troubles, and said that Mogari-nai might have gotten the notion they weren’t transmitting, they’d had so many equipment failures.

“I don’t believe it,” Bren said to Jago. “The message I have from Tabini-aiji is the most bland thing possible. Felicitations, in the plural for a population.”

“It’s faked,” Jago said quietly. “They have text from the aiji’s messages to them.”

“But don’t know one plural from another,” Bren said. “Damned right it’s faked.”

“An indignity,” Jago said.

“Hardly one we can take exception to at the moment.” It was a death sentence, on the planet, inside the aishidi’tat. “One just has to be patient. They have no idea the seriousness of the act. Tolerance, tolerance.”

“One is tolerant,” Jago said, with a grim and determined look. “But where is Jase, Bren-ji? Is this tolerance?”

“Good question,” he said. And then had a horrid thought, considering Banichi’s foray to the shuttle dock. “One I absolutely forbid you to try to solve, Jago-ji. You and Banichi, and Tano, and Algini. You stay here.”

“We take no chances with your safety, Bren-ji,” Jago assured him. “One wishes the paidhi simply pack those very few essentials, and we will go early, without Kaplan-nadi.”

“I ampacked,” he said, “whenever I fold up the computer case and have it in my hand.”

“You will not wish to leave it here, under Tano’s guard.”

“Much as I trust him, I daren’t tempt trouble on him. They might attempt him, if they thought that prize was here; they’re less likely to attack me, no matter how I affront them.”

“Nevertheless,” Jago said, and went to a drawer in his sparsely furnished room and took out a small packet of cloth. She brought it to him, and began to unroll it, and by its size and shape he had a sinking feeling what it was.

“Jago-ji, it’s hardly that great a threat…”

“Nevertheless,” she repeated, and gave him the gun which had followed him, in his baggage, from one place to the other throughout his career with them. “Put this in the computer case.”

“I shall,” he said. “Or have it somewhere about me. I understand completely. I have no wish to endanger you and Banichi by having no defense, but I say again that my rank and their needs are my best defense.”

“Nevertheless,” she said for the third time.

“I agree,” he said, and put it into the case’s outer pocket, hoping the shape didn’t show too much. “There. Trust that I’ll use good sense.” A thought occurred to him. “Trust that I have no more compunction shooting at humans than I do shooting at atevi.”

“Which is to say, far too much compunction,” Jago said. “But we agree with you that we wish a peaceful passage, and a completely uneventful flight.”

“I’ll be missing supper with the captain,” he said.

“Is the paidhi concerned about that?”

“It’s not the same as declining supper with the aiji. She knew when she asked me. She won’t be that surprised. She won’t take it personally, at least. There’s very little personal in it. That’s the problem.”

“In what way is it a problem?” she asked.

“If it were personal, she and I would have been talking before now. But we aren’t, and it isn’t, and I don’t think she plans to keep that appointment any more than the last. It was only a means to ask me if I was going to leave. That she didn’t choose to ask me directly what should have been a plain question indicates something to me about the minds of the captains, that everything, no matter how simple, is complicated and clandestine; that, as Jase told me, no one ever states a plain intention unless it’s an order, and the captains don’t give one another orders.”

“Do they do this setting the course of the ship?”

He laughed. “I don’t think it goes that far.”

“Then one of them can make decisions.”

One had to think about that, one had to think very carefully on that point. If the rumor was so, Ramirez had ceased to be that person.

“Whenever you and Banichi think good,” he said, “I’m ready to leave.”

A presence hovered at the door, in the tail of his eye. He gave it a full look, and saw Narani, with, of all things, the silver message tray from the hall table.

That was the very last thing he had ever thought to see in use. He thought it must be some parting courtesy from the staff, a wish for his safe flight, a promise of their performance of duty.

“ ‘Rani-ji,” he said, summoning him forward, and Narani offered the silver tray.

“From a woman,” Narani said.

From outside? A written message, rolled up, atevi-style?

He opened it with trepidation.

It said, in bad courtly Ragi,

This message risks our lives, but we need your help, we need it extremely despairingly. If hostile person finds us we all die. Your lordship must not trust any of the leaders in charge of the boat. If you can make unlocked your doorway in the night I have attempted to visit, with all trepidations regarding security.

“It’s Jase,” he said, his voice hushed, even in this secure place. “It’s his handwriting.” The written language of court documents challenged even educated atevi, but Jase had rendered a gallant effort. “Not a damned melon in the document.”

Jase had his problems with homonyms. But no one else on the station couldhave written it in just that degree of semi-competency.

“Narani-ji,” he said, handing the document to Jago to read for herself. “Was it Kate?”

“No, nandi,” Narani said. “A woman of years, if I can judge, and very anxious to be away.”

Jase’s mother was on the station. Friends. Cousins. God knew who it had been; their own hall surveillance might give him the image, but in that sense it made no difference who had gotten it to them. The fact was, it wasfrom Jase, and the only scarier knowledge was, if it had been Jase’s mother, shemight be in some danger.

“He intends to try to join us,” Jago said. “Tonight. Is there any means they might forge this document, Bren-ji? Is it at all possible?”

“Not as far as I know. Even a computer… even the most advanced computer… there are the impresses of the pen on the other side, and the paper… the ship hasno paper, Jago-ji. It’s not something they manufacture. Jase when he came had never written on paper, only on a slate. Never used a pen, only a pointed stick of a thing.”

“One recalls so,” Jago said, and added, “Jase did take a notebook with him.”

“You inspected his packing?”

“He had few clothes, things which I know the ship to lack: sweets, a thick notebook, a packet of pens, a bottle of perfume. He went through no personal scan.” Jago looked entirely uncomfortable, rare for her. “This may have been very remiss of us. But no more did we search you, nandi.”

Weapons were in one sense the thing his security noticed most—on the person of an outsider; in another sense, they were so ordinary as to be transparent, if an ally had them in plain sight.

“God,” Bren said quietly, then answered his own question, even considering Jase exercising his dislike of his captains. “No, he wouldn’t. He would not, Jago-ji. Never in the world would he destabilize our situation up here. He can’t have. They keep saying he’s in a meeting.”

“Which you say is a lie.”

“I know it is. But I think they believe he can’t contact us, and that means under their watch or under their control. If he brought something through and they searched his baggage, as he surely knew they might—but he can’t have lived under your guidance for three years and have done something so rash.”

“One would hope at least he would not be caught” Jago said fervently. “He does most clearly have the notebook.”

“And a hellof a sense of timing! God! What do I do with this?”

“What is wise to do, nandi?” Jago asked. “What must be done, for this mission?”

It was surely a Guild question, herGuild’s question: the dispassionate, the thoroughly professional question. What is wise to do?

Fail an appointment with Jase? Leave him vulnerable?

Or interfere in the inner workings of the Pilots’ Guild, which was an endlessly proliferating problem?

It was a problem they were bound to meet, in long years of working with the Pilots’ Guild. Tabini considered Jase his own, now. Hedid. There was no question of support for Jase’s position on their side, no question what he wantedto do.

His arrangements at present didn’t leave a station without representatives from the planet. It wasn’t an inert, changeless situation, rather one in which Jase, if he was somehow involved in Ramirez’ troubles, could become involved, changing everything.

Creating God-knew-what while he was back on the planet, unable to investigate what was happening.

“If he wants off this station, we’re the only ticket,” he said to Jago. “He knows the shuttle’s going. He’s taken the chance and made his break for our side.”

“Man’chi,” Jago said, though she well knew she was dealing with humans who felt it erratically, that overwhelming drive to reach one’s own side, one’s own aiji, in a crisis.

“Something like that,” he said. “But he’s not helpless against it. He knows what he’s asking us to risk. He knows I can’t act for my own welfare, or his, when it jeopardizes the whole damned planet. He can’t ask that. I won’t give that to my own mother, Jago! How can I give it to him?”

“Is he asking that?” Jago asked sensibly, and he had to draw a less panicked breath.

“No. He doesn’t know we’re going, and he doesn’t know we’re going early, but he knows the way you work. He doesn’t even know we can get that door open, but he suspects you can do it. This is not a confident expedition, Jago-ji. He’s desperate. I think he’s completely desperate. But, damn! Damn it all!”

“I should tell Banichi.”

“We should tell Banichi,” he agreed. “We should establish some sort of watch in the corridor. I don’t know what they can spot on their security boards, but I wouldn’t have that door unlocked longer than need be.”

“We know when something moves out there,” Jago said. “Have no fear of that, Bren-ji. But when he comes, we may go to the shuttle in a great hurry. One should be ready.”

One should be ready. One sat ready, waiting, for hours, talking companionably with Tano and Algini, who would be in charge here, with Narani and the others, who would be dealing with Kroger once they left.

They should be moving now. They should have reached the shuttle by now. It was technically night, and past midnight, that less active hour on the station. The computer was packed, he had his coat on, Banichi and Jago had their coats on.

They waited, having brought chairs into the corridor, just outside the security post, so that he could talk simultaneously to Tano and Algini and the staff, and he declined a cup of tea when the hours dragged on. There was a chance of long waits at the other end of their journey tonight, a chance of having to wait out of view, and he wanted not to have his eyes floating while waiting. He had tucked a few of Kaplan’s sweets in his pockets: the slightly sour ones helped relieve a dry mouth, and dry and ice cold was the condition of the air in the core. He had good gloves in his pocket.

And they waited for a visitation.

All at once Tano and Algini paid sharp attention to their boards and passed a signal to Banichi.

Banichi rose; they all rose as Banichi attached a small device above the switch, and opened the door.

Jase was there, Jase in that wretched fishing jacket, Jase pale, sweating and out of breath, and with a hell of a bruise on his cheek.

Bren welcomed him, flung arms about him, making his security very anxious, considering the circumstances, but Jase hugged him hard as Banichi shut the door.

“Where have you been?” Bren asked, first question, at arm’s length and searching a familiar face for answers. “What in hell’s going on?”

“They shot Ramirez. He’s alive. Bren, I need your help!”

The one thing he wanted to avoid was entanglement insidethe Pilots’ Guild. Anything but that.

And Jase delivered it on his doorstep.

“Who hit you?”

“Getting Ramirez away,” Jase said, still out of breath—scared: that was logical, but completely done in, into the bargain. “Been hiding. Had to trust. Had to prevent you going.”

He’d spoken in his own language, had had nothing else to deal in but his childhood language for the last ten days, and probably couldn’t think in Ragi at the moment, but it was important the staff understand all the nuances. “Ragi,” Bren said, in that language. “This is the aiji’s territory. We aren’t giving it up, nadi-ji. You’re safe here.”