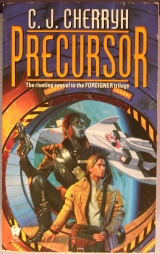

Текст книги "Precursor"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

“Straight to the space center,” Kroger said, looking worried. “Officials of that center.”

“That’s good. That’s the arrangement as it should be,” Bren said. “Probably it did come from the aiji’s office.” He’d disturbed his seatmates, he saw. He wasn’t in the least sorry to have done it. Nobody in the world as it was—or above it—should be as naive as Mospheirans tended to be about anything outside their own politics. “Which means he wants this to happen. What’s your job up there?”

“We aren’t empowered to tell you,” Kroger said.

“You’re empowered to negotiate.”

“With the station.”

“ With the crew of the ship,” Bren said in a low voice. “ Wewere the station, weren’t we, before the Landing?”

Therewas the old hot button, the privileges of the Guild, the lack of basic rights of the colonists, once in-flight emergency put the crew in total charge of the mission… once a ship went far, far off-course and the crew couldn’t get them to any recognizable navigation point, a long, long time ago. The colonists weren’t supposed to land. They had. The Guild had argued for respect of the natives and no landing, and had wanted to stay in space.

They certainly had. There was no Guild craft that could land and no Guild pilot that could fly in atmosphere. All that was lost.

The Guild right now didn’t want to fly in atmosphere. They wanted the station manned, their ship refurbished. They wanted labor, the same as they’d always wanted.

Mospheirans were fit to be that labor… speaking the same language, having the same biology. Mospheirans, however, were of two minds: those whose ancestors had been high-status techs on the station were inclined to be pro-space; those whose ancestors had done the brute-force mining and died in droves were inclined not to.

What do you want?was a loaded question, regarding any delegation of Mospheirans going to talk to the Pilots’ Guild.

“We’re basically fact-finding,” Lund said.

“Find out what they’re up to?”

Kroger shrugged.

“Not hostile to the aiji’s position,” Bren said. “Fact-finding. The big question is… are the aliens real? Did they really find something out there? I’ve worked with Jase Graham very closely for three years… and I believe him.”

They’d reached altitude. He felt the plane level out.

“And does the aiji hold that attitude?” Lund asked.

“Good question. Because I do, he tends to. He pushed for the space program, over some objection, as you may remember. He’s the one who’s enabled this whole program to work. The Guild up there has to understand… do anythingto jeopardize Tabini’s position and there is no shuttle, no program, no resources, no ticket. Alpha Base, gentleman, ladies. Alpha Base all over again.”

Every paidhi-candidate visited that island site, where the clock stood perpetually at 9:18.

Humans floating down to freedom on their petal sails had settled wholeheartedly into atevi culture and offered their technology, blithely crossed associational lines with no idea in the world of the danger they were in. Humans hadn’t… generally couldn’t… learn the language to any great fluency, and because humans had never twigged to the damage they were doing, because atevi themselves hadn’t comprehended completely what the cost of the gifts was… it all had blown up suddenly, and that clock on the island had stopped, precisely at 9:18, on the morning the illusion had gone up in flames.

After that, the aiji who won had settled the human survivors on Mospheira, and appointed the first of the paidhiin, the rare human who could tiptoe through the language.

“We’ve read your paper,” Ben said earnestly.

Yes, they’d read it, and done what they’d done, and gotten permission from the aiji for this flight, nudging the aiji’s precedence for the shuttle he’d built.

Considering Mospheiran history, why was he not amazed at even the linguists had missed the point?

“Well,” he said, seeing there was nowhere to go with the discussion, “well, you’re on your way, and likely it will work. I just ask… in all frankness… that future conversations with the atevi come by channels.”

“I’ll be frank, too,” Lund said, “relying on your discretion… the Secretary of State insists you can be trusted.”

He gave a nod. “In good will, at least. I doreport to the aiji.”

“We aren’t interested in establishing another human government in orbit. They say they’ve found hostile aliens out there. They need work crews to fuel their ship and bring the station back into operation, and if your aiji is willing to supply those crews, and if some humans want to go up there and do it, fine. But does the aiji understand the fatality rate?”

“The aiji does understand that,” Bren said. “I explained it very thoroughly. And neither human nor atevi workers are going to work without protection.”

“And he takes that position. Absolutely.—Or can we say he cares ?”

That, from a Mospheiran of Lund’s background, was a sensitive, intelligent question. “Yes and no. The short version: atevi reproductive and survival sense are wound together in man’chi. It’s a grouping instinct as solid as the mating urge, not gender specific. If a person isn’t in your man’chi, no, you don’t care. If they’re inside your man’chi, you all have the same goal anyway, give or take the generational quarrels. But that’s the average atevi. An aiji has no man’chi upward, and doesn’t give a damn; but he holds together the man’chi of his entire association. If he wastes that devotion, the association will take offense, pull apart, fragment violently, and kill him. They care. Passionately, at gut level, in emotions we don’t feel, the way they don’t feel ours. The aiji doesn’t throw away lives. Biologically, he’s driven to protect them, they have a drive to protect him, everybody cares. Passionately. There’s no chance he’ll tolerate conditions such as our ancestors tolerated. On the question of workers in orbit, you can depend on a united front. Protection, or no workers. He won’t put up with any Guild notion of high-risk operations that don’t benefit the atevi. Second… he’ll constantly be asking what benefit an action is to his association. As will you, I’m well sure, on Mospheira’s behalf. The aiji has everything the Guild’s come to extract from this planet; you have human understanding of how the Guild thinks. It wouldn’t serve either of us to give away the keys to those resources. The atevi halfway understand Mospheirans, as far as they understand any humans. They knowthey don’t understand the Guild.”

“We can’t speak to each other,” Kroger said. “We and the atevi, we and the Pilots’ Guild. We had you to interpret, and you left… pardon me, but left is the word. Then we had Yolanda Mercheson, and shewas called back. We don’t know what this new man represents. We’re rather well without resources. Our mission is to reestablish that understanding.”

“Certainly I agree with that. If you figure out the Guild… tell me. I’ll be interested.”

That raised a small amusement. Small and short.

“What do you think the Guild wants, sending this new man…”

“Cope. Trent Cope.”

“What’s he like?”

Bren shrugged. “Senior to Graham and Mercheson. Probably higher rank. Sicker than seasick, looking at a horizon. Hard to get to know a man when he’s heaving his guts up and drugged half-sensible.”

“I hope it doesn’t work the other way,” Lund said.

He’d opted to travel with Cope, having shepherded Jase through his initiation to planetary phenomena. He’d not known then that Jase would get a recall order; not a clue of it. He hadn’t emotionally reckoned with that hard hit, which he’d only found out about this morning.

He didn’t want to think of it, just wanted to get back to his own apartment in the capital, where he and Jase could have a day… at least a day before the scheduled launch… to sort out what they did think. He was in an informational blackout, trying to get back to deal with Jase… and Tabini-aiji’s orders packed him in with the Mospheiran delegation who was part and parcel of the same crossed signals.

“The atevi report a little nausea,” he said. It was only atevi pilots who’d been in space, testing the shuttle. Docking. There was a scary operation. “I won’t bias you toward it, I hope.”

“I hope not,” Lund said.

Kroger had fallen silent. Thinking, perhaps. Or keeping her own counsel. The two juniors were very quiet.

Then Kroger asked: “What kind of report do you think Yolanda Mercheson’s given?”

Mercheson had fled to the mainland, lived in his household for half a year of her tenure here; but once the government looked stable on Mospheira, she’d gone back. She’d spent most of her time afterward on Mospheira, alone in the culture, miserably unhappy: he knew that. She didn’t love Jase passionately, but they’d made love; they weren’t working partners, but they were friends of a desperate sort, just the only available recourse for a woman otherwise on the ragged edge of tolerating her exile. Mercheson’s early recall to the ship had seemed a solution, not a problem. What she and Jase had had… he wanted no part of, but understood.

That part wasn’t the Mospheirans’ business.

“A fair report,” he said. “She was homesick for the ship. But she bore no ill will to Mospheira, none at all.”

“But she will have given a report to the Guild,” Lund said.

“Definitely. As Jase will of us.”

“A good report?”

“I think so. I think both of them will. There’s no percentage in creating any rift… any negative report, whatever. They’ve sent Cope down, as I trust we’ll get someone for Jase’s spot on the next flight down.” He wasn’t looking forward to it, not at all. Losing Jase still hit him hard… harder than he’d ever anticipated. It might be why he’d reacted as he had to Barb; it might be why he’d gone into this conversation armed and angry. “I don’t have to say this to the two from the FO; but listen to your two advisors. You speak the Guild’s language; but don’t assume that the words mean the same things after two hundred years’ separation. Most of the differences will be stupid, small things; a few could be really significant.” He glanced at Feldman and Shugart. “They know.”

“We trust they know,” Kroger cautioned.

“I know these two,” Bren said. “They’re good.” The blushes were irrelevant to him. He meant what he said. “We’ve only the length of this flight for me to brief you on what we know about the Guild, as I gather the aiji would intend. Expect the aiji to support the agreement between our associations… and to oppose any independent agreements with the Pilots’ Guild. The aiji won’t undermine you. You work with him, I’ll work with you, and that’s far, far better assurance than you’ll ever have out of the Pilots’ Guild, even if they hand you the keys to the starship. We both know the history, better than the aiji does. We know it in the gut.”

“We do,” Kroger said. “And that’s exactly right. A look-see into the workings of the Guild. Anything you know is welcome.”

“I trust Mercheson’s motives; but given the Guild’s history, yes, I’m cautious. They’ll want speed. We want a minimum of funerals. But we do take seriously the fear that sent them running back here. Jase Graham believes it. I’d stake my life on it being true. And if it is, either a band of angry aliens offended by the Guild’s choice of real estate will come here to press their quarrel, or they won’t. And if we equip that ship to fly again… we equip the Guildto deal with the situation that’s going to affect the whole planet for good or for ill. We on the mainland aren’t sure about the goodpart of it. We want to find out what the Guild knows, bottom line, and then apply our own experience to it, for what good that can do. If we have to fight, and if whatever’s out there is that advanced, we’ve got a problem in dealing with the Guild that’s far beyond Mospheira’s old quarrels with them. A very mutual problem. Neither of our species wants to provide labor for fools, and neither of our species wants to take for granted that a Guild war is our war.”

“We’re in agreement on that,” Lund said.

The mood improved. The steward came by and wondered what they would drink with their brunch.

It was small talk then, on recent history, Jase’s two-parachute landing, the aiji’s relations with the island, the building of a second and third shuttle… the governments were no longer at odds, both of them looking anxiously at the sky.

Atevi mutating everything they’d learned about computers and playing games with mathematics… he didn’t mention that—didn’t understand it, for one thing. The ateva who was working on the most abstruse part of it was likely a genius… a mathematical genius, in a species that did math as naturally as they breathed; damned right he didn’t understand it, but he suspected a truth he couldn’t prove, that atevi had sailed right past the University on Mospheira and maybe past anything in the lost library, the one they’d lost in the War… no way to prove it. But the Astronomer Emeritus scribbled away, and wise atevi heads nodded; his students thought him brilliant, and the occasional number counters and philosophical fanatics who traditionally made aijiin nervous had focused their energies on the Astronomer’s ongoing work, too stunned, apparently, or too outclassed to take their sectarian battles onto hischalkboard.

A lovable, slightly otherworldly fellow… there was the devil in the design, sweetly philosophical, thinking away, building a cosmos theory that didn’t battle the traditional atevi philosophies, just lapped away at the sand beneath them.

The two from the Foreign Office, queried by the steward regarding refills, shot over curiously shy glances, as if they feared to open their mouths even to order drinks: advisors in private, no rank. Bren figured that… terrified of the possibilities, because they were the ones who really knew how dangerous the atevi-human interface was… how explosive and how treacherous.

Lund jovially ordered another martini, Kroger the same. The two translators wanted beers, and Bren asked for vodka and fruit juice.

The steward went about his business.

Lund said, when the man was out of hearing in the general roar of the engines, “How long do you figure this new man will stay down here?”

Cope: deposited on atevi soil some four weeks ago, a man tamely landed via the shuttle instead of flung at the planet the way his predecessors had had to come down… a clerical-looking fellow who’d moved by night and avoided the open sky. They’d learned with Jason. He’d been too sick to go on duty for several weeks… lodged in the space center, since atevi security, sensing irregularity and possibly espionage in his refusal to budge to go to the island, had not let him out of the facility. Jase had gone there for meetings; Cope remained sickened by everything, the smells, the irregularity of lights, the flickering of fluorescent.

And now Cope was on Mospheira, his senses being assaulted by an entire new set of sights and smells. He’d been, when Bren left him, lying on his new bed, not daring to venture far from his new, completely enclosed, apartments. How long would he stay?

“I have no idea,” Bren said. “To judge by Jase’s situation, he may not know, himself. Mostly, he was sick for four weeks. Possibly younger systems adjust better. We don’t know.” Jase had said… watch him. Watch him. “I’d be damned careful of his opinion. I said that to Shawn Tyers when I met with him, and I’ll say it to you, since you’re going into direct contact with the Guild. He’s definitely senior to Mercheson and to Graham. He’s very sharp, possibly malingering, very much on his own agenda, probably intends to check up on everything Mercheson reported when she went back up.”

“Alarming.”

“Since Mercheson didn’t lie, I doubt it’s a problem. That’s what I know. He’ll be looking for resources. He’ll be testing whether the island’s resources exist. Observing the geology from space will tell them some things. Not all. Not whether Mospheirans will work with them, either. Now that there’s a space shuttle and safer access, the ship can risk higher-level personnel down on the planetary surface. And that’s exactly what Cope is.” He had a suspicion the elder members of this group might have friends in the old regime and said it anyway: “The Heritage Party is an embarrassment I hope he doesn’t encounter, but he may try to investigate that, too.”

The drinks arrived, a small break, a welcome small confusion in the sorting-out of orders and napkins.

“To your mission,” Bren proposed then, having shot his small dart at the Heritage Party, the pro-spacers who thought humankind had a natural right to everything in sight. “Here’s to tolerance.”

“To the aiji and his court,” Lund said, “and an alliance of purpose.”

Bren sipped his drink, with, at a slight bump, a glance out the window. Billowing cumulus, slate gray in spots. “Ah, spring over the straits. We’re in for a little chop for an hour.”

“Of course,” Kroger said. “They just served the drinks.”

Old joke, old as mankind, in the general goings-on of Mospheiran air travel, most of it in smaller, slower planes. General relaxation. This was, by default, the longest flight any Mospheiran who wasn’t the paidhi had ever made, except a handful of the paidhi’s friends and family; and those generally came with Toby, on the boat, and to the seaside estate. Mospheiran jet service was limited to the island, not flying so high, nor so long between landings.

“So…” Kroger asked, then, “will we meetatevi when we land?”

The interspecies interface was so meticulously ordered, so bound in regulations, it was a real possibility they would not meet atevi. They weren’t to speak to atevi; that was the law. Atevi… well, atevi would do as they thought they could, and thank God one species of the two adored the law… atevi had a very fuzzy, constantly shifting concept of right and wrong, man’chi-guided and solid as a rock if one knew where man’chi lay.

But written orders and nonspeaking attendants would get them from one place to the other… granted the Messengers’ Guild hadn’t run amok and seized power in the four days he’d been gone, granted Jase was still mediating the paidhi’s office, amid his sudden packing…

God, he was going to miss Jase. He’d be alone… he’d been alone, but he’d gotten used to Jase being there…

“I’m reasonably sure there’ll be an official escort,” Bren said, “Don’t expect them to speak Mosphei’. Don’t correct their pronunciation of your names. They’ll pick what they can pronounce.” Ben and Kate knew how their names would turn out. Atevi would likely adjust Ginny to Gin, in uniformity with her companions, for reasons of felicity… which would take an hour in themselves to explain to the uninitiated in number theory. Fortunately and by chance, none of the names carried particularly funny or infelicitous meanings in Ragi. “Bow. Don’t smile. Don’t expect them to.”

“But you converse,” Ben said quietly, as if saying he could fly.

“Practice,” Bren said with irony. Atevi counted items in sets faster than the eye could blink and either took offense or made linguistic accommodations on the fly. “Long practice.” Not counting hours and hours of math, until he breathed it; not counting becoming so sensitive to atevi expectation that he had analyzed what was wrong with Kroger’s lapel-pin the moment they met, and thought as they entered atevi air space about offering the woman a flower to stick in it… but she was going straight to the space center, and the atevi dealing with strangers expected strangeness: it was all right. “Just use the children’s language. Nothing more. They’ll understand.”

“No turning back now,” Kate said, out of a long silence.

Well, there was. There was a chance of landing and riding the plane back to the island, mission forgotten. But diplomats hated like hell to meet an absolute and public rebuke, or to run in terror.

Lunch arrived, in some haste. The plane met increasing chop, on a direct flight into a security window opened by coastal defenses, and it wouldn’t dare deviate in altitude without a great deal of to-ing and fro-ing on the radio. Possibly they were trying that.

The plane hit a pocket. Bren adjusted his glass of ice melt on his way to his lips, waited, then took a sip.

Human crews.

Human crews flew atevi-made planes; atevi still didn’t often land in or take off from the capital of Mospheira. Mospheiran pilots were fiercely jealous of their few long routes, particularly in this day of space shuttles, nationalistically arguing that atevi pilots had a continent to fly in. These days, too, after doing in the aircraft industry, the legislature protected the handful of highly skilled Mospheiran pilots as a major national defense asset.

The human pilots achedfor a shot at the shuttle. He’d heard that. He’d talked to them, saw the hope they had, but that honor Tabini wouldn’t cede to humans, not yet, and for more than national pride. Tabini’s pilots, experienced in long transcontinental flights, were an asset in the negotiations for atevi rights in space, on the station… to the solar system.

Politics, politics, politics. Everything, even that, was politics, depressing thought… it was the one matter in which he meant to make a change in favor of humans if there came a chance. Atevi had taken to the skies, but the same fluidity that they applied to the law they tended to apply to flight rules… hence the very conspicuous insignia and paint job on the aiji’s plane. The flight crew they had was superb. The backup was, too. When they got down into the ranks of the bush pilots, the prospect was less favorable.

“Comfortable seats,” Tom said. “Over all. Chop’s not too bad.”

“Not bad,” Shugart agreed, about the time the plane hit a pocket.

The talk was like that, serious subjects exhausted. The rhythms and sounds of Mosphei’ hit his ears with idle chatter, good-bad, either-or, black-white, infelicitous two without a mitigating gesture.

Mosphei’ was like that. His mind had been like that, before he acculturated.

Fluent, but not instinctive. The spot-on atevi ability to see numerical sets was more than trained into children: it seemed to him atevi numeric perception might be co-equal with color perception, one of those things that just developed in infancy. It might be emotionally linked to recognition of parents, or safety, if atevi infants developed in any way like humans, and after centuries of sharing a planet without real contact, they just didn’t know. Whatever provoked aggression… maybe sexual response—that might be involved with pattern recognition in atevi. If it was sexual in any sense, it might be why, though children perceived the numbers, they were immune from responsibility, and spoke a number-neutral language. Again… no basis in research. His own observations were the leading edge of what humans did know; and atevi themselves hadn’t a clear notion of their linguistic past, by all he knew… archaeology was the province of hobbyists, not a well-defined science. Linguistics was something practiced by counters. Comparative biology was mostly practiced on the current paidhi, when an atevi physician had to patch him back together… and comparative psychology was what he and his bodyguard did on late winter evenings. He could only imagine what atevi did see, or what disagreeable visceral reaction certain nasty patterns evoked, as atevi had to imagine for themselves that humans somehow saw comfortable felicity and stability in pairs and twos…

Twos in marriage; twos in yes-no; twos in left hand and right hand.

The shuttle had had two hatches when they acquired the design. Atevi had changed very few things in the design they’d been handed, and the mathematicians had gone over it and over it trying to justify two hatches, even come to him in agonized inquiry whether he understood the logic of it… he didn’t. And with trepidations on all sides, there’d been a third hatch, with resultant structural changes. There had to be one exit, or three.

And, God, the other questions they’d come asking… the changes in materials science over the last three years…

He himself—with wise and capable advisors—had had to pass on how much of that technology ought to go sliding off into the general economy. Was it wise to turn industry immediately to ceramics, bypassing much of the development of exotic plastics? What were the economic costs, environmental costs, social costs… costs to tradition and stability, and dared they put a road through to a mine in one subassociation without granting a benefit to another?

Shejidan manufactured certain things. What did it do to the balance of power within the Western Association when Shejidan developed another, and unique, industry?

What did it mean emotionally to the relationship among atevi associations when that shuttle lifted from the runway at Shejidan, heart of the Ragi association, the aishidi’tat?

The decisions were all made, now… an incredible three short years after the shuttle began to take shape and form. Whatever mistakes he had made or avoided, atevi were in space now. The shuttle had made its first flight six months ago, proving the vessel, a disappointment to the aiji’s enemies, vindication for the aiji’s program of technological advancement.

The world hadn’t blown up. There hadn’t been a war. It had been a close call, on that one… but the Heritage Party on Mospheira had been turned back in the elections, the new administration had passed the last election with knowledgeable people still in office, still with public approval. There were still stupid moves, one of the most egregious in recent memory being the message that had launched this half-thought delegation and destined them for space before there was any atevi mission… but he would get to the bottom of it, quickly so, once he landed. He trusted he could smooth over whatever was going on. If it wasTabini’s retaliation against Jase’s recall, he understood it.

If Tabini was mad as hell and if some misdirected request from the Mospheiran State Department had brought this about, Shawn Tyers would owe him for straightening this out. But he rather inclined to the former theory: they want humans… let’s give them humans.

Let them ask again, what they will, and let us see where they temper their demands.

It was, certainly, a way of probing the other side’s intention. It was damned, bullheaded atevi mindset.

And it certainly wasn’t out of line with the way Tabini had dealt with his own species.

To be first at something… wasn’t in and of itself either good or felicitous in the numbers.

He thought about that point, idly conversing with his fellow passengers while the plane crossed the coast, maneuvering through bumpy skies and a rainstorm.

As they descended through the cloud base, he pointed out places of interest in the countryside, a river, a small town, and had an appreciative audience.

They were taking a fairly direct approach, not being routed to the south, as sometimes happened.

And within a shorter time than usual they were over Shejidan.

They’d cut three quarters of an hour off the usual time. By the time the plane was maneuvering for a landing, runnels of rain were tracking back over the windows, roofs occasionally appearing out of the gray.

“We’re awfully low,” Ben announced, peering downward, and then a sharp bank gave them a view down into the hillside residence-circles that, with their connecting walks, served somewhat as neighborhoods and streets.

The leveling of the wings gave them a grand view of the Bu-javid, the hill palace rising above the tiled, rain-grayed roofs of the common neighborhoods… footed with a pink neon glow in the general fading of the light.

“Is that the Bu-javid?” Kate asked.

“Yes,” Bren replied. “That’s the aiji’s residence, centermost.” So was his, but his wasn’t a tourist attraction, not, at least, to Mospheirans.

“Hotels below?” Ben asked, peering down.

The palace was a vast sprawl of a building with interior gardens and pools, skirted, these days, by a proliferation of businesses at the foot of the hill.

“Hotels. Neon lights and hotels.” It wasn’t his favorite change.

“Petitioners to the aiji,” Kroger said.

“That’s right.” Over changes atevi themselves chose, the paidhi had no veto, and Tabini hadn’t stopped it, though conservative atevi complained. Three years had seen a neon growth all through the city. The atevi thought it curious. It looked like downtown in the capital of Mospheira, and it afflicted his soul. “Anyone has the right to see the aiji, if he comes here, and the aiji will see he can come here, if he can’t afford it.”

The plane’s next bank brought a view of other neighborhoods past the window now, tiled roofs in varying shades of red. “There’s your ashiipattern,” he said for Ben and Kate. “See the geometry laid out. The unified walkways. Associations. Apparent to the eye once you know you’re not looking at our kind of boundaries. That’s what the first settlers ran afoul of. Never saw it.”

“Not a straight street in the place.”

“People walk a great deal more.”

“Well, thank God it won’t be for us to figure out.” Ginny’s face, a thin face with a multitude of faint freckles, caught the white light of the window as she looked out on the foreignness of an atevi city. “We’ve got enough problems.”

She hadn’t said a thing in a quarter hour. At this precise moment—maybe it was his imagination—she looked scared as hell.

The plane leveled out.

Stewards wordlessly collected the glasses, and they stayed belted in while the familiar signs glided past the window. They were on final approach to the airport.

“Can we see the shuttle from here?” Kate asked, craning forward.

“Not on this approach,” Bren said, and drew a deep breath, hoping he might find a stable, peaceful city… hoping his security would meet him. Hoping nothing had blown up… besides Jase’s unexpected orders.

He’d gotten far too used to company… psychological weak spot, he told himself. Shouldn’t have done it… shouldn’t have associations he couldn’t keep up. Gotten himself attached to someone he damned well knew would leave.

Unwise, in a man who’d made the professional choices he’d made.

Wheels touched down, squealed on wet pavement. The airport buildings rushed past, went slower.