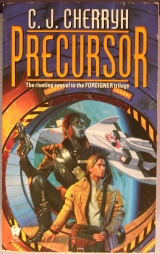

Текст книги "Precursor"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

“They also have talents, captain, as I’m sure Jase hastold you, which enabled the shuttle out there.”

“Human-designed,” Ogun scoffed.

“More convenient,” Bren said. Ramirez, if he was senior, said nothing, and tempting as it was to come back with wit, Bren restrained it in favor of a calm, respectful demeanor. They were autocrats, no question. This wasthe heart of the Guild. “You wield absolute authority here. The aiji has the same. The aishidi’tat, the Western Association, is a misnomer: the aiji rules the whole of the continent, can manage the industry you need, with minimal difficulty, and will keep his agreements.”

“And push,” Ramirez said, “like hell.”

“He’s an impatient man.”

“ Man,” Ramirez said.

“You arein communication with an alien authority, captain. Man isthe term they use for you and themselves, which is fortunate. Their customs aren’t yours. Their instincts aren’t yours. The first contact of humans with atevi was a success that led to a disaster. If you’d come a century ago, I don’t want to guess what might have happened. No supplies. No help at all from the planet. But very fortunately, now there’s a small association of trained personnel who know how to work with one another, a handful of leaders on the mainland and on the island who understand how to avoid problems, and with a good deal of luck we’ll agree, and make you very happy.”

“Not by throwing schedules to the winds and pressing us!”

There it was, natural consequence of the situation, and it was a case of tiptoeing past it or confronting it, keeping the aiji’s position his own secret, or laying it on the table and playing the pieces where they fell.

He made his choice.

“Being one of that small association of trained personnel,” Bren said, arms on the table, “I would have urged the aiji to proceed differently. Unfortunately, no one on your side asked me or Jase about recalling the paidhiin. That looked like a fast move. It touched off the island, it touched off the atevi, and that was exactly what happened. Jase couldn’t explain why he was recalled. Yolanda Mercheson hadn’t called back with reasons. You may have had good reasons, but I couldn’t tell the aiji I understood, and the aiji decided to find out, by honoring his agreement with the Mospheirans and sending one of their delegations up with his and not announcing the fact beforehand, even to me, since I happened to be on the island and not within secure communication range. That, gentlemen, is a very good example of the communications difficulty we hope to avoid in the future. Fortunately, this misunderstanding didn’t harm anyone. I might have argued with the aiji not to do it; but it was already fairly well in progress. My instincts said not to; I came here on twelve hours’ notice because, frankly, I want to know who I’m dealing with before I advise the aiji what to do.”

There was a small, stone-faced silence.

“Mr. Cameron, you’re pushing us.”

“No, Captain Ramirez, I’m being completely honest. I stand between, admittedly, not a foreign power, but an alien one, and you. The Mospheirans will have promised you the sun on a platter. We in the aishidi’tat know their virtues… and their limits. I, as a one-time representative of the Mospheiran government, know their limits; and I say in all desire to have Mospheira benefit from your protection, that I hope you don’t rely heavily on any offers from the island, because I know who makes them. Fortunately, that’s not relevant. The resources critical to your needs are on the atevi side of the straits, except for a little tin and a little silver, which I’m sure Mospheira will be glad to sell you. That’s my opening position.” He drew a breath, seeing he was already pressing most of the way to the wall. He went the rest of it. “The specifics of my position are actually quite generous, unless you have personnel to spare to run a space station, as I know you don’t. This is the atevi’s star, the atevi’s planet, the atevi’s native solar system; you have a ship that looks to have had hard times, and you want supply. Wethink we can arrange a bargain.”

“You’re insane.”

“No. By all you say about an oncoming threat, we and you don’t have two hundred years to learn one another and fight a mistaken war over trivialities. Ask the Mospheirans what they think of sharing the station. They won’t like the idea at all; but they may not refuse it. Atevi don’t want to share it, either; but they know Jase, they think he’s been telling the truth, and they’re disposed to work with you and with the Mospheirans to gain their own say. It’s a situation they know they have to live with.”

“You mind my conveying this to them?” Ramirez asked, sitting in a similar attitude, arms on the table. Ogun frowned, no different than his other frowns.

“I’d be happier with free access to the Mospheiran delegation, but I don’t think you want us to have that, as much chance as we’ve had to do it beforehand.”

Ramirez cast a glance aside at Ogun.

“What do you want in exchange,” Ogun asked, “to arrange this delivery of goods? What coin are we going to trade in?”

“Ideas, captain. Atevi understand that commerce. Knowledge. The agreement that they’ll run this station.” It wasn’t the end of the agreement; there was the question about whose law was going to prevail, but the first objective was possession of the station. “Tabini-aiji declared the terms he wants; I’ve relayed them. I’ve relayed to him what I know about the kind and amount of supply Phoenixhas used; I think he can do it.”

“Can he build another starship?”

That stopped him cold, for at least a handful of heartbeats. It was the logical extension of the request. It was completely reasonable, in that sense.

“I can relay that request.”

“Can he do it?”

“Yes. I think he can. How many are on the ship? How many does it take?”

“Jase didn’t tell you?” Ramirez asked.

“I ask the senior captain, who probably has figured the size of the request he’s making of the planet: how many does it take?”

“Up here? To man the station and handle the equipment? Five hundred minimum. To build… varies. Several hundred at mining; several hundred at refining; several hundred at fabrication…”

“The old figure, the first figure, was three thousand.”

“Twice that. Twice that.”

“Five shuttle trips to start.”

“Mr. Cameron, this station is holed in a dozen places.”

“That’s not as difficult as not having a station, is it?”

“Why was there a war?” Ogun asked. “The Mospheirans say the atevi are inclined to war.”

Bren shook his head. “The War happened because humans moved in with atevi, allied with the wrong party in a chaotic situation, ignored their boundaries, and didn’t know what they were doing. Atevi didn’t see it coming, either. That’s why we have paidhiin. That’s why only one human after the dust settled was licensed to live on the mainland and mediate trade.”

“You turned on your own leaders.”

“Mospheira still pays me. I’ve objected. They keep putting money in my account, and I just don’t spend it. It’s their position I still somewhat work for them, despite my advisements to the contrary, and the plain fact is that I do mediate. They don’t want a war; the aiji doesn’t. None of us want your war, but if it comes here, we don’t see any chance of ignoring it.”

“Do they understand?” Ogun asked, shifting a glance to Banichi and Jago.

“Perhaps some,” Bren said.

“The solar system, is it? Do you have any concept?”

“I can tell you that if unwary humans thread themselves among the atevi, or ignore atevi presence on the planet, there might be another war. Territorial integrity is an imperative, a biological imperative with atevi. Living with atevi is simple. Living among them is difficult, impossiblefor humans who can’t understand that imperative is gut-level, emotional, life and death. If you work with atevi, the interface will be limited, regulated, and very narrow, exactly as it is on the planet, the same people, the aiji and the President of Mospheira, will control that interface; but the goods you want will arrive and youwill never notice the inconvenience.”

Ramirez gave a strange half laugh and shoved back from the table. “I’ve dealt with you for three years, and you’ve been a pain in the ass.”

“I tell you the truth.”

“Your own security,” Ramirez said, with a look up and at the end of the room. “Banichi and Jago?”

“Nadiin,” Bren said, without quite taking his eyes off Ramirez and Ogun. “The captain inquires whether he knows you.”

“We are the paidhiin’s security,” Banichi said.

“Assassin’s Guild.”

“Yes, Ramirez-nandi.” Banichi was very polite in his salutation.

“He calls you Lord Ramirez,” Bren said, and saw Ramirez take that in with mild embarrassment, in the Pilot’s Guild’s long pretense of democracy. Bren added: “Banichi and his partner aren’t security as your Guild defines it. They also have the aiji’s ear, and rank very high in their Guild.”

“Would they care to sit?”

“It’s not their tradition. But they will report, to those places where they report. You always have to assume their Guild knows what’s going on. It has to. They’re the lawyers.”

“With guns.”

“That custom limits lawsuits,” Bren said.

“And this Guild enforces the aiji’s law?”

“The aiji himself enforces the aiji’s law by hiring certain of this Guild; but likewise his opponents may do the same. But the law theyenforce, the law as the Assassins’ Guild sees right and wrong, has no codification, only tradition: that rule of theirs is the one constant, sir, in the whole flexible network of man’chi.”

“Man’chi: loyalty.”

“Don’t fall into the trap of defining their words in human terms. Man’chi: an ateva’s strong instinct to attach to an authority. As long as man’chi holds the organizational structure steady, there’ll be more smoke than fire in any dispute, and you negotiate with the head of the association. Man’chi transcends generations, settles disputes, brings atevi to talk, not fight. The War of the Landing happened because humans insisted on making associations in one man’chi and turning around and making them in another. We call that peacemaking; to them it was creating war. I can’t emphasize enough how dangerous that is.”

“So we don’t agree with them?”

“Agree with their leader. Not leaders. Leader. What we bring to this association, sir, is more than resources and engineering. There’s an expertise to contacting foreigners and finding out their intentions, one that might well have saved your outlying station. It’s the most important resource we have in this solar system, one you have now, in Jase Graham, in Yolanda Mercheson. There’s also an art to listening to your interpreters and not letting politics or your own needs reinterpret what they’re telling you. The Mospheirans have something you need: companionship, a nation, a place to belong; the atevi have something else you need: mineral resources, industrial resources, mathematics, engineering, a highly efficient organization, but more than all of that: adaptive adjustment to a species you don’t instinctively understand. You could stand on the ancestral plains in front of a lion, sir—I believe we both agree what a lion is—and you’d biologically understand what it might do. I submit to you that you can’t ask the lion, but that you’d more or less recognize a hungry one and one that wasn’t. With the atevi, with any species that didn’t evolve in earth’s ecosystem, all those signals, all those assumptions don’t reliably work. We’ll teach you what we’ve learned on this world. That, gentlemen, in your situation, is the most valuable thing.”

“You think we could talkto a species that blew hell out of our station and that probably got our records.”

“I think that if you’re dealing with a species which might be numerous, sophisticated, and very different, coming from a place we don’t know, the ability to figure them out and to talk, if it’s appropriate, might save us. I don’t say you have to like them. I’m saying you need to know whythey shot at you.”

He left a long silence.

“And your atevi can figure that out.”

“No, sir, though they might, now; I’m saying an atevi-human interface might manage to make smarter moves. As a set, we may figure out what we otherwise couldn’t.”

“Makes no sense,” Ogun said. “Confusion’s confusion.”

“No, sir. You aren’t responsible for understanding the atevi; your gut never will do that. Just learn what you should and shouldn’t do. I happen to likethem, but I can’t translate that word and they don’t understand. They’ve given me their man’chi, passionately so, and I can’t figure that from the gut, either, except it’s a feeling like homeand mine, and I know the quality of these two honorable people. You’re not in familiar territory here. Confusedis a condition of life on the interface, but you canknow when you’re with people you can trust. Trust intersects directly with We’re confused, sir, and I know for people who deal in exactitude on both sides, trust comes hard. But trusting the rightpeople is absolutely essential here, or we take on additional enemies when we might have had allies.”

He watched physiological reactions across the table, body language, two men who’d unconsciously leaned back from him leaned forward; Ogun had just heaved a long, deep, meditative breath—thinking, getting rid of an adrenaline rush that probably urged Ogun to attack him, his ideas, and the whole situation that pinned Phoenixto an agreement the Pilots’ Guild had hoped would be very different.

“Think of the planet,” Bren said softly, “as a very large space station with a two-species cooperation that already works.”

“Yes,” Ramirez said wryly, “but docking with it is hell.”

Bren laughed, and immediately there was less tension in the room, less critical thought, too.

“There’s no need,” Bren said. “We do that. You do the technical operations your crew knows how to do, and you teach where we don’t know. You have our cooperation, and with us, the deal’s done, if you agree. Technicalities have to be worked out with Mospheiran authorities, with your various sections…”

“The Guild itself has to meet,” Ramirez said. “You will have a majority on the Council.”

Bren replayed that, replayed it twice for good measure, asking himself if it was really over, if he’d actually done it. He saw a more relaxed body language on the part of Ramirez and Ogun, consciously projected consideration and solemn thought on his own part, and nodded.

“Then we can proceed to numbers, and matters the aiji will govern. The fact that he will have to assure fair, decent supervision of labor is entirely his problem. The aiji will deal with station repairs, the training, labor management, and his own relations with Mospheira. The aiji proposes the area of the station where you have your headquarters and your offices be under your law and your regulation, the same with your ship, in which he has no interest. He proposes that an area of the station of sufficient size be under Mospheiran law, for their deputies and business interests. And he further proposes that the aishidi’tat will govern the entire rest of the station and its general operations under its own law and customs, build to its own scale, and provide your ship with its reasonable requirements of fuel and supply at no charge.” He said nothing of ownership of the station, of policymaking, of war-making, and command of that effort. That all waited on the growth of atevi presence in space, but he also had a very clear idea that Tabini had not an intention in the world of allowing the Pilots’ Guild to dictate to him, once he owned the establishment that fed Phoenix. If the Guild should study the history of the aishidi’tat, it might learn how Tabini had ended up running the continent and, to a certain extent, Mospheira… in the sense that Mospheira nowadays didn’t work against Tabini. But he hoped they wouldn’t concern themselves with old history, not until or unless it repeated itself. Given the history of the Guild, including bringing them a war, he had every determination to see the whole station under Tabini’s guidance. They could shoot him if not… and various interests had tried.

Ramirez and Ogun listened intently, unmoving, perhaps not unaware that Tabini had steered the situation to this point, and meant to go on steering it… perhaps as disinterested in running this station as Tabini was in running their ship or ruling humans.

“We may have an agreement,” Ramirez said. “You will need to present the case to the Guild in general session, but I think you see very clearly what our interests are.”

“I think our interests are entirely compatible.”

“You have to explain it to Mospheira.”

“I have no difficulty explaining it to Mospheira. Ms. Kroger and I seem to have a problem, possibly of my making, but President Durant and Secretary of State Tyers and I do communicate quite well.”

Ramirez gave a small, short laugh, indicative, perhaps, of chagrin at the rapidity of the negotiation.

“Interesting to meet you in person, Mr. Cameron. Jase is quite emphatic we shouldn’t deal with the Mospheirans. Yolanda, interestingly, just says believe you.”

He hadn’t expected that. He gave a slight, tributary nod of the head. “My compliments to Ms. Mercheson. I’m flattered.”

“Jase says you’re the best asset we have.”

“Jase roomed with me for three years. If he and I, given our starting point, haven’t killed one another, peace is possible between our parts of the human race.”

A slight smile from Ogun. There was an achievement.

“Jase has seen what you wanted him to see,” Ogun said.

“Jase could go anywhere he applied to go. He was rather inundated with the workload that descended on both of us. Your shuttle flies, gentlemen. We, on the other hand, worked a very large staff very long hours.”

“The shuttle is a damn miracle,” Ramirez said. “Another Phoenixis far, far harder. Fabrication in space. Extrusion construction. Simultaneously repairing the station.”

“The population of the continent is a classified matter, but suffice it to say, if that is a national priority, labor is no problem. Leave that matter to the aiji.”

“How many fatalities are you prepared to absorb?” Ogun asked.

“None,” Bren said flatly. “But that’s the aiji’s problem. Accidents are possible. Carelessness won’t be tolerated.”

“And meet the schedule?” Ogun asked. “Three years for a starship?”

“Depends on your design, on materials. Transmit it to Mogari-nai with my order, and translation on the design starts today. Materials inquiry starts on the same schedule. We have a good many of the simple conversions automated in the translation, with crosscheck programs; we’ve gotten quite quick at this. We build the ship, we turn it over to you, werun the station our own way.”

“You don’t understand. It has to be built in orbit.”

“Yes, Captain, I do understand. That’s why we have to make immediate provision to get the other shuttle in operation and to get crew housed reliably and comfortably. We’ll rely on you, I hope, to determine what materials are available most economically in space, with what labor force, and what we have to lift.”

“Are you remotely aware of the cost involved?”

Bren shrugged. “There is no cost so long as the push to do it is even and sustains itself. Materials are materials. You won’t deplete a solar system; you won’t pollute a planet; you won’t push atevi any faster than they choose to work. The critical matter is who’s asking them to work, whether their quarters are adequate… and all I say about the second ship is subject to the aiji’s agreement that it should be undertaken as an emergency matter.—Does your ship work?”

That question startled them.

“She works,” Ramirez said.

“That’s a relief.”

“Fuel,” Ramirez said. “That’s a necessity.”

“Can be done.”

“You talk to the general meeting, Mr. Cameron, and we have a bargain.”

“No problem that I see. We’ll straighten out the details, and I’ll go down again.” He added, as if it were ordinary business, not looking up at the instant. “I could use Jase. He can come and go, but I need him, urgently; he’s the other half of our translation team for technical operations.”

“He said so,” Ramirez said with some humor, and didn’t quite answer his request, but the response sounded encouraging to Bren’s ears.

“When, for this meeting?” Bren asked.

“Two days,” Ramirez said. “Oh-eight-hundred.”

Ramirez said a majority was a given, and wanted two days. Bren didn’t raise an eyebrow, but thought the thought, nonetheless, and gave a small, second shrug as he drew out a common notepad with a pen, and made a note.

“Meanwhile,” Bren said, so doing, “we’d like to feel free to move about.”

“Mr. Cameron,” Ogun said, “there’s hard vacuum on the other side of certain doorways, and we don’t allow our own personnel to wander about.”

“Access to crew areas. Guides, if you like. Integration into your communications.”

“Not until there’s agreement,” Ogun said.

“We need radio contact with our own government. As, I’m sure, Mospheirans will ask the same. Resolution of outstanding points on the agenda the last several years, release of historic records, archived files…”

“Classified,” Ogun said.

Now Bren did lift the eyebrow, and stared straight at the captains. “Centuries-old records, gentlemen?”

“Mospheira wants them. There’s ongoing negotiation on the matter.”

“It’s been ongoing for three years. We see no reason for these files to be withheld. Was there any secret in the original mission? Were we targetedto the white star? Or here? That isone of the conspiracy theories, generally promulgated in small handbills throughout the island… has been, I think, for over a hundred years. Of course, that flies in the face of the competing theory that atevi, having just made the steam engine practical, secretly sent out energy waves to divert our navigation to this world to take us over. The fact is, sirs, there are theories; the more reasonable ones do find credibility, where there’s secrecy with no evident, rational explanation for that secrecy. Werewe targeted to the white star? Isthere some mammoth conspiracy? Haveyou always known where Earth is? Was Taylor’s flight sabotaged?”

“Release the files,” Ramirez said. “The short answer is, Mr. Cameron, there’s no secret. They’ve been retained because negotiations have remained volatile, because we haven’t known how certain historical information would intersect your government’s opinion… the Mospheiran government, or the atevi. There were a couple of murders. Inflammatory history. And a damned lot about old Earth that we weren’t sure how the atevi would receive, and consider, frankly, none of their business to worry about. But no one’s history’s perfect. The main reason’s simply that they’re something Mospheira wants and something the atevi want, and we have them, until we know more about you. But in earnest of the agreement you set forward, I’ll release them. They didn’t exist on the station when we arrived. We theorize you must have lost them, probably in your notorious War of the Landing. We and the station storage now have redundant copies, and between you and us, Mr. Cameron, I’m anxious to see the collected works of our species replicated in a storage deep in a gravity well. We’ve stared extinction in the face, Mr. Cameron, and we wantthose files duplicated. They’ll be available within the hour. When you order transmission, we will transmit, in your name.”

Promoting himas an official contact point, not the Mospheiran delegation. He understood the game, he knew what Ramirez intended, and gave a solemn nod. “I’ll look at the nature of them as soon as I can; but again between us, I’d rather release them outright. Rumors are bound to fly on both sides of the straits, and I’d rather have those records for the theorists to digest right now, rather than let them work over the entire question of the agreement itself before they get them, or doubt that there might be anything in those files that might be associated. The more volatile elements are the very ones most interested in those records… and that have most to lose if those records contradict their universe-view. I say that in some faith they aren’t right and they likely won’t like all they read. But the news on Mospheira, I can tell you, will cover the records much more thoroughly than it will the details of the station agreement. If you want a smoke screen over what we do, yes, release the records. They’ll be an item in some footnote on the news of Shakespeare’s missing plays.”

“You evidence cynicism, Mr. Cameron.”

“Gentlemen, if I wanted to make Kroger a lasting hero on Mospheira, I’d give them to her. As it happens, I don’t want that. She’s not been in the position, and I rather cynically doubt she wants it, or would, if it happened. Mospheira’s hard on its public figures. It’s too small an island, with too many people, and too damned deep a dividing line between factions. I’ll rather ask you to transmit the files to the State Department and to the aiji tonight simultaneously, under your seal, and just let the pieces fall where they may, without politicizing Kroger. As far as I’m concerned, the agreement we reach will stand. The transmission is your way of proving your goodwill in current negotiations. It particularly favors Mospheirans, who value those files extremely; the atevi aren’t all that interested, since they reached technical parity with human culture, and you don’t need to say that the files in any way came from me. I don’t need the credit, but being in orbit, you can take the credit and not have lunatics phoning you in the middle of the night with religious visions.”

“You don’t want Kroger’s name on them.”

“I damned sure don’t want to give them to Kroger.”

“Personal animosity runs that deep.”

“No.” It did, potentially, but he wasn’t that mean-spirited, not against Kroger. But against those who might feel she was their representative, or who might turn her into that, definitely he held grudges, and suspicions. “Give the files to the world, gentlemen. Say it’s your gift. You’ll win good feeling on both sides, and if there shouldbe an informational bomb in those files, you’ll have defused it by being the one to release it, and Kroger and I will be completely safe. From that position, you can argue that you’ve been entirely open. That you’ve withheld them for three years becomes irrelevant. And if the Heritage Party on Mospheira discovers something it doesn’t like, that’s too bad.”

“Kroger doesn’t like you.”

“It’s her job to suspect the worst of me. Someoneneeds to question what I do. Too damned many people take my figures without checking them.”

Ramirez gave a slow, quiet smile. “Dealing with you over three years, Mr. Cameron, I’ve acquired an understanding of your ability to maneuver, to answer, and to calculate. You came up here prepared to agree; you have agreed. I’ll tell you I’m still astonished.”

“As I’ve dealt with you, I have considered you an ally. A sensible man. So is the President of Mospheira, so is the Secretary of State, and so is Tabini-aiji. The world is fortunate. The human race and the atevi are fortunate. We have reason to believe what you say and take you seriously. After all, the world’s been invaded from space once. Twice and three times would not be an astonishment.“

Ramirez’ brows lifted, then contracted in thought as he examined that concept, and perhaps realized he was the alien invader in question. “All right, Mr. Cameron, we’ll transmit the archive. Your channels will be open to it henceforth, in your quarters. Examine the files as you will. I do caution you that the designs you’re going to be working with are part of that download, however buried in detail. If there’s anyone on the planet you don’t want to have that technology, they will have it.”

That was worth a small, wry laugh. “Furtive construction of a starship?”

“Of weapons you don’t have, perhaps.”

“Mospheira’s manufacturing is good, but no better than the mainland, and falling behind by the hour. We’ve reached parity. Some few might want to misuse the files; but we’ve already come to mutual destruction and declined. We’ve learned to get along, Captain; in some part you’ve watched it happen.”

“Are you planning to go back at shuttle turnaround? Is that our time limit? I’ll tell you, we consider you too valuable to be running up and down in a gravity well in a relatively untested landing craft.”

“I can stay longer, but if you want my office to undertake a major new project, I’d rather be there to deal with my staff. And I intend to come and go. I’m worthless if I’m not where I can settle things. We have a limited time to set the details. If we’re to get workers up here, we have to arrange quarters and intensive, rapid training. We need room for five hundred, by our designs. Can I tour a similar, refitted area?”

“I can arrange that,” Ramirez said. “Whenever you ask, you’ll have a guide.”

“And a point we must agree to in principle. As you wouldn’t house the Mospheirans within totally black walls, you’ll expect certain aesthetic accommodations where atevi reside.”

“Aesthetic accommodations.”

“They are important, Captain. You want workers to work, there will be aesthetic changes, changes in the way the rooms connect…”

“We have no time to spend on aesthetics.”

He was very, very glad to hear that word time, a corroboration of every single point of negotiation over the last three years.

“So there are aliens.”

“Can you still ask that?”

“Damned right I can. And the walls won’t be this particularly objectionable yellow and the doors will be differently arranged… while we build your starship. I must warn you that the time will be a little longer than the three years we’ve already taken on the shuttle.”

“You’ve worked a damned miracle,” Ramirez said. “I need another one.”

“Another point. Potted plants will be very popular on the station, but these have to be removed to some other facility; we can’t have yours going down to the planet, no matter how innocuous the intent. We will observe a quarantine zone.”

“Understood. That becomes your problem.”

“It will be.” He drew a heavy breath. When he engaged with Ramirez, common sense arrangements tended to happen at a breakneck pace, and he wanted a space to consider the details. “I’m very content, gentlemen; the only other request I have is for radio contact with the planet, my schedule, my initiation.” Amid all the rest of the preparations, the designs on a vast, space-spanning scale, anguished small realization dawned on him, that he couldn’t honestly use personal privilege and call Mospheira on the phone. The best he could do was ask his office to mediate, or send off a letter or two he greatly feared wouldn’t pass Mospheiran security unexamined.