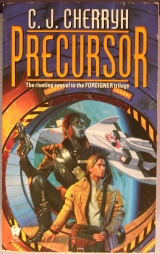

Текст книги "Precursor"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

And to his mother:

I’m on the space station, Mother. I’m attaching a letter I wrote to Toby. I love you very much, always. Bren.

He contacted Cl and sent both before he had a chance to change his mind, or before the difficulty of relations with the captains cut him off. He tried not to think how his mother would read it, and how much it would hurt.

But one hard letter beat a decade-long collection of niggling apologies that kept his mother hoping he’d change and kept Toby and Barb both trying to change him. That had eaten up years of trying; by now it was a lost cause.

His emotions felt sandpapered, utterly rubbed raw. He’d said good-bye to his mother, his brother, and the one human woman who loved him all in one package, all before breakfast.

He thought he’d done, in the professional case and the private one, exactly what he ought to have done: professionally, physically, for a moment on the line with Sabin he’d reached that state of hyperactivity in which to his own perception he could all but walk through walls, a state he knew was dangerous, since in the real world the walls were real. But the chances he took were part of his moment-to-moment consciousness; his position was something he didn’t need to research; his dealings with their isolate psychology was something he’d laid out in three years of working with Jase and hearing his assessments of the individuals. He wasn’t a fool. He scared himself, but he wasn’t a fool, not in his maneuvers with the captains.

The captains’ anger was real, however, and backed with force which—yes—if they were intelligent, they wouldn’t use.

Many a smart man had been shot by a stupid opponent. Not at all helpful to the opponent, but there the smart man was, dead, all the same.

And the psychological shocks bound to reverberate through his family… those were real, too. And he couldn’t avoid them. He couldn’t get to Mospheira. He wouldn’t be able to in the future. It was only going to get worse.

He went to breakfast, forced a smile for his staff, apologized, and felt not light-headed, but light of body.

He was still in that walk-through-walls state of mind.

The staff that was supposed to support him recognized the fact and went on doing their jobs in wary silence, and Narani went on bowing and doing properly the serving of tea and the presentation of small courses… he tried to restrain the breakfasts, seeing his nerves hardly left his stomach fit for them, but Banichi and Jago came to join him, and their appetites well made up for his.

“I’ve just insulted Sabin and told my mother neither I nor Toby can meet her future requests,” he said to them, “all before breakfast. What I sense around us, Nadiin, is a set of people on this station attempting to contain us, and to contain the Mospheirans, and to contain Jase… to hold, in other words, their accustomed power up here, or at least, to maintain their personal power relative to Ramirez. And by our agreement with Ramirez, none of these things should be happening. We have to push, just gently. I think we should take a small walk, if I can engage Kaplan-nadi.”

“And where should we walk?” Banichi asked him calmly, over miraculously fresh eggs.

“I think I’ll ask Kaplan,” he said. “I think we should survey this place they wish us to restore. I think we should walk everywhere. I began my report last night; this morning I have nothing but questions.”

“Shall we arm?” Banichi asked.

“Yes,” he said, and added, “but only in an ordinary fashion.”

Chapter 15

Kaplan appeared, kitted out as usual, electronics in place, opened the section door himself at the door with a beep on the intercom to announce his presence, and just came inside unasked.

Narani bowed, the servant staff bowed. Bren saw it all as he left his room.

Banichi, the security staff, and Kaplan all stared at one another like wi'itikiin over a morsel. The door to the security center was discreetly shut, good fortune having nothing to do with it, Tano and Algini were not in sight, and Bren didn’t miss the subtle sweep of Kaplan’s head, his electronics doubtless sending to something besides his eyepiece as he looked around.

“To the islanders, sir?” Kaplan asked.

“That, for a start,” Bren said, and went out, sweeping Kaplan along beside him, Banichi and Jago walking rear guard down the faded yellow corridors that looked like something’s gullet.

And he asked a flood of questions along the way, questions partly because he wanted to know, and partly to engage Kaplan: What’s down there?he asked. What’s that way?

“Can’t say, sir.” For the third or fourth time Kaplan said so, this particular denial at what seemed to be a relatively main intersection in the zigzag weave of corridors.

“Well, why don’t we just go there and find out?”

“Can’t take you there, sir. Not on the list.”

“Oh,” Bren said, lifting both brows. “There’s a list.”

At that, facing him and with Banichi and Jago looming over him, Kaplan looked entirely uneasy.

“Can we see this list?” Bren asked him.

“I get it from the exec, sir. I can’t show it to you.”

“Well” Bren said, and cheerfully rattled off in Ragi, “I think we might as well nudge gently and see what will give. Kaplan-nadi’s restricting what we see, but he’s not in charge of that decision himself. He’s getting his orders from higher up.—What would youlike to see, Nadiin?”

“Where does the crew live?” Banichi asked.

“Excellent suggestion,” Bren said, and looked at Kaplan, who did not look confident. “Nadi, where is the crew?”

“Where’s the crew, sir?”

“What do you do when you’re not on duty, Kaplan?”

“We go to rec, sir.”

“Good.” In some measure, despite the ferocious-looking equipment and the eyepiece, Kaplan had the open stare of a just-bloomed flower. “We should see rec, then, Kaplan-nadi. Or is that on the list of things we definitely shouldn’t see?”

“The list goes the other way, sir. It’s things you can see.”

“Well, that’s fine. Let’s go look at all of those, and then when you’re tired, we can go to this recreation place. That’s rec, isn’t it?”

“Yes, sir. I’ll ask about rec, if you like.”

“Why don’t you do that while we tour what we’re supposed to see? Take us to all those places.”

“Yes, sir,” Kaplan murmured, and then talked to his microphone in alphabet and half-words while they walked. “Sir, they’re going to have to ask a captain about rec, and they’re all—”

“In a meeting.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, tell them we just walked off and left you. All of a sudden I’m very interested in rec. I suppose we’ll find it. Are you going to shoot us?”

“Sir, don’t do that.”

“Don’t overreact,” Bren said in Ragi, “and above all don’t kill him. He’s a nice fellow, but I’m going to walk off and leave him, which is going to make him very nervous.”

“Yes,” Jago said, and Bren walked, as Banichi and Jago went to opposite sides of the corridor.

He’d give a great deal to have eyes in the back of his head. He knew, whatever else, that Kaplan wasn’t going to shoot him.

“Sir?” he heard, a distressed, higher-pitched voice out of Kaplan. Then a more gruff: “Sir! Don’t!”

Bren walked a few paces more, down a hall that showed no features, but the flooring of which had ample scuff on its sheen, leading right to an apparent section door.

He heard an uncertain scuffle behind him, and he turned, quickly, lest mayhem result.

Kaplan, going nowhere, had Banichi’s very solid hand about his arm.

“Sir!”

“He’s distressed,” he translated for Banichi. “Let him go, nadi-ji.”

Banichi did release him. Jago had her hand on her bolstered pistol. Kaplan didn’t move, only stood there with eyes flower-wide and worried, and rubbed his arm.

“Kaplan,” Bren said, “you’re a sensible man. Now what can we do to entertain ourselves that won’t involve your list?”

“Let me talk to the duty officer, sir.”

“Good,” he said. “You do that. You tell them if we’re going to repair this station, we have to assess it. Why don’t you show us one of the not-so-good areas?”

“I can’t do that, sir. They’re cold. Locked down.” He gave an upward glance at Banichi and Jago. “Takes suits, and we can’t fit them.”

“We have them. We could go back to the shuttle and get them. Or we could visit your ship. We’re supposed to build one.”

“Build one, sir. Yes, sir. I’ve got to ask about that.” Kaplan had broken out in a sweat.

“Come on, Kaplan. Think. Give us somethingworth our while. We can’t stand here all day.”

“You want to see the rec area, sir, let me ask.—But you can’t go in there with guns, sir.”

“Kaplan, you’re orbiting an atevi planet. There will never be a place an atevi lord’s security goes without guns. And you really don’t want them to, because if you have twoatevi lords up here at any point, without the guns, the lords are going to be nervous and there might not be good behavior. Banichi and Jago are Assassins’ Guild. They have rules. They assure the lords go to the Guild before someone takes a contract out on one of the captains. Think of them as law enforcement. There’s a whole planetful of reasons down there that took thousands of years to develop a peaceful way of dealing with things, and I really wouldn’t advise you to start changing what works. Why don’t we go somewhere interesting?”

“Yes, sir, but I still have to ask.”

“Do,” he said, and looked at a sealed, transparent wall panel with a confusing lot of buttons. “What do these do?”

“Lights and the temperature, sir, mostly, and the power, but don’t open that panel, sir, some of the sections aren’t sealed, sir.”

“Relax,” he said with a benign smile. He began to like Kaplan, heartily so, and repented his deliberate provocations. “Let’s go. Let’s go to rec. You’re a good man, Mr. Kaplan, and a very sensible one.”

“Yes, sir,” Kaplan said, still breathing rapidly. “Just let me ask.”

Kaplan was nothing if not dutiful. Kaplan engaged his microphone and did ask, passionately, in more alphabet and numbers, and nodded furiously to whatever came back. “Yes, sir,” he said finally. “They say it’s all right, you can go to rec.”

“Let’s go, then,” he said. “And do you have a cafeteria? The mess hall? Shall we see that?”

“That’s on the list, sir.” Kaplan sounded greatly relieved.

“Good,” he said. “Banichi, Jago, we’ll walk with Kaplan-nadi. He’s an obliging fellow, not wishing any trouble, I’m sure. He seems a person of good character and great earnestness.”

“Kaplan-nadi,” Banichi said in his deep voice, and with a pleasant expression. “One would like to know what he does transmit to his officers.”

“Banichi wants to know what you see and send,” Bren said. “Such things interest my security.”

“Can’t do that,” Kaplan said, all gruffness now.

“Buy you a drink?” Bren said. “We should talk, since you’re to be my aide.”

“I’m not your aide, sir. And I can’t talk, sir. I’m not supposed to.”

“Aren’t you? Then I may request you. I’ll need someone when I’m on the station. Are you married?”

“Married, sir, no, sir.” Kaplan’s nervousness only increased.

“Where do youlive?”

“238C, sir.”

“That’s a room?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Alone?” Bren asked.

“Two and two, sir, two shifts.”

“In all this great station? You’re doubled up?”

“On the ship we had more room,” Kaplan said. “But they’re working on the ship.”

“Doing what?” Bren asked.

“Hull, mostly.”

“Damage?”

“Just old, sir, lot of ablation. And when she’s in lockdown, it’s not easy to be aboard; you can’t get a lot of places in zero-G, sir. See those handholds? Not much use on a station, but on a ship, that’s how you get by if you have to crawl.”

It gibed with what he knew from Jase. While he kept up a running interrogation on points of corroboration, it was more corridors, more turns, twists, and descents, not a one of them distinguished from the other except by the occasional wall panels. It was an appalling, soul-numbing stretch of unmarked sameness.

They came to a corridor with one open door.

“This is rec, sir,” Kaplan said, and led them to a moderately large room with a zigzag interior wall—a safety consideration, Bren knew by now—and a handful of occupants. The decor consisted of a handful of very faded blue plastic chairs, all swivel-mounted, at green wall-mounted, drop tables. Most astonishing of all there was a decoration, a single nonutilitarian blue stripe around the walls. There was, besides the stripe, a bulletin board, and a handful of magnetically posted notices.

Crewmen, doubtless forewarned, rose solemnly to their feet as they came in.

“Gentlemen, ladies.” Bren walked past Kaplan, walked around the walls, keeping a careful eye to the reaction of the crew to Banichi and Jago… fear, curiosity, all at the same moment. The crewmen wanted to stare and were trying not to. “Good day to you,” Bren said, drawing nervous, darting stares to himself. “I’m Bren Cameron, emissary from the aiji at Shejidan. This is Banichi and his partner Jago, chief of my house security, no other names. Think of them as police. Glad to meet you all, gentlemen, ladies.”

“Yes, sir,” some said. Those terms had fallen out of use. He was an anachronism in their midst, or he was their future.

“Seems we have an agreement,” he said, curious how far news traveled among the crew. “We’re going to be building here. Mospheira’s going to provide you all the comforts of the planet, up here, according to what we’ve settled on, everything from fruit juice and hot dogs to seat cushions. Jase Graham. You know the name?”

They did, though there wasn’t a clear word in what they answered. It was Kaplan’s wide stare replicated, one and the other, men and women.

And he’d bet the place had been cleared of anyone not on a List, too.

“Jase is a friend of mine. Friend. You may have heard—or you may hear—you can’t say that with the atevi: that they don’t quite work that way. That’s true. But it doesn’t mean you can’t get along with them and that they aren’t very good people. You have to figure out associationswith them. For instance, if you get along with me, you know you can get along with my security, my staff, my associates, and everyone I get along with. There’s no such thing as one ateva. It’s really pretty easy if you ask the atevi what they think of the other ateva you plan to be nice to. Glad to meet you all. My security is glad to meet you, no one’s going to shoot anyone. Don’t mind that they don’t smile. It’s not polite to smile until you know each other. Kaplan.”

“Sir!”

“Introductions, if you please.”

“Yes, sir,” Kaplan said, and proceeded solemnly to reel off every name, every job, and rank: there were Johnsons and Pittses and Alugis, there was a Shumann and a Kalmoda and a Holloway, a Lewis, and a Kanchatkan, names he’d never heard. They were techs and maintenance, all young but one, who was a master machinist. “Glad to meet you,” Bren said, and went around shaking hands, doggedly determined to put a face and a name to what had been faceless for two hundred years and three more in orbit about the planet. “My security won’t shake hands. Our culture is foreign to them. They find you a fortunate number, they compliment you on that fact; they find you a comfortable gathering. I believe your library has a file on protocols when talking to atevi: I know I transmitted that file a couple of years ago, and hope it’s gotten around.”

No, it hadn’t. He could tell by the looks. And he was far from surprised.

“Well, I hope you’ll take a look at it on a fairly urgent basis, since there will be atevi working here. And don’t take humans from the planet completely for granted, either. From your viewpoint, they’re quite different, and words don’t mean quite the same; I was born on the island, myself, and I can say you don’t at all sound like Mospheirans. What doyou do for entertainment, here?”

“Games, sir.” That from a more senior crewman. “Entertainment files.”

“Dice,” another said.

Jase had said entertainment was sparse and opportunities were few. Jase had been vastly disturbed by rapid input, flickering shadows, any environmental phenomenon that seemed out of control: Jase standing on a deck on the ocean under a stormy sky was far, far beyond the bounds of his upbringing… an act of courage he only comprehended on seeing this recreational sterility. “Jase enjoyed his planet stay, gathered up some new games. I know he sent some footage up.”

It hadn’t made it to the general crew. There were blank glances, not a word.

“Definitely, we have to talk about the import situation,” he said, with a picture he really, truly liked less and less. “I’m sure the Mospheirans will offer quite a few things you might like.” Give or take the whole concept of trade, which he wasn’t sure they really understood on a personal level. “You’ll have a lot of things to get used to, among them the very fact of meeting people who aren’t under your captains’ orders, who speak your language and mean something totally different. Who don’t mind surfaces bouncing around under them and lights flashing and who are rather entertained by the feeling.” The looks were somewhat appalled. “We, on the other hand, will be largely involved in construction: improving the station, providing fuel, materials, that sort of thing. And we understand you found a problem out in far space. We’re used to dealing with strangers. We hope to deal with your difficulty and solve it.”

That struck a chord, finally. That was something they understood… and didn’t believe.

“Yes, sir,” came from another one, whose name was Lewis. Bren hadn’t forgotten, didn’t intend to forget a single name.

“Have you talked to Jase since he’s been back?” he asked.

“No, sir,” one said, and there were various shakes of the head.

“Interesting,” he said, and had a very uneasy feeling about this place, about the crew, about the whole situation. “But you do know him.”

“Yes, sir.” They seemed to take turns talking. Or they were all wired, like Kaplan, getting their answers from elsewhere.

“Kaplan,” Bren said.

“Sir!”

“Why don’t we take a walk to the Mospheiran delegation, and then over to the mess hall?”

“They’re in the same section, sir.”

“Well, good,” he said. “Why don’t we do that?”

“Yes, sir,” Kaplan said.

“Would any of you like to walk along?”

“We have to get back to duty,” one said.

“I’m sure you do. Well, good day to you all. Hope to see more of you.” Bren smiled and made his withdrawal, saying, in Ragi, still smiling, “Jase was wildly extroverted when he arrived, compared to these people.”

“They seem very afraid,” Jago remarked.

“They seem afraid,” he repeated, following Kaplan. “They were likely put here for us to see. They haven’t seen Jase, and they haven’t seen any of the files we’ve transmitted up, the ones about atevi.”

“One certainly asks why,” Banichi said.

“One certainly does ask,” Bren said. “Kaplan, what are these people scared of?”

“The aliens, sir.”

“Banichi and Jago aren’t aliens. You and I are. That below is their planet.”

“Yes, sir.” Kaplan didn’t look reassured. Nor was he reassured, regarding the ship.

“Ever been in a fight?”? Bren asked.

“Sir?”

“Ever had to fight, really fight, hand to hand?”

“No, sir,” Kaplan said.

“Has anyone on this ship ever been in a fight?”

“I don’t think so, sir, well, a few scrambles between us, but not outside, sir.”

This from a man overburdened with direction-finding, recording, and defensive equipment, a man who looked like a walking spy post.

“Bren.”

“Sir?”

“Bren’s the name. You can call me Bren. For formal use it’s Bren-nandi, but Mr. Cameron is my island name. Is Kaplan what you go by?” Last names were stitched on every uniform, and it was all uniforms, completely identical. Textures had frightened Jase. Differences had frightened Jase. He saw now that everything on the station was one color, the uniforms were all alike: the haircuts were generally but not universally alike… one size fit everyone and one had to train one’s eye to look at subtler differences, which probably were quite clear to someone who knew the body language of every individual aboard. He supposed that Kaplan could recognize an individual from behind and at a distance down the oddly-curving corridors, and that he himself was relatively handicapped in not knowing. The difference he posed must certainly be a shock; the Mospheirans no less so; and what they thought of the atevi was likely like a man looking at a new species: the ability to integrate patterns and recognize individuals utterly overwhelmed by a flood of input, not knowing what was a significant difference.

Three years to build a shuttle?

Three years to bring Jason, who was trying, into synch with atevi ways?

It wasn’t the engineering that most challenged them in building here. It was the psychology of individuals on the ground who for various reasons didn’t want to comprehend, the pathology of individuals having trouble enough inside their own system of recognitions; the pathology of a human society up here walled in and sensitized to a narrow range of subtle sensations, subtle signals.

He’d been uneasy regarding Jase. In Jase’s continued, defended absence, he was growing alarmed, pressing harder. He knew the hostility in his own mind toward these people who were behaving in a hostile way, and dare he think he was part of the difficulty?

It was a long walk through unmarked territory. More and more unmarked, unnumbered territory before they reached the Mospheirans, before sentries admitted them, unquestioned, at least, on Kaplan’s presence, if nothing else. They walked into the small district, drew a curious response from Lund and from Feldman, who walked out from separate rooms.

“Come have a drink,” Bren said. “The cafeteria’s buying.”

Lund and Feldman stared at him. Kroger and Shugart showed up, equally suspicious.

“Our hosts are hostile in manner,” Bren said cheerfully in Ragi, a simple utterance, given the basic vocabulary of the translators, and Feldman and Shugart betrayed a quickly-subdued uneasiness.

“A good idea,” Feldman said with some presence of mind. “We should go.”

“Go, hell,” Kroger said. “What are you up to?”

“Listen to him, Nadiin,” Jago said, and by now Kaplan was looking at one and the other of them.

“Kaplan,” Bren said, laying a presumptive, hail-good-fellow hand on Kaplan’s wired shoulder, “Kaplan, my friend, is there a bar to be had?”

“There is,” Kaplan said.

“Is it on the List?”

“Yes, sir,” Kaplan said.

“Well, let’s all go there and have a drink.” He tightened his grip as Kaplan began to protest. “Oh, don’t be a stick. Come along. Be welcome. Show us this bar.”

“Sir, I can’t drink on duty.”

“I’m afraid for what the stuff is made of,” Bren said, ignoring Kaplan’s reluctance, and pressed to turn him about. “But I’ve gone long enough without a drink.”

“Sounds good,” Lund said, but Kroger was frowning.

“Feldman, you stay” Kroger said. “All right, Cameron. I hope you have a reason.”

“A perfect reason. Kaplan, is there any chance you can liberate Jase to join us?”

“I don’t think so, sir. He’s with the captains.”

“Well, come along, come along. Feldman, my regrets.”

“Yes, sir,” Ben said confusedly.

At least Kroger hadn’t robbed the bar party of both translators. And she’d left security behind.

They set off back past the sentries. Another walk, a short one, and there was, indeed, a small bar, the most ordinary thing in the world to the Mospheirans, one he himself hadn’t thought of untilhe’d walked in among his own species, and one of the most astonishing places in the world for Banichi and Jago, surely. It was dim, it smelled faintly of alcohol, a television was playing an old movie on the wall unit, and every eye turned toward them.

“This is a place,” Bren said in Ragi, “where humans meet to consume alcohol, talk, and play games. Hostilities are discouraged despite the loosening of rules, or because of them. It substitutes for the sitting room. Here you may sit and talk while drinking. Talk with the young paidhi while I talk with Lund and Kroger, find out what she knows, advise her honestly of our concerns, advise her how to communicate this discreetly to her superiors. It is permissible and encouraged to lean on the counter where drinks are served while one talks.”

“One will try,” Banichi said.

“Shugart,” Bren said, “go practice your translation with them, using no names.”

“No names.” The word was difficult in Ragi.

“Lund,” Bren said, flinging an arm about the delegate from Commerce. “What will you have? More to the point, what have they got, Kaplan? Vodka, more than likely.”

“There’s vodka,” Kaplan said. “There’s vodka and there’s flavored vodka.”

“I’m not surprised,” Bren said. “Is there anything you can’tmake into vodka?”

“I don’t know, sir,” Kaplan said. The eyepiece glowed in the dim lighting. Unhappily, so did atevi eyes, as gold as Kaplan’s eyepiece was red. The phenomenon drew nervous stares around the room… from the single bartender, the five gathered at a table. The stares tried not to be obvious, and weren’t wholly friendly.

“Anyone here know Jase Graham?” Bren asked aloud. If there was anyone who didn’t, they didn’t say so, but neither did the others leap up to say they did. “Friend of mine. Missing onboard.”

“He’s in the captains’ debriefing, sir,” Kaplan said under his breath.

“I know you say that. Here. Sit down.”

“I can’t…”

“Can’t sit? You look perfectly capable to me.”

“Yes, sir,” Kaplan said, “but I can’t drink.”

“You can have a soft drink; I’ll assume there’s something of the sort here.”

“Yes, sir,” Kaplan said. They sat. The bartender came over as if he were approaching hostile lunatics. “Fizzwater,” Kaplan said.

“What flavors does the vodka come in?”

“There’s lemon and there’s pepper.”

“I think I’d play it safe,” Kroger said, “and ask for plain. With ice.”

“Sounds like good advice,” Bren said. “Plain.” Lemon was a flavor; historically it had been a fruit, but there was no such aboard Phoenix;and peppers, while some grew on Mospheira, were mostly native. It was a matter of curiosity, but not when one courted information, not new flavors.

The drink orders went in. Banichi and Jago talked in Ragi with the wide-eyed young translator. The drinks arrived, indifferently served, and their guard had a fizzwater while they knocked down untrustworthy vodka.

“Kaplan’s been touring us about,” he said in his thickest Mosphei’ accent. “We’d really wanted to do this with Jase, who can’t be found. I did get a call through to the mainland and sent one off to Mospheira; Tabini-aiji is quite pleased; I hope the President will be.”

“We’ve put in a call,” Kroger admitted, continually looking at her glass and her fingers, as if there were high counsel there. “We’re going to work up some figures. We’ve been at it, actually.”

“So have I,” Bren said, and they proceeded to talk detailed business while Kaplan sipped his fizzwater and the vodka worked on their nervous systems. Kroger relaxed a degree; Lund grew positively cheerful; whether either took the warning about Jase’s disappearance Bren remained uncertain, but he hoped Banichi and Jago were getting past the language barrier. He heard nervous laughter from Shugart, saw her duck her head in utter embarrassment, and saw Banichi and Jago both laughing, which was encouraging.

The whole bar relaxed, with that. The conversation between Banichi and Jago and Kate Shugart began to involve the bartender, evidently regarding the television. First the bartender changed the channel and punched buttons and then while business talk proceeded at their table, Banichi and Jago investigated the buttons, while Shugart translated and investigated the buttons herself.

And after two drinks, numbers exchanged, opinions exchanged in some quiet amity, and definitely more relaxed than he had been, Bren called an end to the visit. “Well,” he said, “better go get back to quarters, see if there’s a hangover in this stuff.”

“Doesn’t seem too bad,” Lund said, who’d had three.

“Best we go, though,” Kroger agreed.

“But we should give an official hello,” Bren said. Perhaps it was the vodka, but his motives were sheer public relations, since things were going so well at the bar. He went over to the other table and had Kaplan introduce him and introduce the others, including Banichi and Jago, who never yet had spoken a word of Mosphei’, and who met the five crewmen with uncharacteristic smiles.

“Very glad to meet you,” Bren said, and went through the most of the routine a second time with the bartender, whose name was Jeff, and who, yes, had shown them the workings of the entertainment system.

“Can they see in the dark?” Jeff wanted to know, further, on what Bren estimated was the chatoyance of atevi eyes.

“A little better than we can at twilight,” he said, knowing as a human how people who saw in the dark played off human fears… and then remembering this Jeff would have no visceral concept of twilight. Dusk and dawn were no better. “Like in here,” he amended that. “Not sure about the color range, well as we know each other; don’t think it’s ever been tested scientifically. But it’s not that much different.”

“Huh,” Jeff said thoughtfully, and Bren gave the polite formulas and gathered his party out the door into the corridor, Lund tending to stray a bit. They were cheerful, the lot of them, even Kroger looking flushed.

“Well, probably time we got back to our various sections,” Bren said. “Why don’t you drop by tomorrow? We can give you something a little aside from the cafeteria fare. I have to let my staff know in advance, but no great difficulty to set a few extra places.”

“I don’t know,” Kroger said.

“Anything but the food up here,” Lund said, and then cast a look at Kaplan. “With apologies.”

“Everything my staff brought accommodates human taste,” Bren said. “Kaplan, can you bring them for supper tomorrow, say, oh, local eighteen hundred? You’re welcome, yourself. Plan to eat with us.”

“I can’t, sir, not on duty.”

“Your duty is a bother.”

“Yes, sir,” Kaplan said. “But I have to do it.”

“All the same. You can have a cup of tea and a wafer or two. The universe won’t end.”

“Eighteen hundred,” Kroger said.

“Granted we survive the hangover,” Bren said. “Lead on, Kaplan. Show us the way.”

Chapter 16

“One does apologize, Nadiin-ji, for curious behavior,” Bren said when they met the staff, he and Banichi and Jago with Tano and Algini as interested bystanders from the security room door.