Текст книги "Under the Big Top: A Season with the Circus"

Автор книги: Bruce Feiler

Жанры:

Прочие приключения

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

An American Dream

The dream, in the end, begins with flight.

“Ladies and gentlemen, our featured attraction, the World’s Largest Cannon…!”

Inside the big top the anticipation soars as the back door opens for the final time and the world’s largest cannon slowly rolls into view—its siren wailing, its flashers beaming, and its barrel growing foot by foot with every gasp from the audience and every camera flash. Standing atop the silver barrel is the newest American daredevil himself. At first he looks like Elvis, only blond. Then Superman, only shorter. But when he finally arrives in the ring, with his blue eyes and blond hair aglow in the light and his white rhinestone suit shimmering like a torch with red and blue star-studded racing stripes, Sean Thomas looks taller than God.

“Introducing…the Human Cannonball…Seaaaaan Thomas…”

As Sean salutes and waves to the crowd, the seventy-five or so members of the cast line up just behind the back door and prepare to stream into the tent like apostles at the second coming. The atmosphere backstage is ripe with excitement, though slightly tinged with rue—another season passes safely, another year is borne by the body. As the performers inch into position most are busily saying goodbye; as soon as the show closes tonight in Palm Beach the cast will scatter in a dozen directions. A few are thinking of retiring—Venko Lilov, Dawnita Bale, even Jimmy James himself. Many more are thinking merely about going home—Michelle and Angel are heading to Spain; Sean and Jenny are going on a honeymoon; and Danny Rodríguez, who in the end said he didn’t like the pressure of earning money and missed being a performer, is returning home to Sarasota with his mother and father.

I am truly going home: this show will be my last. Earlier, feeling celebratory, I asked Fred Logan if I could ride an elephant during spec of the last performance. With a silent nod and a gruff thumbs-up, he led me to the end of the elephant line and called for the last bull in the herd to kneel down. I placed my left foot on her right front leg, and without so much as a hint of strain she hoisted me almost ten feet in the air and all but flung me onto her back. Upon landing face-first on her shoulders, I was so surprised by the scratchiness of her skin and the intense heat from her neck that it was not until I tucked my legs behind her ears and dangled my shoes beside her face that I looked down to pat my three-ton chauffeur and realized that I was sitting on Sue, whose fortitude during surgery a year earlier had drawn me into this circus and whose strength this final night would carry me out.

By the end of the evening as the moment approached for me to walk into the finale, I was feeling more nervous—more excitable and tense—than I had felt on opening day. At that time all I had noticed were the bodies and props of all the nameless people around me; now I felt the devotion and faith that ran throughout the company—more congregation than corporation, more cult than cast. Indeed, I felt a bond with this community that was greater than any I could recall feeling with any other group outside my family. The feeling is what I imagined military camaraderie to be like: the people on the show may have come from different backgrounds, we may have had different aspirations, but for nine months on the road we traveled to hell and back together and emerged in the end slightly wounded for sure but almost fanatically devoted to one another and to our near-religious cause. Onward, circus soldiers: the world needs your message of hope. And on that final night of the season the mood of fellowship was everywhere ascendant. Just before I stepped through the door with all the other clowns, Marty tapped me on the shoulder and offered his arms in embrace. “Well, Bruno,” he said, “you did it. I don’t know what kind of writer you are, but I know you’re a hell of a clown.”

“And the stars of the Clyde Beatty—Cole Bros. Circus…”

At last I step into the lights. The ground seems light beneath my feet. With waving arms and beaming face I dance to the lyrics “Join the circus like you wanted to when you were a child…” In a moment I arrive in the front of ring three and stand beside the passenger door to the cannon, where the silver lettering announces GUN FOR HIRE. In ring one the giant yellow-and-blue air bag is being filled by means of portable fans. In between the bag and the barrel the cast slowly arrive at their places and stand solemnly at attention as if pointing the way for the gun to fire.

“All eyes on the giant cannon…”

The music changes to a fearsome dirge as the mouth of the thirty-foot silver barrel slowly rises into the air. At the top of the barrel Sean surveys his path. His face is etched with well-worn concern. His eyes squint in the manner of a ten-year-old boy trying to remember the answer to a test. His whole body seems remarkably slight.

“Lieutenant Thomas prepares to enter the gun barrel…”

With one last tuck to keep his hair in place, Sean slides a white helmet over his head, removes the temporary foam lid from the mouth of the cannon, and flings it almost casually in my direction. At the start of the year, when I was still unsure on my feet, this manhole-sized cover would often hit me in the head and knock me from my place. By the middle of the season, much surer-footed, I started trying to catch it in the air. By year’s end, I was nearly fleet of foot, and Sean’s throws became more challenging. I would often snag the lid with an artful flourish, as I do on this final night of the year. The audience flickers with applause: the Human Cannonball is jamming with a clown. The ringmaster beckons us back to our tasks.

“A final farewell…”

Sean positions a pair of lemon goggles over his eyes and scampers into the open barrel. Before his head disappears from sight he waves goodbye to both sides of the house and gives a final thumbs-up to the crowd. Then in a sequined flash he is gone. The music suddenly skids to a halt. Only the pulse of the tympani drum disturbs the spreading silence. The pause is almost painful to bear. The tent is dense with fear. Jimmy James augments the alarm.

“With an ignition of black gunpowder, combined with the chemical lycopodium for safety, he will blast off at a safe speed of fifty-five miles per hour…”

Ta-dum! The drumroll grows even louder. Oh no! The children cover their eyes. Please! I whisper to myself even after five hundred shots.

“Countdown!” Jimmy calls, and all the performers raise their hands in salute. With each booming call from his proud bass voice the audience joins the cry.

“Five.

“Four.”

Until every voice in the six-story tent begins to chant in rare harmony.

“Three.

“Two.

“One…”

And all our dreams confront their test.

“Fire!”

Inside the barrel Sean Thomas waits.

“When I first get in the barrel I check all the parts. I look at the slide to make sure it’s all greased. I look at the cable to make sure it’s not snagged. Then after I rest my butt on the seat and put my feet on the stand I look out through the mouth of the cannon to make sure I’m pointed in the right direction.”

Outside Jenny stands at the controls—four levers and a series of flashing lights—and makes the final preparations. She wears a headset to communicate with Sean. A small video screen reveals the distance the launching capsule has been retracted. Every show the measurement is adjusted. Though the front of the cannon is always precisely one hundred feet from the front of the bag, the amount of power Sean requires depends on the density of the air, the slope of the lot, and the relative strength of the cannon propulsion system itself.

“There’s no reason anything should go wrong,” he said. “It’s pretty close to a science.”

Not particularly scientific himself, Sean approaches each date with the cannon as if he’s preparing for battle.

“I call it the Beast,” he said. “Elvin says be friendly to it and it will be friendly to you. But it can turn on you like that. It can kill you in an instant. It’s like the enemy and we’re at war. I feel like it’s always trying to get me, so I’ve got to find another angle. Every show it’s something else. Every day it’s like wrestling with fate.”

Lying prone in the capsule with his rear end on a saddle, Sean prepares for battle. He grips his fists alongside his face and looks once more toward the mouth of the barrel.

“Inside, just at the lip of the cannon, there’s a bumper sticker that says: ‘NO GUTS NO GLORY.’ I used to have a surfing T-shirt that said that. There was this big wave and this tiny guy who was just a dot on the shirt. It was my favorite shirt, but it got ruined the first night I wore it. I got into a big fight and blood went everywhere. Later I saw the sticker and put it in the cannon. It’s the only thing that keeps me company.”

From his pad Sean announces he is ready. From her post Jenny passes on the word. From the ring Jimmy informs the world.

“Countdown.”

Inside, Sean receives the command as it echoes down the solid-steel barrel. When he first slid into the cannon, two years earlier, Sean was reckless, even cavalier. Even at the start of his second season, he was ruthless with the Beast—kicking it, beating it, tempting it to challenge him. But by year’s end he had been transformed.

“Five.”

“I’m much calmer now,” he said in the front seat of the cannon just minutes before his final shot. He was listening to Percy Faith love songs on the cassette player in the dash. A picture of Jenny was taped next to the speedometer. The handle of his white plastic brush was broken in two. “I’m a much better person than I used to be. I don’t know if it has to do with reading the Bible or what. I think it has more to do with getting married and kind of growing up a little bit.” His voice was lower than it was when I first met him. He was less likely to punch me in the arm for fun.

“Four.”

“Now I have responsibilities,” he continued. “I don’t just worry about myself. Before, I didn’t even do that. Now I have to worry about somebody else. Plus myself. I have to feed her. I have to clothe her. She doesn’t work anymore. Before, I didn’t have anybody depending on me. Now I have to worry about what I do in the cannon, because if something happens to me in there, then she’s left all alone.”

“Three.”

As with his view of himself, Sean’s view of the show had also evolved. The first day I met him he climbed on the cannon and left me standing on the ground. “So, you want to have a peek inside?” he had taunted. “Why not,” I had said. “Because you can’t,” he replied. For weeks afterward I accepted his challenge and began piecing together the “world’s largest secret.” Much of it was simple. Inside the barrel was a coffin-sized capsule attached to a narrow cable; the capsule was pulled back into launching position by a hydraulic piston; the piston locked the capsule under the handle of a giant mechanical trigger. But what was it that gave the capsule the power to launch the cannonball? At first I thought a spring, or maybe even the explosion itself. Both of these were wrong, I soon discovered, though I couldn’t figure out why.

“Two.”

Finally, about a week before the end and with our friendship well established, the newly humbled Human Cannonball invited me inside the barrel. There I saw Sean’s bumper sticker. There I felt his source of flight. There I heard the silent echo of every child who hoped to fly.

“One.”

And there I realized that certain dreams are better left preserved.

“Boom!”

Emerging from the cannon, Sean looks like a blur. His body shoots from the barrel like a cork from a champagne bottle, bursting fifty feet into the air with a shower of bubbly oohs and aahs and an explosion of speed and light. Halfway to heaven his arms slowly open as if he’s swimming toward the top of the tent. Then for an instant he seems to stop—he’s reached his peak, he’s mounted the sky—before he finally ducks his head and begins his final descent.

“Flying is the greatest sensation,” he said. “When I take the hit and leave the barrel I feel as if I could fly forever. That’s when I know I can do anything. My mind slows down. I know I’m going to hit the bag. And then at the peak my momentum stops and finally I feel that I’m free-falling. Falling, falling, falling, falling, then, boom!, I land on my back. It’s not like anything in the world. It’s not like diving off a diving board. It’s not like surfing on a wave.”

“Is it like sex?”

“What, are you nuts? I mean it’s good, but it ain’t that good! It doesn’t make me blow a nut.”

Sean lands in the bag with a giant puff. I breathe my final smile of relief. The audience slowly rises to its feet as Sean steps out of the yellow-and-blue pond with a slightly dazed look on his face. He tosses his helmet to the prop boss and skips to the center ring.

“Ladies and gentlemen…the Human Cannonball…Seaaaaaaaan Thomas…!”

Sean plants his feet slightly apart, lifts his arms high into the air, and beams at the last row of the crowd as if to say, “Hey, look, I did it. Now let’s hear some applause.” For a full minute he draws that applause, and at the end of that time he looks off to the side, where Elvin Bale has returned for the final show of the year and is sitting in his wheelchair with his arms in the air like a proud parent who watches his child succeed and knows just how it feels.

“Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, you have just witnessed another milestone in American show business history….” Jimmy straightens his red tailcoat and steps to the center of the world’s largest tent. “Tonight’s performance concludes a ninety-nine-city tour, through sixteen states, covering over twelve thousand miles, and giving five hundred and one performances. None of it would have been possible without you, the American circus-going public. We sincerely thank you for your patronage…”

With a final blow on his ringmaster’s whistle and a gentle sweep of his arm toward the door, Jimmy draws the season to a close. The band marks the moment with a teary rendition of “Auld Lang Syne.” The cast quickly streams from the tent. Outside, the performers barely pause at the door before sprinting to their trailers and shedding their spangles for the final time. Quickly, desperately, they want to be free.

The last person out of the tent is the ringmaster himself. Not so fast on his feet, less desperate to flee, Jimmy slowly pads from the tent with a fog of tears eclipsing his eyes. His smile is weary. His bow tie is gone. In his hand he carries a small tote bag.

“So now you know…,” he says as he stops by my side.

“Yes, I do,” I reply. We both shake hands.

“I hope you tell the truth,” he says. “Soon all of this will be gone.”

Back in the Alley the others have gone. I slip off my oversized red-and-white shoes and unhook my floppy gold tie. Piece by piece I remove my costume: my bright orange pants, my white dinner jacket, and my pointy hat with the elastic strap. I fold each of these and lay them in my trunk, already battered from three weeks on the road. At last I slip off my stained skullcap and queen-sized stocking hair net. The only thing left is my bright white face, with the smooth black clefs and the crisp red nose. Squeezing baby oil into my hands, as I have done more than two hundred times before, I smear it into my pores and rub the graphic red and black features into the layer of solid white that covers my skin from my forehead to my throat. After several quick wipes with a well-stained towel my face dissolves into its former self, like a black-and-white negative slowly changing into color. I look at the mirror that hangs in the corner and the image reflected is clearly mine. Instinctively I try to smile, but the truth is painted all over my face. I am myself.

By the time I step outside, the city is already halfway torn down. The flying rigging is being dismantled. The tympani drum is being carted away. The bears and tigers have already gone. By twenty after ten the last lights have come down, leaving behind the empty whale where elephants and horses so recently danced. A few men pull down the outer poles. Ropes dangle everywhere. In a moment a light mist begins to fall. By eleven o’clock the tent is dark. All the seats have been removed. All the magic has been excised. One by one the quarter poles are released and the heavens are slowly winched down to earth, until at twenty minutes before midnight, with a silent, swelling slap, the world’s largest big top spanks a final time against the pale, wet Florida grass. Few people are around to witness the sight—the crew, a few of the mechanics, and, fittingly, the owner.

Johnny startled me moments later as I watched the men dismantle the center poles into their male and female halves. His voice was valedictory. His eyes were heavy. “A long time ago I learned that there are many things in life that I wished I’d looked at just a little longer,” he said. “I always think I might not see it again and I want to remember it. I used to do that with my home. When I left home every spring to go on the road I would walk around the house a little bit. I would wander through the flower beds and the lawn. The trees are here, I would say to myself. The house is here. They might not be here when I get back. It’s the same way with the show. I’m always afraid that something will happen to me, or to the circus, and I might never see it again. One year I will be right.”

Quietly and with casual sleight of hand he produced a bag from behind his back and laid it in my arms.

“I want you to have this,” he said, “and I want you to know: no matter what else, you were a damn good clown. You made our show better this year.”

I thanked him for his generosity, then peered into the bag. Inside were several bundles of faded cloth, four tattered talismans: CLYDE BEATTY, COLE BROS., CIRCUS, and on top of the others, the American flag.

“You can never say goodbye to the circus,” he said, “no more than you can ever say goodbye to your childhood. We’ll see you again. I’m sure of that. Now you’re one of us.”

Johnny shook my hand and walked away—vanishing himself in the cover of darkness like the show he so adored. Left alone, I followed his cue, and with one last look at the rolled-up tent, now easing around its spool, I started my camper and drove off the lot—onto a road without any arrows, toward a tomorrow without a circus.

Home

Behind the Painted Smiles

One lingering effect of my year in the circus is that various words now mean different things to me than they do to the rest of society. One of these is the word “clown,” which I am distressed to observe has developed a surprising currency as an insult. Another is the word “circus,” which has somehow come to mean “chaos,” as in “It’s a media circus out there” or “My office is a three-ring circus.” After watching the world’s largest big top go up and down ninety-nine times and seeing two hundred people and two dozen animals move twelve thousand miles and do five hundred and one performances in slightly over eight months, I can say with a certain degree of confidence that I have never been around anything as well organized as a three-ring circus.

With that in mind I would like to thank the two hundred men and women of the 109th Edition of the Clyde Beatty-Cole Bros. Circus, many of whom appear by name in this book. Their dedication is boundless, their skills unrivaled, and their unflinching hospitality in the worst of conditions made me a believer in the magic of the circus. In particular, I would like to thank the following people who welcomed me into their lives: Khris Allen; Gloria, Dawnita, Elvin, and Bonnie Bale; Elmo Gibb; Blair and Mark Ellis; the Estrada Family; Nellie and Kristo Ivanov; Jimmy James; Kris Kristo; Inna and Venko Lilov; Fred Logan and Family; Michelle and Angel Quiros; the Flying Rodríguez Family; Jenny Montoya and Sean Thomas; Royce Voigt; and the boys in Clown Alley: Brian, Christopher, James, Jerry, Joe, Marty, Mike, Rob, and Buck.

In addition, I would like to express my heartfelt appreciation to the men and women of the advance and marketing department (Jeff Chalmers, Bob Harper, Elizabeth Harris, Bob Kellard, Mike Kolomichuk, Tim Orris, Edna Voigt, Chuck Werner), and especially to Bruce Pratt and Renée Storey, whose encouraging words and spirited laughter have made them seem like equal collaborators in this project. Finally, my deepest appreciation goes to E. Douglas Holwadel and John W. Pugh, who invited me to join their show without restrictions and who guided me openly through the normally candy-coated corridors of the circus. Johnny Pugh, still on the road more than fifty years after being born into show business, is one of the most respected men in the circus business today and one of the most decent men I’ve ever met.

Meanwhile, an equally large number of people who don’t live on wheels helped bring this book to life. Jane Dystel, my agent, cradled this book from gleam to reality. Bill Goldstein, my editor, nurtured it from proposal to publication. Miriam Goderich read an early draft and made several helpful suggestions, and David Shenk, my friend and colleague, improved the manuscript with his painstaking edits and prudent advice. Numerous others offered support and escape along the way: Angella Baker, Hamilton Cain, Ruth Ann and Justin Castillo, Robin Diener and Terri Merz, Bill Fahey, Jan and Gordon Franz, Leslie Gordon, Leigh Haber, Allan Hill, LaVahn Hoh, David Hsiao, Michael Jacobs, Dominique Jando, Ben Kinningham, Ted Lee, Halcyon Liew and Arnold Horowitz, Evi Kelly-Lentz and John Lentz, Gordon Lucket, Chuck Meltzer, Irvin Mohler, Susan Moldow, Marcy Oppenheimer, Katherine and Will Philipp, Christopher Reohr, Karen Gulick and Max Stier, and last of all, David Duffy, who taught me how to juggle those many years ago.

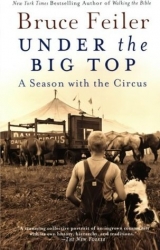

Finally, I would not have been able to run away and join anything for a year, or sit at home in front of my computer for a year after that, were it not for the unparalleled support team that surrounds me every day: Aleen Feiler; Mildred and Henry Meyer; Jane and Ed Feiler, editors, advisers, masters of more than one ring; and Cari Feiler Bender and Rodd Bender, newlyweds for now and a lifetime to come. Above all, I would like to express my increasing and undying gratitude to my brother, Andrew. He never set foot inside the ring, but he was outside it, alongside it, and even above it, capturing the circus with his unflinching eye. One of his photographs graces the back cover of this story and this book is dedicated to him.