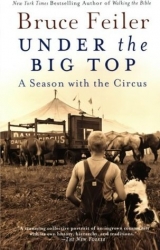

Текст книги "Under the Big Top: A Season with the Circus"

Автор книги: Bruce Feiler

Жанры:

Прочие приключения

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

This realization cut to the heart of the chief dilemma I felt about the show. In some ways our circus was a remarkably open-minded and tolerant place. Where else could people of such varying backgrounds—Mexican, Bulgarian, Moroccan, Native American, African American, Redneck American, not to mention Catholic, Jew, and Pentecostal, as well as drunkard, dope addict, missionary, teetotaler, carnivore, and anorexic—all work and live together in such an intense environment, two shows a day, seven days a week, six inches from their closest friend and their gravest enemy? On the other hand, many of the people in the show were remarkably bigoted. People’s actions were invariably attributed to their most distinguishing characteristic—race, religion, or waist size. The bookkeeper was good with money: he must be a Jew. Marcos made a misstatement: he must be a stupid Mexican. Admittedly, coming from the highly charged world of political correctness, I found this directness to be liberating. People on the circus don’t run around talking about others behind their backs: they do it right in front of their faces. While they are often uncaring and unsympathetic, at least they’re up-front about it.

Still this openness was not enough to balance my doubts, particularly about the macho climate that prevailed among the single men on the show.

“Don’t worry about it,” Sean said after Guillaume had left. “If you have to, you’ll just beat his face. He doesn’t attack me because he knows I’ll punch him in the nose.”

“But I’m not going to beat him up,” I said. “What will that prove?”

“It will prove you’re a man.”

As he was saying this, Guillaume appeared at the door. With Danny hovering over his shoulder and poking him in the back, Guillaume uttered a brief apology and the two of us shook hands. At that moment this simple gesture came as a great relief: some things I didn’t have to give up just to be a part of the show.

Jimmy was still in a bad mood from the gout. He was sitting behind the bandstand the following day in his hideaway ringmaster’s station when I arrived, as I usually did, just as the flying act was nearing its end, “the Flying Rodríguez Faaaamily…” As soon as he finished, he handed me the microphone and I sprinted toward the center ring.

When the stomach-pump gag started in DeLand it had a simple premise: various clowns dressed as sideshow performers would wander into a doctor’s office with a string of maladies, a doctor would put each patient into a giant stomach pump, and an assortment of funny objects would be exhumed from their bellies. An announcer would narrate the scene and give a name to each disease. Because of a feud between Elmo and Jimmy, I was chosen to be the announcer. “Hurry, hurry, hurry,” I would bark. “Step right up and see the circus sideshow…” In fact, I had to hurry myself in order to make it into the ring for the start of the gag. As I grabbed the microphone that second afternoon in Abington, I was a little behind schedule, arriving at the center ring just as the lights came up for the gag. At this point, with all eyes in the tent now focused on me since I was the only person in sight, I opened my mouth to begin my pitch when—twannggg—I suddenly collided face-first into a wire that was supporting the flying net. Crunch. The collision sent my feet into the air and my head crashing toward the ground. Dazed, all I could sense when I regained my wits was a booming outburst of laughter from the audience—the biggest I had gotten all year. Realizing I had made the fall of my life and satisfied that I still had my teeth in place, I hopped to my feet, did an Elvin-like style to make the fall seem well planned, and headed for the elephant tub in the center ring.

The next five minutes were the longest of my so-far short career. It took as much concentration as I could muster to narrate my way through the gag. When Arpeggio, who was playing the mad nurse, started to hound me, I tried to cut him off, but he jumped on me anyway, knocking off my hat for the second time in a minute and rendering me bald to the world.

At the end of the number I trotted back to the bandstand, handed Jimmy the microphone, and headed for a nearby fire truck to examine myself in the mirror. I was shocked: blood was streaming down my face from an open wound on my left cheek that ran from my eye to my upper lip. With all the red on my face perhaps the audience hadn’t noticed this. I hurried back to my trailer, took a swab of baby oil, and cleaned a path across my cheek where the wire had slashed my face. When I finished I lay back on my bed and nearly passed out from the ringing pain that stretched from my ear to the roots of my teeth. Then I waited for the rush of people who would want to see what was wrong. Nobody came. The second half of the show passed. Still nobody came. Finally, ten minutes after the close of the first show, Jimmy knocked on my door. I was still in my makeup except for the wound. My costume was strewn across the floor. I still expected to do the second show. Performers are relentless in teasing people who miss performances, especially for minor injuries. There’s plenty of pain on a circus lot, but little sympathy.

“Good God!” Jimmy exclaimed when he looked at my face. Glancing at my reflection in the window I saw that the previous shallow mark on my cheek had already swollen into a red puffy sore like a slice of slightly discolored peach on my otherwise pale white face. “Did you put ice on it?”

“It didn’t occur to me.” I was beginning to feel weak.

“Do you have any ice?”

“A few cubes, I think.” I sat down in my chair.

“Wait right here.”

Jimmy disappeared and returned moments later with a bag of ice and a tube of Betadine.

“First of all, get your makeup off,” he said. “You’re not going to perform tonight. Then put some ointment and this ice on your cut and get yourself to a doctor as soon as you can. I’ve got to go back and announce the second show. Do you think you’ll be all right?”

I assured him that I would be fine. After he left I carefully removed my remaining clown face, unplugged my camper from the generator, and just as the whistle blew for the start of the second show wobbled slowly off the lot and away from the tent.

“So, you’re a clown?” the doctor said to me as she entered the emergency room a little over an hour later. The ice pack was still on my face. Clown white was still behind my ears. I felt like a boy left behind in summer camp after the rest of my cabin had gone fishing.

“Yes,” I confirmed. “I’m a clown.”

“Well, then, make me laugh,” she said.

Why do so many people ask this question of clowns? I thought. Everywhere I went people asked for a free performance. If you want to be made to laugh, I felt like saying, come pay to see a show. She certainly wasn’t offering me free medical care.

My look managed to get the message across, and the doctor turned her attention to my face. After a brief examination she announced that I was at risk of developing an infection and if I didn’t take care of my wound it might require plastic surgery. Plastic surgery? I gulped. For a cut? Maybe I should have made her laugh. Yet she assured me that surgery wouldn’t be necessary if I followed her advice. “First,” she said, “I want you to go home and stand in the shower for thirty minutes and use this sponge to clean out your cut…” Now I truly had to laugh. If only she knew that I didn’t have thirty minutes’ worth of water in my Winnebago. “Next,” she continued, “let the shower water run over your face twice a day for the next three days. Water is the best cleansing agent.” Again I had to smile. The water that came out of my showerhead was hardly a good agent for cleansing anything. “Finally,” she said, “no makeup for a week.”

That would be the hardest of all.

“Were you fired?” Guillaume wondered when he saw me out of costume near the end of the second show. Everyone was surprised when I told them about the accident. They hadn’t seen it and, in the intervening two hours, hadn’t heard about it either. I was shocked. “You mean to tell me that, with all the worthless gossip that goes around this lot, when somebody actually gets injured nobody talks about it?” The performers know whom their neighbors are fighting with, flirting with, even fornicating with, but, it turns out, they know very little about what those neighbors are doing in the ring.

This seems only fitting. The American circus, I was beginning to realize, has developed its own standards of behavior unrelated to the larger world it inhabits. With these rhythms, of course, comes a code, a kind of artificial religion. In this religion the show itself is God. It’s unjudgmental, yet unforgiving. It rewards perseverance, yet accepts no excuses. Under its tent it expects allegiance, while outside its walls it doesn’t care. After four months I was just starting to appreciate the true dimensions of this world. Inside the ring I must act like a priest and spread the gospel of the circus, but after the show I could do as I pleased. On the surface this formula seemed simple enough. But as the show headed for New York City and the long sprint for home, I was unprepared for the wave of disenchantment that gripped our fold and the challenge that this would place on my ability to believe in the goodness of our cause. The season was far from over.

“Welcome to the beginning of the end,” Dawnita said a week later as I was preparing my camper for the drive from northern New Jersey into Queens.

“Any advice before leaving?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said. “Don’t go.”

Chuckling through my trepidation, I hopped in the driver’s seat of my Winnebago and headed alone for the George Washington Bridge.

Intermission

The Color of Popcorn

With the houselights illuminated for intermission the tent begins to stir. The clowns come pouring into the center ring to sign autographs; two elephants come plodding into ring one to give rides; and a dozen butchers come wandering down the track. The show is in recess, but the business marches on.

“Ladies and gentlemen, there will now be a precise fifteen-minute intermission…, with elephant rides in ring one—elephant rides for the entire family: you must purchase a ticket before boarding the pachyderm…concessionaires selling hot dogs, hot buttered popcorn, ice-cold Coca-Cola, peanuts, Cracker Jack, cotton candy, and delicious cherry Sno-Kones…plus—Mom, Dad, bring your camera, come right down to the center ring, and meet the clowns in an autograph party: don’t forget to purchase the all-new Clown Alley coloring book…”

The business makes quite a show.

As the circus inched its way back down the East Coast from New England toward its inevitable date with New York, it also moved steadily toward another important date: the change of leadership from Doug to Johnny. By early July, Johnny’s back had recuperated and he was preparing to rejoin the show. Before that could happen, Doug would have to chaperon the show’s twenty-seven trucks, thirty-five trailers, and two hundred employees to the door of the Big Apple. To date it had been an uneven ride.

When John W. Pugh and E. Douglas Holwadel first became partners in 1982, the two of them could not have been more different. Johnny, a boxy boater type at home on the high seas, was short and pugnacious, an English bulldog with a lovable face and occasionally vicious bite who was raised on the wilds of a circus back lot. He always smiled and never wore a tie. Doug, a self-proclaimed “dyed-in-the-wool Bob Taft Republican from Cincinnati, Ohio,” was tall and aloof, a Great Dane with an imperial mien and imposing strut who could roam golf courses and country clubs with ease but did not enjoy getting mud on his shoes. He never smiled and always wore a tie. He also understood money.

“As a kid in the 1930s I went to see the circus when it came to Ohio,” Doug recalled, “but unlike my friends, I wasn’t interested in the high wire or the flying trapeze, I was fascinated by the movement of the thing. Once my uncle took me to see them unload the railroad cars and I was hooked. From then on I became infatuated with the logistics—railroad cars, setups, tear-downs, things like that. Later that grew into a love of marketing.”

And what a marketer he became. When the two novice owners bought the circus, their principal step after redesigning the show was to rethink the marketing plan. Together they developed a new way for the circus to approach each town, a process they later termed the “true circus parade.” The first person in the parade is the booker, who, months or even years before the season, scopes out potential lots in a town and books the circus into a location. Terms are agreed on—usually the show pays about $500 to $1,000 a day—but no money is transferred. In many towns, the circus will then seek out a sponsor, a Rotary Club or high school band, which will agree to get all the necessary permits, licenses, and security personnel in return for about a third of the take. Still, no money changes hands.

Next, two months before the show arrives, a media buyer visits the town to book television, radio, and newspaper advertising. He is followed by a marketing director, who actually lives in the town for up to a month, schmoozing the local media, ordering hay and feed, and trying to generate publicity about the show. Some of the advance purchases are paid for with IOUs, far more are bartered for with complimentary tickets. Thus, if the front end has done its job, by the time the red arrows leading to the lot are posted and the stake line is laid out, the circus has generated thousands of advance sales but still not spent any money. The actual cash doesn’t arrive until the show does. When that happens lots of people smell it out.

A century ago, whenever a circus arrived in a town the sheriff would remove the central nut from one of the wheels of the show’s main wagon to make sure the circus couldn’t leave town until its bills were paid. Ever since, the term “making the nut” on a circus lot has implied taking in enough money to cover expenses. On our show the nut was around $25,000 a day (roughly $6 million in yearly operating expenses divided by 240 show days). That meant the show had to sell enough six-and nine-dollar tickets as well as enough one-, two-, or four-dollar concessions to earn $25,000 every day—rain or shine, ice or heat. The expenses were relentless. There was a $50,000-a-week payroll, a $3,000-a-week fuel bill, and a $500 added charge every time the circus played a mall in order to pay a local contractor to visit the parking lot after we left and fill in all 476 stake holes left behind by the tent. In addition, every week the show bought an average of three hundred pork chops, eighty pounds of ham, sixty pounds of sausage, ninety dozen eggs, thirty gallons of milk, and fifty pounds of coffee, not to mention five hundred pounds of oats, seven tons of hay, and a quarter ton of sweet feed.

Of course, there were all sorts of unexpected costs as well. A weigh station outside Burke, Virginia, for example, cost the show a small fortune. Three trucks—the horses, bears, and cookhouse—each received fines of $260 for not keeping their logbooks up to date. The cookhouse was fined an additional $1,000 for having a passenger in the cab with an open beer can in his hand.

All of this money—for food, fines, and weekly salaries—was paid out in cash. Some local vendors felt so uncomfortable receiving their fees in cash that they came to pick up their payments with armed guards in tow. I could understand their apprehension. Never in my life had I seen so much money. During a good engagement the show could take in close to $100,000. At certain times of the year there was probably close to a quarter of a million dollars locked in the safe in the office truck, stuffed under mattresses in performers’ trailers, and tucked under Q-tip boxes in the clowns’ trunks. All cash. Much of it in small bills. Most of it untraceable. Since many of the people on the lot were often broke, or had very limited resources, just the knowledge that all this money was floating around prompted some pretty sordid behavior. The money was like an unspoken curse tempting people to misbehave.

Those who lacked it were desperate to get it. Workers, for example, regularly hounded performers for money. One went so far as to steal money from one of the clowns while we were doing the firehouse gag. Another, more innovative, purchased a metal detector and staked out dibs to be the first person to search under the seats after each performance. Those who had it, meanwhile, were desperate to stretch it. One senior staff member, realizing the need workers had for cash, offered to pay an advance to every worker on the Wednesday before payday. He would give them seventy-five cents for every dollar of their paycheck, then claim the full dollar for himself from their salaries five days later. In the Middle Ages, this noncompounded annual interest rate of 1,300 percent would probably have made usury the eighth deadly sin.

Still, one of the things that amazed me most about the circus was how these workers—who by the time they took their draws might make only fifty dollars a week—could live in complete harmony within inches of the show’s owners—who in a good year could split nearly a million dollars in profit. In stationary America, fences, guardhouses, zoning laws, and approval boards usually make sure there’s a greater distance between the haves and the have-nots. Without these barriers, the owners were almost compelled to be generous with their money, if for no other reason than to preserve the loyalty of their workers and the safety of their possessions. In the first half of the year alone Doug personally loaned out close to $25,000 to various people on the show, including $12,000 for Michelle and Angel Quiros to buy a new truck when the one they had purchased from a Pentecostal friend in Florida broke down during its second month on the road. The couple was teary-eyed with gratitude. “No other owner in the world would do that,” they sobbed. “Anyone else would have fired us on the spot.”

For all the equilibrium on the lot, however, and for all the profits the show was making in the first half of the year ($153,000 in April alone, twice as much as the year before in the midst of a recession), Doug could still rarely manage a smile. First he had the problem of dispersing all that cash. Most banks will not accept large deposits of cash from out-of-towners, he noted, because they have to report every transaction involving over $10,000. The process became even trickier in the early 1980s, he said, when Florida banks were accused of laundering money from drug dealers. Even today Doug and Johnny receive an average of one or two calls a year from people seeking to launder money. Instead, they take the equally risky approach of driving long distances with hundreds of thousands of dollars in small bills. Like political correctness, gender equality, and racial tolerance, the much-heralded cashless society has yet to reach the circus.

The second and much more serious problem Doug faced was the skyrocketing cost of protecting the show. In 1983 the Clyde Beatty-Cole Bros. Circus paid a total of $80,000 for insurance. Ten years later that figure had ballooned to just under half a million—over $200,000 for trucks and general liability, and an equal amount for workers’ compensation. In the weeks leading up to his leaving the show, Doug spent much of his time trying to renegotiate these rates. The show had produced only $50,000 in claims in recent years, he argued, surely his rates were exorbitant. Safety was up, he asserted, risks were down. By late May he thought he had a breakthrough when suddenly the show was battered by a series of mishaps—Danny fell from the swing, Henry chipped his teeth, Big Pablo was told he needed knee surgery—followed by a series of freak accidents—man killed by an elephant, woman slashed by a bear, worker drowned in a pond. “We are not liable for these incidents with the animals,” Doug said, “especially the one in Fishkill. But when you bring ten elephants into a small town you make a pretty big target.”

By early July, when Doug was ready to leave, business was up, but morale was down. The show was ready for its old captain at the helm. On the morning of July 4, Doug hopped into his maroon Cadillac with the EDH plates and headed south down I-95. The same day Johnny arrived in his matching white Cadillac with BIG TOP on the plate. The show breathed a collective sigh of relief. Little did anyone realize, however, that within a week the show would have its first genuine financial crisis of the year.

KEEP OUT THE CLOWNS, blared the headline in Newsday on Thursday, July 15. ISLIP BARS CIRCUS, CITING COMPLAINTS.

The news from Long Island stunned the show. In the nine-month season of the Clyde Beatty-Cole Bros. Circus the seven weeks the show spent in New York were considered the highlight of the season, a core stretch of dates when business was usually good enough and the crowds generally enthusiastic enough to make up for the grit and grind of the City. The New York engagement was also the pearl of Doug and Johnny’s revived marketing strategy. The circus didn’t merely play New York City, it played the City’s parks. The invitation came about after years of intensive lobbying of the Parks and Recreation Department. As soon as a creative profit-sharing agreement was reached, the show moved first to Forest Park, then to Shea Stadium, Staten Island, and the Bronx, and finally this year into Marine Park in Brooklyn, a grassy lot off Flatbush Avenue not far from Coney Island. Business overflowed in most of these areas, but the red tape was nearly overwhelming.

In most towns along the route the show would pay around fifty dollars for a building permit and maybe twenty-five dollars for a health inspection. Police and fire departments were usually willing to provide complimentary protection just so their members could stand in the wings and watch the show for free. In New York nothing was free. In fact, the circus was forced to pay more than $2,000 a lot in surcharges: $200 for building permits; $100 for food handlers’ permits; $250 for fire guard licenses; and $1,500 for fire permits covering the tent, the welding machines, the generators, the truck repair shop, and the two carbonic drink dispensers. To make sure these rules were followed, an inspector sat in the front of every show taking notes like a court stenographer. “In the past we used to resort to bribery,” Johnny recalled almost fondly. “The fire inspector would come on the lot and say, ‘I sure would like to bring my family to the show.’ We’d give him some tickets; he’d sign the sheet and leave. These days we can’t do that anymore. If they don’t like that and want to cause trouble, I’ll just follow them all over the tent and agree to the changes they suggest. They’ll usually tire of the process and leave.”

Sometimes, however, they don’t. Early on in the show’s stay in New York one fire marshal was so peeved that he decided to shadow the ringmaster throughout the performance. “It was awful,” Jimmy recalled. “He was standing next to me and between every act he would slap me on the shoulder and say, ‘Make another no-smoking announcement.’ Finally, after about ten no-smoking announcements I got so sick of listening to the man that I turned to him and said, ‘Go fuck yourself!’ You can imagine what happened. He stormed off in a huff and went looking for one of the managers. The one he found was napping in his trailer. The fire marshal pounded on the manager’s door, waking him from his sleep. ‘Sir, your announcer just told me to go fuck myself.’ ‘Well, what do you need from me?’ the manager shouted. ‘Directions?!’”

Despite occasional breakdowns like this, the aboveboard bribes that the City demanded hardly hurt the circus’s bottom line. As soon as we hit New York the show stopped its policy of giving out discount coupons; it added a third show on Sunday evenings (though salaries were not increased); and it raised ticket prices by a dollar. Still we couldn’t keep people away. In Marine Park the community was so overjoyed that a circus would venture into its isolated neighborhood that families thronged the lot at all hours of the day and we turned back nearly a thousand people every night. All fears that New Yorkers would be hostile and cynical were, for the moment, laid to rest. In fact, several days after we left the City the following letter appeared in the Daily News:

CAN’T (BIG) TOP THIS

Ladies and gentlemen and children of all ages, I witnessed a miracle in Brooklyn! I saw families sitting together, laughing, having good clean fun—no violence, no nudity, no dirty language. Where was this rare occurrence? At the circus in Marine Park. A

big

thank you to the Clyde Beatty-Cole Bros. Circus and N.Y.C. Department of Parks and Recreation.

E. Francis

The show was still savoring this unexpected bouquet when the bombshell arrived from Long Island.

“Where does a two-ton elephant sit?” quipped Newsday in the opening line of its article about the circus being banned. “Anywhere it wants to—except Islip.” The article went on to report that the Islip Town Board had voted 4-1 to deny a permit to the circus “based on pressure from animal rights activists and a recent incident where a man was killed in a freak accident at the circus.” “Animal lovers have come out of the woodwork,” said the town clerk, whose office received a reported one hundred letters and thirty phone calls protesting the show’s alleged cruelty to animals. Complaints included inadequate food and the use of cattle prods, the report said. Also, protesters cited the incident in Fishkill as proof that animals are potentially dangerous. “God forbid [the elephants] should break loose here,” one board member was quoted as saying. “About fifteen years ago at a Republican parade here, an elephant was scared by a car that backfired. It broke loose and trampled the car.” The one dissenting vote came from a member who said stories of animal abuse are “greatly exaggerated,” much like the story of the Islip elephant. “Every time I hear that story the elephant gets bigger,” he reportedly said.

By the time the news arrived on the lot the elephant had gotten even bigger and the impact even larger. Johnny Pugh was irate. Meltdowns this serious weren’t supposed to happen on two weeks’ notice, especially on Long Island. Johnny had even hired a fixer for the area, a man with widely touted connections, who was supposed to escort the show effortlessly through its three-week stay on the Island—a place with well-known political and family rivalries. Now the system had broken down. In the days after the incident was first reported the details became clearer. Johnny believed that one particular animal rights activist from Islip was behind the circus being canceled. She had been bothering the show for years, he said. This year she demanded that she be allowed to speak before zoning boards in Commack and Yaphank. In Commack she was denied because the flea market where the circus plays is zoned for circuses. In Yaphank she reportedly stood up and read for twenty-five minutes from Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Stories.

“Listen, I’m concerned about animal rights, too,” Johnny griped. “Hell, my wife spends a lot of time running after stray cats and dogs. But this is going too far. When I was a child I used to have an original copy of Kipling with gold on the pages and a piece of tissue paper over every drawing. I wish I’d never given it away. Maybe that would show them I care.”

At this stage it probably wouldn’t do much good. The debate itself had already become part of the absurd theater of American political life, with each side posturing, sloganeering, and even threatening legal action over the other’s head. In one corner were the protesters. “We welcome the clowns and acrobats,” one mother in Islip had said in the meeting, “but please spare us and our precious children the spectacle of animal torment.” In the other corner was the circus. Johnny and Doug told their lawyer to consider bringing suit against the organizers for slandering the circus, disrupting business, and generally being a nuisance. In the middle were the politicians. Worried it might have failed to give the show due process, the town of Islip began bending over backward to appease the circus. The media, of course, were all over the story. Radio stations in the area began blasting the town board, especially after they learned that proceeds from the show’s three-day run were to benefit the Talented Handicapped Artists Workshop, known as THAW. Several lawyers in the area who regularly took their children to the circus went so far as to contact the show and offer to sponsor a class-action lawsuit against the town. The circus is supposed to bring its own entertainment to town, but with bumbling local officials, grandstanding lawyers, bleeding-heart protesters, and heroic handicapped artists, the cancellation of the circus brought out a far more interesting sideshow of modern American freaks and gold diggers. The publicity was priceless.

“We didn’t want it to happen this way,” Johnny said after he extended our stay in Staten Island for three days and then booked the same lot in Islip for the following year. “But in the end this case may bring us more good than harm. The truth is, I’d hate to see the animals disappear. Look at the audience. When they think of circuses, they think of animals. They can see acrobatics or gymnastics on television. They can see sports anywhere they want. But they have no chance to see trained animals. Even the ones at the zoo don’t do anything. That’s why they come to the circus, and that’s what they remember when they go home. A circus without animals is just not a circus.”

For all his breathless enthusiasm, Johnny knew those days might soon be over. Animal acts, like the circus itself, are being pressured out of business. Human acts, even the interesting ones, can hardly fill the void. People are much less reliable than animals…and much harder to control.