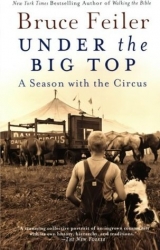

Текст книги "Under the Big Top: A Season with the Circus"

Автор книги: Bruce Feiler

Жанры:

Прочие приключения

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Reeling, none of us left the lot that night. I, like many, went to bed early. The circus seemed so unforgiving. The dream seemed out of control.

Where Are the Clowns?

Just in time the clowns arrive.

Walking now instead of running, I approach the center ring with Jimmy’s microphone just as the Flying Rodríguez Family completes its final style. As they exit, Big Pablo tries to knock off my hat. Little Pablo feints a right hook to my face. The camaraderie gives way to a gulp of loneliness as I hop on top of the red elephant tub and spin around in my oversized shoes. For a second the tent is tense with silence. I’m all alone in the center ring. Jimmy blows his whistle from behind the back door and the voice that fills the tent is mine. I’m master of the moment. I’m lord of the ring. I’m a child again.

“Hurry, hurry, hurry…”

At the beginning of the year the sound of my own voice startled me. Blaring from the speakers and hurling through the air, it was painfully shrill—and way too fast. I couldn’t hold the squirming crowd. I couldn’t hold the silly accent I’d adopted for the part. I couldn’t even hold the microphone, I was shaking so hard. Elmo advised me to drop my accent, lower my voice, and speak into the microphone as if I was talking to a room full of children.

“Step right up, boys and girls, and see the circus sideshow…”

Within a few days I had slowed myself down, and within a few weeks I had deepened my tone in an attempt to mimic the full-bodied bass that Jimmy used so well. A former clown himself, Jimmy had a way of hanging on certain vowels and soaring with certain syllables (“The Flying Rodríguez Faaaamily…”) that gave his otherwise flat-footed phrases the ability to turn somersaults in the air. It was by listening to him over several months that I learned the central lesson of announcing, indeed the central lesson of clowning itself. The key was not to be myself, per se, but to be my clown. This notion, so simple, was surprisingly difficult to comprehend, though it ultimately proved pivotal to my ability to perform. It freed me from any embarrassment I might otherwise suffer from standing around in silly shoes with a pointy cap on my head. It allowed me to transcend my otherwise critical mind and act on behalf of my instincts. Above all, it empowered me to override my superego—the constraints learned from society—and live according to my id—my deepest, childlike urges.

This is the genius of clowns, and for some reason only children fully understand it. An adult looks at a clown and sees a person in makeup. A child looks at a clown and sees something else entirely—a caricature, a cartoon, an invincible creation doing what that child always wanted to do: being silly and not being reprimanded, being reckless and not being injured, being naughty and not being punished. Not surprisingly, the child is right. The makeup, so central to the adults, is not an end unto itself; it’s a means of escape. It’s a two-way mirror: allowing you to see what’s deep inside of me, and allowing me to reflect what’s deep inside of you. I was not myself in the ring. I was you. I was everybody. I was a clown.

“Here he is, ladies and gentlemen, the world-famous fire-eater—Captain Blaaaze…”

At the moment, however, I am king of the roost, a sideshow barker with a straw hat and a sassy attitude. As I start my pitch, Henry comes stumbling into the center ring, flinging behind him a Superman-like cape and waving in front of him a fiery torch. He staggers up to the elephant tub, and just as I’m about to brag about his “amazing feats of fire consumption…,” he points to his stomach, groans in pain, and collapses onto the ground.

“Uh-oh, boys and girls! Captain Blaze can’t work tonight. Heeee’s got a stomachache. What are we going to do!? Is there a doctor in the house…?!?”

The words are barely out of my mouth before a screech comes from the back of the seats, the band converts to an upbeat romp, and Marty comes speeding into the ring with flaming red hair, a long lab coat, and a four-foot stethoscope. With his manic pace and agitated action he looks like an absentminded physician—Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. He is followed closely by Arpeggio, wearing mud boots, a nurse’s cap, and a giant white dress that sticks out two feet from his bust and butt with oversized foam vital parts. The Playboy Bunny meets Florence Nightingale.

“Boys and girls, please welcome…Dr. I. Killum and Nurse Anna Septic…”

Stopping briefly to accept their accolades (Anna just can’t resist applause; at one point she actually shoves aside the doctor to blow a kiss to her fans), the two professionals from Clown Town Hospital lift the patient off the ground and carry him to a two-piece stomach pump that is waiting in ring one. After a giant suction cup is attached to the fire-eater’s stomach, the procedure is ready to continue.

“Boys and girls, we need your help…, help us count to three…!”

Standing at the front of the pump, a giant wooden box about the size of a washing machine, the nurse grabs the handle and pushes toward the ground.

“One.”

With each push on the bar she sticks out her butt and the patient’s limbs go flailing.

“Two.”

Until her final hefty push when the crowd has joined the call.

“Three.”

At which point the doctor goes to the machine and reaches into its core.

“Doctor, Doctor, what was the problem…?”

He pulls out a giant gasoline can and squeezes his nose in disgust.

“Too much gas…!”

The audience groans as the pun settles in. The next patient staggers to the door.

Since opening day the stomach-pump gag seemed to epitomize all the internal rhythms of Clown Alley. At the beginning of the year the gag was a source of constant friction. Elmo had designed the routine to be what he called a “big bang” gag. “You go through a bunch of business, the object goes bang, and a big surprise pops out.” As he saw it, the gag starts gradually, with each bit getting progressively funnier, until the big surprise at the end. “There’s a rhythm to the gag,” he explained. “You have to have three or four bits so the audience understands the routine.” Jimmy, however, didn’t like rhythm gags; he liked sight comedy—quick visual bits with immediate payoff. Caught in the middle, the clowns didn’t much care about either theory. All we wanted was laughs, which the original gag wasn’t getting. We set out making changes. First, the announcer was moved closer to the action. Next, the number of patients was reduced. Finally, the ailments that afflicted the patients were piqued to make the jokes punchier. By the time we reached New York the gag had been nearly halved in time and more than doubled in laughs. The playpen had performed successful group therapy.

Other changes in the Alley were evident as well. The early tension over my presence had given way first to begrudging admission that I was actually doing the show every day and then by the summer to a surprising brand of acceptance. One incident in particular epitomized the new atmosphere. After autograph party one night in Queens, I stopped by the side of the tent to speak with Khris Allen, who had come to discuss where we were having dinner after the show. As we were speaking, a woman in blue jeans with two small children started badgering me. “Hey, clown!” she shouted from her seat. “Come speak with my children.” When I signaled that the second half was about to begin, her requests became more blunt. “What are you doing?” she blared. “Stop talking to that man and come talk with us.” When I didn’t respond she stood up and started yelling. “Hey, you sorry-ass clown. Come over here and talk to my kids. That’s what you’re paid for. Entertain us!” I left without turning her way.

Back in the Alley when I described this outburst, the other clowns decided to seek retribution. During the stomach pump that evening, Marty, who was playing the fat lady, went to the woman’s side during the act and started dousing her with popcorn. At first she thought it was funny, until the popcorn didn’t stop. One handful in her face. Two handfuls at her mouth. And when she raised her arm to protest, another handful down her blouse. “We clowns have to stick together,” he said when it was over, and this time his slogan had more meaning. The change was showing in our work.

Almost shouting now, I call toward ring one.

“Wait, Doctor, you’re not through yet…, here comes another patient…”

As soon as I speak, four-foot-seven-inch Jerry steps into the ring.

“It’s the circus short man…”

Pointing desperately at his stomach, Jerry staggers in the direction of the nurse and collapses in her arms.

“Looks like he’s got a stomachache, too, Doctor. What are we going to do…?”

The doctor leads the short man to the examining table as the nurse heads toward the pump.

“Now, boys and girls, we’re going to pump his stomach…Are you ready to count?”

The children wriggle with anticipation. I raise my arm in the air.

“One.”

This time the count begins much louder. The doctor encourages the roar.

“Two.”

The entire audience enters the game. The nurse is primping her hair.

“Three.”

Until all eyes inside the tent are looking directly at the machine.

“Doctor, Doctor, what was the problem…?”

Marty reaches into the pump and withdraws a metal pie plate piled high with shaving cream. The audience coos in expectation.

“Look at that, boys and girls.” The doctor sneaks up behind the short man—“Too…”—lifts the pie above his head—“much…”—and steadies his arm for the final blow—“SHORTCAKE!”

Splat.

As soon as the words come out of my mouth Marty takes the plate of cream and smashes it into Jerry’s clown face. The timing couldn’t be more perfect. The audience couldn’t be more thrilled. We clowns are working as well together as we have worked all year. Meanwhile the performers all around us are viciously tearing themselves apart.

By August I had a hard time remembering my early days on the show—the sense of excitement, the feeling of wonder, the idea that around every corner was an undiscovered dream. These impressions had been replaced with an almost oppressive feeling of familiarity with the circus, and with it a sense of isolation from the outside world. Various things marked this transition. At the start of the year the number of trucks and trailers on the show seemed too many to count; now on any highway in the middle of the night I could identify any vehicle by the shape of its taillights alone. At the beginning of the season the sheer volume of costumes was almost overwhelming; now I could pick up any spangle on the lot and identify whose costume it fell off of. On opening day I carried a watch and nervously counted the minutes between acts; now I no longer looked at the time but listened to the music instead. More than merely joining the circus, I had completely melted into the show.

To be sure, living in such an intimate community has its advantages. It’s cozy, for one. There’s a certain comfort that comes from living and working so closely with people, a kind of unspoken trust that comes from constant contact with your neighbors and from an encyclopedic knowledge of their most intimate noises. If nothing else, I had complete faith that after six months in this world everyone in the circus would defend me to the death from the threat of outside force. Circus people may tear themselves apart, but to the outside world they present a resolutely unified face.

Still, if this world felt so safe so much of the time, why did it seem so perilous to inhabit? Why did people flee in the middle of the night? The answer, I came to feel, exists in the nature of the melting pot itself. With such a wide variety of ingredients, the only way for this kind of community to thrive is by letting each individual component live according to his or her own rules. The circus, as a result, is fundamentally liberal. Its essence is its freedom. Its peril is its license. In this way, more than most, the circus is a startling mirror of America, presenting an image that is either a precise reflection or a gross exaggeration. Either way, it’s definitely a world where bodies are primal, where people work with, express themselves through, and spend a remarkable amount of their leisure time worrying about their physical selves. And what about their minds? Some pray. Some read. Some sing. But many more watch Geraldo, read the Enquirer (that’s how Kris Kristo, for one, learned English), and talk about their neighbors.

Above all, it was this lethal strain of gossip that so soured me. The sudden departure of Danny Rodríguez brought forth a seemingly endless stream of accusations and innuendo. This wasn’t the tame sort of gossip about who got pregnant before they were married or who was knocking on whose trailer last night. Instead it was a more venomous breed, designed to weaken and destroy. When I first joined the show I was fascinated by all the tales of family intrigue around the lot. I was curious about the number of angles, affairs, and character assassinations that could be flown around one group of people. By August I was sick of them. Did I really want to know that a man I like, a man I admire, tried to make a pass at his own son’s wife? Did I really want to know that another man I like, a man I respect, is married to two women at one time? These activities may be part of “real life,” but if they are, then I know why people go to the circus, for their real lives are too much to bear.

“I knew this was going to happen,” Jimmy James berated me when I told him about my frustration. “You’ve gotten too close. You’ve been at the fair too long. You can’t get attached to these people. You can’t think you’re doing it for them. You’re doing this, we’re all doing this, for the ring. For the love of the circus. It’s like a day-care center all around this lot. That’s why I just retire to my trailer after the show and pull my curtains down. You can’t let circus life ruin your love for the circus.”

After thirty years of living in the same day-care center, Jimmy had tapped into one of the few consistent veins that joined people on the show: the only way to survive in the circus was to build a private world of one’s own. Circus people, I realized, are like tigers: they have a tendency to devour their own. Those who survive do so by living in a tiny cage and only coming out when they have to perform. Right down the line of performers—Nellie and Kristo Ivanov; Venko and Inna Lilov; Dawnita and Gloria Bale—each of these people told me at one time that the only way they survived in the circus was by minding only their own business and nobody else’s. They survived by reaching some mysterious vigilante nirvana, where they trusted no one else and worried only about themselves. They had their forty acres and a mule. They were free.

This is America, I thought to myself. It is the circus. Could I find my way home?

Beaming in my artificial smile, I stand in the middle of the center ring and prepare for the blowoff of the gag.

“Okay, Doctor, you’ve fixed two, but look who’s coming now…” I point my glove toward the side door of the tent, where Rob appears in a flowery dress (with an inner tube hidden underneath it) and a tub of popcorn and a drumstick in his arms. “It’s the circus fat lady…”

The children giggle at the beastly sight. The fat lady stumbles into ring one, gestures toward her giant stomach, and collides, with an accompanying tympani crash, into the equally obese Nurse Anna Septic.

“Uh-oh, Doctor. She’s got a big, fat stomachache…”

The nurse leads the fat lady to the examining table and with a certain degree of huffing and puffing finally attaches the suction cup to her stomach.

“Now, boys and girls, you better count loudly, she’s got a big stomach…”

The nurse hurries over to the lever of the pump and most of the children rise to their feet.

“One!”

Their voices are so enthusiastic they rattle the rancor inside my head.

“Two!”

They want so much to believe in the clowns it would be a shame to let them down.

“Three!”

At the end of the count the fat lady stands up and the doctor hurries to the pump. The machine, however, is overheating—coughing and shaking, about to explode. Retrieving a rope from inside the machine, the doctor beckons the fire-eater, the fat lady, the short man, and the nurse to help him pull out the offending object.

“Doctor, Doctor, what was the problem…?”

The crew prepares to do battle with the machine.

“Too much…” They make one collective pull of the rope. “Too much”

They make a second tug together. “Too much…” And on the third yank of the rope the line of clowns falls back on the ground and—kaboom!—a giant, eight-foot rubber chicken comes bursting through the doors. “Friiiiited chicken!”

Ugh.

Despite this blowoff that was never quite funny, the chicken flaps his wings in the ring as the children clap their hands in amazement. The clowns, in the end, have done their job. We have distracted the audience long enough for the flying net to come down and the elephants to move into place.

Indeed, trotting back to return the microphone, I couldn’t help feeling on more days than not that being a clown is in essence being a distraction. Not only did I see it work every day on hundreds of children and their parents. I saw it work every day on me. Even in the depths of my despair about the circus I never stopped painting a smile on my face and transforming myself from a grump to a clown. The transformation wasn’t voluntary. In fact, just when I was ready to cast off my vision of the circus as a childish delusion, a young boy named Justin came running up to me after the stomach pump in Yaphank, Long Island, and asked if I would autograph his program. Hundreds of other children had asked me this in the preceding five months. But on this day—two weeks after Buck had left; one week after Danny had left; on a day when I thought I might want to leave myself—I picked up Justin’s book and signed my name, “Ruff Draft,” and the simple act seemed like a rare gift. Justin took his book back and beamed a distinctly nonartificial smile. Then he stepped forward and embraced my knees.

11

Reborn

“I felt light, like somebody was lifting my soul. The water went rushing over my body. The white gown got wet and stuck to my skin. I could feel myself transform…”

Sean Thomas was lying on his newly purchased mauve sheets staring up at the ceiling in the back of his trailer. Dressed in tan shorts and white athletic socks, he looked uncommonly crisp and clean, like a child fresh from a bath. The Mighty Mouse above his left nipple was pink from the shower. It was just after eleven on Saturday night in Toms River, New Jersey, and the show was tucked in for the night behind St. Andrew’s United Methodist Church just off the Garden State Parkway. Talk of God was in the air: Reverend Mark Fieger, the local pastor, was planning Sunday-morning services for the center ring. The Lord works in mysterious ways: Father Jack, the regular circus priest, was forced to hold mass in the cookhouse. Sean, meanwhile, had seen the light.

“The truth is, I owe it all to Jenny,” he said. “If not for her I wouldn’t have gone.”

“That Jenny,” I said. “She must be magic.”

“I don’t know about that,” he said. “All I know is, she’s my wife.”

When Sean hit the ground he switched direction. His new course took flight surprisingly fast.

“I remember the first time I saw her.” he said. “She came to see show in Florida at the end of last year. She was dressed real plain on account of her religion. She had no makeup on and was wearing a long dress. But she had these pretty green eyes and a killer smile. ‘Kris,’ I said, ‘who’s that?’ ‘That’s Jenny Montoya,’ he said. ‘She does a flying act.’ I asked him to introduce me to her. ‘Okay,’ he said. ‘But I’ve gotta warn you. She won’t sleep with you unless you marry her.’

“We started talking,” Sean remembered. “At first it was mostly about her old boyfriend and stuff. There was this guy from town who she was engaged to, but she had to break it off. He wanted her to go to college, but she told him she had to go back on the road. He thought about joining the circus, but it wasn’t really for him. Eventually they split up. I told her I had had a girlfriend, too, and basically the same thing happened. Sometimes you just can’t call from the road. Sometimes you can’t call for months. Jenny and I were talking about all these things, and the more we talked, the more we had in common. I swear we were like the same people.”

The next day Jenny came to the show again.

“I knew she was there but I didn’t say anything to her,” Sean said. “Later I was walking off the lot after the show when I heard somebody say, ‘Sean.’ I looked around and it was Jenny. ‘Hi,’ she said. ‘I want you to meet my pastor.’ I couldn’t believe it. I hadn’t even met her mom and dad. I knew something was going to happen…”

For the moment, however, nothing did. For the next three months they didn’t see each other, and when they met again in Louisville during a pre-season gig for another circus, Sean completely ignored her. “Blew her off, cold,” he said. “This was my first time on a different show. There were lots of girls. Still, I always had my eye on her. I would see what she was doing, who she was with. She was always alone or with her parents. I just kept my thoughts to myself.”

The season began for Beatty—Cole and another four months passed. The two of them were out of touch. Sean never mentioned Jenny around the lot, but his primping and nesting around his trailer belied his distraction. None of us knew why, until we reached New York. At the time there was a sudden flurry of activity. Nearly half a dozen shows were in the area, and every night performers went hurrying to see their friends on other circuses or hosted small reunions around our tent. It was in this stir that Jenny reappeared. She was quiet, shyly beautiful, and blended right in. Like most circus people, she was related to many of the performers on our show. Also she was best friends with Michelle Quiros. Nobody thought anything about her visit. Nobody, that is, except Sean.

“For a week every time I came out of the tent I would run into her. We would talk. The truth is, I made a point of talking to her, We would talk. The truth is, I made a point of talking to her, and she did the same with me. We just talked. Nothing more. I didn’t even make a move. One night we were sitting in front of the horses talking and her brother came walking by and said something to her in Spanish. She started crying.

“‘What’s wrong?’ I asked her.

“‘My brother called me a tramp.’

“‘Why?’ I said. ‘Because you’re talking to me?’

“‘Because he’s jealous,’ she said.

“‘What for?’

“‘You know my brother…,’ she said. ‘He’s jealous because I’m with you.’ Then she started laughing.

“‘No shit,’ I said. ‘You mean you people are fighting over me?’

“‘I guess so, but it’s still bad for me to be talking to you all the time. People will think. You know how the circus is….’ For a week she didn’t come back. I thought she had given in to the pressure. That’s when I hit the ground.”

In the wake of his accident on Staten Island, Sean was a different man. Isolated because of the fight, he was mostly left alone. In pain after every shot, he became surprisingly self-restrained. For the first time since he joined the circus he had been rebuffed—by his body, by his friends, and, apparently, by a girl.

Jenny, it turns out, was in a similar plight. After the incident with her brother, she got into a fight with her parents. She was twenty-three years old, she said. She ought to be able to talk with anybody she wished. Sean had encouraged her to stand up to her family. Now, having done it, she felt all alone. Finally, in a gloom, she decided to flee. With the aid of a friend she jumped into a borrowed car and drove the length of Long Island overnight to the tiny seaside town of Greenport, where the world’s largest tented circus was playing a one-day stand.

She couldn’t have picked a worse day. The lot was dusty, behind an abandoned warehouse. The circus was ornery, Danny had just left. And to make matters worse, word had just reached the lot that Elmo—on an advance publicity tour for the show—had thrown a fit at a mall in Glen Burnie, Maryland, tossing his makeup into a fountain, smearing black greasepaint on a photographer’s bald head, and quitting the show in a late-summer huff that seemed to prove that no one was immune to the back side of the circus pendulum. It was hardly the right atmosphere for a confrontation, but at this stage one could hardly be avoided. Jenny’s parents, realizing what she had done, hopped in a car themselves the following morning and headed out in pursuit. The circus would have a rival show that night, just at the time that Billy Joel was said to be bringing his children to the circus.

Jenny arrived just as the first show was ending.

“I saw her step out of the car,” Sean recalled, “and I could see the tension on her face. She tried to avoid me and go straight to Michelle’s, but the high wire was working and nobody was home. Finally she came over to the cannon. ‘Man, you just need to get away from your parents,’ I told her. ‘They’re driving you crazy. You can’t do anything. They’re treating you like a child.’

“‘I know,’ she said. ‘I’m not happy. But there’s no way I can leave. I have no place to go.’

“‘Sure there is,’ I said. ‘You can come with me.’”

“‘I can’t go unless I get married,’ she said.

“‘Well then,’ I said, ‘let’s get married.’”

“Ladies and gentlemen, our featured attraction, the World’s Largest Cannon…!”

The ringmaster’s voice interrupted the scene. With Jenny left standing at the altar, Sean excused himself to go do his act. By the time he returned Jenny’s mother had arrived. “‘Sean,’ Jenny said, ‘I want you to meet my mother.’” Sean went over and shook her hand. Jenny’s father was parking the car. “‘Mom,’ Jenny said, ‘Sean wants to marry me.’

“‘That’s right,’ I said. ‘I love your daughter.’

“‘That’s good,’ her mother said. ‘That is very good. But what about my husband?’

“‘I’ll tell him,’ I said. ‘I don’t care. Let’s go tell him now…’

“‘No,’ Jenny said. ‘No, we can’t. I’m afraid.’”

The second show started. Jenny went to find her father. During intermission she reappeared.

“‘Guess what?’ Jenny said. ‘My mom told my dad.’

“‘And…’

“‘He said he likes you. He said you’re a decent man. You’re clean. You shave good.’”

Shaving? For months Jenny’s father had been observing Sean. In Florida he had seen the act. In Louisville they had shared a dressing room. In Greenport, finally, they met face-to-face.

“I went to see him after the show,” Sean said. “He was standing by himself. ‘I love your daughter very much,’ I said. ‘I want to marry her.’

“‘Sean,’ he said without hesitation. ‘I want you to know. This is the happiest day of my life.’”

Two days later Sean Thomas Clougherty and Jenny Montoya were married in a private ceremony near Yaphank, Long Island. That day he twice got shot out of the cannon.

“The funny thing was, I never even held her hand until I asked her to marry me,” Sean said. “I never even kissed her until we were engaged.”

“So in the end, Kris was right,” I said.

“But I wanted it like that. I wanted it to be all new with the girl I married.”

“You’re just an old-fashioned romantic after all.”

“I guess you could say that.”

“So why do you think her parents were so happy?”

“Because I’m a good guy.”

“No, you’re not,” I said. “You’re a jerk.”

Sean laughed.

“Anyway, you’re not Pentecostal.”

“So what? You can always change. I told her I would be willing to do anything to marry her. She said, ‘I don’t want you to change just for me; I want you to change for God…’”

No sooner had he said that than Jenny walked through the door. Though it was still quite warm outside, she was wearing a straight beige skirt that stretched to her ankles and an off-white blouse that was buttoned around her wrists. Her skin was unpainted around her eyes. Her brown hair hung straight to her waist. She looked like a piece of smooth, unvarnished wood. She was beautiful. Unadorned.

“Isn’t she the greatest wife in the world?” Sean asked, sitting up and slapping his thighs.

“Isn’t he just silly?” she countered, pushing him down with insouciant aplomb.

Earlier in the evening the two of them had invited me for dinner—stewed chicken and rice, Wonder bread and butter. It was the first time I had seen silverware in Sean’s trailer. It was the first time they had received houseguests. All night the two of them alternately bickered and cuddled like the strangers and newlyweds they still were. “You are the most hyper person I know,” she said to him when he jumped on her back and kissed her neck. “You are the most stubborn girl I’ve ever met,” he retorted when she slapped his hand away from the stove. They would snap at each other, apologize quickly, then roll around on the floor in a frantic embrace. “It’s just that time of the month,” Sean whispered. “All girls are like that.” “It’s just right after his act,” she countered. “All circus boys are like that.” After dinner she washed the dishes and took the leftovers to Michelle and Angel while Sean lay on the bed and recounted their story. The number of pillows had blossomed again. Not only mauve, now, but fuchsia and lavender. Sean’s old black blanket had disappeared. So had his gold necklace with the Florida Gator.

“Did you tell him what happened at church?” she said, finally arriving on the bed.

“I was just getting to that part,” he said, putting his arms around her waist.

“Stop it,” she said. “We have company.”

“He’s not company,” Sean said. “He’s Bruce.”

He tickled her for several seconds until she finally gave him a kiss. Then he returned to his story. The day after Jenny moved into his trailer Sean agreed to attend Sunday-morning services at a local Pentecostal church. “It’s not like it came as a total surprise,” Sean said. “In recent weeks I had been reading the Bible a little with Michelle and Angel. In Commack a priest came to the lot several times and showed us the right way to read it. Once you know, it all makes sense. For Jenny’s sake I agreed to go.”