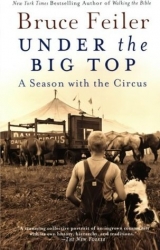

Текст книги "Under the Big Top: A Season with the Circus"

Автор книги: Bruce Feiler

Жанры:

Прочие приключения

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Second Half

9

The Star of the Show

Elvis came back to life in Queens. Big Man met him at the gates. For the two loudest crooners on the show—actually whiners is more like it—the great showdown finally occurred in New York when they battled each other grunt for grunt in the only ring that isn’t round. It was the brawl of the year on the blacktop lot around Shea: “Blue Suede Shoes” meets “Jailhouse Rock.”

In fairness, Sean and Big Man weren’t the only ones whose blood was boiling in New York. By late July we had reached that time of the season commonly referred to as “that time of the season.” Johnny was mad at Jimmy for paying Sean to usher (most performers were required to do it free). Jimmy was mad at Sean for implying his contract didn’t demand it. And Sean was mad at Elvin, who ultimately concluded that Sean should stop complaining and give back the money. The Rodríguezes, meanwhile, were mad at the Estradas for not letting the Quiroses borrow their tumbling mat, while the Estradas were mad at the Quiroses for not cleaning the mat when they borrowed it the first time. Everyone, of course, was mad at the clowns—for spilling water in the ring, for splashing water on the swing, and for getting so much applause without ever having to usher. “It’s called the midseason blues,” said Henry, the cryptic sage of Clown Alley. “You feel like you’re taking these long strokes and you don’t know if you’re closer to the beginning or the end. Then suddenly you realize you’re about to drown.”

Drenched in self-pity, the show arrived in New York at the same time as the most devastating heat wave in a decade. For most of our first week—in Forest Park and the Bronx—the seats were mostly empty as the performers struggled through a liquid assault much more deadly than mud: humidity. The temperature in the rings was well over 100 degrees: near the top of the tent it was closer to 115. Mari Quiros nearly fainted while doing a split on the high wire. Her husband, Little Pablo, nearly slipped from the trapeze when the chalk on his hands turned to milk.

The clowns, once again, probably had it the worst. With the number of shows now at seventeen a week, we were required to be in makeup nearly twelve hours a day, an exercise that is best likened to soaking in a tub of congealed perspiration consommé. Grease may be repellent to water, but greasepaint is not repellent to sweat. In fact, by the time I put on my stocking, skullcap, T-shirt, dress shirt, gym shorts, trousers, socks, shoes, bow tie, jacket, gloves, and hat, just the mere act of opening my eyes brought torrents of chalky white perspiration gushing from my powdered pores. That, of course, is when the white stays on. You can always tell a clown in heat by the rash of pink flesh peeking out of his white upper lip or the beads of red moisture dripping off his vanishing nose. Naturally the worst thing for a clown is to reveal to the world his true colors.

Besides the heat, we still had to grapple with the trials of producing a circus in the middle of the Big Apple. Arriving in New York dramatically increased the level of tension on the lot. One clown started sitting out every gag to watch over the Alley, while Sheri from concessions bought a two-way walkie-talkie system to communicate with her children, whom she kept locked in her trailer during the show. Dawnita even placed a sign next to her door that said: DANGER: BEWARE OF LIVE COBRAS. While some of this anxiety may have been misguided, much of it was well founded. Driving into Manhattan via the George Washington Bridge, crossing the Bronx on a two-lane, two-story pockmarked thoroughfare, passing into Queens over the thoroughly clogged and completely unmarked Throgs Neck Bridge, and driving down Flatbush Avenue through Little Havana, Little Haiti, and Little Sicily might be expected to produce a certain amount of stress even under ideal conditions. But imagine doing this in the middle of the night, on an empty stomach, with a child in your lap and a map on your dash, after walking on a high wire all day or playing the trombone for ten straight hours, all while driving a thirty-five-foot mobile home with a teeterboard in the kitchen, a tractor-trailer full of hungry elephants, or the world’s largest cannon. Even my twenty-three-foot Winnebago, which took most of the bumps in stride, responded to the relentless abuse by spewing out my paper towels in a knee-high serpentine mulch and tossing my microwave onto the floor. Anyone who dreams of running away to join a circus should take a test-drive first.

When we arrived at Shea Stadium at the end of our second week in New York, the collective tension was beginning to show. On Friday, Marcos and Danny were walking home from a movie and just missed being hit by two bullets fired at random from a passing car. On Saturday, Kris Kristo had a near-crisis with a woman he picked up in a bar. “We went back to her place and screwed, went for a walk, came back, and went to screw again. Only that time I couldn’t get it up. But the great thing is, around here when you get cable you automatically get the porno channel. So when I was lying on top of her and couldn’t get hard, I picked up the remote control, switched to the porno channel, jerked off, blew my load, and switched the channel back—all without her knowing it.”

By Sunday afternoon the silliness and sordidness brought on by the City finally came to blows. It happened in front of Clown Alley.

Sean stepped out of the tent just before intermission of the 4:30 show. His cannon suit was unzipped to his waist and pulled down off his shoulders. His hair was freshly combed with the new winged bangs he had recently adopted. “I never used hair spray before in my life,” Sean had remarked. “Now I can’t get enough of the stuff.” His hair spray was indeed glistening in the sun, which itself was careening off the lights in Shea Stadium, where the last-place Mets were due back for a home stand the following day.

“It started during the first show,” Sean said. “I sat down next to Big Man on one of those sets of three red chairs. There was a magazine on the seat, so I put it in the chair between us. He looked at me and said, ‘What the hell did you do that for?’ I said, ‘Is that yours?’ He said no, but looked at me real funny. He has had that attitude ever since he stole those tapes in Willingboro and I told him to watch what he did.”

Sean left the tent without incident. An hour later he returned.

“During the second show I sat down beside him again. Once again he looked at me real aggressive, and when I went to help lead out the horses he put his hand to his crotch and pretended to masturbate. That pissed me off. He said if that was how I felt I should just come and fight him right there. I wasn’t in the mood, so I got up and left. The next thing I know he followed me outside.”

As soon as Sean stepped out of the tent Big Man stalked out after him. Sean turned around and stopped in place, and for a moment the two men just stared at each other like dogs staking out territory. Shimmering waves of heat floated up from the pavement. The sun beat down on Sean’s exposed back and Big Man’s broad neck. A small crowd began to gather. After several tense moments Big Man began to dance, bobbing up and down like a mock prizefighter with his fists in front of his face. Sean kept his arms at his side but began to bob and weave as well. At the time it looked like simple posturing. Big Man was considerably taller and heavier, but Sean was much quicker on his feet. Perhaps sensing this, Big Man feinted several times in Sean’s direction before dropping his arms and turning away. For a moment the episode appeared to be over, until Sean—unexpectedly, inexplicably—pumped his arms, lifted his fist, and swung at Big Man’s head.

“Pow! I hit him right over his eye. Dropped that sucker right to the ground. He didn’t even know what hit him. Then I jumped him and started hitting him, kicking him, beating his ass.”

As soon as Sean jumped on Big Man’s back, several people jumped on his and tried to pull them apart. Charlie, the aging mechanic, was the first to arrive, but Sean pushed him away with ease and continued pounding away. As Big Man tried to crawl toward the tent, Sean clung to his back, eventually riding him underneath the sidewall and behind the seats.

“I lost my head,” Sean said. “When I get scared, I get angry. It’s almost like I lose my mind. Scared…angry. Scared. Angry. When that fear turns to rage there’s no stopping me. So when that son of a bitch stood and started walking toward the tent I attacked him from behind. I started punching him in the back of the head and pushed him through the side flap. Everyone in the seat wagon was watching. Some boys in the top row were cheering me on. I even hit my hand on the pole and cut myself with my bracelet. I might have killed him if I had a few more minutes, but around then Marty came and pulled me away.”

Big Man, for his part, was not so nonchalant. His job was not so secure.

“Everybody’s trying to make out like it was my fault. All those Mexicans, those whites, they were telling the manager that I pushed him. I never laid a hand on him. He had been bothering me since the first show, actually since New Jersey. I finally had enough. I told him to stop. Then he punched me from behind and I fell flat on my ass.” By the time the fight was stopped Big Man was walking with a limp; his upper lip was swollen from a blow. His red Clyde Beatty shirt was stained with blood. “Now what am I supposed to do?” he asked. “They told me if I didn’t call the police I could stay, but if I did they would fire me. They wouldn’t even take me to the hospital to get stitches.”

“So what are you going to do?”

“I called my uncle. He’s coming with all my people tonight. After that I’m going to decide.”

“Why is he bringing so many people with him?”

“Why do you think? They want to see the show.”

I had to smile. Here was a man who had been on the show for less than four months, who had already been fired once for shoplifting, had been to jail, had been rehired, and now had all but been fired again for getting into a fight with the Human Cannonball, and he decided not to leave the one place where he obviously wasn’t wanted until his family could see the circus—not just any circus, his circus.

“And after that…?”

“After that I’ll decide.” His voice was hardly optimistic. “But I don’t really have much choice, now do I? He’s the star of the show.”

That star finally crashed on Staten Island.

As he had predicted, Sean hit the pavement before the end of the year. It happened during the second show on the last Monday in July. For a full twenty-four hours after his inglorious bout Sean was walking with a little more swagger and a lot more attitude. The previous night, as Sean, Danny, Kris, and I were lounging around my camper eating bagel sandwiches and drinking Yoo-Hoos, Sean was still boasting about his exploit. “I just whipped that nigger’s ass,” he said. Hubris never knew a purer breed. The next day his swank got even bigger and Sean felt so invincible that he didn’t bother to sew a small rip that appeared in the air bag after the first show.

“I left the barrel as normal,” he said. “I saw the three dots on the air bag where I usually land, but then as soon as I hit the bag everything went into a spin. From point A—getting shot—to point B—landing—everything is usually slowed in my mind because I do it every day. Anything past that is just a blur.

“This time, as soon as I hit the bag it just ripped. It didn’t even slow me down. I landed on the seam in the middle and immediately ripped open a twelve-foot hole. At that point I was moving so fast I slid, bounced, and rolled around in the canvas. At first I didn’t know where I was. I looked back and saw the tent through the hole and realized: Good Lord, I’m in the bag.”

Outside the bag, when Sean didn’t reappear promptly the whole cast nearly erupted in panic. As background players in the finale we had certain rhythms we were accustomed to as well: he starts at point A, he lands in point B, then he emerges and sprints to point C and takes his style in the center ring. When Sean didn’t move from point B to point C our internal clocks sounded an alarm. Dawnita went dashing toward the bag. Several of the Rodríguezes covered their mouths in horror. Jimmy snapped to attention. “Turn off the lights! Turn off the lights!” Someone even whispered the unthinkable. “Oh my God! I think he’s dead.”

Inside the air bag the darkness only heightened Sean’s confusion.

“I looked around to make sure I didn’t break anything,” he said. “I was in shock. I didn’t know what was going on. I made sure everything was all right—my bones weren’t popping out or anything. I moved my toes to make sure I wasn’t paralyzed. That’s always the first thing that runs through my mind. I heard Jimmy say something about the lights. I heard people calling my name. They knew I was somewhere, but they didn’t know where. They were looking for me in the middle of the bag, but I was at the end with all this material on top of me. Finally I managed to climb outside. Several people grabbed me, but I told them to leave me alone. ‘I’m all right. I’m all right. Let go. I’m all right.’”

Sean staggered to the middle of the center ring. The performers scampered back to their places. The lights came up in a blaze of victory and Sean Thomas accepted the accolades of the audience, most of whom were undoubtedly convinced they had just witnessed a perfect display. Then chaos descended.

Standing outside the tent after the show, most people barely waited for Sean to explain what happened before hurrying off to their air-conditioned trailers. The truth was, many performers were still upset with him for losing his control the previous day. “Don’t get me wrong,” Big Pablo had said. “I’m a performer, so I back Sean. But in Mexico if somebody sucker-punched somebody else like that, even his friends would beat him up.” The workers, meanwhile, took a parallel stand. “Look, I’m a worker, so I back Big Man,” said Darryl from props. “But to tell you the truth, he had it coming.” Class warfare is alive and well…so is stabbing your friends in the back.

By the time I removed my makeup and stopped by Sean’s door he was already all alone, and already in excruciating pain. “My leg’s all swollen up,” he said, “and I can’t even move my ankle. Plus one side of my ass is already twice as big as the other.”

“I think you should go to the hospital.”

“Royce said he’d take me but he couldn’t stay.”

“What about everyone else?”

“They say they can’t be bothered.”

“Would yòu like me to go with you?”

Sean looked genuinely relieved. “And sit with me all night…? That would be great, bro’.”

It was just after ten o’clock on Monday night when I drove the world’s largest cannon into the parking lot of Staten Island University Hospital, a boxy beige institutional building tucked away behind a mental facility and a shelter for unwed pregnant women on Father Cappodano Boulevard. We had come a long way from picture-preppy Winchester, Virginia. Inside, dozens of bedraggled bodies littered the vinyl waiting-room couches, with a wide variety of bandages, ice packs, and open sores on their appendages and a generic, seemingly hospital-issued dazed look on their faces. I stepped up to a waist-high counter and was handed a clipboard with a registration sheet attached. I entered the name “Sean Thomas” in the empty space and briefly described his injury. Then we went to wait.

And wait.

“Sean Thomas. Sean Thomas. Please come to the triage room.” The announcement came over an hour later. By this time Sean needed a wheelchair.

“No problem,” the nurse informed me. “Wait right here.”

And wait some more.

Twenty minutes later, Sean was summoned for a preliminary examination. That was followed fifteen minutes later by a supplemental evaluation. Thirty minutes after that we were beckoned again.

“Good evening, my name is Elizabeth and I’m going to ask you a few questions.” Elizabeth was wearing a bright green dress. “First of all, would you like to pay with cash, check, credit card, or bill?” Our initial registration, our subsequent evaluation, even our supplemental examination were just warm-ups to our most important test: the financial investigation. After Sean asked her to send him a bill, Elizabeth proceeded down the list of queries. Who is your employer? The circus. What is your job? The Human Cannonball. Where do you live? The world’s largest big top. With each response Elizabeth grew increasingly concerned.

“Where should we send the bill if you can’t pay?” she asked.

Sean thought for a second, then said, “My parents.”

“And their names?” she asked.

“Tim and Joyce.”

“Thomas?”

“No, Clougherty.”

“Clougherty?”

“That’s right, Clougherty.”

“But I thought your name is Thomas.”

“It is.”

“Then why are your parents named Clougherty.”

“Because that’s my name, too.”

“Your middle name?”

“No, my last name.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Look, I’m in the circus. Sean Thomas is my stage name. Clougherty is too hard to pronounce for television shows and all. Did you see me on TV last week?”

“No.”

“I’ve been on four shows, you know: Street Stories, I Witness Video, Regis & Kathie Lee, Peter Jennings—”

“Excuse me.” A lady stuck her head around the corner. “My grandmother is very sick out here. Would you stop wasting time.”

“Sorry, lady,” Sean shot back. “First come, first served.” Turning back to Elizabeth, he added, “Anyway, Clougherty has ten letters, so I don’t use it.”

“This is too much to handle,” Elizabeth said. “I think I’ll just call you Thomas.”

She printed out a four-page form, had Sean Thomas (Clougherty) sign it five times, then motioned us down the hall. It was already nearing midnight.

“Hell, this wheelchair is no good,” Sean complained as I began rolling him toward the X-ray department. “I can’t even do a spin in it, like Elvin’s.” As we rolled past various open doorways asking for directions, we met several women. One was doing CAT scans, another sonograms, two were visiting patients. With each one we met Sean tried out his routine: “Hi, I’m the Human Cannonball. Did you see me on TV?” Each one was underwhelmed. “Hell, I can’t pick up anybody in this wheelchair,” he griped. “I can’t even get any sympathy pussy.”

Finally we met a woman coming out of an elevator who volunteered to give Sean his X rays. She led us to the radiology lab and together we lifted Sean underneath the machine. “Do you think you could radiate Sean’s ego while you’re at it?” I said. “Won’t that make it smaller?”

“Honey, that won’t make it smaller,” she replied. “Only brighter.”

With the X rays taken, I rolled Sean to the doors of the emergency room, where he waited to get his leg evaluated and where I was kicked out and told to wait in the lobby. An hour and a half later Sean emerged again, this time on crutches with a brace on his knee, and we were allowed to leave. As we were going, I asked Elizabeth for a place to eat and she directed me to two diners on the “Boulevard,” just around the corner. One had stairs, she warned, the other did not. Unfortunately, I turned left at the light (the steering was a little loose on the cannon, but the pickup was quite impressive) and ended up with the one that had stairs. COLONNADE RESTAURANT, the lighted sign said. OPEN 24 HOURS.

I parked the cannon behind the restaurant and, rather than climb the one flight of stairs with a crippled cannonball, we headed up the wheelchair ramp in back that led to a glass door marked HANDICAPPED. I pushed on the handle, but it was locked. I knocked. Four waiters looked up from their pads and quickly looked down at their feet. I knocked louder. The cashier looked up from her register and waved me away from the door. This was not encouraging. Neither of us had eaten since lunchtime, and since then Sean had been shot from the cannon, bashed by the bag, bandied around by the hospital, rebuffed by the nurses, and, even worse, totally humiliated to discover that not one person in all of Staten Island had seen him on TV. I knocked a little louder the third time and even waved one of Sean’s crutches in the window to indicate that we were, indeed, handicapped.

No sooner had I lifted the crutch overhead than the owner of the diner, a tall, thin man with a turban around his head, came storming out of the kitchen, running across the floor, and started berating the two of us directly through his still locked door.

“What the hell are you boys doing!?!” he shouted. “Are you trying to break down this door?”

Fed up at this point, I started down the ramp. Sean, however, was hardly so mild-mannered. He was the Human Cannonball. The Daredevil of the Decade. The Great DD. He had a reputation to uphold. His response was to take one of his two wooden crutches and begin beating the door, aiming the rubber-cushioned part directly at the owner’s face. Now quite animated himself, the owner reached into his pocket and began fumbling for his keys, while I grabbed Sean by the shoulder and pulled him away.

We hurried down the ramp, hopped into the cannon, and drove around the corner. As soon as I reached the light at the corner, however, I began to reconsider what had happened. Even though we had lost the battle, maybe we could get retaliation, I thought, by filing a complaint against the restaurant with the city of New York. It would be the ultimate revenge of the nerds. I pulled the cannon to a stop, left Sean in the front seat, and walked up the stairs.

“Excuse me,” I said to the lady at the register. “I would like to know the name of the man who refused to open that door.” No sooner had I spoken than the man himself appeared in the foyer and started berating me again. “I’m not going to tell you a damn thing!” he shouted. “In fact, I’m going to call the police.”

I laughed. “You’ve got to be joking,” I said. “We didn’t do anything wrong.”

The man picked up the telephone and dialed 911. “These two punks are trying to break into my restaurant,” he shouted. He told the dispatcher his name, his address, and his telephone number. As he did, I discreetly wrote each of them down.

“Now stay right here,” he raged at me when he was done. “The police are on their way.”

“As I walked back to the cannon to tell Sean, the owner walked directly behind me and came to a stop in front of the barrel. With his fists cocked at his waist and his face swelling like a child’s, he looked like a taller, thinner version of Sean: the Short-Order Cannonball. Faced with such vaudevillian valor, we decided to wait. Five minutes passed. Then ten. After fifteen minutes I stepped out of the cab and said to the man, “Sorry, it looks like the cops aren’t coming. If they do, just tell them they can find us at the circus.”

I started up the cannon and drove to the light. Just at that moment the cops arrived. For a moment I was overcome by the thought of a high-speed chase through New York City at the helm of a thirty-foot-long silver-and-red cannon with a stream of blue-and-white police vehicles stretched for miles behind us as we sped across the Verrazano Bridge, up Wall Street and the FDR Drive, through Central Park, down Fifth Avenue, past F. A. O. Schwarz, Tiffany, and Saks, before dashing to safety on the Staten Island Ferry and floating triumphantly alongside the Statue of Liberty as our pursuers snapped their fingers in frustration: “Damn! Foiled again.” Then I changed my mind and pulled to the curb.

By the time I got out of the driver’s seat the manager had already headed off the officer and was ranting about how we were in jeopardy of putting him out of business, how we wanted to break down his door, how we were a threat to Western civilization, or at least that much of it that is practiced on Staten Island. This little tantrum only riled Sean even further. By that time he had burst from the cannon and was waving his crutch in a manner that seemed to validate everything the owner was saying. I motioned him back to the cannon.

“Good evening,” I said to the officer when the owner was done. I stuck out my hand in greeting. He looked at me skeptically. I started explaining what had transpired, having already decided that I was going to bore this poor officer to death with every detail of our evening. “We’re with the circus,” I said. “We’ve come to Staten Island to entertain the people…” What followed was the kind of sickly-sweet speech that came partly from my experiences as a onetime student in peace studies and partly from my experiences as a teacher’s pet. “My friend was seriously injured during our show tonight…The kind people at the hospital recommended that we get something to eat at this diner.” The more obsequious I became, the more bemused the officer got and the more irate the owner. He interrupted me several times, jabbing his finger into my chest and saying things like “Do you know how much that door cost?” and “If I keep that door unlocked people will leave without paying their checks.” Each time he burst into a tirade I would turn to him and say in my most angelic voice, “Excuse me, sir. I didn’t interrupt you while you were speaking. Now, if you don’t mind…”

By the time I finished the officer was almost asleep. He turned to the owner of the restaurant and asked, “So, is there any damage?” The manager seemed stumped. He thought for a second, then said, “No,” at which point the officer turned around, got into his car, and drove away. I nodded and walked back to the cannon.

The next day I telephoned the New York City Department of Health.

“I would like to file a complaint against a restaurant for violating my handicapped rights,” I said to the woman who answered my twice-transferred call.

“Were you in a wheelchair?” the woman asked.

“No, I was on crutches.”

“Then you weren’t handicapped.”

“What do you mean I wasn’t handicapped? I had just come from the emergency room, where I had been in a wheelchair.”

“Were you in a wheelchair at the restaurant?”

“No, but I couldn’t walk up the stairs.”

“Handicapped means you have to be in a wheelchair.”

“Okay,” I said. “Then I would like to file a complaint against a restaurant for violating my civil rights.”

“You don’t have any civil rights to be in a restaurant.”

“Sure I do. They were keeping me out just because I couldn’t walk. They have to keep their doors open to the public.”

“No, they don’t.”

“Yes, they do.”

“No, they don’t. People might leave without paying the check.”

“Okay,” I repeated. “If that’s the case, I would like to file a complaint against a restaurant for violating my legal rights.”

“Fine,” she said. “Call a lawyer!” And with that she hung up the phone.