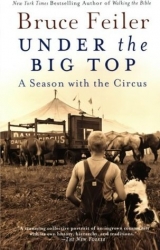

Текст книги "Under the Big Top: A Season with the Circus"

Автор книги: Bruce Feiler

Жанры:

Прочие приключения

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

As soon as he got outside he saw the blood. Then in front of the cage he saw the woman. She had walked from inside the tent in the middle of the show. Arriving in front of the Lilovs’ truck, she decided to feed a hot dog to one of the bears. They look so cute, she must have thought. Surely they must be hungry. Undeterred by the multitude of DO NOT ENTER signs, the woman climbed over the portable orange fence, stepped up to the truck that held the bears, and stuck her hot dog through the narrow gap at the bottom of the cage.

“She picked our worst bear,” Inna recalled. “That one doesn’t like anyone but me. She hugs me. She kisses me. But she doesn’t even like my husband. The lady went right for her cage.”

Predictably, once the bear caught sight of the hot dog she immediately lunged for the treat. When she did, her paw got stuck in the woman’s bracelet and her claws dug deep into the woman’s hand. The woman started to scream. Venko sprinted from his trailer. He grabbed a shovel from the side of the truck and swung at the bear. As he did, the bear let go of the woman, but not before tearing a hole in the top of her hand and ripping her index finger to shreds. Blood was spewing everywhere. The woman fell back in horror. For a moment there was silence, then suddenly, inexplicably, she got up to leave.

“She was drunk,” Venko said. “She was trespassing. She was attacking my bears. I told her to fucking stay where she was.”

Inna came running out with a camera. The police showed up and made a report. Eventually an ambulance arrived and drove the woman to a hospital. For the time being everyone was in shock. The encounter was the worst nightmare of everyone on the show. It seemed to highlight all of the hazards of life in the circus: the danger of working with animals, the perils of dealing with the public, the threat of disaster at any moment—even outside the ring. Like anxious parents who fret for their children as soon as they step out of sight, performers live in constant fear that their families will be taken hostage by events such as this. But what developed next in this episode surmounted everyone’s past experience. In fact, it seemed to transcend the rich history of the circus and embed itself firmly in the culture of the present. The one fact that haunted all of us for months, the one detail that made this incident with the bear representative not just of the circus but of American society in the 1990s, was that the boyfriend of the woman who fed her hot dog to the bear announced to doctors at the hospital that the woman was HIV-positive. As a result, in the harried days that followed this already horrid episode, the show had to get not only the three members of the Lilov family but also their five Siberian bears tested for the AIDS virus.

When I heard this news, all I could think of was Venko’s beleaguered admonition: “People are fucking stupid, my friend. You just don’t understand.”

As soon as Dobush completes his handstand on the rings the act accelerates through a series of increasingly complex tricks: Tampa rolls backward on the parallel bars; Peggy walks on a spinning barrel; Dobush catches a series of juggling rings and slips them necklacelike over his head. For the final trick the prop crew brings out a giant trampoline and sets it in the center of the ring. Venko leads Dobush onto the bright red trampoline. With the drummer accenting the bear’s every bounce with his lower toms and sixteen-inch cymbal, Dobush springs several feet in the air like a giant furry version of one of those juvenile bat-a-balls. The audience applauds enthusiastically, but Venko barely smiles. In truth, his heart is no longer in the ring.

After the disaster on Cape Cod, Venko slowly descended into a low-grade rage about the circus. The HIV tests on the bear, performed by a special veterinarian, proved negative. The tests on his family were negative as well. But still Venko had had enough. “I’m preparing myself to leave show business,” he said. “I don’t need this anymore.”

“Are you sad?” I asked.

“Bruce, you’ve been here too long,” he said. “You are starting to think like these people. Just because I live in the circus doesn’t mean I have to die here as well. Do I want to be seventy years old and driving two hundred miles to the next lot and arriving at five in the morning? I want to have a normal life. I want to have a house. I want to work five days and have two days off. I want to go fishing. Now I must work twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, three hundred sixty-five days a year. When I go to a Chinese restaurant I must be thinking what would happen if the cages came open. When I go to the supermarket I must think what happens if my fence breaks. Sometimes I do not sleep at night. The reason is if something happens to my bears I am lost. And if something happens with the public they sue me.”

The lady who fed the hot dog to the bear did eventually sue the circus. Even though she was trespassing, the show settled out of court for $9,000.

“This is a great country. You can work very hard and make a good living. When I first came to this country in 1973 I was making four dollars a week. Ten years later I was making only $105 dollars a week from Kenneth Feld. Now I make a good living but I have $1,000 a week in fixed expenses. That is okay when I get paid, but when I have three weeks off in the winter that starts to cost a lot of money. Every year I have to begin the season with no money. This is no life for a family. I’m just happy I’m not like the rest of these people. I have something else I can do.”

When he did leave, Venko said, he planned to give his bears away to zoos and open a twenty-four-hour trailer repair business in Florida. Still he vowed not to forget where he came from, or what caused him to leave. “I’m going to call my company Royal Bear Trailers,” he said, “and I’m going to ask every customer that comes in if they are animal rights activists. If they say yes, I’m going to charge them triple.”

6

Death of a Naïf

Soon after Ahmed’s wife, Susie, had her baby, something happened to the show. We were in New Jersey by then. June was on its way. Suddenly the show was losing its freshness. Overnight a sort of seven-week itch consumed the cast and crew.

In Clown Alley, meanwhile, discord still reigned, though I was growing more settled. In the two months I had been clowning I had slowly warmed to the ring. At the start of the year I had often stared at the ground during shows. It wasn’t nerves, just concentration. With every lot a different surface—asphalt, mud, grass, or gravel—every day presented a different danger. Sometimes I would slip on an anthill during the firehouse gag and land on my back. Sometimes I would trip on a rock and land on my face. This was hilarious for the audience but painful for me. Finally Elmo pointed out during one of his visits that I should stop playing to my feet and play to the audience instead. “Don’t make eye contact with anyone,” he said, “but make faces in their direction. If you don’t look at anyone in particular, everyone will think you’re looking at them.”

As a performer, my relationship with the audience was not what I would have expected. In many ways the performers don’t do the show for the audience. The size of the crowds varies widely, from frequent packed houses of over 3,000 to the occasional dismal showing of under 200 (Rock Hill, at 157, was the lowest of the year), and performers can’t rely on them for motivation. As a result, they must rely on something higher—like a love for the circus—or something lower—like the promise of a paycheck. Moreover, the size of the crowd is often less important than its enthusiasm. In Phillipsburg, New Jersey, near the Pennsylvania Dutch country, the show sold out but the people were taciturn. In Willingboro, closer to Philadelphia, we had only half houses but they were mostly Latin and cheered with zeal. When the Flying Rodríguez Family was introduced as the “Pride of Mexico,” the crowd whooped and whistled with patriotic hysteria. Unfortunately they were less adoring of the Rodrinovich Flyers, not realizing they were Mexican as well.

For me, each particular audience was less important than my overall attempt to develop my clown persona. I learned early how to turn on and turn off my clown on demand—“on” when I stepped inside the tent, “off” when I stepped out. Not particularly limber, I had been developing a character that was upright, almost formal: an inept maître d’ with a relentlessly sunny spirit, blind to the restaurant burning down around me. Ironically, even though the historic distinction among clown categories (whiteface, Auguste, and a few minor characters, such as the tramp) has all but disappeared in recent years, I fit naturally into the role of the traditional whiteface: a straight man and perfect target for all the manic Augustes around me. This was particularly true in the firehouse gag.

Like everyone else in the Alley, I joined in the rush to find new bits to add to the gags. During the ladder routine in particular I needed something to do. I considered normal things that firemen do that would be funny when done around a burning house, such as selling tickets to the firemen’s ball; as well as things that normal people do over a fire that would be funny for a fireman to do, such as roasting marshmallows. In the end I settled on a normal thing that people do to a house that would be funny for a fireman to do, namely, painting the outside. This idea was made possible by the fact that Marty had the perfect prop, an oversized painter’s palette with a giant scrub brush on a stick. A few days later Jimmy was lecturing a few of us over dinner about the virtues of sight comedy over slapstick when he asked, “By the way, who came up with the painting?” I signaled that I had. He raised his eyebrows approvingly, but didn’t say anything further. He didn’t have to. I was learning my way.

Unfortunately, no sooner had this prop come to symbolize all the virtues of the Alley than it came to represent its faults. While the clowns pretty much cooperated during the gags, once out of the ring the boys would usually just return to the Alley, take off their wigs and pants, and sit around in their undershorts telling off-color jokes. I had been trying to counter some of the tedium and improve my relations with the Alley by asking a few of the boys—particularly Marty—to give me some pointers on being a clown. Although at nineteen he was the youngest, Marty was also one of the hardest-working and most talented of the clowns. In his loudmouthed persona of the Village Idiot he was also the most outspoken, the most conceited, and the most resentful about my being considered a clown. He would constantly complain about my makeup, the way I pulled the cart, even my driving. After passing me on the road one night in the truck he drove for the electrician, he sought me out on the lot. “Bruuuuce,” he said in his whimpering Village Idiot drawl that he never seemed to put away. “It’s considered courtesy to blink your lights at somebody when they pass you.” After several incidents like this, I decided to treat him with the respect he craved and asked him to teach me about taking falls, making bangs, and building props. He eagerly obliged. Soon the problems got worse.

First, he started giving me little pieces of niggling advice. “This is the finale,” he would say. “I think you ought to look more spiffy.” Next he tried to change my makeup. “Your face is really boring,” he would say. “I think you should change it.” Finally, one Sunday evening in Exton, Pennsylvania, he went over the top. The weather had been gorgeous all weekend, but suddenly during our final show the sky darkened and a light rain started to fall. We had already dismantled the firehouse and only the fire cart remained to be loaded into the prop truck for the jump. The palette and brush that Marty had loaned me remained, as they always did, at the bottom of the cart. As the show ended Marty came into the Alley.

“Bruuuuce,” he said in his ingratiating whine. “Will you do me a faaavor?”

“Sure,” I said, “what is it?”

“Tomorrow, take the palette and brush out of the cart, wash them off, put them in the truck, and never use them again.”

Then he spun around and left.

For a moment I was stunned, then dumbfounded, and in the two-and-a-half-hour drive to New Jersey that followed, I slowly became annoyed. The next day, after putting away his prop and replacing it with one I built myself, I pulled up a chair beside him in the Alley when no one else was around. I understood that my presence in the Alley was somewhat unusual, I told him, but I wondered if he would treat me with respect nonetheless.

Marty was caught off guard by my directness. He said he had learned in the circus that you can’t ask people nicely to do things but must treat them like children. Then he apologized. Later that night he complimented me on my bow tie. The next day he asked for my help with his trunk. As with Sean and Kris several weeks before, the less I acted like some silent cartoon (or even a distant writer, for that matter), the more I was accepted into the circus.

In Willingboro, Sean asked me to go to the mall. He was looking for a new pair of high-top sneakers to replace the ones he wore in his act. The twice-daily impact of the cannon launching pad against his feet had completely wrecked the soles of his shoes. It had also all but eliminated his arches and almost ruptured his knees, thereby aggravating what he referred to as his rickets, the euphemism for his bowleggedness. When he was on CBS’s Street Stories, Sean had mentioned the problems he was having finding shoes with sufficient support and afterward had waited expectantly for several weeks for an endorsement contract from Nike. Unfortunately, it never came. Michael Jordan got millions for jumping fifteen feet from the foul line and dunking a ball in a net; the Human Cannonball can’t even get a free pair of shoes for getting shot one hùndred and fifty feet twice a day from a cannon and dunking himself in a net. Clearly the scales of justice don’t weigh all acts the same.

In the mall our subject wasn’t feet, but guts. By late May we had entered a several-week stretch of towns where we played only mall parking lots—York and Exton in Pennsylvania; Voorhees and Princeton in New Jersey; Fishkill and Middletown in New York; Danbury in Connecticut. The circus likes playing malls because they are central, easy to find, and mothers feel safer bringing their darlings to a circus in front of TGI Fridays than across the street from Al’s Hubcap and Fender at the fairgrounds three miles out of town. The malls like having the circus because it brings in customers, generates publicity, and enhances their reputation as the new town centers of suburban America. The performers like being at malls because the men can find bars to watch sporting events at night, the women (and men) can go shopping during the day, and the kids can escape their mothers’ trailer cooking and enjoy a Chick-Fil-A for lunch.

Sean liked malls because of the mirrors. Considering his penchant for fistfighting and mudslinging, Sean was remarkably vain—particularly about his hair. His blond locks were short in the front with Little League-type bangs and long in the back with rockabilly-like ducktails. In every place he spent more than a passing moment he liked to keep a brush—in his trailer, in my trailer, in the front seat of the cannon. Before his act he would usually brush his hair for ten or fifteen minutes in a combination of Herculean narcissism and Samson-like fortification. In Lynchburg, during one particularly marathon grooming session, I noticed with some alarm that four of the metal bristles of his white doggy-style brush were missing. “I bit them off,” he said from the top of the cannon. “The rubber was missing off the tips and the metal was hurting my head. When you brush your hair as much as I do you have to be careful.” In a stately gesture he took one final sweep of his bangs and tossed the brush down to the ground. As he did, Arpeggio appeared alongside the cannon and caught the brush in his hat. “Oh, Mr. Thomas,” he squealed. “Thank you so much. I’ll treasure it always.” “There are a few hairs left in it,” Sean kindly pointed out. “You can keep them if you want.”

Going to the mall with Sean, even a run-down one like Willingboro Plaza, was to be a bit player in this ongoing parody of self-aggrandizement. On the way to Pic-n-Pay we passed a mirror. “Sometimes I look at myself in the mirror and wonder why God was so good to me,” he said. “And the other times?” I asked. “I know why.” To get around this seemingly impenetrable wall of self-confidence, I asked Sean during our walk through the mall to tell me how he met Elvin. He responded with surprising modesty.

Sean’s first brush with the cannon came in 1989, two years after Elvin’s accident, when Elvin first asked his unsuspecting pool boy if he would be interested in joining the circus. Sean said yes; his girlfriend, however, said no. The idea was quickly dropped. Two years later, with no replacement in hand, Elvin again approached Sean. Once again he said yes; more importantly his girlfriend was no longer around. Within a week he was practicing.

“I remember the first time I got inside the cannon,” Sean said, his voice unusually respectful. His posture was much less sure. “The net was up against the lip of the barrel. That was before we had the air bag. I was wearing sweats and Reebok hiking boots. I slid into the capsule and got situated—my legs on the platform, my butt on the seat, my arms crouched at my side. My whole body tensed up. I took the hit—the initial bang when the capsule slides up the track—and I almost passed out. By the time I knew what was happening I was already coming out of the barrel. My heart was beating. I was scared. I ducked my head like Elvin told me to do and the next thing I knew I had landed in the net. You’re supposed to land on your back. Only that time it didn’t work that way. I dragged my feet when I was leaving the cannon and my left foot caught the bottom of the barrel and my shoe was ripped off. I was lucky my foot wasn’t taken off as well.”

“Were you hurt?”

“No. I got up and Elvin said, ‘Are you all right?’ and I said, ‘Yeah, I got my foot caught on the mouth of the cannon.’ ‘You’ve got to keep your legs together,’ he said. So I got in again. That time I was concentrating so hard on keeping my legs together that I spread my arms apart too soon. When I opened up I caught the last two fingers of my left hand on the edge of the barrel and split the webbing between my fingers. My wrist got hurt as well. Elvin gave me the rest of the day off. That’s when I got really frightened. On my way home an old lady pulled out into the road in front of me and I had to swerve my Jeep to avoid getting killed. By the time I arrived at my friend’s house I was shaking like a leaf. ‘Sean, where have you been?’ he said. ‘You’re covered in gunpowder.’ I looked down at my body. My black sweats and red T-shirt were coated in white with splotches of blood everywhere. It looked like I’d been shot. But it wasn’t the shot that freaked me out. It was the lady. She had almost killed me. That’s when I realized my life was about to change.”

For the next several months Sean drove out to Elvin’s house every afternoon at 4:30, took a couple of shots, and slowly learned his way around the cannon. Elvin guided him through the mechanical operations part by part, piece by piece. “It’s kind of Neanderthal,” Sean said, “but it’s brilliant.” Elvin also guided him through the mechanics of flight: keep your back stiff, your legs straight, your toes pointed. Shoot straight ahead, look where you’re going, reach for an imaginary track. Gradually they lifted the cannon higher, Sean flew further. Now his head was straight, his back was firm, but his legs were still lagging behind. “For most people who aren’t gymnasts it’s hard to control your legs,” he recalled. “When you watch somebody dive off a diving board, they can usually control their upper body—their arms and their head—but their legs are always sagging. They have them apart or their toes aren’t pointed. In the air you have to stay perfectly straight, then at the last second, in order to get over, you have to squeeze your butt and point your toes so you rotate over onto your back.”

Within several months opening day arrived. Sean’s parents came to DeLand for the show. His ex-girlfriend was there as well. Sean marched in the opening parade, then almost immediately came out for his act, which at the time followed the tigers. Elvin was frantic with nerves: Sean had never done a shot in the tent, only in the open air. Everyone else was nervous as well. Sean, however, was a beacon of calm. “Elvin said to me, ‘Are you sure you’re not going to freak out? Are you sure you’re not stiff?’ I said, ‘What’s there to be afraid of? Let’s just do the shot.’ So I did the shot. It was perfect, beautiful. Elvin was so excited. ‘I told you I could do it,’ I said to him. He just started to cry…”

Sean went silent for a moment. We had stopped for lunch at a Chinese takeout—chicken with peanuts, Oriental vegetables. He put down his fork. “I can’t say Elvin’s like a father to me because my dad’s an incredible father. Elvin’s different. My dad’s like my best friend, a real-guy kind of father. Elvin’s more like a Leave It to Beaver type of father. My dad was never really strict with me. Elvin’s very bossy. When we left DeLand last year and drove to Brunswick, Elvin asked me to call every day, but I never did. He gets mad, but I tell him I have it under control. He says, ‘That’s why I worry about you. You only call when there’s a problem, so when the phone rings and it’s you, I know that there’s a problem.’”

For Sean’s first several months on the show Elvin’s phone never rang. There were problems, but nothing Elvin could solve. For Sean, cocky about his body as well as his virility, the primary problem was dealing with his colleagues. “I wasn’t from the circus,” he said. “My family wasn’t from show business. They all knew that. I had to be accepted. That was hard, especially on this show where everybody has grown up together. They all said he’s not a performer or anything and now he’s automatically the star of the show. He’s always on TV, he’s got girls in his trailer every night, and he’s got a full page in the program, which, ooh-ooh, is a big deal to these people. To me I couldn’t give two shits, but to them…”

Everyone thought Sean was a snob because he did the cannon. To make matters worse, they thought he was English. “They just wouldn’t speak. I would say, ‘Hi,’ and they would just be cold. It’s that snobbery thing. You know how it is.”

“So how did it change?”

“I kicked a few butts. There were a few rumors around, and finally one day I got mad. If I’ve done something and you’ve seen me do it, tell the whole world, I don’t care. But if you don’t see me do something and you make it up, then I’m gonna get some revenge.”

The first rumor involved drugs. At the beginning of the year Sean made the bang that accompanied the cannon shot by pumping acetylene gas into a balloon. He would turn on a torch, snuff out the flame, then inflate the balloon with the gas. One day he snuffed out the flame incorrectly, and when he went to squeeze the gas the balloon exploded in his hands, shredding his shirt and burning half the skin on his stomach. Nellie Ivanov gave him some baking soda to put on the wound. That night he was sitting in his trailer when some of the workers came by. “They saw me with this pile of baking soda on my table and said, ‘Man, sell me some of that.’” The following day Kris came up to him and said, “Sean, you better watch what you do. Word travels fast around here.” “What are you talking about?” Sean said. “I heard you were selling cocaine to the workers.”

A week later the rumors had him in jail. In Utica, New York, Sean went to watch a Chicago Bulls game on television with Jerry, the clown. In front of the lot they asked a policeman for directions and he offered to drive them himself. “The next morning I got the manager knocking on my door,” he recalled. “Boom, boom, boom! ‘Sean, Sean, are you in there?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ ‘Really?!’ he said. ‘How did you get out of prison?’ As soon as I got out of my trailer everybody was going ‘Hey, jailbird. We heard you got arrested. Big cannon man had a little too much to drink.’” One of the young workers on the front door told everyone Sean had been arrested. “I wouldn’t have been mad,” Sean said. “But word goes back to Elvin. You get one of these shit-ass workers who goes to another show. Say these people want me to work there. ‘Oh, man,’ they say. ‘That guy’s a troublemaker. He’s a bum.’”

To prove he was not a bum Sean decided to beat the guy up. Unfortunately for Sean he never got the pleasure. The man, sensing danger, blew the show first. Sean responded by beating up the man’s friend who had earlier confessed to spreading the rumor. In the prison mentality of the circus, Sean was now considered a man.

“Suddenly people started talking to me. ‘So, how did you get into the business?’ they asked. ‘Tell us, how did you get hold of Elvin? Are you family with the Bales?’ First I couldn’t get a ‘Hi’ from them and now they’re asking me questions. It’s just like they’re doing with you now. ‘So, why did you join the circus? What do you think of life around here?’ As soon as that starts happening you know you’re one of them.”

By the time Sean had finished his story we had finished our lunch and decided to check out the one remaining possibility for shoes, Boscov’s department store. As we cut through Women’s Clothing on our way to Sporting Goods we overheard two women who worked at the store, which was located directly next to the lot. “They must be really weird…,” one of the women said. “You better believe it,” her friend added. “Just wait until they come in here and start washing their babies in the sink.” As soon as we heard this, Sean stopped in place and walked back in their direction.

“Are you two talking about the circus?” he asked.

“Yes,” they said.

“Well, ladies,” he said, yanking up his sleeves, “have you looked out the window? You see those trailers out there? In the circus we live in those, and, for your information, they all have bathrooms. So we don’t need to wash our babies in your sink.” He hesitated for a moment. His skin was becoming flush. Should he stop, he considered, or should he continue? But by now he realized these women weren’t talking about them anymore. They were talking about him. “You see this watch?” he said, now getting caught up in the hyperbole of the moment. “It costs three thousand dollars. This bracelet costs five hundred. That’s more than you make in a week. In the circus we all live in three-hundred-thousand-dollar homes on the beach. We work nine months of the year. In fact, we make more in a week than you make in a month. We don’t need to wash our babies in your sink, and we don’t need to buy anything in your store. And if I were you, I would just shut up.”

He spun in his tracks and stormed out the door. I followed him outside. Later that day a man from the big top department walked into the store through the exact same door and shoplifted two cassette tapes.

Danny Rodríguez knew why someone would steal. Sitting up late the following night in a plastic beach chair near his half brother’s trailer, he was complaining about a lack of money. Hardly starving, he was wearing blue-jean shorts that reached to his knees, black high-tops that climbed to his ankles, and a red Chicago Bulls tank top that hung halfway to his thighs. Basically he looked like a rapper, albeit an immobile one, for underneath his oversized duds he was still wearing a neck-and-shoulder brace from his tumble off the swing.

“Do you know what time it is?” he asked.

“No,” I said.

“No?” he mocked. “You’re not supposed to say, ‘No.’ Don’t you know anything about the circus by now? You’re supposed to say, ‘What do I fucking look like, Big Ben?’ or ‘What am I, a fucking watch or something?’ That’s the way to be a member of the Clyde Beatty family.”

Actually Danny Rodríguez wasn’t feeling particularly close to the family these days. Since the accident it had turned on him full force, starting when his immediate family had rejected his explanation for his fall. Feeling beleaguered, Danny was considering splitting the show. For him it was a matter of money.

“I tell you, this show is rolling in cash. Everyone gets it except us. They have to pay all the marketing people, the cookhouse, and don’t forget the band. Also, it costs over a thousand dollars every time they fill up the trucks with diesel. And all that hay and shit for the elephants. The performers don’t get anything, man. Sean makes less than five hundred dollars a week.”

“A friend of mine came to see the show,” I said, “and I was telling her how much work there is. ‘And of course you make ninety grand a year to do it,’ she said.”

“Shit,” Danny said. “What did you tell her?”

“I told her the clowns make one hundred and eighty dollars a week.”

“Tell her I wish I made that…” As he spoke, a loud crash came from No. 63, where the workers were having a payday bash. Meanwhile one of the bears was wailing in his cage because his brother had been donated to a zoo. “Do you know the only people who make any money on this show? The butchers. One guy made three hundred dollars last Saturday selling hot dogs. You can make six hundred dollars a week selling peanuts. Just look at the trailers. The concession people—Larry, David—they’re the ones with the expensive trailers. Look at what the performers have, driving around in these pieces of shit.”

“But those jobs are hard to get,” I said.

“My cousin is assistant manager of concessions on Ringling. He could get me a job selling Sno-Kones or something. You can make good money butchering, I’m telling you. Somewhere between forty-five thousand and a hundred thousand a year.”