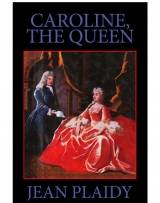

Текст книги "Caroline the Queen"

Автор книги: Виктория Холт

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Lord Fanny

LORD HERVEY lay back languidly as the carriage rattled along the road to Ickworth. He had been long away from home and was pleased to be back; he would not, of course, stay long at Ickworth. A few weeks would suffice with his wife and children; then he and Stephen Fox would go to Court. That was where the excitement lay nowadays.

He gazed across at Stephen—his beautiful beloved companion. All the Fox family were noted for their beauty, but Stephen was surely the most beautiful of them all. Stephen caught his eyes and gave him a look of adoration. Theirs was a relationship on which some might frown. Let them! thought Hervey. What did he care? He was glad to provide gossip, for when a man ceased to be gossiped about, that man might as well be dead. That was his philosophy.

He studied the tips of his elegant shoes with the diamond studded buckles. Everything about Hervey was elegant. The frilly front of his muslin shirt rippled over his brocade waistcoat; his almost—though not quite—knee length velvet coat with the turn back embroidered cuffs, his exquisite lace cravat were all in the latest fashion and his three-cornered hat perched on top of his flowing wig was a masterpiece of millinery. From his person there rose a delicate but none the less pronounced scent and his cheeks were delicately touched with rouge. Stephen said he was as beautiful as he had been in those days ten years ago when he had first appeared to dazzle the Court of the Prince and Princess of Wales who had now become the King and the Queen.

Those days seemed far back in time. Much had happened since. Hervey had fallen in love with beautiful Molly Lepel and married her, for he was proud to be both a lover of men and women. He imagined it gave him a two-edged personality which was interesting.

Molly had suited him. For one thing she had been the most beautiful, most written about, woman of the Court. At least she had shared that honour with Mary Bellenden and there had been a constant controversy in those days as to which of the girls were more beautiful. Molly had beauty and charm. Moreover her personality fitted his. She was a strange woman, his Molly. She had shared his life for those first years without intruding on it. It had appeared to be a perfect marriage—and a fruitful one. Sons and daughters had been born to them and there would doubtless be more for they were both young. He was in his early thirties and Molly was four years younger than he was. She stayed with the children at Ickworth and had no desire to return to Court. She had lived her early life in Courts and had had enough of them. In the country she entertained a great deal, looked after her children, and her life was complete in the world she had made for herself. Hervey visited her now and then as a close friend might; she never questioned the scandals which surrounded him; she never criticized his friends. The fact was that Molly did not care.

Molly was a cold woman without jealousy. Hervey could have his lovers—male and female—and Molly implied it was no concern of hers. When he came to Ickworth he was welcome. It was his home; she bore his name and his children. His preference for others was no slur on her because she had been recognized as one of the most beautiful and attractive women of her day; she could have had lovers by the score; but Molly did not want lovers. She wanted her life to go on as she had arranged that it should; that did not include any emotional disturbance, for Molly had no time in her life for emotion.

A strange ménage, some people thought. But it satisfied Molly and John Hervey. What man, he was asking himself now as the carriage was coming into Ickworth, could have gone off travelling abroad with a beloved friend, and return with that friend to his wife and be received with a cool cordiality which was more comforting in the circumstances than any warmth could have been.

His thoughts were going on ahead of Ickworth, for he had decided that it should be a short stay. And then ... to Court. It would be amusing to renew his acquaintance with the Prince of Wales. He and Frederick had become good friends when he had visited Hanover before the Prince had come to England; in fact Frederick had been quite overwhelmed by the polished manners and elegant charm of Lord Hervey. Later they had resumed that friendship and if Hervey had not had to travel abroad for the sake of his health, it would have progressed still farther.

The thought of his health made Hervey feel a little wan and Stephen immediately noticed this.

‘You are feeling ill?’

‘A little faint.’

‘My dear soul, lie back and close your eyes. I fear the jolting of the coach ...’

The jolting of the coach,’ said Hervey quietly, enjoying his friend’s concern. ‘Nothing more.’

‘Did you take your spa water before we set out?’ ‘I did, I swear.’

‘It should raise the spirits.’

‘My spirits are high enough, dear boy. It is the flesh that is weak. I think I will try that mixture of crabs’ eyes, asses milk, and oyster shells. I have reports that it sweetens the blood.’

‘I will see that you have it.’

‘My dear Stephen! ‘

Such devotion was pleasant; it was for its sake that he had taken Stephen with him on his travels. Dear Stephen! Quite his favourite person at the moment. Stephen had cosseted him, remembered his medicines, listened to his poetry, adored everything he did. He was so much warmer than Molly. Not that he would criticize Molly one little bit. Molly was just the wife for a man such as he was.

‘Close your eyes,’ commanded Stephen. The only time the dear boy commanded was when he was acting the nurse. ‘You should rest for the remainder of the journey.’

Hervey obeyed, and allowed himself to drift into a pleasant state of semi-consciousness when the impressions of Venice and Florence became slightly jumbled together and he was not sure whether he was walking beside the Arno or the Grand Canal. The sun had been so welcome, and he had written a great deal of poetry which he so enjoyed reading to the appreciative Stephen. Sometimes he felt he would ask nothing more but to stay at Ickworth with his family—and Stephen—and spend his days writing.

That would never suit him for long though. He was a mischievous sprite; he must be at the core of life; he must be at Court, stirring up trouble, seeking a high place in the confidence of people through whom he could make himself important—important in politics which played their part in history.

He was too egotistical, too vain, too mischievous to spend his days in retirement.

There would be fun to be had at Court now. Walpole was supreme some said and Pulteney was determined to pull him down. It would be fun to live close to such a battle, to work in the shadows, to use his pen as some men used their swords. Oh, yes, there was a great deal of amusement to be had at Court.

Therefore it would be just a short respite at Ickworth and then away to adventure.

He himself was no politician of fixed ideas. He had been returned as a Member of the House of Commons for Bury St Edmunds some years before and since he had in those days belonged to the Court of the Prince and Princess of Wales and Walpole had at that time been the King’s minister—and that King was George I—he had joined Pulteney’s Opposition.

But George I had died and the Prince of Wales had become George II and although George II had at first rejected Walpole he had afterwards reinstated him. This meant that Walpole was the confidant of the Queen; and as Pulteney was still in opposition against Walpole, there was only one thing Hervey could do and that was change sides. He had become a Walpole man.

He was evidently not a man to be despised. His pen could be vitriolic, his tongue sharp; and Walpole was so pleased to have him on his side that he had asked the Queen to receive him in her household as Chamberlain. This was a source of great pleasure to Hervey; it meant he could be constantly near the Queen, and as he had his duties at Court he could keep in close touch with the Prince of Wales.

Very satisfactory, he was telling himself now. So, after a little respite, to Court he would go.

The carriage was approaching the Ickworth mansion. Hervey opened his eyes. Stephen looked at him anxiously to make sure he was not going to faint and with a little sigh Hervey sat up straight, adjusted his cravat, and smiled at his friend.

‘I feel better,’ he said, ‘but I should like to try the blood sweetener.’

They left the carriage and went into the big hall. Lady Hervey, looking very cool and outstandingly beautiful, was calmly waiting to greet him, her children about her and beside her to Lord Hervey’s astonishment, and some chagrin, William Pulteney.

* * *

Hervey patted the heads of his eldest son, George William, and his eldest daughter whom they had named Lepel. The children had been well trained by their mother and received him as coolly as she did. He was pleased with his family.

‘William guessed that you would be arriving today, and he and Anna Maria are staying here. William is anxious to have talks with you.’

‘Is that so?’ replied Hervey languidly. ‘Stephen will be staying until I return to Court.’

Mary gave Stephen her beautiful smile which meant that she allowed her lips to curl a little and her eyes to open wider.

‘That will indeed be a pleasure,’ she said.

‘Stephen will unpack for me,’ murmured Hervey. ‘I do not trust the servants with some of my precious things.’

‘Of course,’ replied Molly.

As he went to his rooms Hervey was wondering what proposition Pulteney had to put before him. He no longer felt so friendly towards Pulteney as he once had; his friendships did wane quickly. And Pulteney could scarcely feel so kindly towards him now that he had made it clear that he was a Walpole man. Still, it was gratifying that Pulteney should seek to bring him back to the fold. And Molly was evidently eager to help in the change.

Oh, no, thought Hervey. If I am going to Court I must be a Walpole man, for Walpole has managed to become the friend of the King and the Queen.

He turned to smile at Stephen.

‘I do wonder why Pulteney has come here,’ he said. ‘And, oh dear, he has that vixen of his with him! She’s a good looking woman but has nothing to recommend her but her looks. I should like to know the purpose of his visit.’

‘You will soon discover, however he tries to hide it from you.’

Hervey sat down on the bed as though exhausted. ‘You are feeling ill?’

‘A touch of the vertigo; I think I may have to go back to the seed and vegetable diet.’

‘Oh dear, it has such a weakening effect. Perhaps you should rest here at Ickworth for a while.’

‘The diet works wonders,’ replied Hervey. ‘I shall be well in a few days. Put out my pomade and my powder, dear boy. Then you can help me repair the ravages of the journey.’

* * *

Dinner was over and they sat in the drawing room—an intimate family party. There was Molly in flowered silk gathered up at the sides to show her very elaborate blue satin petticoat, the sleeves of her gown billowing at the elbows and ending in frills of soft lace; a patch near her eyes called attention to their beauty; she was now sitting with the utmost grace with which she performed every duty of the hostess. Anna Maria Pulteney was less elaborately dressed. She and Pulteney were very wealthy but Anna Maria did not like spending money and not only was very careful in her own expenditure but saw that her husband was too.

Pulteney was soberly dressed, but Lord Hervey looked like a gorgeous dragon fly in lavender lace and satin; and Stephen, more simply dressed but very handsome, sat back in the shadows ready to show his devotion whenever his dearest friend demanded it.

Pulteney was wondering how far he could trust Hervey. He would have to trust him because he needed him. A man with a pen like Hervey’s should be on one’s side; and the fact that Walpole had been so eager to welcome him into his fold and had secured him the post of Chamberlain to the Queen was an indication of how his services were regarded.

During Hervey’s absence abroad Pulteney had been bringing Lady Hervey to his point of view and as she disliked Sir Robert Walpole intensely she was delighted to help him.

Together, thought Pulteney, we will persuade him.

Conversation was desultory—all knew, except perhaps Stephen, that they were skirting about the subject they wished to discuss. They talked of Venice and Florence. Pulteney was a great talker, one of the most eloquent of men; and he liked to air his knowledge of the classics and throw in a latin tag here and there. Hervey was not surprised that he could not endure coarse Sir Robert. He was highly amused, waiting for Pulteney to come into the attack while he skilfully hedged him off with the beauties of the sunset on the Grand Canal and a discussion of the merits of Michelangelo and Tintoretto.

Pulteney represented Heydon, a borough in Yorkshire, and was one of the leading Whigs. When he had married Anna Maria Gumley, of low birth and high fortune, he became one of the richest men in the country; but Anna Maria had turned out to be a vixen who kept a tight hold on their income and invested it in such a manner that it increased rapidly. At the beginning of his career he had worked with Walpole until Sir Robert had offended him in the year 1721 by not offering him a post in his Ministry. He refused the peerage which was offered him and very soon afterwards became one of Walpole’s deadly enemies. He joined forces with Bolingbroke and that was indeed a formidable alliance, for between them they set up a journal which they called The Craftsmanand with this they began their attack. In it they wrote of a certain Robin (Sir Robert) and the object of the journal was to discredit him and to expose his sly ways to readers. Pulteney was a brilliant writer and Bolingbroke had years before discovered the power of the written word.

Sir William Wyndham, a firm Jacobite, joined with them and the three formed a new party which was made up of discontented Whigs and Jacobites; they called themselves the Patriots and their aim was, they declared, to work for the good of the country and expose the evil clings of those in high places.

And now, thought Hervey, Pulteney is here to attempt to lure me away from Walpole to his Patriots, perhaps to add my literary skill to his in The Craftsman.

Oh, no, certainly not. I have no intention of working under Pulteney and Bolingbroke. I am going to work alone and go my own way; and I shall begin through my friendship with Frederick, the Prince of Wales.

‘William has been a frequent visitor during your absence,’ said Molly at length when there was a pause in the description of European scenic grandeur.

‘How kind of him to relieve the tedium of Ickworth.’ ‘How could there ever be tedium where Molly is?’ asked Pulteney, smiling at his hostess.

Hervey saw the familiar lift of the lips, the opening of the eyes which remained cold and serene.

‘We discussed your talents,’ she said. ‘They are too great to be wasted.’

‘How kind.’

‘If you could persuade Lord Hervey to read his latest poem to you ...’ began Stephen.

But Hervey silenced him with a loving smile.

‘Let us discuss my talents,’ said Hervey. ‘I thrive on flattery.’

‘This is no flattery,’ said Pulteney.

Anna Maria who hated prevarication said bluntly: ‘They want you to join the Patriots.’

Hervey took a kerchief from his sleeve and waved it before his face. Stephen half rose in alarm; Molly sat smiling and Pulteney was very alert.

‘That would be far from simple,’ murmured Hervey. ‘Why so?’ asked Pulteney sharply.

‘I have my appointment to serve the Queen.’

‘Why should you not continue in it?’

‘Do you think Walpole would allow one who was no longer a friend to hold a post so close to the Queen?’

‘That would be for the Queen to decide,’ said Anna Maria.

‘The Queen and Walpole share each other’s views, Madam. What Walpole thinks today the Queen thinks tomorrow.’

There was silence.

‘I should be the loser by one thousand pounds a year,’ declared Hervey languidly.

‘Your father would be delighted to give you a thousand a year,’ suggested Molly.

He smiled at his wife tenderly.

‘My dearest, you think all have as high an opinion of me as you have.’

‘I dislike Walpole,’ said Molly. ‘He is a coarse creature. He tried to seduce me once when I was at Court.’ ‘Unsuccessfully?’ enquired Hervey.

‘Certainly unsuccessfully.’

‘The fool! ‘ said Pulteney. ‘He is a disgrace to the country.’

‘A disgrace who has brought peace,’ suggested Hervey. ‘It was time for peace. There is always a time for peace after wars.’

‘He is credited for the peaceful times and the new prosperity.’

Molly said: ‘If your father would make up the loss of the stipend you receive as the Queen’s Chamberlain would you consider leaving Walpole?’

There was silence in the room.

Hervey looked at them; Pulteney so flatteringly eager; Anna Maria suspicious, the vixen; and Molly, cool, seeming impartial. She wanted him to say yes. She did not care that her husband should be the crony of the man who had tried to seduce her. Fastidious Molly, how she must have hated the coarse old man. Was she capable of feeling elated at the thought of his fury when he knew he had lost such and important adherent as Hervey? It would be interest. ing to see.

‘My father would not do so,’ he said.

‘But if he did ...’

Hervey lifted his shoulders; the assumption was that his loyalty to Walpole hung on his stipend he received as the Queen’s Chamberlain.

* * *

Stephen was alarmed, for he knew more of the secret plans of his dear friend than anyone.

‘If you gave up your post you would hardly be received intimately at the Court.’

‘That’s so, dear Stephen.’

‘But ... it is necessary ... that you are at Court.’

‘Entirely necessary.’

‘And yet ...’

‘Dear boy, you disturb yourself unnecessarily. There is no question of my giving up my post. My father will never agree to pay me the thousand a year.’

‘And if had ...’

‘He never will. My dear boy, do you imagine that I would give up this brilliant chance of being in close Court circles. Never! But if I say to my wife I wish to be on friendly terms with your would-be-seducer, she will be displeased. And if I say to William Pulteney: You are a clever fellow but I prefer to stand in the good graces of one whom I think is more clever—he will be offended. But if I say I do what I do for the sake of one thousand pounds a year, they are only disappointed; they understand and in a way they approve. Madam Vixen also. She has always such respect for money. It’s the line of least resistance. I shall go back to Court, sighing because I must smile at the man who would have seduced my wife, I must call my friend the enemy of one who believes himself to be my true friend. Oh, blessed thousand a year.’

Stephen smiled.

‘How clever you are!’

Hervey nodded. ‘And growing a little tired of the country life. This intrigue here in Ickworth has made me eager to plunge into others. Our stay will be shorter than I had at first planned.’

* * *

Lord Hervey had miscalculated. His father, Lord Bristol, who disliked Walpole intensely, was pleased that his son was considering severing his connection with him.

Molly had written to him explaining that her husband would have allied himself with Pulteney but for the fact that he had to consider the thousand pounds he received each year in payment for his duties as Chamberlain to the Queen. It went without saying that to turn from Walpole would be to lose the post, and it was for this reason only that dear John did not raise his voice against Sir Robert.

The Earl replied to his dearest daughter-in-law that he understood the predicament and was ready to do anything that would help his dear Jack. Therefore he need have no fear of relinquishing his post for his father would make up for all that he lost.

When Molly received the letter she did not run out to the gardens where Hervey was walking in deep conversation with Pulteney; that would have been showing an eagerness and Molly never did that.

She was as serene as ever and it was only after they had dined and were seated together in the retiring chamber when she produced the letter from Lord Bristol.

Hervey listened in dismay. Stephen’s large eyes were fixed fearfully on his friend’s face.

‘So,’ said Pulteney, ‘this matter is settled.’

‘No, that is not so,’ answered Hervey.

‘But you can have no objection now. You will lose nothing. Your father is willing to reimburse you.’

‘I do not recollect saying that my decision depended on this thousand a year.’

‘But you distinctly ...’

‘I do not believe I passed an opinion. You assumed. I said nothing.’

Pulteney was furious. Hervey had never seen him so angry.

‘You said ... you implied ...’

‘I implied nothing. As I remarked, and I pray you forgive the repetition, you assumed. And wrongly as it has turned out. I have no intention of relinquishing my post.’

With that Hervey rose and bowing to his wife and Anna Maria declared his intention to retire. He had a great deal to do for he intended to set out for St James’s without delay.

He left the next day, leaving a furious Pulteney who refused to speak to him.

Molly paid him a placid farewell and went back to her social life, giving parties, looking after the poor of the district, caring for her children, as though she had never attempted to persuade him to leave the Walpole party in favour of the Patriots.

Hervey smiled as the carriage rattled through the Suffolk lanes on its way to London. He was singularly blessed in his marriage. As for Pulteney—a plague on him!

* * *

As soon as Hervey returned to Court he began to ingratiate himself with Frederick. This was not difficult, for Frederick was always looking for new friends, flattery, and excitement; and Hervey, with his wit and elegance, his knowledge of the world and of politics seemed to the Prince a most engaging companion.

Frederick was restive. There were plenty to tell him that he was not treated fairly by his parents. He was kept short of money which was a bore and a humiliation. His sisters with the exception of Caroline openly disliked him; so did his parents. Whenever he could plague them, he would. And there were plenty to help him do it.

But he was not serious by nature. He did not want to be seriously involved in politics; he liked to surround himself with merry companions and drink together, play cards, or perhaps wander incognito through the town to see what adventures came their way.

After the manner of his father, he believed that it was due to his dignity to take a mistress or two, although the company of his own sex delighted him and it seemed to him that Lord Hervey was the ideal companion.

Very soon they were firm friends.

Stephen Fox was a little jealous of Hervey’s devotion to the Prince but Hervey wrote comfortingly to Stephen that the Prince was a fool and that it was not through friendship that they were so much together. While he was forced to spend his time with Frederick his thoughts were with Stephen, and when he was at a banquet at Lord Harrington’s and Stephen’s name was proposed as a toast, he had felt himself blushing as a man’s favourite mistress would have done on the same occasion. Stephen was the person whom he adored more than all the others in the world bundled together. Stephen should remember this—no matter what gossip he heard of Hervey and his new friend.

Like his father, Frederick enjoyed discussing his love affairs. They were numerous he told Hervey. And what of his?

‘Numerous also,’ replied Hervey languidly.

This delighted Frederick, who went on to explain the charms of the daughter of one of the Court musicians.

‘The hautboy player. She is very charming ... and so humble. Yet it cost me all of fifteen hundred pounds to set her up in her own establishment.’

‘Generous of Your Royal Highness. The honour should have sufficed.’

That delighted Frederick. ‘Oh, I like to be generous with those who please me.’

Over-generous, thought Hervey. There’ll be debts.

‘She is very different from Madame Bartholdi. You know Madame Bartholdi?’

‘An excellent singer. I have heard her at the opera.’ ‘A passionate woman.’

‘My dear Fred, most women in England would feel passion for the Prince of Wales.’

How easy it was to please. He liked Hervey to call him Fred. He prided himself on his democratic attitude. That was why he liked to roam the streets at night incognito.

His latest acquisition was the daughter of an apothecary at Kingston and he was constantly taking boat there to see her.

So tiresome! thought Hervey.

He himself had his duties in the Queen’s apartments. Caroline had always liked him; she reminded him of how he used to ride along beside her chaise when the hunt was on and amuse her with his conversation.

‘Are you still as witty as you were then, Lord Hervey?’ she asked.

‘I trust Your Majesty will give me opportunities of assuring you that I am more so.’

She laughed. ‘I hope it is not venomous wit like little Mr Pope’s and so many of his sort. It is so much more clever to be witty and kind, Lord Hervey, than witty and cruel.’

‘Your Majesty being both witty and kind is the cleverest of us all.’

‘There is no need for flattery. You should save that for the Prince of Wales. Ah, how different everything is now. I remember when you were a very young man and were courting Molly Lepel. How is dear Molly?’

‘Very well and very fruitful.’

‘Somehow I did not think you would be father to so many.’

‘I am delighted to be able to surprise Your Majesty.’

‘And I am delighted to see your friendship with the Prince of Wales. If you can teach him to be a little more serious ...’

He smiled. ‘When I am scarcely serious myself?’

‘A little more ...’ She was going to say like yourself, but perhaps that would be too strong. There were always people within earshot and she did not want to start a scandal about herself and Lord Hervey. He was after all about fourteen years younger than she was but she had always had a fondness for him and she knew she brightened when he stood beside her chair and enlivened her with his conversation. George would be furious if there was so much as a breath of scandal about her. And he was difficult enough to handle as it was.

‘A little more princely,’ she said. ‘I fear he wastes his time in the company of ...’

‘Men like myself?’

‘No, you will be good for him. I am sure of it.’ She turned away. She would have to be careful.

Hervey was well aware of her caution and was amused by it. There was nothing he liked so much as to exert his charm, and to have made the Queen aware of it delighted him.

Perhaps he should spend more time near to her.

He noticed one of her maids regarding him with some interest, and when he left the Queen’s presence he found her at his side. She was very handsome and very voluptuous. He knew of her. She was Anne Vane at present mistress of Lord Harrington, although Harrington was by no means the first man to have been her lover.

‘My lord,’ she said, ‘it is good to see you back at Court. I trust you will stay.’

There was invitation there. Hervey considered it. She interested him, partly because she must be as different from his wife as a woman could be. Molly was as cool as April; this woman was hot August.

Her gaze was flattering: ‘You bring out the male in me,’ he said.

She laughed understanding. Hervey was an interesting character. Two-sided, it was said. There was the feminine side and the masculine. He liked this to be said. It made him seem so interesting. Although he preferred perhaps the company of his men friends, he was, he wanted people to know, not without interest in women.

‘We must talk together sometime.’

Anne Vane opened her mouth and let her tongue appear between her white teeth.

‘Some say there is no time like the present,’ she said. ‘And do you say it?’

‘On this occasion most emphatically? And my lord?’ ‘Slightly less emphatically.’

‘I am sure I should know how to make you more emphatic.’

‘And my Lord Harrington?’

‘Is spending a few days in the country.’

‘That must make you very sad.’

She smiled and laid her hand on his arm.

Hervey found Anne Vane an interesting mistress; and the liaison became more intriguing when Harrington returned. Hervey had no wish to make it known that he was Anne’s lover. Stephen became so jealous and there was always someone to carry such news.

He did not know what Frederick’s reaction would be either, for he and Frederick were drawing closer together every day and the Prince was beginning to tire of the apothecary’s daughter.

To please the Prince he suggested they should write a play together, and this delighted Frederick. Of course, thought Hervey, I shall do all the work; but it was worth it to have people saying that he and the Prince were becoming inseparable.

The play was difficult to write for he had never tried his hand at playwriting before. It required a more sustained effort than the writing of verses or the notes he was accustomed to make in his journal. He had his doubts as to the virtue of the play, but Frederick was enthusiastic about it. Poor Fred! He had no literary taste!

When the play was finished Frederick insisted on sending it to Wilks, the actor-manager at Drury Lane.

‘He must put it on the stage,’ cried Frederick. ‘No one shall know who wrote it. The King and the Queen will come and admire it and then and only then shall they know that the son whom they despise has some talents.’

Hervey regarded the Prince tolerantly. Did he really think Wilks would put on their little piece if he didn’t know the Prince had had a hand in it. Didn’t he see that the only hope of its ever being on a stage was because his name went with it.

But one must placate royalty, which often meant deceiving it.

‘You, my lord, will know exactly how to manage this. I want to go to the theatre and see our play.’

‘Leave it with me,’ said Hervey.

This Frederick was pleased to do, being certain that in a short time he and his dear friend would be sitting in a box incognito watching the audience delight in their work.