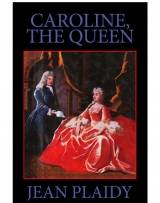

Текст книги "Caroline the Queen"

Автор книги: Виктория Холт

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

* * *

When the King wrote that he would not be back for his birthday, Walpole was seriously disturbed.

He came to see the Queen immediately.

‘This is the first time he has failed to come home for his birthday,’ he said. ‘He knows the seriousness of this. There will be comment and he does not care. This is significant.’

The Queen agreed that it was.

‘It means, of course, that he will not leave Madame de Walmoden.’

‘Then ...’ The Queen spoke almost sharply. ‘He must stay with her.’

‘Madam, if he does he will not stay King of England.’ ‘Then what ...’

‘There is murmuring in the streets already. He was never so unpopular as he is now. More and more people are looking to the Prince. I tell you this can be disastrous ... not only for the King, but for the House of Hanover.’

‘I know it,’ said the Queen.

‘There is a way out.’

‘Pray what?’ asked Caroline.

‘You must invite Madame de Walmoden to the Court.’

‘Invite her ... here?’

‘It is the only way. Here she will be to the King what Lady Suffolk was. It is the only way.’

‘I refuse,’ cried the Queen.

‘Your Majesty should consider the alternative. I would feel more comfort from knowing that woman was under our own roof than keeping the King in Hanover.’

‘I will not have that woman here.’

‘Doubtless Your Majesty will wish to consider this matter. We will talk of it later.’

* * *

When Walpole had gone the Queen went to her apartments and refused to see anyone.

This is too much, she told herself. I won’t endure it. It’s bad enough to read about her ... but to hear him talk day after day of her charms, of her reactions to his passion.... Oh, my God, I won’t have it.

She was surprised to find that there were tears on her cheeks. It is too much, she thought. Frederick, the riots, the unpopularity, Augusta’s pregnancy, real or trumped up, and this nagging pain, this awful forboding which envelopes me.

She covered her face with her hands and suddenly she was aware that she was not alone. She dropped her hands. Lady Sundon was standing watching her.

‘I ... did not send for you.’

‘I sensed Your Majesty needed me. May I help you to bed.’

The Queen felt suddenly defeated. There was no point in pretence now. Lady Sundon knew.

‘Come, come,’ she said, dropping ceremony and talking as though the Queen were a beloved but wilful child. ‘You should be in bed. Allow me to help Your Majesty.’

‘Oh, Sundon,’ said Caroline, ‘I’m so ... tired.’

‘I know, Madam. And ... the pain has been bad today.’

‘You knew.’

Lady Sundon went to her knees and kissed the hands. ‘I always know, Madam. My heart bleeds.’

‘Oh, get up, Sundon.’ She laughed. ‘It’s folly to lie to you. You know, don’t you?’

‘Yes, Your Majesty. I know.’

‘He knows ... Sundon. He knows too.’

‘His Majesty?’

‘Yes. He suspected long ago when it first started after Louisa’s birth. I told him it would pass. It often happens. He believed me. He wanted to believe me. He always wants to believe we are all well, Sundon.’

‘Yes, Your Majesty.’

‘And he never spoke of it again and I pretended that it was not there. Oh ... but the pain, Sundon.’

‘I know, Your Majesty.’

‘And then when he came home from Hanover he was aware of it. He mentioned it and I was angry... . So rarely am I angry with him that I alarmed him. I said he was tired of me, that he made this the excuse....’

‘Oh, Madam, Madam.’

‘He swore he wasn’t, that he never would be. But he is, of course, Sundon. He is. Why am I telling you this? Why ... why ... when I have kept silent all these years. You have known. The secret has been there, Sundon, all these years.’

‘But safe, Madam, I have never breathed a word ... never betrayed by a look.’

‘I know it.’

‘Nor will I ever without your permission.’

‘My dear, good friend.’

‘But I am afraid. The time has come when you should tell the doctors.’

‘Tell the doctors! Never. It has been our secret ... and so shall it remain. I should never have told you if you had not guessed. And thank you ... for keeping silent.’

‘Your Majesty, I would serve you with my life but I know there should be no more of this secret.’

‘There will always be this secret. Remember that, Lady Sundon.’

‘As Your Majesty wishes.’

‘Oh, what has come over me tonight. I am behaving like a fool. I talk too much of other things because I am wounded ... deeply wounded. The King will not be home for his birthday.’

‘Oh, no, Madam!’

‘Yes, it is so. He cannot tear himself away from Madame de Walmoden.’

‘Oh, Madam.’

‘So, Sir Robert Walpole thinks we should ask her here. The King will not live without her and it seems the House of Hanover cannot live as rulers of England without the King. It is all very simple, Lady Sundon.’

‘But Your Majesty will never receive that woman here.’

‘So I tell Sir Robert.’

‘I should think so! What next! How dare that man! He is so coarse and crude himself that he expects everyone else to be the same.’

‘He tells me that I shall change my mind.’

‘Your Majesty will not.’

The Queen looked sadly at Lady Sundon.

‘Help me to bed,’ she said. ‘I am utterly weary.’

* * *

When the King received the Queen’s letter inviting Madame de Walmoden to England, he was delighted.

‘You know well my passions, my dear Caroline [he wrote]. You know my weaknesses and that I hide nothing in my heart from you. How I wish that I could be more like you for I so admire you. How I wish that I could be good and virtuous like you but you know my passions and my weakness....’

My God, thought the Queen, so I do.

He went on to tell her how enchanted she would be with Madame de Walmoden’s beauty. She would quickly understand why he took such pleasure in this lady and she herself would be happy contemplating his happiness. He wanted her to have the lodging Lady Suffolk used to have. ‘That would be most convenient for me to visit her, my dear Caroline.’

Caroline showed Walpole the draft of the letter she had written to Madame de Walmoden.

He was delighted with it.

‘A masterpiece,’ he said.

‘A humiliating masterpiece,’ retorted Caroline.

* * *

It was impossible to keep secret the knowledge that Madame de Walmoden was coming to England. The Prince’s friends soon discovered it and decided to make the most of it.

It was discussed through the Court and the city. When is the King coming back?

Soon now. He has permission to bring the Walmoden with him. He was staying away until that permission was given. Now the Queen and Walpole are letting the little boy have his own way.

The people in the streets were less polite.

One morning the Princess Caroline, her cheeks flushed with rage, brought a paper into the room where her mother was having breakfast.

‘It was attached to the palace gates,’ she said.

The Queen read:

‘Lost or strayed out of this house a man who has left a wife and six children on the parish; who ever will give any tidings of him to the churchwardens of St James’s parish, so that he may be got again, shall receive four shillings and sixpence reward. N.B. This reward will not be increased, nobody judging him to deserve a crown.’

The Queen flushed slightly and went on drinking her chocolate.

* * *

The Prince of Wales riding in his carriage through the city with the Princess saw the crowd gathered round an old horse with a dilapidated saddle on its back.

He stopped his coach and asked if there had been an accident.

When he was recognized he was cheered, for the people wanted to show him that anyone who was an enemy of the King was their friend.

Then he saw the notice attached to the horse.

‘Let nobody stop me, I am the King’s Hanoverian Equipage going to fetch His Majesty and his whore to England.’

The Prince read this in a loud voice and laughed heartily at which the people cheered him more than ever; and they followed him back to St James’s shouting, ‘God Bless the Prince of Wales and let his father stay in Hanover’.

Caroline was disturbed by these public demonstrations of disapproval.

‘What will happen when the King sets foot in England with that woman?’ she demanded. ‘There’ll be a revolution.’

‘Have no fear,’ smiled Walpole. ‘She’ll never come.’ ‘But ... you suggested I should ask her.’

‘Ask her by all means, but I have a strong feeling that she will not come. My brother has always been of the opinion that she would not come.’

Walpole was smiling. It had been a wise move to send his brother, Horace, to Hanover with the King. He was sure then of hearing all he should know.

‘She’s no fool, this Walmoden. She realizes that her position as the Lady of Hanover to be visited as a special treat puts her in a far happier position than she would be in if she lived in this country. My brother tells her of the life poor Lady Suffolk led. She wants none of that. No, she will find excuses when the time comes. Your Majesty will never have to receive Madame de Walmoden in England.’

‘I hope you are right,’ said the Queen. ‘I admit to profound relief. And if she will not come, what of the King. Will he decide to stay with her?’

‘That is something he cannot do. He will have to return very soon.’

* * *

The King continued to postpone his departure; but Madame de Walmoden as Walpole had said, found excuses for not coming to England. She assured him of her fidelity; he must promise to return to her soon; but she could not come to England. She felt that it would jeopardize the King’s position if she did. That, she declared, was her sole reason.

In vain did the King plead. She was determined. She would not imperil his crown; rather would she grieve for him in Hanover and hope and pray that he would soon return to her.

The King gave a farewell ball and then another and another.

December had come and he was still in Hanover.

The Queen wrote to him that she had alarming news of Anne, the Princess of Orange, who was preparing for her confinement which threatened to be a difficult one. Perhaps he would call at the Hague on the way back. He would still have time before the weather became too bad.

But the King could not bear to leave Hanover and he gave another farewell supper and by that time it was the 7th of December and he dared not delay longer than that. for in a few weeks the weather could grow so bad that he might not be able to leave until the spring.

The Queen waited for his coming, for she had now heard that he had definitely left Hanover and once he had she knew he would travel with all speed.

* * *

The weather turned stormy and the wind howled through the Palace. News came from the coast towns of storm damage; but there was no news of the King.

Caroline was alarmed. If he had put to sea he might well be drowned, for how could any ship survive in the storms which were sweeping the seas?

The King’s name was on every lip throughout the country. Where was he? Why was there no news of him? He must be drowned ... drowned coming from his whore, said the people, with all his sins on him.

The Prince of Wales showed no regret, but he gave himself airs; he was receiving more attention than he had ever received before. The general opinion was that he was in fact no longer Prince of Wales but King of England.

The Princess Amelia went about tight-lipped. If Frederick were King there would be changes. The Princess Caroline frankly declared her horror. This was the worst thing that could possibly happen to them. Fred would have no respect for any of them. He would humiliate them in every way he could think of ... particularly Mamma. William was making secret plans, wondering how he could discredit Fred and take the throne from him.

And the Queen waited for news and thought of him, the little man who had lived so close to her for so many years, who had snubbed her and bullied her and had declared always that he loved her. What would she do without him? Did she love him? How could she love one who humiliated her as he did, who so recently had planned to subject her to the greatest humiliation of all, who told her the intimate details of his love affairs because he believed she loved him so much that she was delighted to hear them? He was obtuse; he had no love for the things of the mind which once had been so precious to her; he was a silly little man, a bad-tempered, vain, little man—and yet to lose him would be like losing part of herself.

* * *

The Prince of Wales came to see the Queen.

He could not hide his delight, so she knew he brought bad news.

‘I have a letter which I think you should see, Madam,’ he said. ‘It is from a friend at Harwich who a few days after that when we believe the King must have set sail, heard distress signals fired at sea. There can be no doubt that these came from some ships of the King’s fleet.’

‘There must have been many ships at sea on that day,’ said the Queen, reading the letter.

‘Not many, Madam. I am convinced that this was one of the King’s fleet and that we must reconcile ourselves to his loss.’

‘I do not think—in that unhappy event—you will have much difficulty,’ said Caroline coldly; and she turned away indicating that the interview was at an end.

* * *

But by the end of that day a messenger arrived with a letter from the King.

The messenger had been several days at sea in a fearful storm, but the King wanted the Queen to know that he had not set sail as arranged and was awaiting a good wind at Helvoetsluys.

The Prince’s discomfiture was as obvious as the Queen’s delight. But the position was very quickly in reverse, for no sooner had the King set sail than a storm came up more violently than ever and now there could be no doubt that the King was drowned.

But yet again came the news that although the King had set sail his Captain had prevailed on him to go back to land when the storm threatened and the King had reluctantly allowed himself to be persuaded.

Thus he still lived though the sea parted them.

So overjoyed was the Queen when she heard this news that she wrote to him and told him how she had suffered through her fears that she had lost him. The King, always responding to sentiment, wrote a long letter to her—a passionate love letter, for the first time omitting any mention of Madame de Walmoden. She was the perfect wife; for her he had love which was all her own and could never be shared by any other person. She was his perfect Venus; and the reason he had allowed the Captain to overrule him was because he could not risk the chance of never seeing her again.

When Caroline read the letter she wept with joy. It was the kind of letter he had written in the days of their courtship, for he had always loved to pour out his sentiments on paper.

She could not resist showing it to Walpole who had told her so bluntly that she could no longer hope to appeal to the King’s senses.

Walpole smiled cynically. He knew his King, and he was not surprised that the dramatic circumstances had produced such an epistle. Still he was ready to concede that it was a good sign that the King could still write so to his wife.

Now there was the King waiting for a fair wind at Helvoetsluys and the nation was caught up in the drama, as it so liked to be.

‘How is the wind with the King?’ was the catch-phrase of the day.

And the answer was : ‘Like the nation, against him.’

In time the wind turned favourable and the King immediately set sail.

It was mid-January before he reached England and more than eight months since he had left.

The Queen, with all the family, were waiting to welcome him in the courtyard as his coach trundled into the Palace.

Even the Prince of Wales was there, but there were only cold looks for him. The King had eyes for no one but the Queen and with tears in his eyes he embraced her with the utmost affection that all might see in what love and devotion he held her.

Accouchement at Midnight

‘THE King is dying!’

This was the theme of conversation in the Prince’s apartments. The change in Frederick was being noticed and many people who had followed the King’s habit and ignored him, now found him worthy of their attentions.

It would not be long, it was said, before the Prince of Wales was King.

George had returned from Hanover this time in a very different mood from last. The irritable temper flared up now and then, it was true, but it was mingled with moods of subdued affection towards his wife. Whenever he mentioned her, tears filled his eyes and he said again and again that she was the best wife in the world.

He did not mention Madame de Walmoden and Walpole wondered whether that little affair had come to an end; but according to his brother, Horace, the King’s farewells to his mistress had been as touching as ever and he had sworn to return to her; and when it was considered that he had delayed leaving her so long that he had not had time to see his daughter who was, it had been thought, at the point of death, it was strange that he should have forgotten his mistress.

The fact was that the King was ill. The trying journey had had its effects on him and he suffered as well from all the depressing ailments which attacked him intermittently.

In fact when it was believed he was with the Queen he was actually keeping to his bed. He would get up, dress for a levee, and come back to bed, so anxious was he to keep the state of his health from his subjects.

Walpole asked the Queen to tell him the truth about the King’s condition, and she replied that the journey had been too much even for him and he was merely feeling the consequences of it; but the minister was not entirely convinced; and as he believed the King to be suffering from some malady about which he had forced his doctors to be silent, he was forming all sorts of conjectures.

The King saw that the Queen was anxious and wanted to know why.

She told him that Walpole was suspicious and thought he was suffering from some fatal complaint.

When he heard this George got from his bed and insisted on dressing.

‘You should not do this,’ cried the Queen. ‘You know you need to rest.’

‘You know who is putting these rumours about. It’s that young puppy. He thinks he is King already. I will show him.’

The King appeared that evening and played quadrille. Lady Deloraine sat beside him and the King paid her marked attention.

‘He looks very wan,’ said the Prince’s friends. ‘And what a lot of weight he has lost.’

But George had made up his mind. He was going on with the old routine; and night after night found him at commerce and quadrille, and he was quite clearly showing a very purposeful interest in Lady Deloraine.

He seemed to recover from that night and grow gradually better. He was soon his old self, giving vent to outbursts of temper, flaying everyone within sight with his tongue if they angered him, and visiting Lady Deloraine.

The Prince was disappointed. He had really thought that the King was in decline and that he himself would be crowned within the next year.

He was sulky. It was unfair. First he had been led to believe his father was drowned; then that he was dying; and now here he was as perky as ever—and as maddening.

He deplored the fact that Bolingbroke had deserted him to go and write in France. He had powerful friends in England though. There was Pulteney of course, and Carteret, and men like young Pitt and Lyttleton, and of course Chesterfield.

He summoned them to his apartments to talk seriously of what could be done.

‘I’m Prince of Wales. I am nearly thirty. I am married ... perhaps soon to become father to the heir of the crown ... and I am treated like a child. I tell you, gentlemen, I shall not endure this much longer.’

Pulteney had realized that it was concerning this matter that the Prince had called them together. In fact it was continually on the Prince’s mind. He wanted the £100,000 a year which his father had had when he was Prince of Wales and since that amount had been taken into consideration when compiling the Civil List, this did not seem unreasonable. He wanted a dowry for Augusta—and if the Opposition made sure, through their writers, that the people know how the Prince had been cheated of these things by his father they would all be in favour of the Prince.

The King had been at the height of his unpopularity when he was in Hanover with Madame de Walmoden, and although he had regained a little regard by running the risk of drowning he was still heartily disliked by his people.

Pulteney saw that the Opposition could bring discomfort to Walpole’s ministry by bringing up this matter of the Prince’s allowances and at the same time win the Prince’s approval, and as it was not at all unlikely that the Prince would be King, possibly in the near future, only good could come of it, for once the King died the Queen’s power would die with him. It was quite clear how the Prince regarded his mother.

Pulteney therefore declared that with the support of his friends he would bring up in Parliament the question of the Prince’s allowances.

* * *

When Walpole brought the news to the King and Queen they were furious.

‘We could,’ said Walpole, ‘suffer defeat on this.’ ‘The young puppy! ‘ bellowed the King.

‘These disputes will kill me,’ murmured the Queen. Walpole lifted his shoulders. ‘We must face the facts,’ he said. ‘The Prince has a case.’

‘You are the Parliament,’ shouted the King. ‘You have insisted on having your way in some things ... and now on this you say you’ll be defeated.’

‘I have a very small majority now, Your Majesty will remember. Perhaps we could compromise. If Your Majesty would offer the Prince £50,000 a year and give the Princess a dowry ... and offer this before the motion comes on in the House ... he might accept it. It would be better than what he is now demanding and what may well be assigned to him.’

The King swore he wouldn’t and cursed the Prince, Walpole, and the government. They were all a lot of boobies.

But the Queen prevailed upon him to write to the Prince as Walpole had suggested—an effort which misfired, for the Prince was certain of success.

Walpole was his brilliant self in the House. He told of the King’s wish to live on good terms with his son, of his offer which had been rejected; and he stressed that this was more than a dispute between a father and son; this was trouble in the royal house, something which could affect the nation. So did he sway the House that the Prince’s claims were rejected.

Walpole himself went to the Palace to tell the King and Queen of their victory.

George was delighted.

‘You are a man of spirit,’ he told Walpole. ‘What the Queen and I should do without you, I do not know. As for that young puppy, I’m going to tell him to get out of my house. I’ll not have him in St James’s. He can leave with his wife at once.’

‘Your Majesty,’ cautioned Walpole, ‘that would be a most unpopular move. It would be remembered how the King, your father, behaved to you—and you know what unpopularity that brought him.’

‘This is different. I was ready to be a good son, whereas this young puppy ...’

‘I wish he had never been born,’ said the Queen. Walpole sighed. ‘Your Majesty should now make good

your promise and without delay make arrangements for

the Prince to receive the £50,000 you promised him.’ ‘I see no reason why ...’

‘Your Majesty, there is every reason....’

‘I see none. I see none.’

Walpole left the King in disgust and dismay; he knew that he had to be brought round to his point of view.

* * *

The Prince was not entirely downcast to have lost the support of the Commons, for his friends, led by Chesterfield, promised to bring up the matter in the House of Lords; this they did and although here they were defeated again it was by a small majority and it became clear that public opinion was on the side of the Prince.

Walpole enlisted the support of his ministers to force the King to keep to his bargain and make the allowance he had promised.

The King was furious. ‘The motion has been defeated by the Parliament,’ he insisted.

‘But only, Your Majesty, because of your promise to meet the Prince half way.’

‘Half way! Half way! ‘ cried the King. ‘That is it, this government is too half-hearted.’

The Queen, who to Walpole’s surprise was not on his side, added her voice to the King’s and murmured that if the Whigs could be so little depended on, it might be time to see what the Tories could do.

This shook Walpole, because his majority in the house was so small and he knew that it would take very little to bring him to defeat, and that would mean the defeat of the Whigs, and a Tory ministry.

Moreover he knew that Lady Sundon’s influence with the Queen was growing stronger, and Lady Sundon had always been his enemy.

Lord Hervey, Heaven knew, was deep in her confidence, but Walpole believed Lady Sundon had some hold over the Queen which even Hervey knew nothing about.

It was an anxious time. And of course soon they would be hearing that the King wanted to go to Hanover, for although he did not mention Madame de Walmoden, he was still writing to her; and Walpole had reason to believe that he was as much enthralled as ever by that woman.

In fact the Queen had no intention of breaking her alliance with Walpole. She respected and admired him too much; but she thought there was no harm done in letting him believe that unless he supported her and the King with all his power she was dissatisfied with him.

‘There is one good thing which has come out of this trouble with the Prince,’ said Walpole to her one day.

‘I can see nothing good in anything the Prince does,’ replied Caroline.

‘He is restive; he is ready to take strong action should the opportunity be offered to him.’

‘What opportunity?’

‘If the King should go to Hanover. I foresee fatal consequences if the King left the country at this time.’

This was a matter in which the Queen and her minister were in complete agreement.

Oddly enough, strong as was the desire to be with his mistress, the King saw the point of this too.

The Queen was in her apartments when a letter was brought to her from the Prince. The sight of his handwriting always displeased her and hastily she read its contents, wondering what fresh trouble this might mean.

As she read she was saying to herself: ‘I don’t believe it. It’s a lie.’

She threw the letter on to the table. The Princess Augusta pregnant. There was no doubt about this, wrote the Prince, and he hastened to tell his mother the joyful news.

Joyful news indeed! He had his income; he had his wife; and now they were going to produce a child.

She went to the King and said she must speak to him alone.

Then she showed him the letter; his eyes blazed with anger.

‘It is a lie. He is incapable of getting children. He is an insolent, lying puppy! ‘

‘Do you think this is a plot to foist a spurious child on us?’

‘It is such a plan,’ declared the King.

‘It could well be. I have thought the Prince to be impotent. FitzFrederick was Hervey’s. “Why,” I said to Hervey, when Molly Lepel’s young William was presented to me ... “that could be FitzFrederick’s twin.”’

‘It’s a plot ... and it shall not succeed. I will command that he and the Princess live under our roof and we will see the progress of this pregnancy.’

‘And I shall be present when the child is born,’ declared the Queen. ‘I shall not allow William to be done out of his rights.’

The Prince knew what was said of him and jeered at his parents. They wanted to pass him over in favour of that insufferable brother of his. Well, thank God the English people were behind him and he was not surprised at that, for he had always loved England. He was not like his father running off to Hanover at every possible moment and declaring his dislike of everything English. The Prince could not understand why the English tolerated such a King.

He disagreed with everything the King said and did. Augusta, the meek little wife, supported her husband. He was the best husband in the world, she declared; and when the time came—and every right-thinking man and woman in England prayed that time would not be long in coming —he would make the best King in the world.

‘My child shall be born in St James’s Palace,’ declared the Prince. The Princess and I have made up our minds about that.’

‘The child shall be born where I am at that time,’ declared the King, ‘and as it will be summer that will be at Hampton Court.’

‘I say St James’s Palace,’ said the Prince.

‘I say Hampton Court,’ retorted the King.

The Queen’s comment was: ‘Wherever it is I shall be there. I am going to see the entry of this child into the world.’

* * *

The Court was at Hampton for the summer and the Prince and Princess were obliged to have their apartments there.

On those occasions when the Prince had to be in the company of his father, the King behaved as though he didn’t see his son; and the Prince declared again and again that he resented his parents’ attitude; and as for his mother’s being present at the birth, he was determined she was not going to be and he was as insistent that the child would be born at St James’s as they were it should be born at Hampton.

‘In this,’ he said to Augusta, ‘they see a symbol. Heirs to the throne should be born at St James’s and they want to pretend even at this late date that our child will never ascend the throne and that it will go to that dreadful William—on whom they dote.’

‘You are right, Frederick,’ said Augusta.

‘And I am going to outwit them.’

‘How?’

‘You will see. Leave everything to me.’

‘Oh, yes, Frederick.’

‘All you have to do is as I say. By September I shall have you installed in St James’s, never fear.’

* * *

The Prince was with his friends on the last day of July when one of the Princess’s women came hurrying into the room in a state of agitation.

‘Your Highness,’ she said, ‘please come at once to the Princess.’

Frederick hurried to his wife’s apartments to find her sitting on the bed looking frightened.

‘My pains have started,’ she said. ‘What shall I do?’ ‘It can’t be ... it’s two months too early.’

‘But Frederick, I’m sure ...’ She broke off to cry out.

One of the women said: ‘The pains are coming fairly frequently, Your Highness. That means that the baby will soon be born.’

‘Not here,’ cried Frederick. ‘Not here at Hampton.’ ‘There is no help for it, Your Highness.’

‘But there is,’ cried Frederick. ‘Have the coach made ready. We are leaving without delay for St James’s.’