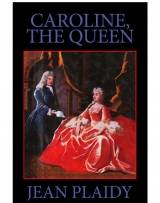

Текст книги "Caroline the Queen"

Автор книги: Виктория Холт

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

‘Which reminds me,’ put in Anne, ‘our eldest brother will soon be here. They’re bound to send for Fred.’

‘Fred!’ mused Amelia. ‘I wonder what he’s like.’

‘A horrid little German, you can be sure.’

‘Well, he has spent all his life in Hanover.’

‘Poor Fred!’ sighed Caroline. ‘They call him Fritz over there.’

‘I’ve no doubt he’s a regular little Fritz.’

‘You must not make yourself hate him before you sec him, Anne,’ warned Amelia.

‘I don’t have to make myself. I do already.’

‘But why?’

‘Imagine him. He was seven years old when Papa and Mamma left Hanover and they haven’t seen him since.’

‘What would he be now?’ asked Caroline.

‘Over twenty ... nearly twenty-one,’ said Anne. ‘He’s two years older than I.’

‘Do you remember him, Anne?’

She narrowed her eyes. ‘Yes, I think I do ... a little. He was very spoilt. He had rickets for a long time and couldn’t walk ... but that was before I was born. They called him Fritzchen and it was quite sickening the fuss they all made of him.’

‘So you were jealous?’ asked Amelia.

‘Of course. I wanted to be the eldest ... and a boy ... so that in time I could be Prince of Wales. Then Queen Anne died and Grandpapa came to England and after a while Mamma brought us girls, but Grandpapa wouldn’t allow Fritzchen to come. He had to stay behind and look after Hanover.’

‘What, at seven?’ asked Amelia.

‘He was a figurehead. Grandpapa was quite fond of Fritzchen, which is saying something, for he wasn’t fond of anyone else ... except the poor old Maypole. I wonder what she is doing now.’

‘I’m sorry for her,’ said Amelia. ‘It must be terrible to be a king’s mistress and be important and then suddenly he dies ... and nobody cares about you any more.’

‘Don’t worry about her. She looked after herself very well, I’m sure.’

‘I wasn’t thinking about money. It’s rather strange that a man like Grandpapa could be faithful to a woman like that—for all those years. And she was terribly ugly too. I heard she was almost bald under that awful red wig.’

‘He wasn’t exactly faithful. That reminds me. Mistress Anne Brett must be feeling very sorry for herself. Do you know she threatened to speak to Grandpapa about me because I wouldn’t allow her to alter the arrangement of this palace. What is she thinking now, do you imagine?’

‘She’s busily packing and preparing to leave, I’ll swear,’ said Amelia.

Anne threw back her head and laughed. Caroline did the same.

‘It’s a small matter,’ said Amelia. ‘Scarcely worth feeling triumphant about. The point is that everything will be different for us. Our parents will come here ... we shall all be together. Instead of being two separate families, there’ll be one. The family will be reunited; we shall be with our little brother and sisters. And Fred will most certainly come home.’

‘When?’ asked Caroline.

‘Very soon. After all he is Prince of Wales now. Fancy that! Fritz who has never set foot in England is Prince of Wales.’

‘I know why you hate him,’ said Amelia. ‘You would like to be Prince of Wales.’

‘How could I be?’

‘You could be Princess of Wales,’ said Caroline. ‘And if there were no boys ...’

Anne stood up and raised her eyes almost ecstatically to the ceiling.

‘Do you know,’ she said, ‘if I could be Queen of England, if only for one day, I’d be willing to die the next.’

‘Anne!’

‘It’s true,’ she declared. ‘And I’m sure I’d make a better ruler than Fritz ... or Papa ... or Grandpapa. There was a Queen Anne of England. I was named after her. They call her good Queen Anne.’

Amelia stood up. ‘Listen. You can hear the sound of trumpets. Papa and Mamma are passing through the city.’

The girls were silent, listening.

* * *

Sir Spencer Compton came in all haste to Chelsea. He was a worried man. Greatly as he appreciated the honour the King had done him, he was a little uncertain of his ability to hold the high office which was being thrust upon him, and now right at the beginning of his new duties he was confronted by a task which he was incapable of performing, and he feared he was going to show not only the King but the whole Court that he could not compare with Walpole.

It was the simple matter of the King’s Speech which it was his duty to prepare and he had no idea how to do it.

There was one man who knew exactly what should be said and what left unsaid; that man was Sir Robert Walpole.

Walpole had, when informing him that the King had dismissed him and told him to take his orders from Sir Spencer Compton, assured the latter that he would be willing to help in any way possible. Well, here was a way in which he could help.

‘I have come,’ said Sir Spencer, ‘to ask you to write the King’s Speech, because for the life of me I have no idea how it should be done.’

‘Leave it to me,’ said Walpole. ‘I will do it immediately and it shall be in your hands in good time.’

‘I am indeed grateful,’ Sir Spencer told him.

When he had gone Walpole went to work on the speech, amused and gratified that his services should be so quickly needed; but there was a desolation in his heart, for he was already realizing how much power meant to him and he felt deeply depressed because it seemed that he had lost it forever.

Even in the streets they would already be talking of his fall. He was not so clever as he had thought he was. He had been so sure of himself that he had neglected to fawn on the Prince of Wales and the Prince of Wales was now King. He was not sure of the new Queen; he had displeased her now and then, but she was too clever a woman to bear long grudges and in the last years they had appreciated each other.

But the King had dismissed him. And even though the new favourite had to ask his help the cry had gone up; it was echoing throughout the Court and the city: Walpole is dismissed.

* * *

There were so many things to be done, thought the Queen, as she sat before her Mirror and Charlotte Clayton with Henrietta Howard loosened her hair and unbuttoned her gown, to give her greater comfort.

The girls must be brought into the family again, and Frederick must come home. She used to think of him as Fritzchen, but that was long ago. It must be years since she had ceased to think of him at all. Indeed since young William was growing into such a charmer she had almost wished that her firstborn had never existed. What would he be like after all these years? He would be like a stranger . . . a German stranger.

But that could wait. Even the girls could wait awhile. There were more pressing problems.

‘How I hate this bombazine!’ she sighed.

‘It is quite becoming to Your Majesty,’ Henrietta told her.

Caroline eyed herself. Yes, Henrietta was right. The black showed up the fairness of her skin and the magnificence of her shoulders and bust—that bosom which George Augustus declared was the most beautiful in the world.

But this was no time to be thinking of what she looked like. There were important matters to be dealt with and the most important was that the King should not act foolishly now that he had ceased to be the Prince who was of no account because it was his father’s wish that he should not be.

She could see fearful pits yawning at their feet. The situation in Europe was very tricky; and there was one man who was so well versed in foreign affairs that they would need him; that was Sir Robert Walpole. There was one man who could keep the government steady; and that was Walpole.

In fact, thought Caroline, he is crude and uncultured, his morals are questionable; he is ugly and too fat; he drinks too much; he is not exactly a charming man; but he is the man we need.

She thought of the King’s delight when he had come to tell her how he had dismissed Walpole. ‘I have said to him: “Your orders you vill take from Spencer Compton.” He vas scarcely off his knees ven this I tell him.’

And she was expected to applaud such promptitude, such sly action, such a neat way of paying off old scores, when she wanted to shout: But we need this man. He is the only one clever enough to help us. If he does not work for us he will work against us.

But one did not presume to advise the King; she never had done that to the Prince of Wales. And yet how often had she persuaded him—in such a manner that he was unaware of it, of course—to decide on what she had already decided.

Tonight he would preside over his Accession Council; he must not make it known during the meeting that he had dismissed Walpole. But Henrietta had told her that Sir Spencer Compton was already being treated with homage and that Walpole was being ignored.

Something would have to be done. She wondered how she could do it.

Her woman, used to her pensive moods, worked silently; they were doing her hair when the King came in. He was dressed for the Accession Council meeting and he sat down heavily in the chair which Henrietta hurried to place for him.

‘Ha, my tear,’ he said, looking affectionately at his wife, ‘I see you are looking very beautiful ... as beautiful as a queen, eh?’

‘And you look like a king.’

‘Ve must grow accustomed to looking so.’

He smiled at the two women and his gaze lingered on Henrietta. She is getting old, he thought; now that I am King perhaps I should choose new mistresses. I should not continue with a woman who is no longer young.

He scowled. ‘Vy haf you covered the Queen’s neck?’ he demanded. ‘Is it because you haf not a beautiful neck that you must cover the Queen’s?’

He snatched the scarf which was about Caroline’s shoulders.

‘There. That is better. Now ve see this beautiful neck.’

Caroline nodded dismissal to the two women and they went quietly out.

‘This is a most important meeting,’ said Caroline. ‘The Council vill be assembled to hear your speech. You vill have it by now.’

‘No, I have it not.’

‘But ...’

‘It vill come. It vill come. Compton is von good man.’ ‘I hope he can write as good a speech as Valpole.’

‘That fat old fox. I tell you he is von scoundrel. You should have seen his face. It came out so neatly. You vould haf laughed.’

No, thought Caroline. I should have groaned.

‘Veil, the speech should be here.’

‘You should not vorry, my dear. Ah, I think it comes now.’

The King’s page had appeared to say that Sir Spencer Compton was in the King’s antechamber.

‘Bring him here,’ commanded George.

Sir Spencer came in with the speech which Walpole had just brought to him.

The King read it aloud.

‘It is vith great sorrow that I hear of the death of the King, my dearest father ...’

George grimaced. But of course it was what was expected of him. He must pretend to mourn; although the gaiety of his expression would surely belie that.

‘My love and affection is for England and I shall preserve the laws and liberties of this kingdom. I shall uphold the Constitution ...’ Yes, this was what they wanted to hear.

Caroline came and looked over the King’s shoulder as he read; Compton watched them with relief. He was very uneasy; he knew he was unfitted for the task; he was no Walpole. It was only due to the latter’s help that he had extricated himself from a difficult situation in the first hours of his new office. Suppose Walpole had refused to write the speech!

The King was saying, ‘No, this vill not do ...’

Compton started. ‘Your Majesty does not like the speech?’

‘It is yell enough. It is vell enough. But this must be changed. Change it now.’

‘What ... what does Your Majesty wish to say?’

‘I do not know. It is for you. Do it now. The women vill give you a table and chair ...’

‘Your Majesty, it would be a great mistake to change the speech.’

‘Vat is this?’

‘Your Majesty, the speech should remain as it is.’

‘But I say this is not goot. This paragraph ... he must be changed.’

‘It would be better to leave it as it is.’

‘Better. But I say this vill not do.’

Compton was bewildered. How could he change the speech? It was Walpole’s work and he could not imagine what might be substituted for the offending paragraph.

‘I ... I will take it away, Your Majesty,’ said Compton. ‘I will need to do this.’

‘Then do not be long. I must haf it ... soon.’

When he had bowed himself out, the offending speech under his arm, the King looked at the Queen. She was examining the stuff of her gown; she dared not look at the King for fear she betray a certain triumph. It had occurred to her that the King was going to see that he had acted rashly.

It was only a short time later when they heard that Walpole was asking for an audience.

‘This I vill not give,’ said the King. ‘I haf not the time. Vere is this speech. Vat has happen to Compton?’

‘It may be that Valpole hav come about the speech ...’ began the Queen, an idea occurring to her.

‘How is this?’

‘If you thought fit you might permit him to come. There could be no harm.’

The King looked at her in a puzzled fashion and then said he would see Walpole. Caroline was inwardly exultant when she saw that Walpole was carrying the speech.

‘Vat the ...’ began the King.

‘Your Majesty. Sir Spencer Compton has asked me to adjust the paragraph of which you do not approve.’

‘But vy ...?’

‘Your Majesty, I had written so many speeches. Sir Spencer so few. And so ...’

‘You wrote this von, Sir Robert?’ asked the Queen. Their eyes met. It’s not too late, thought Walpole. She is with me.

‘I wrote it, Your Majesty. The need for haste ...’

‘Yes, yes,’ said the King testily. ‘Let us see this paragraph.’

The Queen read it with him. am sure the King vill say that is vat vas needed,’ she said.

‘It is vat vas needed,’ said the King gruffly.

Walpole bowed his head; he stood before the King and said: ‘Your Majesty, if I can serve you in any way ... in or out of office, you may depend upon me.’

‘I shall remember,’ said the King, and turned away. Again a look was exchanged between the Queen and the minister. Walpole bowed and went out.

The King was annoyed.

‘I do not like this man,’ he said.

‘He drinks too much,’ agreed the Queen.

‘He is von big fat ox.’

‘His conversation at table is most coarse.’

‘It is yell he is dismissed.’

‘It is ell if ve can find better men than he.’

‘Vat you mean?’

‘There is much to be done. Perhaps you vill not vant to hurry to make a new ministry.’

‘I am tired of this man. He takes bribes. He is von greedy old rogue.’

‘There will be other greedy rogues. He must be rich by now. Perhaps Your Majesty will say that others less rich might be more open to bribes.’

‘Vat is this?’

‘Old leeches are not so hungry as young ones . . . it is often so.’

The King looked at his wife for a few moments and she said quickly: ‘It may be that Your Majesty vill think so. May I look at your speech?’

She read it through and he continued to watch her.

‘It is good,’ she said. ‘That sly old Valpole wrote it. I know his style.’

‘He is von fat old leech,’ said the King; and the Queen laughed immoderately.

He was pleased; but he was also thoughtful. Perhaps, he was thinking, he should not be too hasty.

The Late King’s Will

THE new King, his speech in his hand, entered the council chamber where his ministers were assembled.

George noted with pleasure the new deference they accorded him. They were wary too, a little apprehensive, wondering whether in the past they had sided too openly with his father against him.

I shall not forget! George gleefully told himself. They shall regret their mistakes.

Already Walpole was regretting. He had heard the fellow only had to enter a room and all backs would be turned on him. Now he must be wishing that he had remembered that a Prince of Wales, however out of favour with the reigning monarch, in turn becomes the King.

He acknowledged their homage and read his speech of regret for his father, and if any of them felt like tittering they made no sign but composed their faces into attitudes of respectful melancholy.

He went on to say how he loved England and how he intended to devote himself to the service of his country.

It was the speech of tradition—no better, no worse than its predecessors, but it had the virtue of being what was expected and was greeted with applause.

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Wake, was a timid man who was a little unsure of his position, having been completely submissive to the previous king, and anyone who had been so must almost inevitably be on bad terms with the new one. But Dr Wake had contrived not to offend the new King while being on good terms with his father. In any case such a man made little trouble and George’s feeling for him were neutral.

He now approached the King and put a document into his hands.

‘Your Majesty, this is your father’s will which he entrusted with me, asking that I would present it to you on the event of his death. This I now do.’

George looked at the document. A will! The old scoundrel had decided to outwit him at the end. Who knew ‘what was in that document. He could be certain though that it would be something to cause embarrassment to the son he had hated.

His ministers were watching him expectantly. The Archbishop was holding the will. Clearly he was awaiting the formal command to open it and make its contents known.

Everything was according to the tradition which had been followed through centuries. Now was the moment to read the late King’s will.

But his son held out his hand for the document, scarcely glanced at it, and thrust it into his pocket.

‘Now,’ he said gruffly, ‘ye have some business to discuss.’

The Archbishop was astounded; the members of the Council could scarcely believe what they had actually seen; but the King was testily waiting to continue with the meeting, as though the will was of no importance to him.

* * *

The King made his way to the Queen’s apartment, and as soon as he entered she recognized that he was deeply disturbed, so she dismissed her attendants and waited patiently for the outburst.

He was not as choleric as usual, which might be a bad sign, for it could mean he was too disturbed for an outward display of anger.

He stood for some seconds rocking on his heels, his face which had been pink when he entered growing red; his blue eyes seeming to bulge more with every passing moment.

Still she did not speak.

Then slowly he took a document from his pocket and held it before her eyes.

‘The old scoundrel’s vill,’ he said.

He saw her catch her breath; he saw the faint colour touch her face and neck. There was no need to explain to Caroline the importance of this paper.

‘Vat does it contain?’ she whispered. Wild thoughts were running through her mind. He would pursue them even after death. Did they think that they were rid of him? That document could deprive them of their inheritance. But could it? George Augustus had already become George II; would it be possible for the old man to have his grandson Frederick substituted for his son? Frederick! The son for whom in the past she had so longed and had now almost forgotten—because the old scoundrel had decreed that they should live apart. No, not that. But it was certain there would be something to plague them in that will. Money they needed would be directed elsewhere. The Duchess of Kendal would be given a large part of the wealth which by right belonged to the King and Queen of England.

She was watching her husband anxiously, and he shook his head while a slow smile of triumph spread across his features.

‘No one living knows. Let him keep his secret. He is dead now.’

‘But ... surely it was read at the Council?’

There was pride in his face. He was the King now; he would know how to rule and no one should be allowed to forget that.

‘I did not ask it to be read. I took it when Vake gave it to me and put it into my pocket.’

Now she was smiling—approval, admiration. How he loved her! They would stand together against all their enemies.

‘And they said nothing?’

‘To the King!’

Then she laughed. ‘No, of course, they vould not dare ... not to the King. And now?’

‘You know vat he did to my mother’s vill?’ demanded the King. ‘Do you think she vould have left all she had to him ... her enemy? Do you think she vould have forgotten me and my sister? She loved us alvays. Ven my Grandmother Celle visited her the first thing she wanted to know was “How is my son George Augustus? How is my daughter Sophia Dorothea? Are they yell, are they happy?” And she was rich. Vat did he do vith her vill? He destroyed it. Vat did he do vith the vill of my Grandfather Celle which you can depend left much to me and none to him? He destroyed it. And now vat shall I do vith his vill, eh? I tell you this. I shall treat him as he treated others.’

The King went to a lighted candle and held the document in the flame.

For a few seconds it seemed as though it refused to burn; then the thick paper suddenly leaped into flame.

The King smilingly watched it until he could hold it no more; then he threw it into the fireplace and together he and the Queen watched it blacken and writhe until there was nothing left but the charred remains.

* * *

The King was peevish. The Queen understood why and was not displeased. Secretly she was determined to set Walpole back in his place for she realized that the imperative need of a king such as her husband was a strong government. There was one man she wanted to see at the head of that government and that was Walpole.

‘Walpole, that fat old ox!’ cried the King every time his name was mentioned. Then she would laugh and agree that he was a fat old ox; she would admit that he had not fulfilled his promises to either of them; but in her heart she knew that they must not harp on old grievances; they needed the most able statesman in the land to head their government and that man was Walpole.

She came to her husband’s apartment and when they were alone she asked him how Compton was acting with regard to some of thc important matters which needed prompt settlement.

George scowled. ‘It is delay ... delay ...’

‘The Civil List is the most important. Perhaps he does not delay with that.’

George’s face grew red; his hands went to his wig. He did not snatch it from his head, she noticed, which had been a favourite habit in the days when he was Prince of ‘Wales, stamp on it, and kick it round the room; kingship had given him some dignity.

‘He vants me to accept vat my father had. And I have this big family.’

‘It vill not do.’

‘This I tell him. But he say the Parliament vill not agree.’

‘They must be made to see ...’

‘They vill. I shall insist.’

He drew himself up to his full height and inwardly Caroline sighed. The little man must know in his heart that he could not stand against his Parliament.

‘They vill give me vat my father had and for Frederick ... because he is Prince of Vales now, he shall hav the £100,000 which I had.’

‘Frederick to have £100,000 But that is a nonsense.’ ‘It is a nonsense. For vat should he vant so much?’

‘Frederick to have £100,000 and you to have just the same as your father who had no big family.’

‘I tell him it is a nonsense ... and he say that he vill a difficulty have in getting the Parliament to agree to anything else.’

Momentarily Caroline thought of Frederick. He would have to come home now. The prospect filled her with some dismay. How strange! Once her dearest wish had been to have her little Fritzchen with her; but that was thirteen years ago. All those years she had not seen her son; he was Frederick now, no longer dear little Fritzchen. A German, she feared, who had never seen England; and she had her little William now and she desired for him the honours which would be Frederick’s.

He would have to come home now though because he was Prince of Wales. But certainly he should not have £100,000.

‘And Compton is a little slow,’ suggested Caroline tentatively, fearful that her husband might remember that the man was his choice.

But George was too angry to remember. ‘He does nothing ... nothing. He says: “The Parliament ... the Parliament ...” But I vill have them remember I am the King.’

‘Perhaps another man would be of more help to us. Let us think who there might be ... Pulteney

The King scowled and the Queen nodded to show she agreed with his lack of enthusiasm for that one.

‘And who else,’ she went on. ‘Wyndham ...’

‘No,’ said the King promptly.

‘There is Newcastle ...’

‘Newcastle.’ The King’s anger broke out. ‘That ugly baboon. Never! Never.’

The Queen nodded. They were remembering a long ago occasion when the King had forced Newcastle to become sponsor at one of the children’s christening, and the quarrel which had broken out between George and Newcastle at the bedside which had resulted in that bigger quarrel between the King and his son. George scowled now to remember the humiliation of being placed under arrest, while Caroline remembered how she had been parted from her children.

Newcastle was the last man. Yet he was an able statesman, and there were not so many of those.

‘It leaves only Valpole,’ said the Queen, and then feared she had been too bold.

‘Valpole ...’ grumbled the King.

‘He is perhaps the only man who can increase the Civil List . . . and it must be increased. Ve have so many children. Valpole can do it. I remember your father’s saying that this man could turn stones into gold.’

‘For his own benefit he vill do this.’

Tut to do it for us vill be to his benefit. The fat ox vill understand this.’

George was thoughtful. It was true.

‘It is no harm to send for him,’ said the Queen. ‘Then Your Majesty can judge him.’

‘I vill see him,’ said the King.

* * *

So Walpole presented himself to the Queen. Caroline was delighted that he should first come to her. George must not know this, but it was how it should be in the future, and it delighted her to know that Walpole understood this.

‘The King is not satisfied with the Civil List,’ she told him. ‘Compton does not seem to be able to make them understand how we are placed. He vill give me only £6o,000 a year and it is not enough.’

‘Your Majesty should have £100,000 a year,’ declared Walpole.

The Queen’s eyes gleamed. £40,000 more than Compton had wanted to provide.

‘You think this could be arranged?’

‘I believe, Your Majesty, that I could arrange it.’

A tacit agreement? wondered the Queen. Give me your support and you shall be well rewarded. £40,000 a year! It was a good sum.

‘You can svay the House, Sir Robert,’ she said with a smile. ‘I know that yell. Perhaps you have some suggestions for the King?’

‘The late King had a Civil List of £700,000, and His Majesty, then Prince of Wales, received £100,000.’

‘This Compton vants to give our son Frederick, now Prince of Vales, this although he is a young man unmarried and the King, when Prince of Vales, had a family to support.’

‘Your Majesty, the £100,000 which was paid to the Prince of Wales should be added to the £700,000 Civil List, arid Your Majesties should decide what you will allow the Prince from it.’

‘That is von good idea.’

‘Then I do not see why a further £130,000 should not be provided. The King’s subjects will rejoice to see him keep a more kingly Court than his father did.’

‘And the Parliament?’

Walpole smiled. ‘I think there is one man who can arrange their acceptance of these proposals.’

‘Sir Robert Valpole?’ asked the Queen.

Walpole bowed. ‘At the service of Your Majesties,’ he answered.

* * *

Walpole was triumphant. The King had implied that he should continue in his old office provided he get the Civil List passed through.

There was no subtlety about George.

‘I vant it for life,’ he said; ‘and remember, it is for your life too.’

It had not been difficult. The government knew that Walpole’s future hung on the passing of the Civil List; and it knew too that without Walpole it could not long exist. So there he was, the fat ox of a man, smiling blandly at them, laying the suggestions before them which he knew they could not afford to oppose.

Bribery of a sort—but not unknown in politics.

The King and Queen had their money; and Walpole was returned to power.

He laughed to himself as he rode down to Richmond to ell Maria about it.

‘You, my dear,’ he said triumphantly, ‘are not the only one who can’t do without me.’

While the King and Queen were congratulating themselves on the easy way in which they had acquired a large income a blow struck from an unexpected direction.

Letters were delivered to the King and among them was one from his distant cousin the Duke of Wolfenbüttel.

The Duke had written that he was in a somewhat delicate position, and he hoped the King of England would advise him what should be done.

King George I, His Majesty’s father, had left with him a copy of his will in case the original was lost in some way. He did not want to interfere in his cousin’s arrangements in any way, but he had heard that the King of Prussia had hoped that his wife, Queen Sophia Dorothea, who was after all the daughter of the late King, would have profited from her father’s will. The Duke of Wolfenbüttel was hard pressed at the time and he sent congratulations to his more affluent relative. He was also in a quandary, for on one side was the King of Prussia who, he believed, was ready to pay handsomely for a glimpse of the will, and on the other his friend and cousin George II. He was writing this letter first of all to ascertain the wishes of His Majesty. It gave him great pleasure to have the Duchess of Kendal as his guest at Wolfenbüttel, for he knew full well in what great regard the late King had held that lady....

When the King received this letter his eyes bulged with fury. He took it to the Queen who read it and looked very grave.

Who would have thought the sly old man would have made a copy and deposited it where it was out of the reach of his son’s hands!

And what a stroke of ill luck that the Duchess of Kendal, who would no doubt profit as much as anyone from the late King’s will, should at this time actually be staying as a guest in the house of the man who had a copy of the will.

The promptest action was clearly needed.

‘At least,’ she said, ‘Volfenbüttel has not made its contents known. I suppose Your Majesty will do as he is asking and buy this copy of the vill?’

‘Got damn him!’ cried George.

‘And as soon as possible. He might change his mind. The Duchess of Kendal is actually under his roof. Who knows what pressure she might bring to bear.’