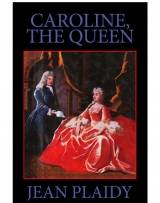

Текст книги "Caroline the Queen"

Автор книги: Виктория Холт

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Lord Hervey declined the chocolate they offered him. ‘It would be too rich for my digestion, Your Majesty.’ ‘Are you still living on nothing?’

‘I cling to my diet. It is the only way of keeping me on my feet.’

‘Oh, then you certainly must. What should we do if you failed to visit us.’

‘For Your Majesty’s sake I would live on husks for the rest of my life.’

‘Does he not say charming things, Caroline?’ asked the Queen.

‘I think Lord Hervey knows,’ said the Princess gravely, ‘that he is the most charming man in the world.’

‘The best heart in the world. The most charming man in the world. What a worldly pair you are! And how much travelled to be able to make such comparisons. I would content myself by saying of the Court ... of England ... but for you it must be the world.’

This pleasant raillery was interrupted by the arrival of the King.

He scowled to see the chocolate, but he was clearly too disturbed to give it the attention he would otherwise have done.

‘Anne is back in England,’ he said.

The Queen had grown pale and risen from her chair; the Princess Caroline gave a startled exclamation and Hervey, head bowed, was alert.

‘Yes,’ said the King, speaking rapidly in French. ‘She has come back. I have had notice of this.’

‘But why ...?’ asked the Queen.

‘She had taken off and the sea was rough, so she says, and she feared for her life and that of the child, so she ordered the captain to return to England. She is at Harwich now … abed. And says she cannot stir for fear of a miscarriage.’

‘We must have her brought here ... or we must go to her,’ began the Queen; but the King interrupted angrily: ‘She talked of lying-in in England. It is what she wishes. Orange wishes her to go to Holland, of course.’

‘It is only natural that he should wish the Prince of Orange to be born in Orange, Your Majesty,’ said Hervey.

The King looked at Hervey and grunted. Then he nodded. ‘Natural,’ he said. ‘Natural, of course. She’ll have to go back.’

‘But if she is ill ...’ began the Queen; the King silenced her with a scowl.

‘She can’t lie-in here,’ said the King. ‘It wouldn’t be right and ... think of the expense! We have had enough with her marriage. She shall rest awhile and then . . . back to Holland for the birth of the baby.’

A great deal of correspondence was going on between Harwich and London.

The Princess Anne remained in her bed at Harwich and wrote to her parents that she must stay in England. She must lie-in there. It was imperative for her own safety and that of her child.

The Queen was distraught and the King growing more and more angry every day; but the Princess of Orange was using all her powers of persuasion to remain while the Prince of Orange, realizing that as a matter of honour his son should not be born in England, insisted that his wife return to Calais where he would meet her and take good care that she suffered no ill effects from the journey.

‘She must go without delay,’ said the King.

The Queen wanted to remonstrate with him but dared not. Lady Deloraine was his mistress and she was not a very important woman, but Walpole had pointed out that although she was a silly, empty-headed creature, fools were often very easy to handle by scheming men, and the fact that the King had now a more or less settled mistress would make them watchful. The Queen must not lose her hold on the King.

Therefore what could the Queen do but side with her husband, particularly as she knew from reports that Anne’s malady was largely due to a desire to stay in England, and not go back to Holland.

Poor Anne! She had her husband and her title; and soon she would have her child; that was all she needed. She did not want to have to go to a strange land and live with a monster when there were her own dear family in England. Not that Anne had ever held her family very dear. But, reasoned the Queen, familiarity was always dear, particularly when it was about to be lost.

If only Anne could have stayed for the confinement she would have been happy.

‘She must go,’ thundered the King. ‘Her place is with her husband.’

The people took sides and of course were on Anne’s. She wanted to stay in England naturally enough, said the English. She did not want to go back to that deformed husband of hers. Well, who could blame her?

The lampoonists had a new theme.

‘Got dam the boets,’ said George, and took action. The Princess Anne was to return to Holland, but she was not to come to London. He was not going to have the people lining the streets and cheering her. She was to take the nearest route from Harwich to Dover.

A letter came back from the Princess with the plaintive comments that her advisers had told her that the roads between Harwich and Dover were impassable by coach at this time of the year and that if she went to Dover the only route would be by way of London.

The King was furious, but was assured by his advisers that what the Princess said was true and if she was to go to Dover she must come by way of London.

‘Well then,’ said the King, ‘she may come and go over the bridge, but she shall not lie-in in St James’s, nor shall she stay in London but just pass through.’

‘Does Your Majesty mean,’ asked the Queen, ‘that none of us are to see her?’

It is what I mean, Madam,’ he said, growing irascible. It seems ... hard....’

‘You are criticizing my conduct of this affair?’

‘Of course not.’

‘I am glad of that,’ he cried, ‘for I would have you know, Madam, that you would do better to stuff your chocolate and grow as fat as a pig though I own this is bad for you ... than interfere with what I decide shall be done.’

His face purple he strode from the apartment and the Queen, her face tinged with pink, her downcast eyes filled with tears, was silent.

And so the Princess of Orange passed over London Bridge and through London without seeing any of her family, and as the journey had been kept a secret there was none to cheer her as she passed along. At Dover she embarked in the vessel which was waiting to carry her to Calais; and there Pepin was waiting for her, looking even more hideous than she remembered him because of the sourness of his expression.

They made a somewhat sullen journey through Flanders to Holland.

* * *

In his lodgings in St James’s Lord Hervey was waiting for the arrival of his mistress.

He had not yet tired of her for she was amusing and of course her greatest charm in his eyes was her relationship to the Prince of Wales. He needed such a fillip to rouse his desire for a woman.

For I do believe, he said, studying his reflection in the mirror in his bedchamber, I have a greater preference for members of my own sex. Dear Stephen!

They were still the best of friends, but since his deeper friendship with the Queen, his platonic but extremely enjoyable flirtation with the Princess Caroline, and his intrigue with Anne Vane, he had little time for further outlets. Stephen must understand this.

Oh dear, he thought, it is a very feminine entourage at the moment!

He was looking pale. He pulled down his lids and looked at his eyes. Not as clear as they might be! Was he taking too much rich food? His figure was as elegant as ever. He would hate to be like le gros homme. What a figure! And the man’s legs were very swollen. Weighed down with all that weight doubtless. But he had his love affairs. The one with the Skerrett woman was quite notorious.

Well, each to his taste, and now my little Vane you are overdue and I long to hear the latest exploits of His Royal Highness.

He had taken to receiving her here in his own apartments because he did not care for her house when all the servants were away—and of course they must be away for her to receive him there.

A man needed a little refreshment after the exertions of love-making. A dish of tea, a little fruit, neither very harmful for the figure and so reviving!

He smiled to think of Anne opening the door of her house for him and ushering him in. What risks they ran—at least she did. If this liaison were discovered he would merely be laughed at and perhaps admired in some quarters. He could not be more disliked by the Prince of Wales than he was at present. But she, poor girl, would be ruined. If Frederick discarded her what could she hope for? Some other man perhaps to set her up? But no one, of course, could give her the standing which the Prince of Wales could. Yes, she faced ruin for the sake of receiving him. A pleasant thought, for it was gratifying to have such devoted friends.

His wife, Molly, was away on the Continent with some friends and she would be there for some months. Well, if she knew that he were entertaining the little Vane she would only shrug her shoulders and laugh. She had never expected fidelity from him. She was faithful, but not out of love for her husband; simply because love-making—marital or extra-marital—had no charm for her.

He couldn’t have made a more successful marriage.

And here was his mistress, be-cloaked and be-hatted, to hide herself so that no one would see the Prince’s mistress entering the lodgings of that scandalous fellow, Lord Hervey.

‘My dear Anne! ‘

‘My dear lord, I thought I should never get here.’ ‘Don’t tell me His Royal Highness made difficulties?’

‘He stayed longer than I believed he would, and so delayed me.’

‘He is coming back tonight?’

‘No. I have the evening free.’

‘Then let us make the most of the time at our disposal. I have had a little supper prepared before I dismissed my servants.’

‘Supper for two?’ she asked. ‘I hope so, for although you eat like a bird, I eat like an ox.’

‘I prefer the lion and the lamb because they lie down together.’

Anne laughed and said she hoped he didn’t say such things to the Queen ... or the Princess Caroline.

‘You would be surprised if you heard what I said to them.’

‘Everyone is surprised.’

They sat down at the table and he told her that his wife would not be back for several months and as there was no danger of her coming here he did not see why they should not make his lodgings their meeting place.

‘It’s comfortable ... as far as I can see,’ she said. ‘Well, let us sup.’

‘I’m ready.’

Over supper they talked of the latest development in the estrangement between the Prince and Bubb Dodington.

‘Of course, when he bought Carlton House with money borrowed from Bubb he told his dear friend that he wanted it because it was next to his house in Pall Mall and he gave Bubb a key to the door in the wall which separated their gardens. “Call any time you like, dear Bubb. Don’t stand on ceremony in the house you have bought! “ For bought it he had. Bubb will never see his money, you can be sure. In fact Fred boasts of it and laughs every time he comes into the house. But those days are over. No more free and easy for Mr Bubb! Do you know what Fred has done?’

‘I can’t wait to hear.’

‘He’s had the door bricked up. Not secretly. He had more workmen than he needed hammering away there. He didn’t want anyone to have any doubt what it was all about. Poor Mrs Behan . . . really Mrs Bubb, you know.’

‘Interesting situation,’ commented Hervey. ‘The wife parading as the mistress. Now the other way round ...’

‘Oh, there’s some other woman in it who’d get money from him if she knew he was married to someone else.’

‘So he is a romantic after all, our poor Bubb. And two women love him! ‘

‘Love his money you mean.’

‘Well, they are only following the royal example. But the Prince is not even faithful to poor Bubb’s money!’

‘Bubb has Mrs B. She’ll look after him. He’ll never face Court after this. I think she’ll make him retire to the country.’

‘The best place for him. There is a great deal to be said for the country.’

‘There are some who think that’ll soon be my lot.’

‘What’s this?’ There was real alarm in Hervey’s voice.

‘Several of my friends are pointing out to me that Fred is seen very often in the company of Lady Archibald Hamilton.’

‘That woman! She’s all of five and thirty. She’s been married for years! Imagine it! Years of lying beside a man old enough to be her father! ‘

‘But not too old to give her ten children ‘

‘And you are afraid of a mother of ten—five and thirty years old at that! ‘

‘It’s not I who am afraid. It’s my friends who are afraid for me.’

‘Hamilton,’ mused Hervey. ‘He’s so quiet I can hardly remember what he looks like. He’s a Lord of the Admiralty, I believe.’

‘That’s so. Lord Archibald Hamilton, Scottish and complacent.’

‘Would he be complaisant too?’

‘No one ever seems to have seen him put out.’

‘A born cuckold. Beware. Some men choose their mistresses for their husbands.’

‘Not my Fred. He’d never be wise enough.’

So they chatted over the meal, and when they had finished, retired to the bedroom.

They made love and as they lay talking Anne suddenly cried out in pain.

Hervey sat up in alarm. ‘What ails you?’

‘The colic,’ she said. ‘I’ve been having it more frequently lately. I’ll be all right in a moment.’

‘Lie still,’ he said, and she lay back and closed her eyes.

She looked very ill and was suddenly seized with convulsions. Hervey remembered what she had told him of these fits to which she was subject, but he had never seen her in one before. She had once said that a physician had told her that she could die during one of her fits.

‘Anne,’ cried Hervey, ‘for God’s sake ... tell me what I can get you?’

She did not answer and he stood by the bed in dismay, looking down at her writhing body.

She is going to die, he thought. Here in my bed she is going to die. What can I do? The Prince’s mistress found dead in my bed! This will be the end of everything. Even the Queen and the Princess Caroline could not get me out of this trouble.

‘Anne! ‘ he cried frantically. ‘Anne.’

But she did not hear him. Fortunately a hypochondriac such as he was had plenty of pills and cordials to hand; and as the collecting of medicine was a hobby of his, and the discussion of varied diseases one he found extremely fascinating, he was not at so much of a loss as most men would have been in the circumstances.

He hurried to his medicine chest and brought out gold powder which he forced down her throat. But she continued in convulsions. He then took a bottle of cordial and gave her some of that, without effect.

She was moaning softly and he was growing more and more terrified every moment.

He went back to his medicine. What can save her? he asked himself frantically. And was it wise after having given her the gold powder and the cordials, to give her more?

‘Tell me what I can do?’ he cried. ‘Tell me what you want?’

Her writhing ceased and she was suddenly very still.

In terror he took her wrist. Her pulse was feeble but he could feel it. Thank God she was still alive!

He called her name again and again, but she was in a deep faint.

What could he do? He daren’t call a doctor who might recognize her. It was so widely known that she was the Prince’s mistress. The story would be all over the town by morning.

He bent over her. ‘Anne,’ he cried urgently. ‘You must rouse yourself. I must get you out of here.’

But still she did not answer.

He sat on the bed watching her. He saw the pleasant position he had made for himself at Court lost for ever. What would the Queen say when she heard? It was not that she would be shocked, but how could she keep close to her a man who had been involved in such a scandal?

‘Anne!’ His voice rose on a note of shrill joy, for she had opened her eyes. ‘Oh, Anne ... thank God you’re alive.’

‘I ... feel so weak,’ she said.

‘I know ... I know ... but we must get you out of here.’

‘Get a hot napkin and put it on my stomach. I’m shivering.’

It was true. He could hear her teeth chattering.

He hurried away and found napkins which he warmed; he brought them to her but she started to twitch again and he called out in his agony of fear.

‘What do you need?’ he cried. ‘What can I get?’ Have you gold powder?’

He brought it and she swallowed it.

‘That’s ... a little better,’ she said.

‘You must get up. You must get dressed. We must somehow get you back to your house.’

But she shook her head and closed her eyes.

‘Come, Anne,’ he said. ‘You must try to rouse yourself. You must not be found here. It will be the end of you ... the end of us both ... if you are.’

But she did not seem to take in what he said.

He managed to lift her out of the bed; he sat her in a chair and began to dress her. She was limp and unable to help him, but after a great deal of fumbling he had her dressed. She swayed as he made her stand, but he was feeling better now. He managed to get her out of the house and half carry her some little distance away.

Good luck was with him, for he found a Sedan and setting her in it paid the chairmen handsomely to take her back to her house.

‘The lady had been taken ill,’ he said.

The chairmen replied that they would see that she arrived safely.

Hervey went back to his bedroom, threw himself on the bed, and discovered that he himself was on the verge of collapse.

* * *

The King’s birthday, the 10th November, must be celebrated at St James’s and a round of festivities began.

Caroline, whose health had been growing steadily worse over the last months, felt the strain badly, yet she dared not complain to the King.

Hervey was constantly at her side. He had quickly recovered from the shock of what had happened in his apartments when he saw Anne Vane going about her everyday concerns as though nothing had happened. They never spoke to each other publicly, keeping up the pretence that they were enemies all of which added to the piquancy of their affair. She came again to his lodgings and told him that she had had such attacks before—colics, she called them. She recovered, and after a day’s rest was perfectly well.

From then on the fear that she might die in his bed was an added fillip to his feelings for her and they went on meeting as frequently as ever.

In spite of his cynical attitude to the world, Hervey had a certain feeling for the Queen; and when he saw her looking so ill he ventured to remonstrate with her while he asked himself whether he was really concerned for her health or the effect her illness or death might have on his fortunes. His great virtue, he assured himself, was his determination to be frank with himself.

‘These birthday celebrations fatigue you greatly, Madam,’ he told her.

‘They will soon be over.’

‘Should you not explain to His Majesty that you need to rest?’

‘My lord, what are you thinking of? You know His Majesty’s attitude to illness. He hates it, and there are some things which he hates so much that the only way he can tolerate them is by pretending they don’t exist.’

‘That, Madam, is a state of mind which cannot exist permanently.’

‘You love your illnesses, my lord.’

‘I respect them. That is why I am constantly at your side instead of languishing in my bed.’

‘I have been twice blooded recently.’

‘All the more reason why you should rest, Madam.’

‘Pray don’t scold. I have known the King when he has been ill, get up from his bed, dress for a levee, conduct it, and when it is over return to bed, hiding from all but his most intimate servants the fact that he was ill.’

‘It is not Your Majesty’s custom to follow His Majesty’s follies.’

‘Hush, you young idiot.’

‘A most devoted, and at this moment, anxious idiot, Madam.’

‘Oh, come, come. You indulge me! ‘

‘Would I might do that.’

You please me enough with your tongue, my lord.’

Then I will make further use of my privilege and say that no member of your family, Madam, will ever admit to being ill ... nor acknowledge illness in others.’

‘If that is all our subjects will have to complain of us we shall be fortunate.’

‘I complain now, Madam, most bitterly.’

‘But you, my child, love illness, you pamper it, you study it, you revel in it. We merely spurn it and drive it away.’

‘We shall see, Madam, whose method is wiser.’

‘I hope not, my lord. I hope not for a long time.’

* * *

Sir Robert Walpole, himself suffering from the flying gout, was loath to attend any of the birthday celebrations; he was longing for the quiet of Norfolk where Maria and their daughter would be with him.

Twice a year he holidayed there and he was beginning to think that those two holidays were the best times of his year. Why did he go on fighting a cruel Opposition, a foolish King, and a Queen whom he respected but of late had seemed to be against him?

He allotted himself twenty days in November—twenty days of peace with Maria in his cherished Houghton among his treasures. All his treasures, he told himself with a rare sentimentality.

He looked back on a hard time. It had been particularly difficult keeping England out of war and the elections had not gone very well for him. He was still in power but with a reduced majority.

He must, he supposed, put in an appearance at the King’s celebrations otherwise there would be complaints against le gros homme. One had to placate the little man all the time.

He dressed with reluctance and presented himself at the Queen’s drawing room.

As he made his way to her side he was shocked by her appearance.

She’s a sick woman, he thought. Why does she not admit it? Doesn’t little George see. Of course not! When did he ever see what he didn’t want to?

‘Madam,’ he said, as he kissed her hand, ‘I have come to pay my respects and to tell you I shall shortly be leaving for Houghton.’

‘My poor Sir Robert, you are in need of a holiday.’ She swayed a little.

‘Madam ... you are not well.’

‘I was blooded twice recently. It takes a little time to recover.’

She is going to faint, he thought.

He caught Lord Hervey’s eye and he knew that Hervey understood. ‘Your Majesty should be resting,’ said Walpole. ‘Perhaps Lord Hervey would ask His Majesty if he would retire so that the Queen can go to her bed and rest a while.’

The Queen was about to protest, but Hervey did not wait. He went to the King and surprisingly George must, too, have been aware of his wife’s wan looks for he made no protests, but for once ignoring sacred time he retired to his apartments, leaving the Queen free to do the same.

* * *

In the Queen’s closet, Sir Robert paced up and down, talking gravely.

‘Madam,’ he said, ‘your life is of such consequence to your husband, your children, and to your country that to neglect it is the greatest immorality you can be capable of.’

‘Sir Robert, my dear friend, you flatter me.’

‘It is no flattery, Madam. I would be frank. This country is in your hands. The King’s fondness for you and the regard he has for your judgment are the only reins by which it is possible to restrain the natural violences of his temper or to guide him to where we wish him to go. We know that he does not care for the company of men, but cares greatly for that of women.’

‘You think he may have a mistress who will seek to influence him?’

‘That is possible. She might govern him. But I was thinking that if you do not take care of your health you may not be with us and he might marry again. What then? What if the Prince were inflamed against his father more than he is already? Oh, I see a thousand dangers which would come to this realm if you were not in the position you now hold.’

The Queen smiled sadly. ‘Your partiality to me, Sir Robert, makes you see many more advantages in having me, and apprehend many greater dangers from losing me, than are indeed the effects of the one or would be the consequences of the other.’

‘But you agree there are dangers?’

‘The King would marry again if I died, I am sure. Indeed I have advised him to do so. As for his government, he has such an opinion of your abilities that were I removed everything would go on as it does now. You have saved us from many errors, and this very year have forced us into safety whether we would or no, against our opinion and against our inclination. I own this. The King sees it; and you have gained his favour by your obstinate but wise contradiction, more than any minister could have done by the most servile compliance.’

Sir Robert kissed her hand for he believed it was noble of her to confess her fault; but it was what he would have expected of a woman of her intelligence.

‘I need you, Madam,’ he said. ‘I believe that without your help I should not be able to persuade the King into any measure he did not like. So, therefore, I beg of you take care of your health. I think I will not go to Houghton.’

‘But why not, my dear Sir Robert! You need to guard your health even as I do.’

‘I am so concerned for you.’

‘But this is nonsense. Go you shall. I order you.’

‘Then if you will allow Lord Hervey to send me accounts of your health ...’

‘I shall command him to do so.’

‘In that case, Madam. I take my leave.’

When he had gone, Caroline lay on her bed, and there were tears in her eyes when she reflected on the friendship of her dear gros homme.

When Walpole left the Queen, he went straight to Hervey’s lodgings to tell him of the interview and how he wished him to keep a watch on the Queen’s health.

This Hervey said he would do; and he added his fears to Walpole’s.

Then Walpole as was his custom proceeded to tell Hervey all that had been said.

Hervey suddenly clapped his hand to his mouth and said: ‘A fearful thought has struck me. The King may have heard every word you said! ‘

Walpole grew pale. ‘This will be the end for us both! ‘ he declared.

‘I may be wrong,’ said Hervey. ‘But I must tell you that I went to look for the Princess Caroline shortly after you joined the Queen. You know she always leaves her mother when you arrive to talk of state affairs.’

Walpole nodded.

‘One of her pages told me that she had left her mother when you went in and joined her father who was with the Princesses Amelia, Mary, and Louisa. He went through into the Queen’s bedroom with them; and you know that is the room next to the Queen’s closet in which you were talking to the Queen.’

‘He could have heard every word! ‘

‘If he listened.’

‘Certainly he would listen. I remember once how he deliberately hid himself in a closet and left the door open so that he could hear what passed between myself and the Queen.’

‘Then ...’

‘I can only repeat. This will be the end for us both.’

‘He will have been forced to see himself as you and the Queen see him—not the all-important king from whom all wisdom flows. This is disaster.’

‘You must find out if it is true. Can you?’

‘I am sure I can.’

‘Then for God’s sake do and let me know before I leave for Norfolk. If he has heard what we said then I may as well stay there. As for the Queen ...’

‘Leave it to me. I will discover.’

So a very discomfited Walpole left; and it was not a bad thing, reflected Lord Hervey, for all men to see how easily, when they are at the height of power, they can fall to ruin.

Walpole would be feeling now as he had when he had thought Anne Vane was going to die in his bed.

He was almost certain that the King had not overheard, for he had a shrewd idea where he would have gone after he had a few words with his daughters.

Still it was good to know that the great Walpole regarded him as such an invaluable friend; it was very gratifying to have him waiting eagerly for the note which would reach him early next morning.

He went to the page to whom he had spoken before and asked where the King had gone when the Princess Caroline had joined him and her sisters.

The page smiled.

‘He went to the nurseries, my lord.’

‘I’ll swear he spent a long time discussing his children’s education with Lady Deloraine,’ said Hervey lightly.

At which the page gave a veiled snigger.

Scandal quickly went the rounds, thought Hervey.

He then went direct to Walpole’s house in Chelsea because it was always so much more pleasant to deliver welcome news in person and Walpole would remember how his good friend did not wait until the morning.

He was greeted eagerly.

‘All is well! ‘ cried Hervey. ‘He was not in the Queen’s closet, and instead of hearing your truths he was talking love and devotion with his daughters’ governess.’

They laughed together, like old friends. The bond between them was stronger than ever.

* * *

And when Hervey was next with the Queen she spoke to him of her anxieties over Walpole.

‘He seemed to me so anxious. He is worried about his position, I believe. These last elections shook him. I feel that some of the spirit has gone out of him.’

Lord Hervey loved to enlighten people, particularly those in positions of power such as the Queen or Walpole, so he whispered confidentially that Walpole’s troubles were more personal than political.

‘Oh?’ said the Queen. ‘Does this in any way concern that woman he so dotes on?’

‘She is ill, Madam. And could be dangerously so. This is one of the reasons why Sir Robert is so distrait at this time.’

‘Poor Sir Robert! But I am surprised that a man of his talents should feel so deeply towards such a woman.’

‘Your Majesty has heard gossip of this woman?’

‘Well, I heard that he paid so much for her and that she makes demands upon him.’

‘I have heard that he paid £6,000 “entrance money”! ‘

‘You are an enfant terrible, my child.’

‘Would Your Majesty care to terminate this rather shocking conversation?’

‘I have lived too long at Court to be easily shocked by the morals of those about me. Pray go on.’

‘Maria Skerrett lodged with her stepmother next door to Lady Mary Wortley Montague, and that’s how Walpole met her. He was immediately attracted, but then before he met her he was flitting from woman to woman like a gay old ram in a field of sheep.’

The Queen laughed.

‘And, so the story goes, the transaction was made and a year later young Maria was born. Then our minister acquired the Old Richmond Lodge and made a home of it for them all. And every week-end, there he went to enjoy the sweets of domesticity. He was a changed man since he met Maria.’

‘I am glad he has amusement for his leisure hours. She must be very clever to have made him believe she cares for him.’

‘What, Madam, she does.’

What, that man with his gross body, that enormous stomach, and his swollen legs! ‘

Poor Caroline! thought Hervey. She is envious of this devotion between her minister and his mistress. She is beginning to find the strain of placating George unbearable. ‘Well, I hope she is soon better and that care is lifted from his shoulders,’ said Caroline briskly.