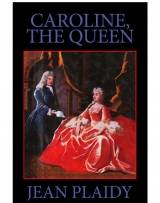

Текст книги "Caroline the Queen"

Автор книги: Виктория Холт

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Regency

THE Queen was busily reading letters from Hanover. The King and Townshend, who was with him, must be kept in touch with foreign affairs, although domestic matters were left to Caroline and her Council. Townshend was growing jealous of Walpole’s alliance with the Queen; the two men were brothers-in-law for Townshend had married Walpole’s sister Dorothy who had been devoted to her brother and to her husband; she it was who had been in fact responsible for the great accord between the two men and had brought them to a partnership which had been profitable to them both. But with the death of Dorothy, which had brought a great grief to both men, the alliance had weakened. Townshend, a man of almost puritanical views, began to look with distaste on the life Walpole led: drinking with his friends down at Houghton, his coarse conversation, and living openly with Maria Skerrett while his wife was alive. Moreover, they were thinking along different lines politically.

Walpole had been glad to have Townshend out of the country, but there was a disadvantage to that, for being in close company with the King he might attempt to influence him; and without Caroline there to guide George, this could have disturbing results.

Caroline as usual was in complete accord with Walpole and agreed that Townshend must be carefully watched as it would not be difficult for him to drive a wedge between herself and the King.

George was writing long letters to her from Hanover. He was a good letter writer and in fact more fluent with the pen than verbally. It was true he wrote either in French or German which he spoke and wrote easily.

All was going well in Hanover. He had one regret which was that his dear Caroline was not with him. He wanted her to know that there would never be another woman who meant so much to him as his dear wife, and he often thought of the day when he had come courting her and fallen in love on sight—a state which had never changed with him.

He would not say that lie had not a mistress. The German women were different from the English. They were more docile. He had come to the conclusion that he was more honoured as an Elector than as a King. In England there was always the Parliament; in Hanover there was only the Elector. The English did not deserve to have a King. They wanted to govern themselves. So they set up a Parliament. He was heartily sick of parliaments. Here in Hanover he had his Council meetings, yes; he had his ministers; but he was the Elector and he would have his dear Caroline know that the Elector in Hanover was a far more respected person than the King of England.

Caroline paused for the letter was long; and she was thinking that the rhymes of the lampooners still rankled. In Hanover none would dare mock the Elector. It was a pity they had in England.

He went on to describe his latest mistress and all the intimate details of his love affair. How she wished he would have the tact to keep that to himself.

He was a man of great needs, as she knew. He must like most men have his mistresses, and now that he was a bachelor for a time that was necessary. She would understand that, for was there not complete understanding between his dear Caroline and himself? He had found a warm-blooded creature—’Plenty of flesh on her, my dear Caroline—you know our German woman—and she is so delighted to be noticed by the Elector. She trembles with joy every time I approach.’

Caroline sighed. This was too much. Let him at least keep the details to himself. She read on wondering what other revelations were to come.

The next communication was more startling. ‘Townshend thought we had given you too much power and wanted to curtail it. He was working out some scheme whereby the smallest matters should be sent for our approval before you could put them into action. I pointed out to him that I trusted my dear wife as I trusted no other. I told him he did not know how I had always taken you into my confidence, how I had kept you informed of all state matters and even discussed them with you. “No,” I said to Townshend, “if there is one person in England whom we can safely trust that is the Queen.”‘

There was no doubt that Townshend must be watched.

* * *

Walpole was a constant visitor, and when she disclosed the information that Townshend had tried to curtail her power, he became very thoughtful.

‘I think,’ was his comment, ‘that something must be done about my brother-in-law. He is becoming a nuisance.’ ‘You would have to be very careful.’

‘Your Majesty should have no fear.’

‘I am sure I can leave him in your capable hands.’

‘We must see what can be done when he returns from Hanover. In the meantime there is the Treaty of Seville with which to concern ourselves. And one matter of less importance, but one which we cannot ignore: This affair with the Portuguese government.’

Caroline nodded. She had been disturbed when she had heard that the Portuguese had put an embargo on a British ship which was lying in the Tagus. The whole world must know that Britain would not allow her ships in foreign ports to be so treated.

‘Let us deal with this matter immediately,’ she said. ‘Then we can give our attention to the Spanish Treaty.’

‘Your Majesty is right as usual. If we show ourselves firm with the Portuguese that will be to our credit in the other matter. We must take a firm line.’

‘Firm,’ agreed the Queen, ‘but friendly. I will send for the Portuguese envoy and together we will put the matter before him.’

* * *

The Queen’s handling of the Portuguese incident was effective. The Portuguese agreed to raise the embargo without delay and Townshend wrote that the King liked extremely what Her Majesty said to the Portuguese envoy.

Caroline was delighted, but she knew that the Spanish treaty was a far more delicate matter.

This treaty was calculated to end the conflict between Spain and England which had long had an adverse effect on English trade with America. Peace between the two countries would be an excellent prospect and desired by both sides, but there was one point in the treaty which required very careful handling. This concerned the Rock of Gibraltar. The English had captured this in 1704 and it was a matter of some dismay to Spaniards that the English should own this little portion of the Spanish mainland. However, it was a very important spot and Caroline and Walpole were most eager not to relinquish it.

It might, Walpole pointed out to her, be the one clause in the treaty which would cause the Spaniards to hesitate.

‘Townshend,’ he said, ‘is advising we give it up for the sake of the other concessions we shall receive.’

‘And your advice?’

He smiled: ‘I imagine that Your Majesty and I are in accord on this matter. I would say that we should do our utmost to retain it.’

‘Unless of course

Walpole nodded slowly.

‘You have raised it with the Spaniards?’ asked the Queen.

‘No.’

They smiled. ‘Then we will say nothing ... we will pretend the thought of Gibraltar has never entered our heads. It is just possible that we may conclude this treaty without its being mentioned.’

‘The Spaniards are most eager to conclude it.’

‘And so are we, but we will hide the fact.’

They were as usual in complete accord.

* * *

The Queen decided that all her family should accompany her to the house of Sir Robert Walpole in Chelsea to dine with her favourite minister.

It was the greatest honour in the world, Walpole had told her; and he had made all the arrangements himself.

These were pleasant days. If only George would stay in Hanover, if only the Queen reigned alone, how much simpler state affairs could be!

Between them—he and the Queen—they had successfully concluded the Treaty of Seville. William Stanhope, England’s Ambassador and Plenipotentiary in Madrid, had worked in close co-operation with Walpole and the Queen and as a result the Treaty had been completed without the loss of Gibraltar. In fact—as Walpole and the Queen had hoped—it was not mentioned by the Spaniards. This Caroline and Walpole regarded as their triumph and it was when this matter had been successfully concluded that the invitation to dine at Chelsea had been humbly tendered and graciously accepted.

Princess Anne was a little shocked. ‘Why,’ she said to Amelia and young Caroline, ‘our mother seems to forget that we are royal princesses. To dine at Chelsea ... in the home of Robert Walpole ... a commoner!’

‘Our mother thinks more highly of this commoner than she does of some princes,’ pointed out Amelia.

‘Oh Fred! Well, who would think anything of him?

I wish he would go back to Germany where he belongs.’

‘He belongs there no more than the rest of us.’

‘Amelia, you’re a fool!’

Caroline moved away as she always did when her sisters quarrelled. It was so disturbing; and in fact she found nothing to dislike in Frederick. She was sure that if they had been affable to him he would have been very ready to be so with them. But she never attempted to argue with her sisters.

Nov they were all assembled for the journey to Chelsea. The whole Court knew they were going and it was slyly said that if the King decided to stay in Hanover the Queen might invite Sir Robert Walpole to live permanently at the Palace. Why not—he ruled England—he and the Queen together.

Frederick said little, but he was less contented than he had been. Several of his friends had pointed out that they had never heard of a Prince of Wales being passed over for the sake of his mother. If his father died tomorrow he would be King, but he wasn’t considered worthy to be Regent in his absence!

It was a little strange, thought Frederick. And although he would have hated to be closeted for hours with that crude creature Walpole, poring over dull state papers, he was beginning to believe that he should have been offered the Regency.

It was rather pleasant to have a grievance. People were so sorry for him; they seemed to like him better for it. Moreover, his mother and father showed rather obviously that they didn’t greatly care for him, so why shouldn’t he gain a little popularity at their expense?

He glanced at his sister Anne who immediately scowled. Amelia was indifferent. Caroline might have been more pleasant but he thought her a dull little creature; as for his brother William he wanted to box his ears every time he saw him; and the little girls were nonentities.

He was not really very satisfied with his family.

When they reached Chelsea, Walpole was waiting to greet them.

He behaved as though this was the greatest honour that could befall him, but all his deference was directed towards the Queen; the rest of them were greeted very perfunctorily.

He had invited many guests for this glorious occasion, but the royal family were to dine in a room alone.

This pleased Anne who remarked to Amelia that it was no more than was right. Frederick was less pleased; he could think of much brighter company than that supplied by his own family; in fact he could think of few more dull.

The Queen however was delighted, for Sir Robert himself waited on them. He said it was not only the greatest of honours but the greatest of pleasures.

‘What a respecter of ceremony you are, Sir Robert! ‘ said the Queen with a laugh. ‘I had not expected to stand on such ceremony here in your home.’

‘Madam,’ he said, ‘no matter where, the Queen’s royalty must be maintained.’

How he delighted to serve her; and she delighted to be served!

Afterwards the candles were lighted and there was dancing. The Queen was pleased to look on. It was so comforting to rest her legs. None of the Princesses danced at first. Anne declined for them all for she considered it beneath their dignity; but the Queen implored Sir Robert to dance as she liked to watch the quadrille.

Frederick joined in and Anne scowled at him. How like him to curry favour! Everyone would now be saying that the Prince was more affable than his sisters.

The Queen was smiling and very gay. ‘Dancing becomes Sir Robert,’ she said. ‘How easily he moves! I should not have believed it possible. Ah, and there is Lord Hervey. Lord Hervey,’ she called, and he came and bowed to her.

‘I see you are not dancing, my lord.’ She turned to her daughters. ‘Now there is an excellent dancer. My lord, you should join the dancers.’

‘With Your Majesty’s permission it would give me greater pleasure to remain at your side.’

The Queen looked well pleased. Anne thought: This young man, who can at times look more like a woman than a man, is almost as great a favourite with her as Walpole himself.

‘I shall not give you permission,’ said the Queen. ‘Perhaps one of the Princesses will dance with you.’

Anne turned haughtily away. Amelia had caught sight of the Duke of Grafton. But Caroline had half risen. So Lord Hervey could do no more than beg for the honour.

The Queen sat back in her chair. Such a pleasant day! She was still glowing with pleasure over the successful conclusion of the Spanish Treaty.

Fleetingly she thought of George in Hanover. She had a picture of him caressing some plump beauty, and hoped her charms would be enchanting enough to keep him there a little longer.

A strange thought for a wife to have of her husband, she reminded herself; and then laughed for why should she practise self deception? No good ever came of that.

* * *

Meanwhile George was very happy in Hanover. Here he was supreme ruler; and after all this was his native land. He was more of a German than an Englishman—a fact which because the case had been the same with his father he had preferred to forget. But now his father was dead and he could be himself.

Herrenhausen! Home of a hundred delights, with its glorious gardens, its linden avenue, its hornbeam hedges, its lawns and fountains. Here he instituted the same rules as he insisted on in England, but no one laughed at him here. The Germans were so much more serious than the English. One could not imagine them sitting in taverns composing so-called witty verses. No one would laugh if they did. No sly remarks, no disturbing lampoons; only deep respect for their Elector and eagerness to show their pleasure on his return.

Hanover was delightful.

The English in his retinue were a little restive, but much he cared for that! Let them be. They did not like a life that was governed by the clock. They did not appreciate the importance of time.

Another thing, here he spoke German and there could be no tittering about some quaint turn of phrase or the inability to pronounce certain words. It was he who would have the laugh of the English here, if he could be amused by such a triviality, which he could not. It was the English who were always finding something to laugh at and in particular the opportunity to ridicule others.

He never wanted to leave Hanover.

He had two mistresses, because one, in his opinion, was not enough for his prestige, and they were plump, flaxen-haired German women, docile, honoured to be selected, and with a proper understanding of their position in life. He was contented.

Every morning at precisely eleven thirty he would stand waiting for the arrival of those of his retinue who were lodged at the Leine Schloss. His watch in hand he would smile when they arrived exactly on the minute.

They would return to the Leine Schloss later in the day and the process would be repeated at six o’clock. After that there would be the banquet, at which sausages and sauerkraut dominated, to the disgust of the English, and this was followed by cards. But the King would rise at exactly the same minute each night no matter whether the game was finished or not.

Because he had grown very interested in the theatre during his life in England, plays were performed twice a week at Herrenhausen. The performance began at the time decided on by the King and must end exactly on the minute—otherwise he would rise and leave and the show would therefore end in any case.

The English sneered and grumbled among themselves. It was like living in a monastery, they said. They wondered he didn’t set up a system of bells. But there was one advantage; everyone in the Court would know exactly where the King was at a certain time.

But these habits which had caused such mirth in England were placidly accepted in Germany.

The days were however enlivened by the controversy with the King of Prussia, who was not only his cousin but his brother-in-law. George had hated Frederick William when they were boys and he had seen no reason to change his mind. As for Frederick William, he liked nothing better than trouble, so he plunged into the argument with all the violence of his nature.

Townshend tried to persuade the King not to take Frederick William’s insults too seriously.

‘We know, Your Majesty, the nature of the King of Prussia. The stories we hear of the way in which he treats his family are so shocking that they are almost incredible.’

‘Nothing is incredible with that man. He may browbeat his family but he must remember that I am the King of England.’

‘We shall not allow him to forget that, Your Majesty.’

‘See that he does not.’ George’s eyes bulged with fury. ‘Do you remember when the Prince of Wales planned to leave Hanover for Prussia without my consent, when he thought to go there and marry the King of Prussia’s daughter? Well ... then he encouraged it. Without consulting me, this man encouraged my son to go to Prussia and marry his daughter. That is not all. There was a time when he kidnapped Hanoverian guards for one of his regiments. I tell you, Townshend, this man is a menace to the world.’

‘Your Majesty, with your permission I will write and tell him of your displeasure, but both these matters happened some time ago and have perhaps been forgotten by His Majesty of Prussia.’

‘Leave it to me,’ commanded the King. He was not going to have Townshend nip this quarrel in the bud with one of his bits of diplomacy.

* * *

When the King of Prussia received the letter of complaint from his cousin he was delighted.

He stormed into his wife’s apartment where she was taking a little refreshment and roaring with rage cuffed one of the Queen’s pages and sent him to bring his son and daughter to his presence.

‘Your brother!’ he shouted, throwing the letter he had received from George into the bowl of soup.

Sophia Dorothea picked it out daintily and read it. ‘George Augustus is like you,’ she said. ‘He longs for a fight.’

‘Don’t compare me with that popinjay, or I’ll kill you.’

She put her head on one side. ‘That would be a rather strong action to take,’ she said. ‘Surely I have often done much more to offend you than make such a comparison.’

He approached her, his hand raised; she smiled at him; so he contented himself with spitting into her soup.

‘That,’ she added, placidly, ‘will not I fear improve the flavour.’ She began to read her brother’s letter, and laughed. ‘George is such a fool,’ she said.

‘So you have sense enough to see that! ‘

‘And you,’ she added, ‘are a brute. Between you, you should manage to enjoy your correspondence.’

‘Enjoy! I tell you that if I had that little brother of yours here I’d take his neck in my hands and choke the life out of him.’

‘Don’t be too sure he’d let you do it. He’s something of a soldier, you know. And what he lacks in sense he makes up for in courage.’

‘Then he has to have a lot of courage.’

‘He has.’

The Crown Prince and Princess Wilhelmina entered. Their mother glanced at them anxiously; in spite of the ill-treatment they received from their father they did not appear to be unduly afraid. Blows had become commonplace to them. She wondered when Fritz would turn on his father; as for Wilhelmina, whatever marriage she made she could not find a husband to ill-treat her more than her father had.

‘Come here, you devil’s brood,’ he cried.

‘Aptly named,’ put in the Queen.

‘I was referring to you, Madam.’

‘You are unusually modest. It is your custom to exaggerate your own performance.’ Sophia Dorothea always attempted to turn his attention on herself and away from her children; they were aware of it and loved her for it; but they were so accustomed to the wild life led in their father’s palace that they were prepared for violence.

‘And what are you grinning at?’ he demanded of his daughter.

‘I assure you, Father, that I find very little to smile at.’

He lifted his hand and struck her but it was a mild blow compared with those he was accustomed to deliver.

‘This fool of an uncle, your mother’s brother, has been writing to me again. It seems he’s annoyed because we won’t have his daughter here. You’re not going to marry this girl, I tell you. I’ll not have her walking about my Court with her nose in the air making trouble. I don’t hear very good accounts of your cousins in England.’

‘At least,’ said the Queen, ‘my brother was against the match between Frederick and Wilhelmina.’

‘If you hadn’t been such a prattling fool, woman, we’d have that girl of yours off our hands and your brother would be paying the cost of feeding her instead of me.’

‘The fact is,’ put in the Queen, ‘that George Augustus wants us to take his daughter but won’t take ours.’

‘Well, he has some sense after all. He wants to get a girl off his hands and so do we.’

Wilhelmina flinched and the Queen said: ‘Although it would be a good match for Wilhelmina to marry the Prince of Wales, I should be desolate at losing her.’

The King threw back his head and laughed. ‘You fool!’ he shouted. Then he turned to his daughter. ‘Do you think I should be desolate too? Do you?’

‘No, Father,’ answered Wilhelmina. ‘I know you would be glad to be rid of me. It would save you working out so often how much it costs to feed me.’

He caught her by the ear. She stood very still because the more she moved the more painful it would be.

‘Well,’ said the King, releasing her, ‘it would save me time as well as money. But they won’t have you, daughter. The King of England won’t have you, and the Prince of Wales does not want you either.’

Wilhelmina said with some spirit: ‘He has written to say that he is eager to marry me. He has even said that he is foolishly in love.’

The King laughed again. ‘Foolishly. He admits that. The young man has never seen you.’

‘Perhaps accounts of my life here make him feel he would like to rescue me.’

The King was bewildered. Wilhelmina was growing like her mother. She was showing some spirit. She would have to be married soon. He did not want to have to contend with another woman’s sharp tongue.

This thought made him less violent than usual. He turned to his son. ‘And you ... when are you going to marry, eh? You’ll take the wife I find and say thank you.’

The Queen looked anxiously at her son. He was always calm in contrast to his father; it was as though he was only half aware of him as something that must be endured for a while, but not forever. The Queen believed that in her son were seeds of greatness and that the King was aware of this and was sometimes overawed by it and sometimes goaded to even greater violence.

Fritz listened impassively.

‘Well, well,’ cried his father. ‘Don’t stand there like a dummy.’

‘I shall be pleased to marry when a suitable bride is found for me,’ said Fritz.

The King looked frustrated. This family of his would give him no cause to chastise them. Only his wife provoked him, and he did not care to harm her.

‘This fool of a King of England!’ he shouted. ‘Where’s the letter?’

‘A little the worse for a dip in the soup,’ said the Queen, throwing it at him.

It fluttered at his feet; and Fritz picked it up and handed it to his father who proceeded to read it in loud derisive tones.

‘Do you know what I am going to answer this popinjay?’

He glared at them all and went on: ‘I am going to tell him to go back to England where perhaps they are foolish enough to put up with him. I’m going to tell him that if he stays here ... in Germany ... if he writes such letters to me I will take my sword to him and cut off his head and send it back to his dear wife in England who, I understand, he is fool enough to let rule him. I’ll tell him what I think of him. What a family! ‘

‘Your own,’ murmured the Queen.

But the King was too intent on composing an insulting answer to hear her.

George paced up and down his apartment, eyes blazing. Townshend was doing his best to placate him.

‘This madman! ‘ spluttered George. ‘This cousin of mine! How my sister lives with him, I can’t imagine. He’s mad, I tell you. But mad or not he shall not insult me in this manner.’

‘Your Majesty, a note couched in such undiplomatic language should perhaps be ignored.’

‘Ignored. Let him insult me and I ignore him! I tell you this, Townshend, I shall not allow this to pass. Do you know what I am going to do? I am going to challenge the King of Prussia to a duel.’

‘Your Majesty, that would not be possible.’

‘And why, pray?’

Two Kings cannot fight a duel. It has never been. It could not be.’

‘Then we will be the first, for I tell you this, Townshend: I will not be insulted by this man.’

‘Your Majesty .

‘My mind is made up. I shall challenge the King of Prussia and tell him to choose his weapons.’

Townshend looked at his master helplessly; but he could not control him as the Queen and Walpole managed to do.

The King of Prussia was delighted to receive his cousin’s challenge. His family had never seen him in such a good mood. A choice of weapons. He could not decide, he told his wife, whether it should be swords or pistols. He would enjoy firing a shot through his silly heart; on the other hand it would give him even greater satisfaction to slice off his even sillier head.

The Queen shrugged her shoulders; she did not believe for a moment that the two foolish men would ever be allowed to fight in single combat; their ministers would find some way of putting a stop to such antics.

She was right. The King of Prussia’s ministers conferred with those of the King of England and between them they worked out a compromise whereby the two Kings could abandon their foolish project without loss of face on either side.

Townshend, when he did not have to placate the King, was a past master at this art; and so well did he work with the Prussian ministers that in a short time they were trying to bring the two Kings to an agreement about the marriage of the Crown Prince and the Princess Amelia.

This brought satisfaction to George but less so to the King of Prussia. After all, pointed out the latter, George would have one less mouth to feed, he one more, by such an arrangement.

The Queen replied that then they must marry Wilhelmina to the Prince of Wales and although they gained one mouth they would lose one so the feeding bills would not have increased.

The letters went back and forth between Hanover and Prussia. But the situation did not change; each had a daughter of whom he wished to be rid and neither wished to take the other’s daughter off her father’s hands. But at least the plan for a duel was dropped and the two Kings were writing to each other, with the help of their ministers, in civil terms.

George wrote that he would like to see this matter of the marriages settled before he left Hanover; Sophia Dorothea was eager for the completion of what she called the Double Marriage Plan; but the Kings could not agree.

The King of Prussia finally wrote that he would only agree to his son’s marriage to the Princess Amelia if, on that marriage, the Crown Prince of Prussia became the Regent of Hanover.

This George blankly refused; and to the dismay of Sophia Dorothea once more the negotiations came to an end.

There was no longer any excuse for remaining in Hanover. George regretfully had to admit this and Townshend was at his side, urging a return.

‘It grieves me,’ said the King. ‘How beautiful everything is in Hanover ‘

‘Her Majesty the Queen will be eager to have you back,’ Townshend pointed out.

The King’s eyes filled with tears. ‘The dear Queen,’ he said. ‘There is no one who will ever take her place with me, Townshend.’

Townshend bowed his head and knew he had made his point. They would make preparations to return to England without delay.

George presided over his last levee. He wished, he said, that these levees should be held at precisely the same hour every Saturday as they had been during his stay in Hanover. He would not be there, but he would look at his watch and remember that they were assembled in this room. His chair would be empty and they would bow to it as though he occupied it. Only thus could he bear to leave Hanover.

* * *

Caroline was at Kensington Palace awaiting news of the King’s arrival.

She was sorry that he had not stayed a little longer in Hanover. Life had been so peaceful; and she and Walpole had achieved so much. Now the King was on his way home and they would have to be so careful. How easily they had dealt with the tricky Portuguese affair and the even more important Treaty of Seville!

Walpole, who was growing more and more frank, expressed his misgivings because the happy days of the Regency were coming to an end.

She was at the window when she saw the outriders approaching the palace. This must mean that the King could not be far off.

She summoned her family—every one of them, even little Mary and Louisa.

‘Your father is home,’ she said, ‘we are going to meet him.’

‘On foot! cried Anne.

‘Certainly. It is what he would wish.’

She took Frederick’s arm and on the other side walked Anne, her head high so that all would recognize her as the Princess Royal. William, always a little sullen when an occasion such as this one thrust him into second place, walked with his sisters. Through Kensington to Hyde Park, with the people falling in behind them and the cry going up: ‘The King is back.’

When they reached St James’s Park the royal coach was visible and when they reached it, this came to a stop and the King alighted.

He was beaming with joy.

Caroline was thinking how well she knew him. Nothing could have pleased him more than to see his family come on foot to greet him.

He took the Queen in his arms and embraced her warmly, the tears in his eyes. The people cheered wildly.