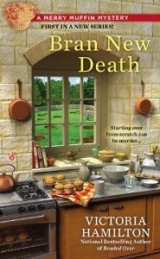

Текст книги "Bran New Death"

Автор книги: Victoria Hamilton

Жанры:

Женский детектив

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Chapter Nine

THE NEXT HOURS were a nightmare, and I pretty much mean that literally. Virgil ordered backup, and they taped off the “scene of the crime.” I say that guardedly because from what I could tell it just looked like Tom had climbed down from the Bobcat, looked into the hole, lost his balance, and fell in. Maybe he hit his head on a rock or something, but why was that murder?

I thought Virgil was being ridiculous until I caught sight of one of the investigators picking up a long, iron rod with plastic-gloved hands from the grass near the hole. He held it up to the light and called Virgil over, pointing to something on it. Like a movie replaying in my mind, I remembered picking it up from the edge of the hole, a long iron rod that was in my way. I had tossed it aside, leaving, no doubt, a nice copy of my finger-and handprints on the thing.

Sugar.

A chill crept down my spine. These people didn’t know me, didn’t know that violence is not in my nature. All they knew was that I had threatened Tom Turner, and now he was dead.

We waited for hours in the police car. One of the police technicians had already photographed our hands, and examined them. I had a couple of scrapes on my palms, probably from clearing weeds away from the garage windows earlier that evening; what would they make of those? Should I explain them, or would that seem suspicious? I stayed quiet. Being examined so closely would make anyone nervous, I say.

Virgil came over at one point and asked for permission to search the castle. If I said no, they’d keep me out until they had a warrant, which, given the circumstances, they would have no trouble getting. I told them to go ahead, but to mind Magic. I had to explain that I meant to be careful that Magic, the bunny rabbit in Shilo’s room, didn’t escape. Finally the sheriff opened the police car door and told us they had bagged some things for evidence, but we could go back in. He was stomping away when I caught up with him and grabbed his arm. I could see the weariness on his stubble-lined face, but he looked at me with grim resignation. Gone was the flirtatious, young guy I had met that first day. I didn’t think I’d see that flirtatious fellow ever again.

“What could you possibly have taken from the castle?” I asked.

“Mostly paperwork. We’ll give you an official receipt. You can get it when you come to the station to sign your statement and give us your fingerprints. That goes for your friend, too.”

In my statement I had already told him about tossing aside the iron bar, which, it turns out, was a crowbar and possibly the murder weapon. My fingerprints were going to be on it, guaranteed, and may well have irrevocably smudged the actual murderer’s prints. “This doesn’t have anything to do with me, Virgil,” I said, tension tightening my voice. “You know Tom Turner was the kind of guy who made enemies wherever he went. I can’t be the only person who was at odds with him.”

He glared down at me. I’m a fairly tall woman, but he was taller. “Look, Merry, I can’t discuss this. I know in the TV shows the cop always speculates on what is going on and shares his feelings with every civilian who’ll listen, but in real life, that would damage the case. It’s for your protection.”

Great. I was being kept in the dark for my own protection. Moodily, I watched him walk away, back to the scene, as the sun climbed and peeped over the top of the forest. Shilo came up and put her arm through mine.

“I’m tired and hungry, Merry. Can we go in and get coffee and food? Poor Magic is probably freaked right out by all the people stomping around.”

And so my day started.

By now, the kitchen almost felt like home, despite its size. Shi and I had dragged some overstuffed wing chairs in and created a cozy nook by the fireplace, which would be lovely on cool, autumn evenings if I ever had the nerve to try to light a fire. New York apartments with real, working fireplaces were well beyond my standard of living, though if you want me to bleed a radiator, I can do that. But the working end of the kitchen was just as it had been. I couldn’t wait until I got all my old baking stuff out of storage and could liven the dull place up a bit.

I mixed up the carrot and apple muffin batters, then began baking. Soon enough I had my four dozen muffins ready to go in the cheap plastic wear I had bought in town, and Shi and I munched a couple of the extras. They were so good; surprising, since I was just estimating the ingredients.

Shilo was going to go into Autumn Vale with me later in the day, but first, despite the tragedy we had witnessed in the night, I wanted to begin evaluating the castle, and figure out what needed to be done. My warm feeling the day before about getting to know my lost family had dissipated; I suppose a dead body in a hole on your property has a tendency to dampen enthusiasm. I now just wanted to sell the darn place and move back to civilization. I know that sounds snobby, but you try being woken up at three am by a lunatic on an excavator who then has the bad sense and worse taste to get murdered.

I felt horrible about Tom Turner, but I hadn’t done anything to him, nor did I know who did. I was nervous, frightened, and worried. And all of that emotion was punctuated by anger. I hadn’t asked for any of this. All I knew was, I needed to get on with the business of getting rid of Wynter Castle.

We stood in the main hall, our voices echoing in the cavernous space as we talked about how to best show the place off to make it saleable. It needed to be warmed up considerably, but I didn’t want to get in the way of its natural beauty. We fell silent as the sun ascended and beamed through the rose window, sending blades of colored light streaming, piercing the gray shadows of the hall.

“Wow,” Shilo said.

I wanted to weep, because that simple ray of light had reminded me of how amazing an experience this was turning out to be. So much beauty and I couldn’t keep it, could never afford to live in this gorgeous place. “I guess I should enjoy it while it lasts,” I said quietly. “It’ll be even better once the rose window is cleaned up.” I made a note to find someone to do that task—there was no way I was going to try cleaning a window twenty feet off the floor—and also to see if I could hire someone cheap to do the yard work. I wondered how much this was all going to cost. Gogi, had been right: if I was going to stay any length of time at all, I needed to get a flow of income going.

We worked for a few hours removing Holland covers, rearranging furniture and assessing the castle’s strong and weak points. The biggest task was finding a way to get the Holland cover off the chandelier, but at long last we managed it with minimal damage to ourselves and the long-handled pruning shears I discovered in the pantry. As the fabric cover floated down to the hall below, we stood for a long moment, looking down on the chandelier from the gallery. It was amazing, hundreds of crystal shards dangling from gilt-coated brass. I’d have loved to turn it on, but thought I should get an electrician to look it over first.

Then I went to my uncle’s desk, which was in the smallest extra room on the second floor. He had a cluttered, dusty, old rolltop desk with an array of nubby pencils, inkless pens, stained erasers, and rulers from a variety of commercial sources, including “Autumn Vale Community Bank; Where Your Hard-Earned Dollar is Safe and Secure!” It looked to me as if someone had rustled through it lately, and I thought that this was probably one spot the police had checked.

I was going to have to go through all the junk piece by piece, but not today. I idly sifted through, noticing Autumn Vale Community Bank check records and account books, bills from local utilities, an unopened envelope addressed to Turner Wynter Global Enterprise, and one curious little torn memo in scrawled handwriting . . . someone had written “Call Rusty about mobi . . .” and the rest was illegible. It had to be my uncle’s handwriting . . . who else would leave a handwritten note in his desk?

I couldn’t do any more though. Time was flying.

Shilo and I got into her rattletrap—the miles were adding up too quickly on my rental, especially for someone who didn’t have an income—with the four dozen muffins for Golden Acres. As Shilo drove, I pointed out the by now well-known way into town. The castle was above the town, to some extent, and when we rounded a curve I told her to pull off to the side for a minute.

I got out and walked to the edge of the road, where there was a break in the tree cover. Shilo joined me. The town was laid out like a little animated map, the main street, Abenaki Avenue, pretty much a straight shot through town, and the streets off it curving along rising elevations. This was the place I had stopped the morning I arrived; I had been just a couple of miles from the castle and hadn’t known it. A distance away along the valley, I could see some kind of industrial business: an office trailer, a big warehouse, a machine yard with lots of heavy machinery lined up, and stacks of construction materials. I wondered if that was Turner Construction, or Turner Wynter, whatever it was called. What was going to become of that business now? It must already be in tatters, with my uncle gone, Rusty missing, presumed dead, and now Tom gone, too.

I shared my thoughts with Shilo, and then said, “Poor Binny. She lost her dad, and now she’s lost her brother.” I got back in the car and we made our way into town. I directed her to Golden Acres, and dashed in to give the muffins to the kitchen staff to disperse. I’d visit with Gogi and Doc another day. As we then drove down Abenaki Avenue, I saw that the bakery was actually open.

“Should I go in and say how sorry I am to Binny?”

Shilo guided the car to the curb and parked. “I’ll go in with you.”

I felt trepidation as I entered. There were a half-dozen people already in there. Given what had happened to her brother, I was surprised Binny was there and open for business as usual. Her relationship with her brother was something I knew little about. The baker was serving customers and she didn’t seem any more or any less grumpy than she had the last time I was in there. I waited my turn, and, with Shilo by my side, came up to the counter. “Binny, I just . . . I wanted to tell you how sorry I am about what happened to your brother.”

She swallowed, and tears welled in her eyes. She simply nodded. I was relieved. I’d been afraid, after the confrontation I had with her brother, that she’d think I did it. Her face was white, though, and it looked like she was just holding herself together by a thread.

A hunched-over fellow of indeterminate age, thin as a rail, and with a sparse, fine covering of hair on his head, said, “I bet it was them two guys who showed up last year asking all kind of questions. That was just before your dad disappeared, Bin.”

I watched him with interest; he was young, probably about Shilo’s age, but had the stature of a little old man, and I wondered if his hunched look was a congenital condition or just a mannerism.

“Gordy, that was a year ago,” Binny said. “You can’t possibly think they did something to Tom.”

“But they were real suspicious, asking all kind of questions about your dad’s business, and even about Tom.”

She shrugged helplessly. “I don’t know,” she said, her voice thick with unshed tears. “I don’t understand what’s going on anymore.”

Another local who had just entered, a fellow about the same age as Gordy, chimed in, “You gotta know it was probably Junior Bradley who did Tom in.”

“What are you talking about, Zeke?” Binny asked sharply. “Tom and Junior were best friends.”

“Who is Junior Bradley?” Shilo said.

Gordy, who had been watching Shilo with that hopeless admiration most men felt for her, said, “Junior is the zoning commissioner in town. Him and Tom were good buddies, but they had a big fight the other night at the bar up Ridley Ridge.”

“What was the fight about?” Shilo asked.

“A girl,” Gordy said.

Zeke chimed in. “Yeah, Tom and Junior were both after Emerald, one of the dancers at the bar. They got into it, and Junior threatened Tom. Said he’d better leave Emerald alone if he knew what was good for him.”

I had been right; there were others out there who had been less than thrilled with Tom. “Were you guys there?” I asked.

Both men turned crimson.

“Uh, nope. I heard about it from a friend,” Zeke said, his Adam’s apple bouncing up and down his throat, his gaze turned away from all of us women. He stared steadily at the wall of teapots.

“Or, the awful event could be connected to . . . the Brotherhood,” Gordy said, his tone sententious.

Both Zeke and Binny rolled their eyes.

“The Brotherhood?” I said.

“You’ve got to get off that kick,” Zeke replied to his friend, with the air of someone who has said the same thing many times before. He turned to me. “The Brotherhood of the Falcon is a bunch of old farts who sit around and make exclamations, or declamations, or whatever they do.”

“Declarations,” Binny said. “The last one was something about keeping the Brotherhood all male, as if any women would want to join! Zeke’s right, Gordy. Those are just a bunch of old guys drinking beer and remembering their glory days.”

“I don’t know,” Gordy said, his tone slow and doubtful as he nodded and winked with that knowing expression of someone who is in on a deep, dark secret.

“For God’s sake, Gordy . . . Dad was a member!” Binny said.

“Well, I heard they’re connected to the Freemasons, and you know who they are!” He was clearly waiting for someone to take the bait, but no one did and he looked disgruntled.

“Anyway, I’ve got work to do,” Binny said, and whirled around, stomping back to her ovens without another word.

Shilo and I stood and stared at each other for a moment, uncertain of what to do. I wished I could help, but I was the last person who could offer Binny comfort. I looked to the two locals. “Well. I guess we’ll be going.”

“You’re old Mel Wynter’s niece, right?” Gordy said. “The one who’s inherited the castle.”

“And you were there last night when Tom was killed, right?” Zeke said, looking me over closely.

“Uh, yes.”

“What’d you see?” Gordy asked softly, glancing over at the kitchen.

“Not a thing,” I said, using the tone that forbids further discussion. “Did you guys know my uncle?”

“Nah,” Zeke said. “But every kid in school snuck out to the Wynter estate and tried to look in the windows. I got chased away from there a couple of times by old Mel with a shotgun.”

Lovely. “We have to go,” I said. But I didn’t move. These guys probably were my best source for local info at that moment, I realized. It would be stupid to ignore that. “As we were coming in to Autumn Vale, we noticed a warehouse property just past the edge of town. Is that where Turner Wynter is located?”

“Well, it’s Turner Construction, yup,” Zeke said.

Binny started banging pots around in back, and I heard one loud sob. If I was a friend, I’d barge back there and comfort her, but I didn’t quite know what to say to a girl who didn’t seem to want or need consolation, preferring to hide in her kitchen and cook. Or maybe I did know too well what that was like. I had done the same when Miguel died. Gordy gave a look, then hitched his head toward the door. Shilo and I followed him and Zeke out to the street.

“Don’t go mentioning Turner Wynter around Binny,” Gordy said, joining us at the curb.

“There’s a lot of bad feelings there,” Zeke added. “Tom was sure in a tizzy about it all, the lawsuits and such. Don’t know what’ll happen now that they’re all dead.”

“I’ve heard about the lawsuits; what were they about?” I asked, interested in the gossips’ take on the situation.

Gordy and Zeke explained in their tag-team manner that there was once a plan for Turner Wynter to develop Wynter Acres, using some of the land attached to Wynter Castle. It devolved into lawsuits slung at each other, with both Rusty Turner and Melvyn Wynter claiming that the other man had cheated him. Other than that, they didn’t appear to know the details of who sued who, or about any possible resolution.

“Y’know, you’ll probably have to settle the lawsuit,” Zeke said, hitching his thumbs in the belt loops of his jeans. “Along with Binny.”

“Me?” I squawked, taken aback. “It has nothing to do with me.”

“Your land now, your lawsuit,” Gordy said, rocking back on his heels.

“But there’s no one left to continue against!” Shilo exclaimed.

I saw both young guys shutter like blinds, and their gaze became shifty.

“I guess that’s so, isn’t it, Zeke?” Gordy said.

“Mighty interesting, that,” Zeke said. “Mighty interesting.”

And with that, the two cast me one long, thoughtful look, and ambled off down the sidewalk with their heads together, chattering like gibbons. Great. I felt like I was now back in the center of some kind of local suspicion.

“We’re going to visit a certain lawyer,” I said to Shilo.

Silvio was in, and Shilo and I entered, but this time he seemed out of sorts. “What do you want this time, Miss Wynter?”

And he had been so friendly last time! “I take it you’ve heard about Tom Turner’s death in my yard?” I said, steeling myself against hurrying in the face of his irritation.

He nodded.

“People are suspicious, it seems, of my connection to the whole case because of those darned lawsuits. Can’t we resolve things, now that it’s all water under the bridge?”

He sighed heavily, very much the put-upon legal eagle. “There is nothing I can do about it, I told you. Nothing to do with me.”

“The point is, it is a complication in the estate.”

“Yes. It’s unfortunate. Rusty and Mel started out working together on Wynter Acres, and it all seemed so promising. It was to be a housing development meant to attract retiring baby boomers who wanted to live in the country but have the convenience of condo living. Then Mel accused Rusty of cheating him and it all went to hell in a handbasket. Though I could not get legally involved, I was trying hard to mediate between those two bullheaded, old men.”

“Until Rusty disappeared and Melvyn died.”

He nodded. “I don’t even know where everything stands. It’s all in limbo until we know the legal determination in Rusty’s death or disappearance.”

“In other words, it could go on forever,” I said. “What does that mean to my wanting to sell the estate?”

He shrugged.

Anger was building up in me. “So you can’t even tell me if I’ll be able to sell the estate, is that it?”

“Oh, you should be able to sell, but there will be conditions attached to the sale.”

Great. Buyers just love conditions. His next appointment, a young woman, entered, and we were forced to leave, me feeling kind of huffy about the whole thing.

“We may as well find this library folks keep telling me about,” I said. Shilo and I walked the streets of Autumn Vale, the locals watching and whispering about our every step.

Finally, along a side street in the downtown section, up a sloped alley, I saw the sign I had noticed before, hanging out from the building. Autumn Vale Library it read, in curly script that looked hand painted. According to the placard attached to the wall it was open, so Shilo and I strolled up the wheelchair access ramp to the door and entered to the sound of weeping.

Shilo gripped my elbow, as full of consternation at the woeful, echoing sounds as I. It was like the place was haunted by a mournful ghost. As my eyes adjusted to the dim light, I looked around the cavernous, gray room lined with bookshelves, most not above shoulder height, and finally saw what looked like a desk.

We approached. Behind the desk was a girl in a wheelchair. I say “girl” because at first glance she appeared to be no more than ten or eleven. But on closer inspection, as she turned red-rimmed eyes—beautiful, luminous, huge eyes—toward me, I could see within them a woman’s full measure of pain.

“Are you okay?” I asked my voice faltering.

She stared at me for a long moment, then said, “When one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of a book, but translated into a better language.”

Shilo said “Huh?”

But I’d heard or read the quotation before. I closed my eyes; it took me a moment, but I finally replied with the next, more famous part of it, my voice softly echoing up into the gray shadows of the library’s upper reaches. “Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.” It was from a prose piece written by John Donne, and was the source of Hemingway’s most famous title.

The girl bowed her head for a long moment, and we were silent. But she looked up, and said, “It’s true, isn’t it? He’s dead. Tom Turner is gone.”

“You were friend of Tom’s,” I said.

She nodded, her large, gray eyes fixed on me. “He was a good man, despite what others say. Despite what you may think.”

“You mean because of my run-in with him?”

She nodded.

“You know who I am.”

She nodded again.

“I just wanted him to stop digging holes on my property,” I said, on a sigh. “I really wish it hadn’t ended this way. I’m sure you feel the same.”

“I do . . . I’m so s-sad! That’s where he died, isn’t it?” Her breath caught on a sob, but she was trying to be brave. I could tell.

It was my turn to nod.

Shilo was looking back and forth between us. “I think I’m going for a walk,” she said.

Once Shi was gone, the girl said, “I suppose you’re here to learn about the Wynters of Wynter Castle.”

“I’m in no hurry,” I said. “That can wait. Why don’t we talk about Tom Turner, first. I know so little about him or anyone here. You know who I am, but I don’t know who you are. What’s your name?”

“Hannah,” she said. “It means ‘God has favored me.’”

She smiled through tears, and she was beautiful. I pulled a chair over to sit beside her, and we talked. Hannah was a little person, tiny of frame and fragile as a bird, with pale skin like bone china. But her heart was huge, too big for her small frame, and she seemed filled with an eager grace. I don’t know how else to express it. A beautiful yearning poured from her, expanding to fill the dim recesses of her library.

“How did you come to work here, in the library?”

“It’s my library; I applied for a grant, I talked them into it, and I got the place renovated. I’ve always loved reading,” she said. “When I was a kid, I read a book The Little Lame Prince and His Traveling Cloak. It opened up the world to me. I’ve been to Cameroon with Gerald Durrell, and to Yorkshire with James Herriot. Isak Dinesen showed me Kenya. I’ve been around the world with books as my traveling cloak.”

“I know exactly what you mean,” I said. “I’ve lived and breathed in Regency England with Jane Austen. I’ve walked the Yorkshire moors with Emily Brontë and the streets of Victorian London with Charles Dickens. Books are a marvelous transport. Tell me about why you were crying for Tom Turner.”

Her smile illuminated the shadows. “We were going to be married.”