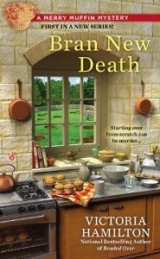

Текст книги "Bran New Death"

Автор книги: Victoria Hamilton

Жанры:

Женский детектив

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Chapter Twenty-one

I WOKE UP the next day sure of a few things. First, I needed to speak to Junior Bradley again and try to find out what he and Tom Turner had really been fighting about. At the same time, I needed to know about the faulty plats and plans I found at Turner Construction. Who approved them? Who loaned the company money for construction based on them? What lawsuits were truly extant when Melvyn died? Did it have anything to do with those faulty plans, I wondered.

I also needed to get a handle on who I thought might have killed Tom Turner. Despite everyone’s belief in Virgil Grace’s ability to solve the murder, I could not just stand by and wait. After all, nine months later he still had not figured out if my uncle’s “accident” was really an accident. Maybe I could even help, with an outsider’s viewpoint. I wondered what the buzz was in town, especially now, with this body we found yesterday.

As Shilo snored on the other side of the Jack and Jill bathroom door, I showered and dressed comfortably in jeans and a soft, V-neck T-shirt. Then, cup of coffee in hand, I exited the front door, descended from the terrace, and walked down the weedy drive to try to get a better view of the castle and decide what needed to be done first. I turned and squinted, looking over my inheritance. As I had begun to realize, I was going to be at Wynter Castle longer than I had anticipated, and had better start planning for a winter spent in upstate. But I had a couple months of outdoor time left before the unpredictable winds of November set in.

The exterior itself was attractive: old, cut stone, square facade with a turreted look to the rounded extensions at either end, and Gothic-arched windows. The entrance, centered on the long, flagged terrace that wrapped around the ballroom on the west side of the castle, was bland, though, even with those amazing oak doors. It needed something to set it off, to make it stand out. Maybe gardens or potted plants and statuary. The terrace, I had discovered, extended all the way along the far side, and the ballroom’s French doors opened out onto it. That, too, needed something to break up the long expanse.

How was I going to afford any of the upgrades needed? I had to make or borrow enough money to bring Wynter Castle up to a degree of attractiveness for potential buyers. The property would only appeal to someone who could afford to gamble. Wynter Castle was too far away from New York City to make it a spa retreat, and there was absolutely nothing nearby to make it a desirable destination from a tourist’s aspect. Investors would cringe. It needed a buyer with imagination and bucks.

I turned away and wandered the property near the castle, avoiding what I now thought of as the death hole, where crime-scene tape still fluttered from hastily erected fence posts. It was only early September, but after a couple of very cool nights the leaves were beginning to get that desiccated look from late-summer stress and nearly autumn change coming on. A blue jay shrieked at me from a cluster of brushy shrubs that had grown up in the long grass.

When was my grounds crew going to show up? They never did phone me. Had I done the right thing, hiring Zeke and Gordy to mow the fields? They didn’t strike me as the brightest bulbs in the package, maybe twenty-five-watt in a hundred-watt world, but how bright did you have to be to mow a yard? That sounds snooty, but I was getting irritated at the slow pace of life in Autumn Vale. No one seemed to be ready to hustle. The grass, or hay, or weeds—whatever the mess was—had to be taken care of and soon, because . . . well, because I needed to see progress.

I walked past the excavator parked among the filled-in holes, thinking of all the damage Tom had done, and wondering why. He could not possibly have believed that old Melvyn Wynter had buried his father, not when he was digging all the way out to the edge of the property. It didn’t make a bit of sense!

Sipping my coffee as I scanned the edge of the woods, I thought I saw a patch of orange. Was Becket back? In all the flurry of the day before, I had almost forgotten the poor, limping cat! I edged closer, but the animal didn’t move this time. My heart started pounding, and my stomach lurched. I walked faster, speeding to a trot. It was Becket; it had to be!

It was. He wasn’t moving, but he was still breathing a labored, slow pant. As I knelt by him, he opened his eyes, meowing fiercely, then wailing and thrashing about. As I leaped to my feet and backed off, he focused and met my gaze; his meow gentled to a question. I hadn’t had a cat in years, but I knew that sound. He needed help.

Tossing the junk-store coffee cup aside, I knelt again, and scooped him up. He was wearing, amazingly, a collar, with a cheapie plastic tag attached; incredible that it had survived nearly a year! “Becket” was written on the cardboard insert. “You poor fellow,” I murmured. There were no cuts or bites that I could see, but he didn’t look right. He was a big cat, long-limbed, but skinny, far too thin, and his orangey fur was matted and dull looking. As I carried him, his head lolled over my arm, his eyes open but filmed.

The next hour was a blur. I took Becket in to the kitchen and laid him on a towel in one of the chairs by the fireplace, then got Shilo up. We gave him a drink of water, which he lapped at thirstily before collapsing again in exhaustion. I got ready to go, organizing my day as quickly as I could as I worried about the cat.

Even through the thick walls of the castle, I could hear the heavy engines of police vehicles arriving; they were coming to finish up with the encampments, as Virgil had promised. I wrapped Becket in the towel and carried him outside to the car, as the sheriff and his crew set up their base of operations, but I didn’t have time to talk. I handed Shilo the keys to the rental and we took off, with me holding Becket and Shilo driving. Shi had been able to get ahold of McGill, who told her where the only vet in town was located. She had explored a lot already, more than I had, mapping out the town in her retentive brain, and she brought me to a little clinic that took up one end of a redbrick, modern strip mall that also had the town waterworks department and other municipal offices in it.

The vet was a young Asian-American woman, Dr. Ling. After she heard my remarkable story and confirmed that though he was not my cat, I was going to be responsible for the bill, she ordered me to leave Becket there in the treatment room. As we left, I heard her call out to an assistant to start a fluid IV. Becket was in good hands.

Again, life in Autumn Vale had changed up my day in weird ways.

Shilo told me she was going to hitch a ride back to the castle with McGill, who was headed out there to fill in more holes—at the rate he was going, he’d be done by the next day—so I was free to do what I needed to do. I had at least thought well enough ahead to throw my muffin tins in the car, so I headed down to Binny’s Bakery to see if she would mind me starting the muffins a little early.

I entered to the now-familiar clang of the bell over the door and was once again taken by the collection of teapots, which I examined with interest. It wouldn’t be long before I had all my stuff from storage, and then I was going to have to deal with my own dozens of boxes of teapots and teacups. Binny came out from the back, wiping her hands on a towel, and said, “Oh, it’s you!”

“Yeah. Could I start my baking a little early?” I explained why.

She had an odd look on her face, and nodded. “Sure.” She paused, tapping on the countertop and biting her lip. In a rush, she said, “Maybe you can do me a favor?”

“No problem,” I said. “You’ve been so generous, I’d love a chance to do you some payback.”

“Would you mind the store for an hour while I run an errand? You know how to use a cash register, right?”

I didn’t then, but I soon learned. A half hour later, she threw some goodies in a bag and took off out the back door. No explanation. Boyfriend, maybe? Not my business. I made two large batches of muffin batter—banana bran and applesauce, since those two seemed to be going over best—popped them in the oven, and set the timer, as a couple of customers came in. It just happened to be Isadore Openshaw and another, middle-aged lady.

“Hi, what can I help you with?” I said, in my brightest customer-service voice.

Isadore looked like she’d swallowed an air bubble, kind of pained and grimacing, but the other woman smiled and cocked her head to one side. “Who are you? Where’s Binny?”

I explained who I was as Isadore stared fiercely at the goodies in the bakery case. “I’ve met a lot of folks, including Miss Openshaw,” I said, “but I haven’t met you yet.” I stuck out my hand over the counter.

“Well, isn’t this fascinating! I’m Helen Johnson of the Autumn Vale Methodist Church,” she said, taking my hand in a firm, if clammy, clasp. “I visited your uncle many times, to take him soup and ask him if he’d like to join our congregation. We have such wonderful seniors’ programs, with euchre nights, shuffleboard, and bus trips to Amish country!”

I stared at her for a long moment, nonplussed, wondering what kind of reception she’d gotten from my cantankerous uncle. Hopefully she wouldn’t have a story about being chased away by a rifle-wielding madman. She was one of those born church ladies, but in tweed capris instead of the expected skirt, topped by a silk blouse and pearls. Sensible sandals and socks, visible under the counter’s pass through, finished the ensemble, and a hat topped her billowy nest of gray hair. “I’m pleased to meet you. How did the visits with my uncle go?”

Isadore snorted and stared ferociously over my head.

Helen glanced over at her with a frown, then looked back to me. “Well, he was not pleased to see me. Tell me . . . was he suffering from Alzheimer’s, perhaps? Every single time I went out, he asked the same question; what did I think I was doing there? He was so terribly confused. I never knew what to tell him.”

I took a deep breath to keep from laughing. The timer dinged, and I rushed to pull the muffins out, then returned to the counter and explained to the ladies what I was doing there: making muffins and minding the store. Helen clasped her hands together. “Oh, muffins! My darling mama told me about your wonderful muffins. She lives at Golden Acres, you know, and feels fortunate. Mrs. Grace is such a wonderful woman, a real social leader in this town. Even though she doesn’t go to church.”

I was exhausted by her relentless cheerfulness, and relieved when she bought two ricotta-stuffed pastries, while Isadore chose a gooey éclair. I boxed them up.

“One day when I was out there,” Helen said, lingering while Isadore waited at the door, tapping her patent leather shoe on the step, ”. . . at the castle, you know, there were two strange men, but I didn’t see Melvyn. I wondered and wondered about those men, you know, and I heard rumors they had been in town that day, but I never saw them again.” Her dark eyes were bright with curiosity, the perfect image of a nosy Nelly.

“When was that?” I asked.

“Oh, Lord, let me see; when was that?” She looked up in the air and cocked her head. “Was that before the fire in the woods behind the church, or after? After, probably. No, before.” She paused and frowned down at her sandals. “No, it had to be after the fire. I remember now! A week or so after. So that would have been, let me see . . . last October? Almost a year ago.” She nodded sharply, triumph on her round, cheerful face. “Late October of last year.”

I was exhausted with her thought process, and Isadore was clearly ready to go out of her mind, but I wasn’t done yet. “What did the men look like?”

“Well, now, they weren’t very friendly. They had on suits, black suits, and they had a black car.”

“Old? Young? White? Black? Tall? Short?”

She shrugged. “I don’t remember, dear.”

“I have to go to work, Helen. I’m late! Mr. Grover won’t have a clue how to open.”

“Hey,” I said to her, “your employer came out to the castle yesterday, Miss Openshaw. Simon Grover was with the volunteer fire department, giving support to the police.”

Isadore didn’t answer, but Helen’s eyes widened. “Oh, my, yes! I heard about the corpse in the woods near you. Was it Melvyn’s body?”

Taken aback, I said, “Uh, no, Melvyn’s body was never missing.”

Isadore was practically dancing in place. “It’s ten-o-seven, Helen! I’m late. I thought you needed money at the bank, and then had to get to choir practice?”

Why didn’t she just head on to the bank and let Helen follow? Maybe it was like women in a bar who needed to go to the washroom; they traveled in duos. Or . . . maybe Isadore didn’t want me talking to Helen alone?

“Oh, heavens, yes! Well, I’m glad the body wasn’t your uncle’s, dear.” With that, both women left the store, and Isadore took her friend’s arm as they marched off down Abenaki.

I pondered that weird conversation as I packaged up my cooled muffins. Was it my imagination, or did Isadore get even more agitated when the two men at my uncle’s place came up in conversation? I was now certain she knew something, but concerning what? My uncle’s death? Both she and Gogi had questioned how it happened, but would Isadore have even talked to me about it if I hadn’t caught her examining the scene?

The bakeshop got busy, and more than two hours dragged by, with me having to figure out what every item was priced at, and where a fresh supply of bags was, and how to construct the bakery boxes. When Binny slogged into the shop at almost one, I was tired, grumpy, and puzzled.

She held up her hand, as she came from the back room tying a fresh white apron on. “I know, I know; I was gone longer than I expected. Sorry. Hope you weren’t swamped.”

Mollified, I replied, “Well, it was longer than I expected. But I sure met a lot of locals! If you need help, I’d be happy to fill in for you sometime. I was going to offer rental money for the use of your ovens, but maybe you’d consider a trade of services, your ovens for my time?” It had just come to me that moment, and since my mouth often moves as quickly as my mind—or even quicker—I made the offer as I thought of it. It would save me money I could use toward the castle refurbish.

“That would be good.”

She looked tired and bewildered, and I wondered what that was all about. Maybe she had a boyfriend she wasn’t talking about, and she had met him but they had had a fight. That was a whole lot of “ifs,” though. Dinah Hooper walked in the door at that moment, and Binny watched her.

I hung about for a few minutes, and we chitchatted, but neither woman said much of interest. Dinah was talking about her decision to open a floral and décor shop, while Binny was feverishly dashing around, clanging pans together, as customers came in to the store. I couldn’t spend too long, not if I wanted to do everything that I needed to do, so I left.

I was mystified.

Something had upset Binny. Whatever it was, it wasn’t anything she could share with me. I went and had a bite to eat at the Vale Variety. My sometimes working/sometimes not cell phone kicked in with a text message, telling me that Shilo and McGill had had lunch with his mom, and were now on their way out of town to the castle. Lunch with his mom? Wow, talk about speed dating. In all the years I had known Shilo, she had never latched onto a guy so thoroughly. And McGill seemed to return her interest in spades.

During our many conversations, I had learned that McGill had lost his wife around the same time I had lost Miguel. He seemed to be open to new romance though, while I was mired in the past, swallowed alive by my sense of loss, still, after seven years. How was McGill managing, even with a girl as extraordinary as Shilo? Most widows and widowers that I knew of moved on more quickly than I was able to, though. All around me, folks were getting together and going on with their lives, while I still mourned the only man I had ever loved. Miguel was going to be a hard act to beat, and maybe that was my problem. I still measured every man I met and had a passing interest in against his perfection.

I checked in with the vet’s office after lunch, but though Becket was doing better, he wasn’t quite ready to leave. I could practically hear dollar bills winging their way out of my wallet. I decided I may as well take the muffins to Golden Acres, so I drove there and parked on the sloping road, then circled the building to the back, where I delivered the baked goods to the kitchen.

Then I went through to the old section of the retirement residence. There was some kind of event going on in the community room; I could tell by the laughter. I followed the sound, and entered through the pocket doors. Hannah was sitting in the middle of the room surrounded by old folks. Books were piled around, and she was clapping at something someone had just said.

“Merry!” she cried. “You’re just in time! It’s Random Quote Day.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“It’s a game,” she said, her huge eyes sparkling.

Lizzie was sitting in the corner talking to Mr. Dread, and ignoring everyone else. I let her be for the moment, and joined the turmoil that swirled around Hannah, a virtual senior tornado of oldsters grabbing books, showing them to others, tottering around the tiny librarian with wheelchairs and walkers.

“It’s your turn,” she said, and tossed me a book. She named a page and line number swiftly. “Read it now!”

I didn’t have time to protest, nor did I notice the book title, so, with everyone eyeing me, I opened to the page and scanned down to line seven. “‘It is not time or opportunity that is to determine intimacy; it is disposition alone. Seven years would be insufficient to make some people acquainted with each other, and seven days are more than enough for others,’” I read out loud. How apropos of our fast friendship! And I recognized the quotation. I closed the book: Sense and Sensibility, Jane Austen. Of course. I eyed Hannah suspiciously and she beamed a bright smile in my direction. That was no random quote; the minx had planned it in case I showed up, knowing my love for classic English literature, and zeroing in on the appropriate quotation.

“Who’s next?” she said.

I wanted to find Gogi, but I murmured to Hannah, as I passed, “Can we talk before you leave?” and she nodded.

In the reception area the same girl I had met before—and whose name I had forgotten—was ably filling her post as combination watchdog and phone answerer. “Is Gogi Grace available?” I asked her.

She turned her brown-eyed gaze on me, and tears welled. “I’m sorry,” she said, her light Irish accent soft and vibrant. “She isn’t able to see anyone at this moment.”

“Is everything okay?” I asked, a little alarmed by her evident sadness.

She glanced around and leaned forward. “Everything is just fine, but . . . she’s . . . she’s having a vigil for a terminally ill patient right now, someone who has no family. She’s asked not to be disturbed.”

“That’s so sad! Who is it?”

She shook her head. “It’s no one you would know. The lady has been confined to her bed for years; she’s 103. No one left even remembers her. But Mrs. Grace won’t let her leave alone.”

“Thank you. I . . . I wish her well.” I turned away and spotted Lizzie, standing partly shrouded by the potted fern by the door. She stared at me, her eyes dark and red-rimmed. The girl had been crying, and I wanted to know why. “Do you want to talk?” I asked. She nodded. “Let’s go outside.”

Chapter Twenty-two

WE WALKED OUT to the benches out front; that was as good a place as any, since I hoped to catch both Hannah and Gogi, should she become free. The clouds had gathered and concealed the sun, with an ominous darkness in the distance. I wished I had a sweater. A cool breeze swept up the sloped road. But Lizzie—wearing a sweatshirt that was emblazoned with a slanted, homemade logo in fabric paint asserting that “AVHS Sucks!,” probably a reference to her high school—seemed comfortable. We sat down on one of the empty benches and she thrust her legs out in front of her, slouching back with her arms folded over her chest.

“How are you doing?” I asked, to kick-start the conversation. With a moody teenager, I could wait all day before she would do it.

She shrugged.

“You going back to school yet?”

“Still suspended.”

“What did you do, anyway?”

“They didn’t like my sweatshirt.”

Surprise, surprise. “How’d you sleep? I hope it wasn’t too bad, thinking about what we found in the woods.”

She shrugged again. “I don’t care about that.” She paused, but then went on, saying, “My mom came back to the house this morning.”

“Oh?”

“Why is she suddenly pretending like she cares?” Lizzie asked, kicking at the grass that edged the walkway.

“Maybe she really does care, Lizzie. I know it doesn’t feel like it, from your aspect. Has she messed things up between you?”

“We were doing fine until she hauled us back here. Then she just handed me to Grandma and took off.”

I didn’t know what to say to that, because it wasn’t my place to defend either woman, nor did I know enough of the story to know who was in the right or who was in the wrong. “Was she trying to straighten things out, maybe? Did she figure you needed a safe place to live until she could do that?”

“Yeah, well, she said she’d be back for me and that we’d be able to live together again, and then she just . . .” Lizzie glared up at the sky.

I stayed silent, not sure if pointing out that her mom seemed to be trying to keep her word would help. From the conversation I had overheard, it appeared that she had come back and wanted Lizzie to live with her, though the grandmother was blocking the effort.

“Did they find out who that guy in the woods was yet?” she asked.

“Not yet. They’ve eliminated one local guy, Rusty Turner, but haven’t nailed down who it is.” I waited a moment, then said, “I’m sorry for dragging you into it, Lizzie. If I had known . . . but of course, I didn’t. We never would have found him if it wasn’t for you. It was a good thing to do.”

Watching my face, she said, “That cop, he wondered if you, like, led me to the place with the body.”

I was taken aback and put off. “Sheriff Grace thought I led you to that place?”

“I know, right? I hate cops.” She slouched down further. “He wondered if you had already found it, and were just trying to . . . what did he call it?” She screwed up her face in thought. “Were you trying to have me coronate your story, whatever that means.”

Coronate? Oh! “Corroborate?”

“Yeah, that’s it,” she said, her puzzled expression clearing. “Like, trick me into being the one who found the dead guy. But I told him no way. I told you about the camp, not the other way around.”

“I appreciate that. I’m new here, so no one knows what to think of me.”

“Yeah, you’re kind of different.”

The way she said it was a compliment. I think.

I told her about finding Becket and taking him to the vet, but I was thinking all the while. Would her mom ever tell her who her father had been, I wondered? Lizzie was owed the truth so she could at least have her aunt, Binny, to get to know. It would be good for Binny, too, I thought, since she appeared to have no one but her mother. But it wasn’t my place to interfere. Contrary to what some of my friends say, I do not think I know what’s best for everyone but myself.

After another half hour, Hannah trundled out the door and down the walk toward us. “Hey, there,” she said as she approached. “How are you girls doing?”

Lizzie, still a little shy with Hannah, ducked her head and said hello back. Hannah grabbed a book from the bag hanging off her wheelchair handle and gave it to the teenager. “I saved this for you,” she said.

The teen took the book and looked at the title, her face turning red.

I glanced at the cover. The book was entitled Uglies by Scott Westerfeld. I gaped at Hannah with horror, and she caught my look.

“What’s wrong?” she asked, glancing between me and Lizzie.

I glared at the title of the book and raised my eyebrows.

“Oh, my goodness, you don’t think . . . Lizzie,” she cried, stretching out her delicate hand. “I didn’t give you the book because of the title! Good lord . . . you’re a beautiful girl,” she said, wistfully stroking the teen’s hand. “I never even thought you could take it that way. I gave you the book because . . . because I wish it had been around when I was a teenager. It would have helped me understand how it’s good to be unique, and how no one should think they’re wrong for being different than her peers. You have a brain. You have a heart. That’s not always easy in this world, because they’ll try to stifle your smarts and crush your spirit.” Her chin went up. “I know that from experience.”

Lizzie smiled a crooked grin, then, and said she had to go, so she dashed off, book under her arm. I asked Hannah if she had another copy, because I knew I wanted to read it myself.

“I do. Come down to the library sometime and I’ll loan it to you. It’s a great book about thinking for yourself. Not something you’ve ever had a problem with, I’d bet.” After a pause, she glanced over at me, and said, “You do think it was okay that I gave her that book? Lizzie believed me, right? It never even occurred to me that she’d think the title was referring to her!”

“She believed you,” I said.

“I hope so. If she likes it, there are a couple more books in the trilogy.”

We were silent for another moment, each lost in our own thoughts. If there was anyone who would want to know about Lizzie’s paternity, it would be Hannah, who loved Tom so, but did I dare tell her? I didn’t know her well, despite our quick empathy. “Have you thought any more about the complications in Tom’s life, and who may have wanted him dead?” I asked.

“I have.” She folded her small hands together on her narrow lap and looked down at them, twisting a filigree silver ring around on one finger as she spoke. “Tom has not always been . . . circumspect. He’s made a lot of people angry.”

“Junior Bradley, for one.”

“Right, but others, too. I didn’t remember this until just yesterday, but he and Dinah Hooper had an argument one day in the middle of the street.”

“What about?”

“I don’t know,” she said, distress on her pretty, little face. “They were too far away, and there was no one around them.”

“Okay, anyone else?”

She glanced up and down the walk, and leaned toward me. “He . . . he had a big fight with Mr. Grover, the bank manager.”

“Really?” I thought about the genial Simon Grover, who had not seemed the type for a heated disagreement. I hadn’t seen him crossed, though. “Did you hear any of it?”

She nodded vigorously. “I didn’t remember until just yesterday—I’ve been so upset—but it was something about Turner Construction’s account at the bank, and Mr. Grover was telling him that it must have been a mistake on Tom’s part, because his bank didn’t make errors.”

That sounded kind of innocuous, and not like a fight that could lead to murder. She may have read that in my expression, because she shrugged. It was all she had. I considered something Pish had said to me, though, about the funny business with the accounts at Turner Construction; he had said it sounded like either drug peddling or a money-laundering scheme. I knew that some small businesses had made their revenue stream more robust by using their accounts to launder money.

So, was Tom involved in the funny business going on at Turner Construction? From my brief acquaintance with him, he seemed more the drug-peddling type than a money-scam guy, but there was no saying he hadn’t been doing both. Was he fiddling with the accounts in concert with Dinah Hooper? Or had he and his father been doing it behind her back, and she found out, but was trying to distance herself? Was Mr. Grover upbraiding Tom about the problems with the bank accounts? Confusing.

“Hannah, can I ask you a few questions about people you might know?”

She brightened. “Sure!”

I pondered for a moment. Where to start? Somewhere off the beaten path. “Do you know Lizzie’s mother?”

She turned pink and ducked her head. “Uh, I know of her. Tom knew her.”

How much did she know, or guess? “Did he . . . know her well?”

Hannah put her chin up and, soft gray eyes glittering, said, “Why don’t you come right out and ask, Merry? I don’t know for sure, but . . . but I think Lizzie might be Tom’s daughter. Is that what you’re fishing for?”

I was stunned into silence.

“She looks so much like him!” Hannah continued, a soft smile lifting her lips. “And even her expressions . . .” She trailed off and looked away.

I nodded. “Lizzie’s mom pretty much confirmed that yesterday when I took the kid back to her grandmother’s place. But Lizzie doesn’t know it yet. And I don’t think anyone ought to tell her until we know who killed Tom, at least.”

Hannah sighed and slumped a bit. “I’m glad,” she said. “A bit of Tom will still be in the world.” Her eyes welled, but she dashed the tears away with her finger, then fished around for a tissue, blotting her eyes. “What else do you want to know?”

“What does Isadore Openshaw have against Dinah Hooper?”

“What do you mean?”

I told her about Miss Openshaw’s anger toward the woman, expressed in the Vale Variety and Lunch.

“I don’t know,” Hannah said with a frown.

“Has Dinah ever done anything to her? Other than the catnip-mice incident at last year’s Autumn Vale Harvest Fair, I mean?”

“I don’t know Mrs. Hooper very well. She comes to Golden Acres sometimes. She used to have her son take people for walks . . . you know, push their wheelchair down the block and back.” Hannah chuckled. “That was no fun for Dinty, nor the resident!”

“Why not?”

“You had to know Dinty Hooper. He was a grumpy guy. When he finally took off, everyone in Autumn Vale heaved a sigh of relief.”

“You must talk to Miss Openshaw quite a lot, given all the books she borrows. What do you know about her?”

“Let’s see, she lives alone since her brother died, except for her cats. She works at the bank, pretty much the only teller other than a part-time girl who works on Fridays.”