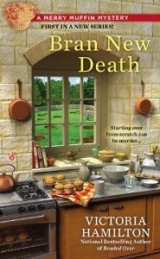

Текст книги "Bran New Death"

Автор книги: Victoria Hamilton

Жанры:

Женский детектив

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Chapter Six

I HATED TO say it, but had to. “Maybe that’s because it’s not murder.”

Gogi shrugged, an elegant insouciance in her manner. “I suppose no one will ever know, but I’ll always believe Melvyn’s death wasn’t an accident.”

There was no real answer to that, and we sat in awkward silence for a long minute. “I’m curious about Binny Turner, the owner of the bake shop,” I finally said as I got up to make a pot of tea. I was coffeed out, and needed my caffeine in a gentler form. “I get the impression she won’t make anything she deems ‘ordinary.’ What gives with that?”

“What are you talking about?” Shilo asked.

We both explained Binny Turner’s bake shop to Shilo, who said, “She made the focaccia we had for breakfast? Why doesn’t she just open a bakery in New York? I’d sure go there.” Shilo, like many models, loves to eat, and irritatingly does not gain an ounce. Superfast metabolism, she’s always said.

“She seems to have a mission to get the people of Autumn Vale to broaden their tastes.”

Gogi smiled and nodded. “Her dad put her through cooking school and she apprenticed for a year in Paris. But she’d get a lot more people in if she made some other goods, like muffins and peanut butter cookies.”

“She seemed pretty busy.”

“Only because she sells her wares for too little. If she sold them for what they were worth, no one would come in.”

“Hmm, you’re right there,” I agreed. “But costs must be a lot lower here than if she had a shop in Manhattan.”

“Maybe. She lived with her mom for most of her life, but after her dad offered to put her through school, they got closer.”

“And then he disappeared. Must be tough on her.”

Gogi shook her head, and said, “I feel for the girl, I really do.” She watched me get up and toss a tea bag into a saucepan, and said, “Merry, why don’t you open that housewarming gift I brought?”

“Okay,” I said, and retrieved it. I set it on the table and took the gorgeous, pink gauze bow off the large robin’s egg–blue box, then lifted the lid. There, nestled in pink tissue, was a teapot—and not just any teapot, but a real Brown Betty. I lifted it from the box and smiled.

Shilo stared at it, her forehead wrinkled in puzzlement, while Gogi watched.

“Thank you,” I said, not trusting the steadiness of my voice to say more.

“Do you like it?”

“I do. So much!”

“Do you know what it is?” she asked.

Shilo laughed out loud. “Who doesn’t know what a teapot is? Do you think we’re from the Antarctic or something?”

Gogi stifled a laugh while I shot my friend a look. “It’s a Brown Betty,” I answered. “It looks just like the one my grandmother used to make tea for all her Village cronies in our apartment in New York. Every Friday afternoon, her old friends would come around and they would have tea and ‘muffings,’ as I called them when I was little.” My vision blurred, and before I knew it I was sobbing, great wrenching, embarrassing sobs.

“Oh, no, what did I . . . is she okay?” I heard Gogi say.

“I don’t know,” Shilo said. “I’ve never seen her do this before, not even when her husband died!”

Two sets of arms were soon around me, and I just let it all go, the years of pent-up anguish that I had been holding onto even through my most recent tribulations, the accusations of theft leveled at me by someone I had once considered a friend. Stupid that a teapot finally broke my control, but that’s what happened. To my surprise I could feel and hear that the other two women were sniffling and sobbing, too.

After a minute, I blindly reached out and someone—probably Gogi, because Shilo was never prepared for anything—pressed a tissue into my hand. I dabbed my eyes, carefully pressing the tissue under them to staunch the flow of tears and keep the inevitable trails of mascara to a minimum, then blew my nose.

“Feel better?” Gogi said, her lovely pale eyes on mine. She smiled gently.

I could see no evidence that she had wept, and wondered if I was wrong after all. Shilo had tears still pooling in her eyes as she mournfully gazed over at me. I took a deep breath, cradled the Brown Betty in my arms, and said, “You know what? I do feel better.”

“I’m so glad you didn’t apologize for crying,” Gogi said. “I’ve always wondered why men think of crying as a weakness, when it is what helps women vent, then stand up and do what needs to be done. It’s a sign of strength, not weakness.”

“Then I must be a really strong woman,” Shilo said with a long sniff.

Gogi handed her another tissue, and my friend blew her nose. “So what happened to your grandmother’s Brown Betty?” the older woman asked.

“It broke the day she died. My mother dropped it while she was trying to make tea. I think she was stifling how awful she felt, and she was shaking from the effort. I didn’t know what to say; she just seemed to not want me to help, or comfort her, or anything.”

“I think it’s hard for a mother to let her kids see her cry,” Gogi said. “Virgil hates it, but he’s good about letting me do what I need to do.”

I knew she was likely referring to grief and pain during her battle with breast cancer, but didn’t say anything. If she wanted me to know, she’d tell me. I made tea in the lovely pot, poured for us all, and told Gogi about my teapot collection, and how I had felt a kinship for Binny the moment I saw her cool collection of teapots.

Shilo said. “You mean there is another woman in the world obsessed with teapots? And I thought you were the lone lunatic!”

I smiled. “Nope, there are a lot of us.”

“Merry, since you’re here for a while, I wonder if you’d consider doing something?”

I was wary immediately; Gogi Grace already had me agreeing to make 120 muffins a week, and that was about the limit of what could be expected from me, I would hope. “Uh, I don’t know. Do you need a kidney?”

Her eyes widened and she was startled into laughter. “No, I have very healthy parts, thank you very much, and the ones that weren’t healthy were lopped off.”

Again, I caught her wry reference to breast cancer, but I wouldn’t have understood it if McGill hadn’t already spilled the beans.

She drank the last gulp of her tea and stood. “I want you to think about something you could do while here. Since I can’t get my darling son to take me seriously, I wonder, would you sniff around and see if Melvyn’s death seems on the level to you?”

I was not expecting that and I laughed, thinking she was joking. She apparently wasn’t. I coughed, shrugged, and looked to Shilo for help.

But she was watching me, too, and said, “Maybe you should, Mer. I mean, he was your uncle, and he left you this big, beautiful castle! Poor guy . . . hey, maybe he could tell us what happened?”

I gave her an exasperated look. “Shi, really? Do you remember what happened the last time you tried to hold a séance?”

She had the good grace to look embarrassed. I turned to Gogi, who had a definite question in her eyes. “Shilo fancies herself a gypsy. We held a séance to contact my grandmother at Shi’s place. Shilo invited some friends, and the lights were out.”

Shilo snickered, and I threw her a dirty look.

“What happened?” Gogi said.

“My friend Gregory got fresh with Merry,” Shi said, giggling. “She decked him, and at the same time my bunny—his name is Magic—had gotten loose and hopped up onto the table, turned the candle over, and sent my neighbor shrieking out of the room and down to the superintendent to tell him my apartment was possessed.”

“And the candle set fire to the tablecloth and we had to put it out with the wine I’d brought,” I finished.

“But you had enough left to throw some in Gregory’s face,” Shi finished, still giggling.

“And your neighbor was really scared because you kept yelling ‘Magic! Magic!’ like a maniac, and she thought you were out of your gourd, when you were just yelling at your rabbit.”

Gogi Grace laughed heartily, but then finally said, with a sigh, “I have to get going. It’s getting toward supper, and some of the oldsters need help getting to the dining room. I’m always there at dinner.”

“I’ll bag these muffins for you,” I said. “And maybe pop them in a box; it might make them easier to carry. Four dozen muffins are kind of heavy. We’ll bring them out to the car for you.”

She graciously accepted our help, and Shilo and I followed her out to her car, parked by my rental in the weedy driveway. She put the muffins on the passenger seat and slammed the door. She surveyed the potholed land with her hand shading her eyes from the slanting sun, then her gaze settled on me. “You didn’t answer my question. Will you at least think about looking into Melvyn’s death?”

I felt uneasy, and I wasn’t sure why. An old man had died going off a slippery highway. There didn’t seem to be much of a mystery there, but then, Gogi Grace knew my uncle, and I didn’t. “Your son is professional law enforcement; if there was something there, I’d think he’d know.”

“He thinks I’m imagining things, but there were so many people who didn’t like Melvyn. And with his dealings with Rusty . . .” She shook her head. “The whole thing has upset me.”

“I’ll think about it.”

“Promise me you’ll really think about it, not just let some time lapse then say no.”

I shifted from one foot to another. She had certainly caught me at what I was planning. “I will seriously think about it, I promise,” I said, meeting her gaze.

She came around the car to me and enfolded me in a warm hug. “Thank you, Merry. And you, too, Shilo. You know, you’re right about Jack McGill,” she said, winking at my friend. “He is cute, and he’s a very smart fellow. A good catch!” She waved, popped into her car, and drove away.

As I watched her go, I had the troubling thought that maybe I would have to look into my uncle’s death. If it had anything to do with the Turners’ obsession with my property, and even, perhaps, their father’s disappearance, I might need to know so I could protect myself and my inheritance.

Chapter Seven

THE NEXT MORNING I left Shilo to “supervise” McGill’s hole filling. I was going to need to take back my rental car eventually, but not yet. Once I did, I would be relegated to borrowing Shilo’s rattletrap ancient vehicle, which I didn’t relish, or buying a car, which suited me even less, so for the next little while I’d stay with the rental.

I drove into Autumn Vale, intent on a few errands. Ingratiating myself to the locals was on my list, but first I was going to visit the lawyer. I had talked to Andrew Silvio many times over the last few months as he probated the will, but I had never met him. Gogi had given me directions to his office, and I found it with relatively little trouble. It was on the first floor of a beautiful, old house that had been converted to offices.

The central foyer, from which an impressive staircase wound up to a second floor, had a brass plate announcing whose offices were in the Autumn Vale Professional Suites. There was a doctor, a dentist, a chiropodist, and a licensed private investigator, among other professionals. I entered the glass door that had “Andrew Silvio” etched on it in gold, and as I did, a buzzer sounded somewhere close; a short, stocky man barreled out of an inner office. He looked around and saw me standing by the door.

“Miss Wynter, right?” he said, his voice gruff. “C’mon in. Nice day, huh? Take off your sweater. Want a coffee?”

I followed him into his inner sanctum, but didn’t take off my sweater. I slung my bag over the back of a chair and took a seat across the mahogany desk from him as he sat, donned close-up glasses, and shuffled through papers on his desk. “No coffee for me, Mr. Silvio. I came just to introduce myself in person, and ask for some advice.”

“Legal?” he asked, looking over the rims of his glasses at me.

“Not exactly.” I put both hands on the surface of the desk and composed my thoughts. Wow, I needed a manicure. That’s the first thought I had. Then I thought some more. “You knew my uncle.”

“I did. I was his legal representative in estate matters.”

“Why did he leave the castle to me?”

Silvio shrugged. “You’re his niece.”

“I know, but my mom had been estranged from him for well over thirty years. I’m just surprised that he still wanted me to have it.” I watched his face as his gaze shifted away.

He leaned back in his chair and plaited his fingers over his paunch. “One thing you may not know about Melvyn: the family name was important to him. He had me do research. He was pleased that despite your marriage, you kept the name Wynter.”

“But I didn’t. Not really. I took my husband’s name, but when he died I went back to Wynter.” I would have kept his name—I had loved being Mrs. Merry Paradiso—but I went back to my maiden name at the request of his family, who had never been fond of me. His mother blamed me for his staying in the States and dying here.

He shrugged. “Same thing.”

“If he had you do research on me, why didn’t he contact me? I don’t get it.”

The lawyer gazed at me for a long minute. “You know, death catches us all unaware, even an eighty-something-year-old man. I think he planned to contact you once he got a few things sorted out.”

“A few . . . what, like the lawsuits between him and Rusty Turner?”

“You’ve heard about that, huh?”

“Did you represent one of the men? Which one?”

“I was not able to represent either gentleman, since it would have been a conflict of interest in this particular case,” he said, threading his fingers together, the heavy ring on his wedding finger tripping up the action.

“Why?”

“I drew up the partnership papers, so it would have been deemed that I had special knowledge of Rusty’s business that would not necessarily be the case in the general run of things.”

“Who did my uncle use?”

“He retained a lawyer from Ridley Ridge, a very competent fellow . . . can’t recall his name right now.”

“Okay,” I said, disappointed. I had hoped for some information on the state of the lawsuits. Well, I had yet to go through my uncle’s papers; maybe I’d find more information there. “What was the nature of my uncle and Rusty Turner’s partnership?”

“Pretty simple, kind of an exploratory company to figure out if it was worthwhile to develop your uncle’s land for a condo neighborhood. That’s all I know,” he said firmly.

Given his desperate plans to try to monetize the Wynter estate, probably so he could keep the castle running, I wondered how Uncle Melvyn would feel about my plan to sell it. Nothing I could do about that, though. I couldn’t keep it. “I’m curious about Wynter Castle. If I’m going to sell it, it might help to write up a little history, you know, of anything important or interesting that happened there. Do you know anything about it?”

“Not a thing. I married into Autumn Vale; my wife is from around here, but I’m not. If you want to know more, maybe you should go to the library. The girl who runs it is a local.”

Now to broach a more delicate subject. “Mr. Silvio, I have heard some local talk that Melvyn was responsible for Rusty Turner’s death, or at least his disappearance.”

“Pfah!” he said, with a wave of one broad, ringed hand. “Gossip. People like to speculate, you know? Melvyn would never have done something like that.”

Okay, now for the even touchier part. “It has been suggested, too, that maybe Melvyn was murdered by the same person responsible for Mr. Turner’s disappearance.”

He sat up straight and glared at me across the desk. “Miss Wynter, I think you’ve been listening to a lot of small-town folk who are bored and find that speculating about murder makes their day more interesting. End of story. Poor old Melvyn was heading to Rochester. He told me he was going to go one day, and I told him to wait until the weather got better, but he was a stubborn old bird and his eyesight wasn’t so good.”

He could be right about bored locals speculating. Even Gogi Grace, as levelheaded as she seemed, could just be in it for the titillation. How much did I truly know about anyone in Autumn Vale? I stood and stuck my hand out. “Thank you for your time today, Mr. Silvio. May I come back if I have further questions about the estate?”

“Sure!” he said, reaching across and taking my hand. “Come back any time. I always like to see a pretty face.”

I smiled automatically at the intended compliment and showed myself to the door. I walked out of the house slash office building and looked up and down the street. I was just steps away from Abenaki Avenue, so I strolled toward it, getting my bearings as I went. Autumn Vale was indeed a “vale,” located in a valley between two rocky prominences. Maybe that was why cell phones did not seem to work, nor did the GPS in my rental.

Or maybe it was just that Autumn Vale is a truly weird little place. I stood at the corner of Abenaki and Wallace and watched the locals go by. There was an assortment of colorful individuals. One elderly fellow wearing an obvious yellowish wig came out of a variety store with a pack of cigarettes. He lifted the wig, balanced a few dollar bills on his bald pate, and plopped the toupee back down. Cool wallet.

I also recognized the old guy I had frightened the first morning in the village, when I mentioned Wynter Castle. He shuffled along, this time wearing a woman’s straw sun bonnet and a pink plaid sweater. I wondered if he was one of Gogi’s folks.

As I stood observing, I saw a big guy in a red-and-black-plaid jacket and unlaced boots strolling down the street. I was close enough that I had a good look at his face, and could see some long, angry-looking scratches from his temple down across his cheek. Interested in anyone showing such wounds, I sprinted to the sidewalk and followed him right up to Binny’s Bakery and inside.

“Binny!” he yelled, and hammered on the counter.

I turned my back and examined the wall of teapots as a group of elderly ladies, all bundled up in woolen coats and hats—overkill on a coolish but still mild September day, but then, I wasn’t eighty years old—entered and crowded around the pastry counter, oohing and aahing over the selection. Maybe Binny had something there about refining the locals’ palates, one pfeffernusse at a time.

The baker came out from the back, politely greeted the group of ladies, and then said, “Tom, do you have to yell and beat on the counter? What do you want?”

“Dinah left me a message; she said to tell you that she lost her key to the office, and could you lend her yours?”

“Why?” Binny asked. “She’s not even working there anymore.”

I half turned around and watched.

“Don’t ask me why she needs it. She just told me to get it.” He put out his hand, palm up, and waggling his fingers. “Hand it over!”

“No! Tell her she can ask me herself if it’s that important.” She turned to her customers and began to help them choose their treats.

The penny dropped and I got who this was. I said, “You’re Tom Turner!”

He looked me over, with a frown. He was a big enough fellow, dressed in stained work pants and dirt-encrusted boots. “Yeah, who are you?”

“Merry Wynter; I own Wynter Castle. Let me guess,” I said eyeing the long, red scratches down his face. “You got those lovely marks when you started up an excavator on my property to dig some more huge holes, and got attacked by a cat!”

His face got red enough to match the scratches and he loomed over me. “What are you talking about?”

“Tom, don’t talk to her!” Binny said, her voice shaking. She watched me, her dark eyes wide with fear. “Don’t say anything.”

“Why not? Afraid he’ll incriminate himself?” I said, trying to egg him on into a confession. “What are you guys looking for on my property? You don’t honestly think my ancient uncle Melvyn did away with your dad and buried him there?”

“You better shut up,” Tom bellowed.

The old ladies clustered together and watched, breathless, clutching each other’s arms in ghoulish delight.

“You going to make me?” I asked, in my best New York voice.

Binny had the phone in her hand and was dialing a number.

“I wouldn’t push me, if I was you, lady.”

“I’m not,” I said, backing down a bit and making my tone reasonable, as common sense prevailed. No real point in goading him to violence. I took a deep breath. “But I know for a fact that you’re the one damaging my property. I don’t know why you’re doing it, but I suggest you stop, now, or I’ll have you arrested for trespassing next time.”

“Tom, you keep your big mouth shut!” Binny warned, her hand over the phone receiver.

“Or just tell me the truth,” I said. “Why are you doing it?”

“You can’t prove nothing!” he said, his hands clenching into fists.

Only guilty people say that, and it made me mad. He was costing me a bunch, when all I wanted to do was sell the darned castle and scoot on back to New York. I got real close to him and looked up into his pouchy, red-veined eyes. Anger won out over common sense this time. “Look, you big goon,” I said, jabbing his chest with my pointed finger. “You come out to my property one more time and I will not be responsible for what happens!”

He sputtered and made inarticulate noises in the back of his throat, but nothing else.

“I’m calling the cops!” Binny said, watching us both.

“Good,” I said, moving toward the door. “Then I can tell Sheriff Grace exactly what I just told your brother, and he can look at those scratches.”

She slammed the phone down and glared at me, saying, “Maybe you had better go.”

Tom moved toward me slightly with a kind of growl in his throat, and I bolted outside. Heart pounding, I leaned against the brick wall. I hadn’t meant to get so worked up, but when I thought of how scared I was in the night, and how much it was going to cost to fix up the damage he was doing, I just lost it. When Tom stomped out the door, I don’t mind saying I hightailed it down the street, not wanting another confrontation. It was stupid to anger a guy who was that big and that short-tempered.

I strode down the sidewalk, heading who knew where, and dashed down a side street when I saw the sheriff’s car cruising toward the bakery. I didn’t know how to defend what I’d said, and didn’t want to deal with Virgil Grace at that moment. I walked along for a short way, leaving behind the clustered stores and buildings of downtown Autumn Vale, such as it was. I was fuming mad, at first, and didn’t much notice my surroundings, but the fog of fury began to dissipate.

I stopped and looked around; I was in a residential area now. The sign in front of me read Golden Acres. It was a lovely old manor, but didn’t look big enough to be a rest home until I started to walk up the angled drive. As I got past some of the century trees that shaded the grounds, I could see that a small, modern addition had been built behind the house. The drive sloped up to a prominence, where several park benches were set in the shade of a grove of maples along a smooth pathway. Some of Gogi Grace’s ‘oldsters’ were basking in the autumn sunshine, their faces turned upward like sunflowers, as the sound of warbling birds filled the air.

I nodded to them as I passed, and felt their eyes on me as I approached the door. I entered into a wide hallway, where a set of stairs ascended ahead of me and to the left. There was a reception desk, and the phone was ringing nonstop as the young woman who appeared to be the receptionist blocked the hallway.

“Mrs. Levitz, you can’t go out right now,” she said to an elderly woman. “It’s almost lunch. Don’t you want to stay and have lunch?”

The woman, wheeling along using a walker for support, had an angry look on her wrinkled face. She tried to dodge the girl, bellowing, “I’m going to see my mother. She’s waiting for me. School is over, and she always walks me home.”

“No, Mrs. Levitz, school’s not over yet,” the girl said, glancing to the left and right, probably looking for help.

“Yes, it is. You’re lying. If there’s anything I can’t abide, it’s a liar!” The woman plucked a stuffed animal out of the basket of her walker and chucked it. When the young girl dodged aside to pick it up out of the path of another resident, Mrs. Levitz rolled her walker around her and headed to the door.

I got in her way. “Ma’am, can you help me?”

The receptionist dashed behind her desk and hit a buzzer and another button. I could hear the lock on the front door snick into place.

“Who are you?” the old woman asked, glaring at me. “Are you one of the teachers?”

Just then, a big fellow in scrubs dashed down the hallway, and gently took Mrs. Levitz by the arm. “Dotty, your son is coming to see you this afternoon. Don’t you want to stay in? He’s going to come visit, and then he’ll take you for a long walk.” He gave the receptionist an apologetic shrug, and muttered, “She got away from Angie and we didn’t notice. Sorry, Jen.”

He got Mrs. Levitz turned around, confusion now wrinkling her brow as she plaintively asked, “I have a son?”

The receptionist swiftly answered the phone, transferred the caller, unlocked the door, and then smiled at me. “Thank you.”

“It was nothing,” I said. “Does she really think she was going to meet her mother? She must be about ninety!”

“Ninety-six and still hell on walker wheels,” the girl said and laughed. “Heavens . . . her son is over seventy! The dottiest ones are the most able to get about.”

She had a lilting Irish accent, and I smiled. “And Dotty is dotty, it seems.”

“Can I help you?” she asked.

“I was wondering if Gogi Grace is here?”

The receptionist hit a buzzer, and said, “Mrs. Grace, someone to see you. Your name?” She looked up at me.

“Merry Wynter,” I said and she repeated it.

My new friend, today dressed in a soft-purple suit with businesslike gray pumps and a purple paisley scarf draped around her neck, emerged from a door down the hall and beckoned to me. “Come along, Merry. I’ll give you the tour.”

The modern addition was small, but clean and bright, with bedrooms off a square, open area centered by a nurse’s station. There were two dining rooms, she told me, one for the mobile folk, and another for those who needed more room and more help. The second floor of the new section was much the same as the first; an elevator with wider-than-normal doorways and a deeper cabinet accommodated motorized wheelchairs, and could even be used for transporting patients who were bedridden. “Turner Construction, Rusty Turner’s company, did all the work on this seven years ago,” Gogi said.

“It turned out well!” I replied, impressed by the neat, simple layout.

She took me out a side door on the main floor and showed me the protected garden, cradled in the L shape between the modern addition and the old building. “Rusty did this a couple of years ago,” she said, pointing out the six-foot-high privacy fencing, safe even for those with dementia who might wander off, since there was no external access except a locked gate.

“So all of this is in the newly built area; what’s in the older section?” I asked.

“I’ll show you that now.”

I followed Gogi, who was talking as she went; upstairs in the old section were suites for those who could manage stairs and were more independent. We descended the wide, sweeping staircase, as she explained that on the main floor were the social rooms. She led me to what was probably once the dining room and parlor, linked by pocket doors, which were open. There were tables set up sporadically, and settees and shelves with books lined one wall. A few gentlemen and ladies were seated in some of the comfortable wing chairs near the fireplace and by the front window. Some were reading, others chatting, and one was just watching everyone else.

“We call this the library.”

A pudgy teenager with dark, frizzy hair pulled back in a tight ponytail carried in a tray laden with cups, sugar, milk, and spoons. She set it on the table in the corner. When she straightened, she noticed Gogi, and her sullen expression, mouth turned down in resentment, changed to one of uncertainty.

“Pardon me a moment,” Gogi said, then crossed the room and took her aside, speaking to her for a few minutes. The girl nodded, wiped away a tear, and nodded again. When they were done, the girl impulsively reached out and hugged Gogi. After that, her expression lighter, she went to each lady and gentleman in the room and offered tea or coffee.

“What was that all about?” I asked.

Gogi watched the girl for a long moment, then drew me aside. “I wouldn’t normally say anything; I try not to let people become prejudiced before they meet her, you know. She’s here on community service,” she murmured. She met my gaze, and answered the question in my eyes. “Graffiti. She was caught in the cemetery spray-painting awful slogans on gravestones.”

“Is this the right place for her?” I asked, a little shocked that they would put her with the elderly.

“Oh, I think so, with careful supervision, of course. In fact, I asked for her. I followed the case in the local paper, and when I learned that she had been abandoned by her mother and left in the care of her grandmother, who no longer could control her, I knew she was going to end up in a group home. I was afraid she’d never learn or understand why she was angry. She needs to figure that out if she’s going to get past it.”

I was silent for a long minute as I watched the girl caught by one old gentleman, who grabbed her arm and asked her something. She looked like she was ready to flee, but one look from Gogi kept her in place. She sat down, and before long the old man was talking to her intently, and she was listening. Truly listening; I could tell.

“That’s Hubert Dread. He has the most interesting stories. Not all of them are true, but they are interesting.”

“So, you think her graffiti problem was a result of . . .” I raised my eyebrows, a question in my tone.

“Fear. Anger. She was raging against living with an old woman who didn’t understand her, and yet at the same time she was afraid of losing her grandma.” Gogi sighed and shook her head. “That’s an oversimplification, and I don’t mean to play armchair psychiatrist, but it’s a beginning. She seems a little better already. It was a gamble; working here could have made her more angry, but it’s turning out the way I hoped.”

As Gogi led me to an alcove to sit, an old man wandered in, the one wearing the sunbonnet.