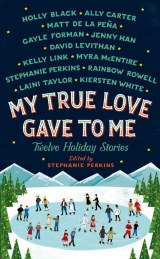

Текст книги "My True Love Gave to Me: Twelve Holiday Stories"

Автор книги: Stephanie Perkins

Жанр:

Рассказ

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

I didn’t tell anyone how dire shit had become.

Yeah, maybe my old man could slip a few bucks in an envelope, mail it to my Brooklyn apartment (where it might get carried off by a pack of gangster rats), but he had his own worries. He was saving up for my little sis’s summer camp. And our dog, Peanut—probably the most flea-bitten, bucktoothed crossbreed you could ever imagine—had just required an emergency dental extraction. I know, right? The dog with the busted grill has dental needs. Okay. But according to my sis, the procedure cost over three hundred bones, and they had to put my old man on some kind of payment plan.

It’s fine.

I’d just go hungry this holiday season.

Nothing to see here.

“Mijo,” he told me over the phone on my first full day of cat sitting. “Everything is good up at your college?”

I stuck Mike’s acoustic guitar back on its stand. “It’s all good, Pop.”

“That’s good,” he said.

This word good, I thought. How many times did he and I throw that shit around these days? My old man because he didn’t trust his English, me because I didn’t want him to think I was showing off.

“Next year we’ll get you a ticket so you could fly home for Christmas,” he said. “And me, you, and Sofe will be together as a family. How we belong.”

“Sounds good, Pop.”

He didn’t know it yet, but by next Christmas I planned to be living near home again, in southeast San Diego, taking classes at the local community college. Everyone seemed to think I had it made out here in New York—and on paper maybe I did. Full academic scholarship to NYU. Professors that blew my mind every time I sat in one of their lecture halls. But to understand why I planned to drop out after my freshman year you’d have to read the e-mails my sis had been sending. Some nights my pop—the toughest man I’ve ever known—cried himself to sleep. She could hear him through her bedroom wall. He wouldn’t eat dinner unless my sis physically dragged him to the table and sat him down in front of a plate of food. Point is, back home real-life shit was happening. Genuine mourning. And here I was, clear across the country, having the time of my life.

It would be impossible to describe the weight of that guilt.

There was a long, awkward pause between me and my old man—we’d yet to master the art of talking on the phone—before he cleared his throat and told me: “Okay, mijo. You will be safe from that storm. The news says it’s very, very bad.”

“I will, Pop,” I said. “Tell Sofe to stay away from dudes.”

We said our good-byes and hung up.

I slipped my cell back in my pocket and went to Mike’s cupboards for the two hundredth time. One multigrain hot dog bun and a few stray packets of catsup. That was it. The stainless steel fridge wasn’t any better. An unopened dark chocolate bar, a half-full bag of baby carrots, two plain yogurts, and a bottle of high-end vodka. How could such a beautiful apartment contain so little food? My stomach grumbled as I stared at the beautiful yogurt cartons. But I had to conserve. It was still three days before Christmas, and I wouldn’t see a dime until the day after that.

My manager at the campus bookstore, Mike, and his wife, Janice, were paying me to cat sit at their brand-new apartment—which was about three hundred times nicer than the broken-down room I rented in Bushwick—but Mike forgot to hit the ATM before he left and asked if he could pay me when they got back from Florida.

No problem, I lied.

To make matters worse, a few hours after they left, a record-setting blizzard sucker punched New York City, blanketing Mike’s Park Slope neighborhood in thirteen inches of angry-ass snow. Translation: even if I wanted to dust off the survival skills I’d picked up back home (how to mug somebody), I couldn’t. Everyone was waiting shit out in the warmth of their cozy apartments.

I closed the fridge and went into the living room and stared out the front window, next to the cat—Olive, I think Mike said her name was. My empty stomach clenched and twisted and slowly let go, then clenched again. The few remaining cars parked along the street were buried under snow, and it was still falling. The trees that framed my view all sagged under the weight of the stuff.

I turned to Mike’s cat, said, “I promise not to eat you.”

She looked at me, unimpressed, then hopped down onto the hardwood and sauntered off toward the kitchen, where a heaping bowl of salmon-flavored dry food awaited her.

Faulty Plumbing

I was a quarter of the way through one of Mike’s precious yogurts when there was a knock at the door. I froze, my spoon halfway between my mouth and the plastic carton. Who could that be? You could only enter the building if you got buzzed in, and Mike told me I was the only one in the entire seven-story complex who hadn’t traveled anywhere for Christmas.

More knocking.

Louder this time.

I stashed the yogurt back in the fridge, went to the door, and looked through the peephole. A pretty white girl was standing on the other side—long sandy-blond hair and porcelain skin and light brown eyes. I was still getting used to being around people like this. The kind you see in movies and commercials and sitcoms. Back home everyone you passed on the street was just regular-old Mexican, like me.

I undid the chain and pulled open the door and tried to play it cool. “Can I help you?”

“Oh,” she said with a look of disappointment. “You’re not Mike.”

“Yeah, we work together at—”

“And you’re definitely not Janice.” She looked past me, into the apartment.

“Mike’s my boss,” I said a little too quickly—definitely not cool. “I’m cat sitting while he and Janice are in Florida visiting friends. He totally knows I’m here.” My heart picked up its pace. I didn’t need this sitcom girl thinking she’d stumbled into an active crime scene. I pointed into the apartment, but Mike’s cat—my lone alibi—was nowhere to be found. “I’d be happy to pass along a message. They’ll be back the day after Christmas.”

“Do you know anything about pipes?” she asked.

“Pipes?”

“Pipes.” She paused, waiting for a look of recognition from me that never came. “Like, sinks and showers and … you know, pipes.”

“Oh, plumbing.” I didn’t know the first thing about plumbing, but that didn’t stop me from nodding. When it comes to attractive females my policy has always been to nod first and ask questions later. “Sure. Why, what seems to be the problem?”

The cat strolled out from its hiding place and rubbed itself against my leg. “Awww,” the girl cooed, kneeling down to scratch behind its ear. “She likes you.”

Mental note: Give Mike’s cat extra food before bed. It’s impossible to look like a criminal when there’s a well-groomed calico rubbing against your calf.

“Yeah, we’ve really hit it off these last twenty-four hours,” I said. “I’m already dreading our good-byes.”

“You’re a little cutie, aren’t you?” she said in that strange voice girls reserve for animals and small children. I watched her scratch down by the cat’s tail. She was wearing an old, beat-up sweatshirt, ripped jeans, and Ugg boots, but I could still tell she came from money. This gave her a certain power over me that I was nowhere near schooled enough to understand.

She stood back up, and when our eyes met this time, my stomach growled so loudly I had to cover it up by faking a small coughing fit.

“You okay?” she asked.

I straightened up, nodding. “Yeah. Wow. Excuse me.”

“Anyway,” she said. “I have a little situation upstairs. When I try and turn on the water in the shower, nothing comes out. Like, not even a drizzle. Do you know about stuff like that?”

“A little bit.” Lies! “Need me to take a look?”

“Would you?”

“Lemme grab the keys.” I darted back into Mike’s living room trying to call back all the times I’d seen my old man go at the plumbing underneath the kitchen sink with his trusted wrench. I could still picture him lying on his back, halfway in the cabinet, twisting and turning things in a chorus of clanging metal.

Why hadn’t I paid more attention?

Fake Espinoza

Her place smelled like tomato sauce and garlic bread and Parmesan cheese. As she led me through the kitchen, into the long hall, my mouth started watering its ass off. Maybe I was better off staying in Mike’s pad, where I’d been able to convince myself that the entire borough of Brooklyn was participating in a Christmas fast.

“I’m Haley, by the way.”

“Shy,” I told her.

She glanced at me, still walking. “Like, S-H-Y?”

“Exactly.” I’d been through this exchange dozens of times since landing in New York. Which I found strange. Nobody back home even thought twice about my name.

Haley shrugged and we shook hands awkwardly on the move, and then she stopped in front of the bathroom door and motioned me inside. “This is it. It’s the same thing with my roommate’s shower, too.”

Her bathroom smelled of perfumed soaps, and there was a framed poster of a couple kissing in front of the Eiffel Tower. Her sink was covered with makeup and eyelash curlers and this fancy circular vanity mirror that made my face look three times its normal size. There were pastel-colored towels in two sizes stacked neatly beside the black polka-dot shower curtain, which Haley swept aside. She turned both valves all the way on, but nothing came out. “See?” she said.

“Interesting,” I told her, staring at the faucet and rubbing my chin. I turned on the Hot valve again, then the Cold. They didn’t work for me, either. Then I ducked my head under the bath spout and stared up into the matchbook-sized hole, pretending to be studying God knows what.

I knew my old man was proud of me in certain ways. When NYU called from across the country offering to pay my entire tuition—as well as a monthly stipend for living expenses—he even threw a party to celebrate. My aunties, uncles, a few cousins, and my girl at the time, Jessica, all came over with home-cooked dishes and booze, and just before we sat down to eat, Pops held up his can of Tecate to say a few words (in English out of respect for Jessica). “I never believe this was possible,” he said, looking around our small living room. “A college boy is an Espinoza. But it happens. Congratulations to my son, Shy!” Everybody clinked glasses and drank and patted me on the back and told me they always knew I would do something special.

But at the same time, all of us were aware that I’d failed to learn the one thing that defined Espinoza men: the ability to work with one’s hands. Pops had tried to show me how to change the oil in his truck, how to strip shingles off an angled roof and lay hot tar, how to rewire a dead outlet, but it didn’t take long for him to realize I was a lost cause. My one talent in life? Filling in those little bubbles on Scantron sheets. That was it. Honest to God, I had a gift for those damn bubbles.

“I wonder if it has something to do with this weather,” Haley said, as I continued turning the valves back and forth. “Like, maybe the pipes froze.”

“I was just thinking that.” I looked up at her. “It would explain the lack of water pressure.” I had no idea what I was going to say next until I said it.

“Great,” she said, sarcastically. “My shower doesn’t work, and the super’s upstate until after the holidays. I guess I’ll be growing some holiday dreadlocks.”

“Seems weird the pipes would freeze in a brand-new building,” I said.

“Right? And why does the toilet still flush?” Haley pushed down the silver handle to prove it, and we both watched the water swirl and suck down the bowl in a gurgling crescendo before slowly rising again. “Maybe they’re on different lines or something?”

“They’re definitely on different lines,” I said, because it sounded pretty logical. Plus, I would hate to think my shitter was connected to the faucet I used to brush my teeth.

“The kitchen sink works,” Haley said, “but not this one.” She turned those two valves as well and nothing came out. She shook her head. “I should be back home in Portland right now, standing under a scalding-hot shower. But like an idiot I waited until the last minute to book my ticket. And then, you know, they canceled all those flights.”

“You’re welcome to use Mike’s shower,” I said.

Haley looked at me for a few long seconds, like she was thinking. “That’s sweet, but I’ll be all right. Isn’t it supposed to be good for your skin to occasionally skip showers?”

“I’ve heard about that.” But I knew the real reason. I didn’t strike her as the trustworthy type. I was wearing ripped jeans and an ancient-looking T-shirt. I had my home area code tattooed clumsily onto my knuckles on both hands.

Don’t ask.

I was only fifteen and tequila was involved.

“Something about the natural oils or whatever.” She shrugged. “Anyway.”

I turned back to Haley, who was obviously waiting for me to leave now that I’d proven useless. “Well, I should probably get back downstairs to feed the cat. Sorry I couldn’t help.”

“No worries.” She led me out of the bathroom and back through the hall and kitchen, where my empty stomach sounded like the Fourth of July.

She held open the front door.

“Happy holidays,” I told her.

“You too.” She smiled. “And I appreciate you coming up here to take a look.”

As I walked toward the elevator, I listened for the click of Haley’s door behind me. When I finally heard it, I felt crushingly alone.

How to Pass a Night

I finished the plain yogurt for dinner along with half a hot dog bun, then I broke into Mike’s vodka. I sipped a few glasses over ice while strumming the guitar in the bathroom—my favorite place to play because of the acoustics. Mike’s guitar was about six thousand times better than mine. It was like playing a stick of butter. Basic open chords came alive inside the tiled walls, especially after I flipped off the lights.

Once the vodka kicked in, I even sang a few of the tiny songs I’d been making up since high school—melancholy tunes about females and back home and losing my mom. Tunes made out of minor chords, where my pedestrian voice was no more than a whisper.

This was where music had always existed for me.

Inside a dark bathroom.

Alone.

The feeling it gave me was an odd combination of weightless self-pity and excitement. I understood my life was meaningless, and this knowledge freed me up to accomplish absolutely anything.

Anyway, I passed most of the night this way.

The cat came into the bathroom a few times to check me out. And whenever I’d hear Haley’s subtle footfalls—her place was directly above Mike’s—I would stop singing and strum more softly.

Around midnight, I put away the guitar and pulled out the book I was reading and moved into the living room, and it wasn’t long until I found the cat curled up next to my feet. I guess we were becoming actual friends. Something like that. I leaned over to read the charm hanging from her collar: Olive.

Mike had told me her name when he showed me how to do the food and change the litter, but this felt like our true introduction.

I scratched behind Olive’s ear the way Haley had and listened to the ceiling, but it had gone quiet up there.

Long-Distance Relationships

Late the next afternoon, there was another knock at the door.

I turned away from the window, where Olive and I had been sitting together, staring at the perpetually falling snow. I kicked the blanket off my feet and went to the door and looked through the peephole. Haley again. This time she’d brought with her a towel, a change of clothes, and a bathroom bag. I opened the door, saying, “You changed your mind.”

She peered into the living room. “Your TV’s not on.”

“Uh … yeah.” I looked over my shoulder, at Mike’s dormant big screen. “I mean, no. Wait, why?”

“What do you do in here all day?”

“I cat sit.”

Haley rolled her eyes. “Most cat sitters can manage to watch TV at the same time.” She switched her bathroom bag from one arm to the other, adding: “Not sure you’re aware of this, but we’re kind of snowed in right now, which is the perfect excuse to stream Netflix. I watched an entire season of Downton Abbey yesterday.”

“Is that the one about those rich British people?”

“I’m pretty sure your TV feed didn’t go the way of my shower pipes,” Haley said, ignoring my question.

I pointed to her bathroom bag. “I see you reconsidered the Christmas dreads.”

She let out a dramatic sigh. “I thought about it last night. And I’m going to take you up on your offer.”

I sensed a but coming.

“But here’s my thing.…” Haley glanced around Mike’s apartment. “Interesting,” she said, distracted. “It’s the exact same layout as my place, but at the same time it looks totally different.” She turned back to me. “In order for me to feel comfortable taking a shower down here, we have to both share something about ourselves first. Then I’ll feel like I know you better. And it won’t be so weird.”

“Seriously, Haley. I’ll stay way on this side of the apartment. I promise.”

“That’s not the point.”

I glanced into the kitchen where Olive had gone back to housing her wet food. My empty stomach was beyond the cramping stage now, which made me wonder if I’d started digesting muscle. I stepped aside, motioning for Haley to come in.

She walked over to Mike’s L-shaped couch and sat down.

I sat, too. “So, what kind of stuff are we supposed to say?”

“Anything,” she said. “It could be about your childhood. Or about where you’re from. Or why you’re wearing a beanie indoors. Seriously, anything.”

I pulled off my beanie and opened my mouth to ask a follow-up question, but she cut me off. “On second thought, maybe you should put that back on.”

“Why?” I stood up to look in the mirror mounted on the wall behind the couch. My hair was a rats’ nest of thick, brown waves. It was the longest I’d ever had it. I put the beanie back on, saying: “I guess I kind of need a haircut.”

“You think?”

Sweet, another thing I couldn’t afford.

Back home my auntie Cecilia always cut it for free.

“Okay, I’ll start.” Haley paused for a few seconds, looking around, then said, “Long-distance relationships are all about patience. And my boyfriend, Justin, is probably the most patient man alive.”

“How so?” I took the bait, even though I knew what she was doing. This was Haley’s way of establishing that she was in a relationship, which she believed would lessen the risk of me trying to sneak into the shower with her while she was busy rinsing out her Awapuhi.

“Like I said yesterday,” Haley answered. “I was supposed to book my own ticket home. But I procrastinated. So Justin’s back in Portland right now, hanging out at home, when we were supposed to be heading to a B&B in Seaside. Our parents are friends, and they said as long as we were back by Christmas day.… Anyway, instead of getting mad at me, which is what I would’ve done, all Justin wants to talk about is my frozen pipes. He actually feels bad for me, can you believe it? That’s some serious patience.”

“Wow,” I said, playing along. “He sounds … patient.”

“Okay, now you.”

I sat there for an uncomfortable amount of time, trying to think of something interesting to say. I couldn’t talk about a distant girlfriend the way I wanted to—which would definitely make Haley feel more comfortable about the shower situation.

“It doesn’t have to be some big profound thing,” she told me. “It can be simple.”

“Got it,” I said, still brainstorming. Then it came to me. “My little sister, who’s probably my best friend in the world, turns seventeen on Christmas day. This is the first birthday of hers I’ll have ever missed.” Sofe wasn’t technically my best friend, and she didn’t technically turn seventeen until the week after Christmas, but the point was to show Haley I was a solid brother, which would hopefully increase her trust in me.

“Ah, that’s sad. Why didn’t you go home?”

No money! “Because I promised Mike I’d cat sit.”

Haley frowned. “I’m sure he’d have understood. It’s Christmas. And your sister’s birthday.”

“I have a lot of homework and stuff, too,” I lied.

“Ah, I figured you were a student,” Haley said. “What school?”

“NYU.”

She nodded. “Isn’t your semester over?”

I pulled my beanie tighter over my forehead and shifted positions on the couch. “Actually, it’s for next semester.” I pointed at the novel I’d been reading. “This one lit class I’m taking has a grip of reading. I’m trying to, like, get ahead, you know?” It was true that a class I’d signed up for had a large reading list, but the book on the couch had nothing to do with school. And I was a fast reader.

“What year are you?” Haley asked.

“Freshman. You?”

“I’m a sophomore at Columbia.”

“Nice, a college veteran,” I said.

Haley forced a laugh. “Please. I have no idea what I’m even going to major in.”

I glanced at my book again.

There was another awkward silence at that point, and after a few seconds Haley stood up and said, “See?”

I stood up, too. “See what?”

“Now we know a little about each other. Which means it’s less weird for me to take a shower at your place.”

“Well, technically,” I pointed out, “it’s not my place.”

“It’s yours through the holidays, right?”

“I guess so.” I watched Haley disappear into the hall, and a few seconds later I heard the bathroom door in the master bedroom close. I looked around the apartment, trying to imagine it as my place. The designer couch. The expensive-looking leather chair. The massive flat-screen mounted on the wall. The fancy-looking paintings.

What would my old man say if he saw me standing here right now?

He’d think I was cat sitting in a museum.

I read the entire time Haley was in Mike’s bathroom—which was a shockingly long time. When she finally walked back into the living room, her hair was wet and I could tell she was wearing fresh makeup. She looked beautiful.

I sat down my book and got up, saying, “Everything go okay in there?”

“It was quite lovely. Thanks.” She waited for me to open the front door. When I did, she looked me dead in the eye and said, “Thank you, Shy.”

I got a weird, unbalanced feeling hearing her say my name, and I told her, “My shower’s your shower, Haley.” But that sounded kind of sexual so I quickly added: “I mean, you can bathe in my place anytime.” But that was creepy, too. “I mean—”

“I know what you mean,” she said, saving me from myself. “I appreciate it.”

She gave me a nice smile and left Mike’s apartment.

When I closed the door, I found Olive looking up at me, accusatorily.

“What?” I asked.

She meowed.

“Look,” I told her, “you’re gonna have to start speaking English around here.”

She stuck out her front paws, stretched her multicolored back, and crept away.

Angels in the Snow

Haley was back early the next morning with her bathroom bag, a change of clothes, and a fresh towel. “I don’t mean to keep interrupting … whatever it is you do down here,” she said, “but I kind of had an accident in the kitchen.” She held out the front of her gray Columbia sweatshirt. There was a large catsup stain between the m and the b.

I motioned for her to come inside. “You can just leave your stuff in there if you want.”

She forced a laugh. “Yeah, I don’t think so. That would be taking it way too far. Besides, how do I know you’re not the kind of person who snoops through people’s things?”

“I don’t even shower in there. I use the one in the spare bedroom.”

“That’s what they all say.” She looked down at her catsup stain again. “I know technically this is more of a laundry issue, but I feel dirty.”

“Like I said, you can shower down here whenever you want.”

She set her stuff on the dining room table and reached down to pet the cat. “You’re a friendly one, aren’t you girl? Oh, yes, you are.”

“Her name’s Olive,” I said.

Haley looked up at me. “We’re on a first-name basis now, I see.”

I shrugged. For some reason I wasn’t feeling like my usual laid-back self. I think the hunger was making me irritable. But at the same time, I was happy to be talking to Haley again. Being hungry is bad news. Being hungry and alone? That’s when people start Googling info about suicide hotlines.

She stood up and put her hands on her hips, like she was waiting for something. That unbalanced feeling I got whenever we made eye contact was no longer confined to my stomach. It had moved up into my chest.

“What?” I said.

“You go first this time,” she said.

“We’re doing that getting-to-know-you thing again?”

“Yep,” Haley said. “Every time I come down here, we have to share one new thing. Those are the rules. And ideally it should be something highly personal. The last thing you shared was kind of boring—no offense to your sister.” She glanced over my shoulder, into Mike and Janice’s kitchen. “What are you doing for meals? It never smells like you’ve cooked anything, and I usually hear the takeout guys when they’re coming up the steps.”

“Oh, Mike left a stocked fridge for me,” I lied. “The cupboards are all full, too. They made this big grocery-store run to the new Whole Foods before they left and said I should eat as much as I can.”

“Nice,” Haley said. “But I’m guessing you don’t actually cook.”

I shook my head. “I mostly make sandwiches. And cereal. Easy stuff like that.” My stomach cramped so aggressively at the thought of these mythical meals I winced in pain.

“You’re welcome to eat with me. It’s just as easy to cook for two as it is for one.”

For reasons I didn’t fully understand, Haley’s offer made me want to cry.

I broke eye contact and kneeled down to pet Olive. I was so hungry now I constantly felt lightheaded. My arms and legs felt like Styrofoam. I’d finished off the hot dog bun and baby carrots and the yogurts the night before. When I awoke in the morning, I had half of the chocolate bar. I still felt hungry, though, and drank glass after glass of tap water thinking it would fill me up. It didn’t work.

“Well?” Haley said. “Do you want to come up and have dinner tonight? I was thinking of making vegetable lasagna, my mom’s special holiday recipe.”

My mouth started watering.

Real food.

“I can’t,” I told her.

“What do you mean you can’t?”

I didn’t know how to answer this truthfully. Maybe it was stupid pride—the one thing I had picked up from the rest of the Espinoza men. Or maybe it was a fear of being found out. I constantly felt like an imposter among the other students at NYU. When were they going to figure out I didn’t belong here, that some lady in admissions had made a mistake, had offered a scholarship to the wrong guy? I probably spent as much time trying to hide my ghetto as I did on homework.

“I’m supposed to talk to my family back home,” I said.

“Then come up after.”

“No, like my whole family,” I told her. “Since I won’t be there on Christmas. But I totally appreciate the offer.”

She just stared at me for a few long seconds. “You’re weird.”

I guess she had that part right.

“Anyway.” Haley grabbed her stuff off the table. “You go first this time.”

I still felt oddly emotional, which wasn’t like me. In fact, I hadn’t cried for over a year, since my mom’s funeral.

Maybe that’s what I could tell her, I thought. How when I saw my mom lying in the casket, my dumb ass broke down … in front of everyone. How I started shouting about the world being a fucked-up piece-of-shit place that I was done with, too. How a few relatives tried to get me to calm down, but all I did was turn my wrath on them. “Who you talking to?” I shouted in my uncle Guillermo’s face. “You don’t know shit about me!” When he reached for my arm I smacked his hand away. I could tell Haley about that. How tears were streaming down my face, even though my expression never changed, not even a little. And I kept shouting, “I don’t give a fuck about anything! You hear me?”

I didn’t stop crying until my dad came over and slapped me across the face. Right there, in front of everyone. At the foot of my mom’s casket. Slapped me like I was some punk five-year-old.

And as I walked out of the funeral home that day I made myself a promise.

I would never cry again.

For as long as I lived.

No matter what happened or who got sick and died.

“Hel-lo.” Haley waved her hands in front of my face. “Earth to Shy.”

I took a deep breath and let it out slow. Instead of telling her about my dead mom, I told her about the first time I saw snow.

Two years ago, our family drove to the mountains outside of San Diego and stayed at a campsite, in a family-sized tent my uncle loaned us. My parents promised me and my little sis we’d see snow, but the first three days there was nothing. It was just cold. And windy. We spent the majority of our time inside the tent, playing stupid games like Uno and Loteria and Mexican dominos. But when we woke up on the morning on the fourth day, it happened. Thick beautiful snowflakes were falling from the sky. And it had accumulated on the ground all around us. I told Haley how while my dad and sis took turns going down this little hill near our campsite on a cheap plastic sled, me and my mom lay on our backs and did snow angels just outside our tent. Like a couple of giggling kindergartners. And when we got up to check them out, it looked like our angels were holding hands.

Haley smiled. “You’re getting better at this.”

I shrugged, still picturing the life I used to have.

“Isn’t it funny how one day you’ll be hoping for something, like snow, and the next day you’ll be hoping it goes away?” Haley motioned toward Mike’s big windows, where the snow was still coming down.

We watched it for a while, then Haley told me about the time she first became aware of race. She didn’t know why, but last night, the memory came to her out of nowhere. Maybe because of something she was watching on TV. Anyway, she was a little girl living in a wealthy suburb outside of Portland. And for her sixth birthday, her parents took her into the city to see a musical. They made a big thing of it, got dressed up and everything, hopped in her dad’s Mercedes and made the drive. Haley said she remembered driving by this one McDonald’s, in a sketchy part of the city, where she saw a group of black women dressed strangely, wearing tons of makeup—they were prostitutes, though she was too young to understand that. Haley was in the backseat, in her fancy white dress, staring at these women, because she’d never seen anything like it. Her dad stopped at a light right in front of them, and while he waited for it to change, Haley stared and stared, until one of the women turned and met eyes with her. But Haley still couldn’t look away. She was transfixed. After a few seconds, the woman wobbled right up to Haley’s window, in her sparkly high heels, and pointed a finger in Haley’s face. “Wha’chu staring at, white girl? You trying to steal my story?”