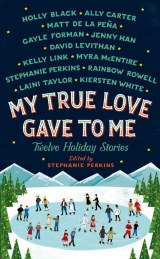

Текст книги "My True Love Gave to Me: Twelve Holiday Stories"

Автор книги: Stephanie Perkins

Жанр:

Рассказ

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“Aren’t you going home for the holidays?”

“I’ll be home for Christmas and New Years but no, not Hanukkah this year.”

“Why not?”

Sophie paused, wondering which way to answer that. “Two hundred and sixty-seven dollars,” she said finally.

She told him that this was how much the price of tickets dropped if she left next week. Sophie had fought with her mother about this, which was unusual. She was accustomed to frugality. It had always been that way, a matter of necessity with just the two of them and her mother’s slender income. But also because any surplus had gone to Sophie’s college fund. Then last winter, right as Sophie was filling out her applications, Luba had a stroke. She’d lingered in a sort of twilight and neither Sophie nor her mother could bear to put her in one of those public nursing homes (they were so Soviet). When she died, five months later, Sophie’s college savings was history. NYU had said yes, but Sophie’s dream school was suddenly exorbitant, even with a financial aid package. Then U of B came along with its generous offer.

Sophie’s mom hadn’t been able to fly her home for Thanksgiving. And now, this latest postponement. These were the first holidays with Luba gone. Sophie wondered if that wasn’t the real reason for the delay. Maybe her mom wanted to skip the holidays this year. Maybe Sophie did, too.

Thinking about all this, Sophie started to cry. Oh, for Christ’s sake. This most certainly qualified as a What the Hell Have You Done, Sophie Roth? moment.

“You okay?” Russell asked.

“Holiday stuff,” Sophie said, wiping her nose. “I don’t even know why I’m crying. Hanukkah’s lame. Who cares if I miss it?”

Russell was looking at her. Curiously. Softly. Knowingly.

“Who says you’re missing it?”

* * *

Since they’d started this Hanukkah thing, Sophie and Russell decided to see it through, by lighting the menorah she had buried somewhere in her closet. It was Luba’s. The last time they’d used it was a year ago, just before the stroke. Hanukkah had come crazy early, colliding with Thanksgiving, so they’d had a huge feast: turkey and brisket and latkes and potatoes and donuts and pie for desert. But Sophie could only allow herself to think about that for a second. Summoning those memories was like touching a burning pot. She could do it only briefly before she had to pull away.

As they drove back to campus, Sophie realized that though she had a menorah, she didn’t have candles. They drove to the grocery store on the outskirts of town. It was empty, the aisles small, the floors dingy and scuffed. Russell pushed Sophie around in a rickety cart as the tired stock boys watched them warily. Sophie whooped with laughter. Grocery-cart derby. Who knew that would make such an excellent dating activity? (And by now, she was pretty sure this was a date.)

The candle selection was unsurprisingly pathetic. A whole shelf of plug-ins, an odd assortment of birthday numbers (4 and 7 were disproportionately represented) and some glass emergency candles, meant for blackouts and other catastrophes. Nothing that would remotely fit a menorah.

Russell had his phone out, searching for stores that would be open this late. But Sophie was already reaching for the emergency candles. “This holiday is about being adaptable,” she said. “My people are notoriously scrappy.”

“I can see that,” Russell said. “So how many we need?”

“Nine,” said Sophie. “Eight for the eight nights of Hanukah, plus an extra lighter candle. If we’re being official about it.”

There were nine emergency candles on the shelf.

“Wow,” said Sophie. “That’s almost like the actual Hanukkah miracle.” She explained the origins of the holiday, the oil in the menorah that should’ve lasted a single night lasting eight. “It’s really only a minor miracle,” she added.

Russell looked at her and cocked his head. “Not sure there is such a thing as a minor miracle.”

* * *

They drove from the store back to campus. Let It Bleed was still playing, and they put “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” on again. This time, Sophie sang along, quietly at first, then belting the words. If she was off-key, she didn’t care.

* * *

Back on campus, after Russell parked his car, they walked through the quad toward Sophie’s dorm. It was empty now, no sign of the reindeer orgy they’d escaped. That all felt like a million years ago.

“Why’d you talk to me earlier?” Sophie asked. “Was it really because of Ned Flanders?”

“Partly,” Russell said, stretching the word out in a way that made Sophie want to scratch it.

“What’s the other part?”

“You don’t remember me then?”

Remember him? She would if there was a reason to. She was sure of it. Except he was looking at her like they had a history.

“Poetry Survey.”

Sophie had only been in that class for a week. She’d hated it so much. It wasn’t even taught by a professor, but a TA with a nasal twang who had insisted on very specific interpretations of the poems. She and Sophie had gotten into it about the Yeats poem “When You Are Old.” It was yet another What the Hell Have You Done, Sophie Roth? moment, a big one. One that made her question coming here.

“I regretted not going to bat for you when you had your … disagreement.”

Disagreement. More like a war of words. She and the TA had debated about one line from the poem—“How many loved your moments of glad grace”—and Sophie had found herself on the verge of tears. She’d had to leave the hall before the period ended. She’d dropped the class the next day.

“If it makes you feel better, after that, a bunch of us started challenging her,” Russell said. “‘Poetry isn’t math’ was our battle cry.”

It was what Sophie had said to the TA. A sort of retroactive relief—or maybe vindication?—crept over her. She’d had defenders in that class. Wingmen. Even if she hadn’t noticed them. Hadn’t noticed him. The truth was, she didn’t notice a lot of things at school. She kept her head down, wore blinders. It was a survival tactic. Only now did she wonder if it was a stupid survival tactic, like wearing a life jacket made of lead.

“I asked about you, after the class. Got some intel, about you being big city and all,” he said with a teasing smile. “But I never spotted you for more than a blur. Until tonight … I was debating saying something. You were looking pretty fierce, not fit for company.” He grinned again, but it was different, less oozy, more shy, and about a thousand times sexier. “But then you mentioned Ned Flanders, and I had to say something.”

“What? Is Ned like your spirit guide?”

He laughed. That big, open-chested laugh. “We lived all over, sometimes moving every year. All the places I lived, The Simpsons was like this one constant. They had it everywhere, sometimes it’d be English, sometimes dubbed, didn’t matter. It was my comfort food.”

“You make it sound sad,” Sophie said. “Living all those places sounds pretty great to me.”

“Things are not always how they seem.”

The look they exchanged was like a road map of the history they’d already traversed tonight. “So what was it really like?” Sophie asked.

“Ever see that movie Lost In Translation?” Sophie nodded. She loved that film. “Like that, over and over. But times a thousand because I’m black in places where they just don’t get black. In Korea, they called me Obama.” He sighed. “Before Obama’s presidency, I was Michael Jordan.”

“Is that why you came to school here?” Sophie asked. “Because you knew what to expect?”

Russell looked at her a while before answering. “Yeah. Some of that. Also, to piss off my parents. They thought I was crazy for coming here, but I thought I was making a grand statement. Like, hey, this is how it’s always been for me so I’m just going to go back for more.” He laughed, a little sadder this time. “Only problem is, they never got that and even if they did, being here isn’t really punishing them. Beyond the expensive tuition.” He threw up his hands. “Well, at least they’ve got a good journalism program.”

“And an excellent liberal arts curriculum,” Sophie added.

“And beautiful big-city girls who talk to themselves about Ned Flanders.”

“Right. I read about them in the catalog,” Sophie said, a little flustered by the beautiful comment. Also by the fact that they’d reached her dorm. “This is me.”

Russell took her hand. It was warm. “Ready to get your Hanukkah on?”

“Okily dokily,” Sophie said.

* * *

The suite was empty. Kaitlynn, Madison, and Cheryl had already left for the holidays, though they’d littered the suite with holiday cheer. Being in here alone with Russell, Sophie was suddenly knee-shakingly nervous, so she started talking in the same rapid-fire bap-bap-bap as Madison’s blinking lights. “And here is our fake tree, threaded with the traditional offerings of popcorn and candy canes. And you’ll notice the tinsel everywhere, not sure what that symbolizes, and that Santa balloon is made out of vintage Mylar. And if you breathe deep, you’ll catch a whiff of pine-scented potpourri. Welcome to the land where Christmas threw up.”

She was trying to carry on the joke of the Rudolph sweaters. But maybe it was a testament to how far they’d come tonight that the joke fell flat.

“Show me where you live,” Russell said softly.

Sophie’s quarter of the suite was like that thing on Sesame Street: One of these things is not like the other. No posters or corkboards with friendship collages. On her bookshelf she had a framed shot of Zora, an old shot of Luba looking glamorous and kind of mean, and a picture of her and her mother on a gondola in Venice. They’d had the same gondolier a bunch of times and he’d taken to calling her Sophia, crooning a song in Italian to her.

Russell was looking at the picture. “That was when my mom was in the Venice Biennale, a really big art show,” Sophie explained. Growing up, there’d been so many times she’d wished her mom could be a lawyer or a banker or a producer, the kind of jobs some of her friends’ parents had. But when her mother had been invited to show at the prestigious Biennale, and Luba had sold a ring so Sophie could accompany her, she’d been so proud of her mother, the artist. Glad that she’d stuck to her guns. It didn’t hurt that the trip had been magical: the gondola rides, the tiny zigzag of canals and alleys, the packed art galleries, and more than any of that, the feeling of some kind of portal of possibility opening. She hadn’t felt that way in a long time. She was feeling that way tonight.

“What kind of art does your mom make?” Russell asked.

“Sculptures. Though not the traditional kind with clay or marble. She works in abstract forms.” She reached to her top shelf and pulled down a small cube, all tangled wires and glass fragments. “Most of her work is on a much larger scale,” Sophie explained. “Like one piece could fill this room. Alas, my roommate Cheryl said she needed a bed so we couldn’t keep one here.”

For a second, she imagined Cheryl’s horrified expression if she had brought one of her mother’s larger, stranger installations. But then she remembered that Cheryl had seemed to admire her mom’s smaller piece. She’d held it a long time the first time she’d seen it, much as Russell was doing now. “Your mom makes sculptures,” she’d said. “My mom organizes bake sales.” Sophie had taken it as a veiled big-city comment, yet another sign of her otherness, but only now did she wonder if perhaps she hadn’t missed Cheryl’s droll brand of sarcasm.

Russell turned the piece in his hand, seeing how the light played into the angles. “My grandmother used to make these things … not sure if you’d call them sculptures or what, out of wood and sea grass. On Saint Vincent. Ever heard of it?”

“It’s an island in the Caribbean, right?” Sophie said.

“Yeah. It’s where my mom’s from. She came to the States for college, met my dad, and never went back. I used to go spend summers on the island with my grandmother. In this little house, painted in island colors, my grandma said, and there were always cousins running around, chickens and goats, too.”

Russell was smiling at the memory. Sophie smiled along with him.

“Then my father started sending me to camp during the summers: tennis camp, sailing camp, golf camp. We only go to Saint Vincent for vacation now, every year for Christmas. Last few years, we’ve stayed at a fancy resort, like tourists. And people treat us different. Like tourists. Even my own people.” He set down the sculpture, his expression wistful and yearning. “Except for my grandmother.”

Sophie closed her eyes. She could picture his grandmother, a beautiful lined face, hands tough with years of solid work, a stern manner that masked a deep ferocious love. After a bit, the image of his grandmother merged with Luba, who she pictured last year, broom in hand, swatting the smoke alarm after it went haywire from all the latke frying. Instead of pushing the memory away, she let it wash over. She was surprised to find that it didn’t burn. She could hold on to it. Then she opened her eyes. “Is your grandmother still alive?” she asked.

“Yeah.” Russell smiled.

“Are you going to see her?” It suddenly felt very important to her that he was.

“Flying down Sunday,” he said. “Looking forward to it.” He paused. “And dreading it. You know? Holiday stuff.”

“It’ll be okay,” she told him, but the words ricocheted back to her. It’ll be okay. That’s what people had been telling Sophie for a while now. After Luba died. It would be okay; time heals. After she started college. It would be okay; leaving home is an adjustment. Sophie hadn’t believed it. You can’t undo loss. You can’t unmake a mistake.

But now she was wondering if a garden of memories might not grow over the hole of losing Luba. And if college wasn’t a little like that first swim every summer—no matter how much Sophie looked forward to it, she still had to get used to the chilly water. Maybe anywhere Sophie had gone this year would’ve felt like a Bumfuckville.

Because this Bumfuckville had diners dropped from Oz. It had wingmen who had her back in poetry class. It had people like Cheryl, who, come to think of it, was pretty big-citily sarcastic herself. And it had guys like Russell.

What if the mistake wasn’t coming here, but being blind to any of that?

What the Hell Have You Done, Sophie Roth? she thought to herself for the umpteenth time. But it felt different now. If she’d made a mistake, there was time to fix it. And more than that, she was looking forward to fixing it.

* * *

They unplugged all the Christmas lights and laid the candles out in a vaguely menorah-like shape on the ground. Sophie found Luba’s menorah and put it out, too. They lit the candles. Where there was darkness, now, a warm glow of light.

“Normally you’d say a prayer in Hebrew,” Sophie said. “But I kind of think we’re doing our own thing, right? So I’m going to offer my thanks to that dumb caroling concert tonight.”

“Okay then,” Russell said. “I offer mine to reindeer sweaters.”

Sophie chuckled. “To cars with butt warmers.”

“And butts in butt warmers.”

“To hash browns,” Sophie said.

“Don’t forget pie.”

“Pie with cheese.”

Russell pulled Sophie into his lap. He was tall and she could sit in the fold of his legs, her own legs crossed under her.

“To perfect fits,” Russell murmured.

“And imperfect fits,” Sophie said.

Sophie reached up to touch Russell’s lips, and he grasped her fingers, kissing them, one by one: thumb, index, middle, ring, pinky, and back again.

“To Ned Flanders,” Russell said.

“Oh, yes, a thousand times to Ned Flanders. We should devote the holiday to him,” Sophie said.

Russell lifted up her hair and kissed her on the bony ridge of her neck. She shivered. “To the Rolling Stones,” he murmured. At that moment, not even Mick Jagger could’ve sounded sexier.

“And not always getting what you want,” Sophie said.

“But sometimes getting what you need,” Russell said.

She kissed his lips then. They tasted of apples and cheese, of the revelation of things you never imagined going so well together. She tasted meting ice cream, too, melting defenses, herself melting into Russell.

She kissed him, not knowing if the kiss would go on for a minute, an hour, the whole night. She kissed him not knowing what would happen next semester, next year. But at the moment, none of that seemed to matter. The kiss was what mattered. Not just the kiss, but what the kiss said. What it unlocked. What the night unlocked. What they had unlocked.

Tomorrow would be different. Sophie understood this.

There really was no such thing as a minor miracle.

The whole mess started when I lit the church on fire.

To be precise, I didn’t strike a match, and it wasn’t the church proper, but the barn beside it. The one that Main Street Methodist used to store all the equipment for the annual Christmas pageant. Well, the barn they used to use.

Put this on your list of things to know: the combination of tinsel, baby angel wings, and manger hay burns like weed at a Miley Cyrus concert.

My questionable reputation was established in the first grade. Vaughn Hatcher, the boy who covered the class rabbit with paste and a liberal coat of glitter and set him loose in the faculty lounge. It turns out, teachers think of glitter as the herpes of the craft world—impossible to contain or exterminate. Hippity Hop was sent to a petting zoo, and I was sent to the principal’s office. But it was too late. I’d already experienced the hijinks that could ensue when my creativity was put to good use. I was hooked.

I was the guy who taught the other kids how to egg houses, roll yards, and glue mailboxes shut. And the older I got, the more elaborate my pranks became. In middle school, I filled the clinic with Styrofoam peanuts. Last year, my junior year of high school, I decorated the town Christmas tree with neon thong underwear.

My list of achievements is quite impressive, if I do say so myself.

My failures equal one.

If I could justify casting off blame, it would belong to Shelby Baron. Shelby is a boy, by the way, and before I was kicked out of organized sports, he was the first-string quarterback. I was third. In basketball, he was starting center, and I cleaned up spilled Gatorade behind the bench. All of that, and he dated Gracie Robinson. He’s just always been better than me, so therefore I don’t like him. At least he’s not better looking. He’s Beefy Viking. I’m Tall, Dark, and Inappropriate.

On the day of the incident, I drove by the church and noticed that Shelby happened to park his Mini Cooper—seriously, a dude named Shelby who drives a Mini Cooper—underneath a tree. Said tree had a large flock of pigeons roosting on its branches, and there I was with a glove compartment filled with fireworks. I saw an opportunity, I predicted an outcome, and I had to see how it would all go down.

A lot of bird shit went down.

And, thanks to a wayward spark, I set the church on fire.

For the first time in my life, I was in real trouble. The juvenile system kind of trouble. But then something even more unexpected occurred—the pastor of Main Street Methodist swooped in and made a deal with the authorities. I was given a choice. If I’d agree to give up my Christmas break and help the church reboot the pageant, the incident would be expunged from my record.

For forty hours of community service.

I’d mowed a zillion lawns to save up for a winter-break trip to Miami. If I took the deal, I’d have to cancel it. No beaches. No nightlife. No bikinis. The most frustrating part was that I wouldn’t be able to get out of celebrating Christmas with my family.

All two of us.

But my alternative was possible probation or worse. I had the grades to get into my top college choices, but way too many admissions counselors were concerned about my reputation, and I was concerned about getting any letters of recommendation. Setting a church on fire is the kind of news that gets around. College would get me out of this town. Away from my house. Away from my reputation. The judge said I had a choice, but it wasn’t a real choice.

It had to be the pageant.

* * *

I couldn’t stop staring at Gracie Robinson’s pregnant belly. Well, not hers, exactly. Mary, mother of God’s.

Gracie has dark hair, innocent blue eyes, and skin like butter. She’s not yellow. I’m just sure if I ever got my hands on her skin, it would be soft. Not that I was planning on touching her or anything. Her father was the pastor of Main Street Methodist—the same pastor who was the reason why I was here, at the Rebel Yell, two days before Christmas.

The Rebel Yell was a dinner theater show that served fried chicken and beer in feed buckets. It featured a rodeo complete with clowns, tricks, and stunts, as well as rousing musical numbers. The theme pitted the Union against the Confederacy. Patrons picked sides and rooted for their favorite team—basically reducing the Civil War to a football rivalry. I hated generalizations about the South, but the Rebel Yell did make me embarrassed for my home state of Tennessee.

Though the church wouldn’t be sharing a venue with these carpetbaggers in the first place if I hadn’t destroyed their barn.

Twenty-nine hours down. Three pageant performances to execute. Opening night—tonight—and two tomorrow, for Christmas Eve. Eleven more hours, and I would be free from carrying wood, painting sets, sweeping floors, and climbing on catwalks to replace burned-out spotlights. The opening-night curtain would go up soon.

Yet somehow I’d found time to kill, just so I could be near Gracie. She’d always been nice to me—especially nice—but not the kind of nice that makes you wonder what percentage is actually pity. Since I started my community service, I’ve had exactly seven encounters with her. Not that I was counting. I caught her watching me a lot, but it was always while I was in the act of watching her, or while her boyfriend was around, so I tried not to obsess about it too much.

Her boyfriend wasn’t around right now.

Even though I’d looked for opportunities to talk to her, when she’d sat down beside me on a bale of hay, my mind had gone completely blank. I believe that saying nothing at all is better than saying something stupid, so I waited for her to start the conversation.

And waited.

And waited.

I’d been fidgeting with a tangled string of fairy lights and giving her belly the side eye for at least five minutes when she reached into her fuzzy purple robe, pulled out a watermelon-shaped piece of foam, and handed it over. “Please,” she said. “Inspect my womb.”

“It’s … nice. Plushy.” I gave it a squeeze and handed it back to her. I wasn’t up on faux-womb etiquette. I couldn’t even believe she’d said the word womb.

“Thanks to you, I got upgraded to cooling-gel memory foam. I can’t wait to see the rest of my costume.” She smoothed down the lapels of her bathrobe. “Assuming they get it made in time.”

I glanced around. Moms and dads were frantically putting the final touches on costumes that were replacing the ones that I’d turned to ashes. From what I could gather, robes and halos weren’t too difficult, but angel wings were a real pain in the ass. Possibly because of the glitter, but I didn’t offer up the herpes analogy. ’Cause you know. Church.

“I’m sorry.” I stared at the lights in my hands. The past week had been enlightening. Main Street Methodist had been presenting the nativity play for twenty years, and I’d wrecked it in one minute. “I keep waiting for the thunderbolt.”

“Stop looking over your shoulder. I didn’t say that to make you feel bad.” Gracie touched my knee for a split second before pulling away and tucking her hand into her robe pocket. “If my dad’s forgiven you, the Lord certainly has.”

I stared at my knee. “If the Lord and I started talking forgiveness, I’d be in a confessional for the rest of my life.”

She grinned. “Methodists don’t have confessionals.”

“Your father did more than forgive me,” I blurted out. “He kept me from going to jail. On Christmas.”

So, so awkward.

“Good thing, right? I don’t know if Santa visits juvie.”

“He wouldn’t come for me anyway. I’m on the naughty list.”

She should have been furious with me. Her acceptance rendered me as impotent as a vice president.

Gracie Robinson was simply nice.

Her reputation was the exact opposite of mine. She was captain of the safety patrol in elementary school, a student council rep in middle school, and, most recently, homecoming queen. She was currently in line for valedictorian of our senior class. She always had an extra pencil, and it was always sharp. Girls like that and guys like me don’t mix. Except when there’s a pending court order.

“It’s too bad we couldn’t get the barn repaired in time,” she said. “We tried.”

A pang of guilt, somewhere below my left rib. Maybe I could work in some public self-flagellation. I doubted it would help. I gestured to the confederate flag and the mini-cannon, which were shoved into a corner. “How exactly did you guys end up … here?”

I didn’t say Rebel Yell, because I couldn’t without wincing at the Civil War–as-entertainment reference.

Gracie pursed her lips. “We ended up here thanks to Richard Baron.”

Father of Shelby.

“He owns this franchise,” she said, not meeting my eyes.

Right. Of course he did. He bought his son a Mini Cooper. Obviously, sound judgment climbed high in that family tree.

She continued, “When we figured out we wouldn’t get things running in time, he offered us the venue for the two nights of the pageant. It’s the only place around here that’s big enough.”

“I’d say.” It had stadium seating and a huge, dirt-floor arena.

“Even so, claiming our own territory has been hard.” She shook her head. “But I guess you’d know about that.”

The job parameters of my community service ran the gamut. I’d done everything from helping the church move in the remaining props that I hadn’t set ablaze to serving as a stagehand for the actual production. Sorting out what belonged to whom involved pawing through an eclectic mix of Confederate memorabilia, oversized scrolls, and shepherd’s staffs. I still didn’t know if the trumpets belonged to the Civil War buglers or a heavenly host of angels.

“I’m surprised your father didn’t cancel it,” I said.

“It would’ve been easier, but this is the pageant’s twentieth anniversary. So many people were looking forward to it that Dad didn’t feel like he could turn down Mr. Baron, especially after he offered to pay for all the new materials we needed.”

Put another jewel in the Baron family crown. “Why did he offer?”

“Shelby is playing Joseph.”

“Gotcha.”

Just then, Gracie’s father rushed to the center of the stage, holding a clipboard and an enormous cup of coffee. He looked too young to head up a congregation of five hundred people. Like, boy-reporter young. Gracie shared his dark hair but not his eyes. They looked older than the rest of him.

He waved to get the attention of the people arranging the set. “Okay, let’s finish blocking these scenes so we can do a run through. I’m sorry, but that horse—when it’s replaced by a donkey—will have to take a left, behind the Wise Men, after they approach the Holy Family. Can you move that bale of hay to make it easier? Donkeys don’t jump.”

As adept as I am at predicting outcomes, I had to ask the obvious question. “What happens if that horse poops?”

As if it had been cued, the horse lifted his tail and took his evening constitutional.

“Wow,” Gracie said.

Pastor Robinson’s coffee sloshed onto the ground as he tucked the clipboard under one arm. I waited for the anger—for him to yell at someone to clean it up, to throw the clipboard, or to slam down his coffee cup. I’d never seen him show anger, but that’s what would happen if someone screwed with my dad when he was conducting business.

I heard Pastor Robinson’s reaction before I saw it. It didn’t register because it was illogical, to me at least. When he lifted his face, it was wet with tears.

A horse dropped a dump in the middle of his rehearsal, and the man was laughing.

“Not … what I expected,” I said. Humor wasn’t a typical emotion at my house even when my dad lived with us. Especially when he lived with us.

“If you don’t do bathroom humor, we can’t be friends.” She elbowed me in the side. When I didn’t respond, she said, “It’s funny, so he’s laughing. People do, you know.” Like she knew what I was thinking. Like she understood the differences in the ways we were raised.

Pastor Robinson’s hand rested on his shaking, Christmas-plaid-covered stomach. His wedding ring shone on his finger. It surprised me. Gracie’s mom had died when we were in the second grade.

“Vaughn?” She touched the top of my hand. “You can laugh, too.”

“Right.”

I pulled away and grabbed a shovel.

* * *

My family didn’t react to calamity with laughter.

My dad left when I was eight, and my mom never recovered. I’d tried to convince myself that it wasn’t my fault he left, but I never succeeded. I was hell at eight, in trouble all the time, and I’d always wondered what kind of strain my behavior put on their marriage. I had a distinct feeling that my dad didn’t like me, but he’d always been the one to handle the teacher’s conferences and suspensions. He made sure I had food and money, but that’s where penance for leaving his family stopped.

On the medication wagon, my mom could handle things like balanced meals and clean clothes. When she was down, she could barely take care of herself, much less her kid, and when she was up, she was a lightning strike—beautiful and unpredictable. I worked hard to keep her condition private, which is not a thing a kid should have to do. Fodder for country ballads, but also the reality of my life.

Shame leads to secrets, and secrets lead to lies, and lies ruin everything. Especially friendships. No kid wants to explain that his mom can’t bring snacks to class because she ran out of Xanax before the pharmacy would refill the prescription. Other parents stop inviting you to birthday parties, because you don’t reciprocate. No one asks you to join sports teams, because you never meet the registration deadlines, and if you do, no one ever remembers to pay your league fees. Soon enough, people forget you altogether.